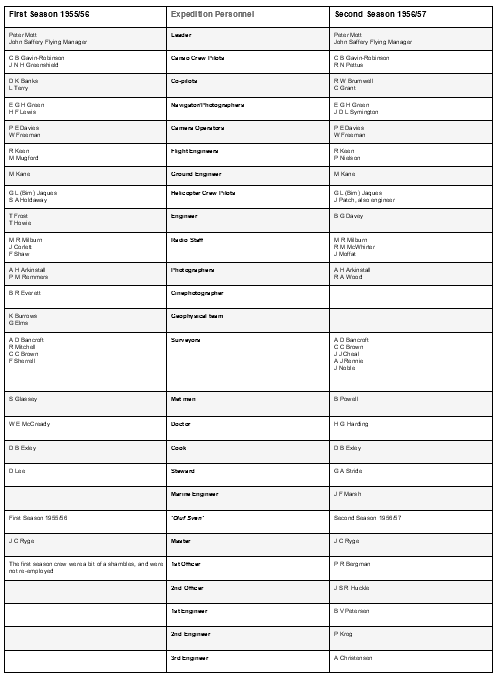

FIDASE Canso CF – IJJ (Jig Jig) flying over Graham Land (Copyright Aerofilms Ltd 1986)

The Falkland Islands and Dependencies Aerial Survey Expedition 1955 – 57 (FIDASE) – Richard Barrett

In July 1945 Peter Mott, who had spent the war years with the Indian Military Survey, wrote to Brian Roberts (formerly of BGLE) at the Foreign Office Research Department with a proposal for an air survey of the Antarctic Peninsula. Wheels turned very slowly and Peter was recruited into the Colonial Survey department of Brigadier Hotine, but instead of developing the Antarctic project he was instructed to go to Ghana. Declining this offer Peter joined Hunting Aerosurveys Ltd as Chief Surveyor.

The political situation in Antarctica at the time, with competing territorial claims by Britain, Argentina and Chile had resulted in Operation Tabarin and subsequently FIDS but by the 1950s the Foreign Office was of the opinion that more had to be done to maintain the UK claim to sovereignty and an aerial survey would reinforce the claim. Political wrangling between the Foreign Office, the Colonial Office and the Directorate of Colonial Surveys (DCS) delayed the project further. Huntings and Faireys were the two leading survey companies of the day and both were invited to tender in 1952. The contract was awarded to Huntings and signed in May 1955.

Hunting Aerosurveys was part of the much larger Hunting Group which had international shipping and aircraft operations. Their Canadian subsidiary had experience of aerial survey in the high Arctic using Canso Flying boats which was a Canadian amphibious version of the Catalina seaplane. The Canso was also equipped with wheels enabling them to be brought ashore, to keep them safe from floating ice and for ease of servicing and refuelling. The plan was to set up a flying base at Deception Island which is accessible by regular shipping in the summer months, frequently has ice-free water in summer, and with an accessible beach. The Canso was a slow aircraft (120 knots) and limited ceiling (13,500feet) but had a range of 2000 miles, was of rugged construction and proven reliability.

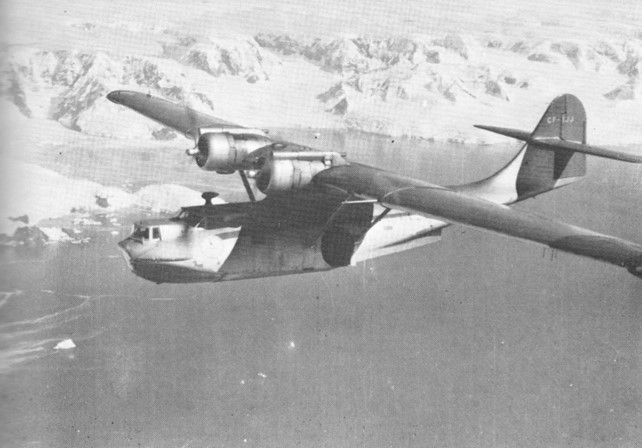

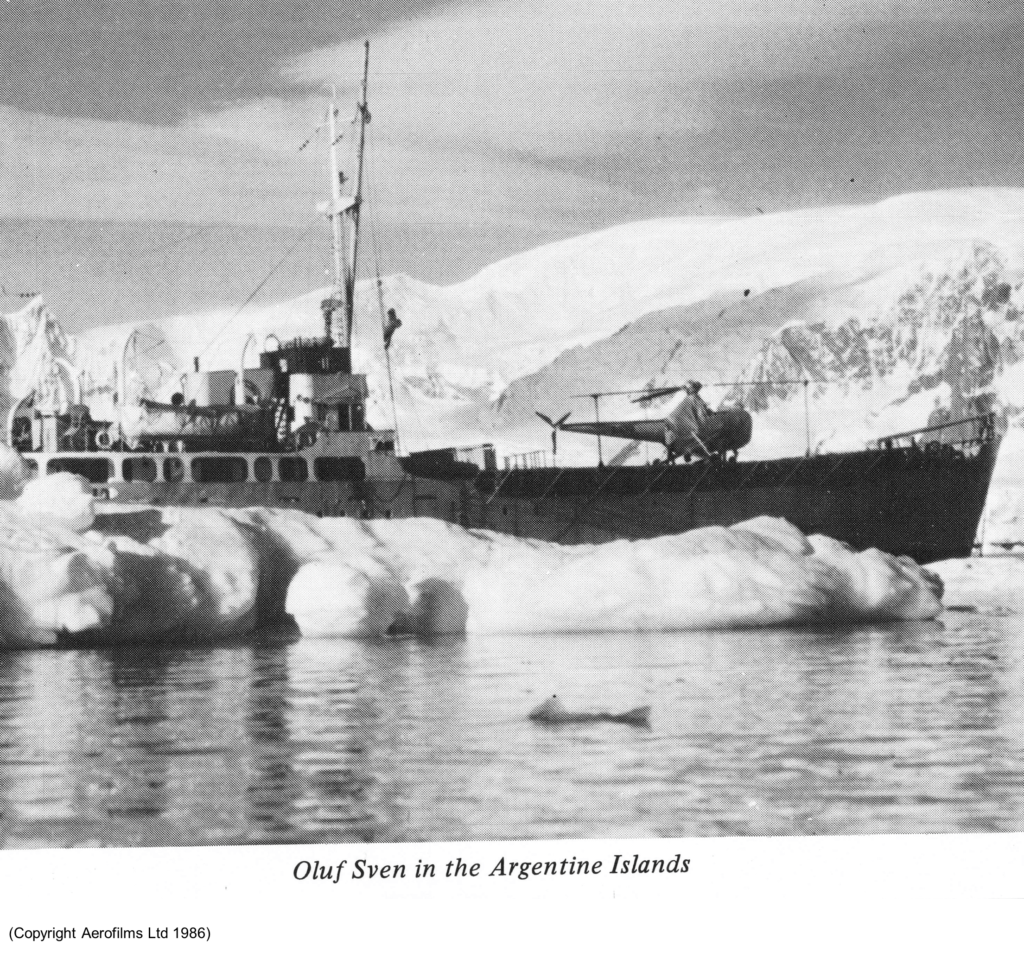

The expedition was estimated to require 60,000 gallons of aircraft fuel which made the choice of ship vital, the Hunting Group chartered the ‘Oluf Sven’. It was a 950 ton freighter which was converted to hold the fuel, act as aircraft carrier for helicopters, and be an expedition ship for 22 personnel plus crew. It also had to have sufficient space for the expedition stores including 2 helicopters, spare engines for the Canso and the expedition hut, food etc etc. The ship was modified by removing the foremast and creating a temporary flight deck over the forward hold, steel bulkheads in the tween decks to contain the fuel. Provision for very basic passenger accommodation and a mess hall was constructed in the aft hold.

After discharging cargo and setting up the flying base at Deception the ship would be used to fly off helicopters with the surveyors to establish the ground control points. Colin Brown formerly FIDS surveyor at Stonington 1948 – 49 joined the team.

After five months of frantic efforts the ship left London on 22 October 1955, met up with the ‘RRS Biscoe’ in Monte, spent five days in Port Stanley and arrived at Deception on 3 December with mail for the waiting FIDS. Then began the familiar routine of all hands turning to, unloading the cargo, building the hut (Hunting Lodge) and rolling the fuel drums.

The Canso aircraft left Canada on 26 November flying via Nassau, Trinidad, Belem, Salvador, Rio de Janeiro, Montevideo and Port Stanley. They had a difficult passage with tropical storms so severe that it took the paint off the fuselage and met headwinds of 96mph.

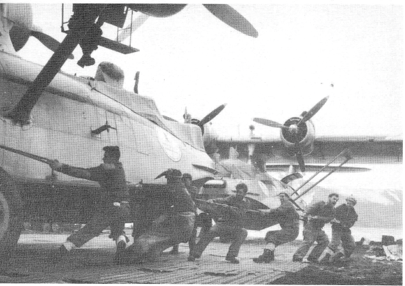

The 800 mile crossing to Deception was made on 10 January 1956 after 6 weeks and 70 hrs of flying. The base staff had constructed a slipway of expanded metal sheets, 220 feet long and 44 feet wide and used 5000 bricks salvaged from the whaling station. The radar approach landing system failed to be effective with a beacon at base, and in the following season 2 miles of cable were laid to erect a beacon at the Bellows.

The surveyors worked in the traditional way, measuring a baseline on the beach, fixing the position by astronomical observations and commencing a triangulation scheme.

The first flying day was 6 February 1956 with both aircraft in the air by 8am, flying strips of overlapping vertical photographs over Smith and Trinity Islands and the mainland. The helicopter were also now serviceable and began ferrying surveyors to their observation stations. The survey teams now became mobile, flying off from the ‘Oluf Sven’, although maintaining the Sikorsky S51 on the open flight deck was not ideal. Survey markers were oil drums bolted together, carried beneath the helicopter and dropped on summits.

On 10 March both Canso aircraft assisted in the search for 2 Argentinians adrift in a dinghy off Hope Bay without success. Heavy gales on 13 March saw the aircraft damaged by high winds and the helicopter badly iced up. The survey marker on Mount Kirkwood, consisting of 9 oil drums bolted together, was blown away but the surveyors observed angles to Mount Francais on Anvers Island 120 miles away.

They took the ship south for a reconnaissance of possible flying bases for 1957. At Port Lockroy FIDS base leader Alan Carroll was ex RAF and confirmed this was no place for a Canso. Aided by the ‘RRS John Biscoe’ they travelled south to the Argentine Islands in the knowledge that BGLE had used a float plane there. However the large amount of ice confirmed that this would be unsuitable for the Canso. On leaving and getting lost amongst the many islands they were assisted by ‘RRS Shackleton’ and Captain Ryge was relieved to reach the open sea and get some sleep after several days and nights continuously on the bridge. On 24 March they reached their furthest south at the north end of Adelaide Island. The helicopter paid a courtesy call to Detaille Island which was under construction with the FIDS living in tents.

They returned to Deception where the two Cansos had already departed. The helicopters and flight deck were dismantled and placed in the hold. The base was closed for the winter and the expedition sailed on 5 April 1956.

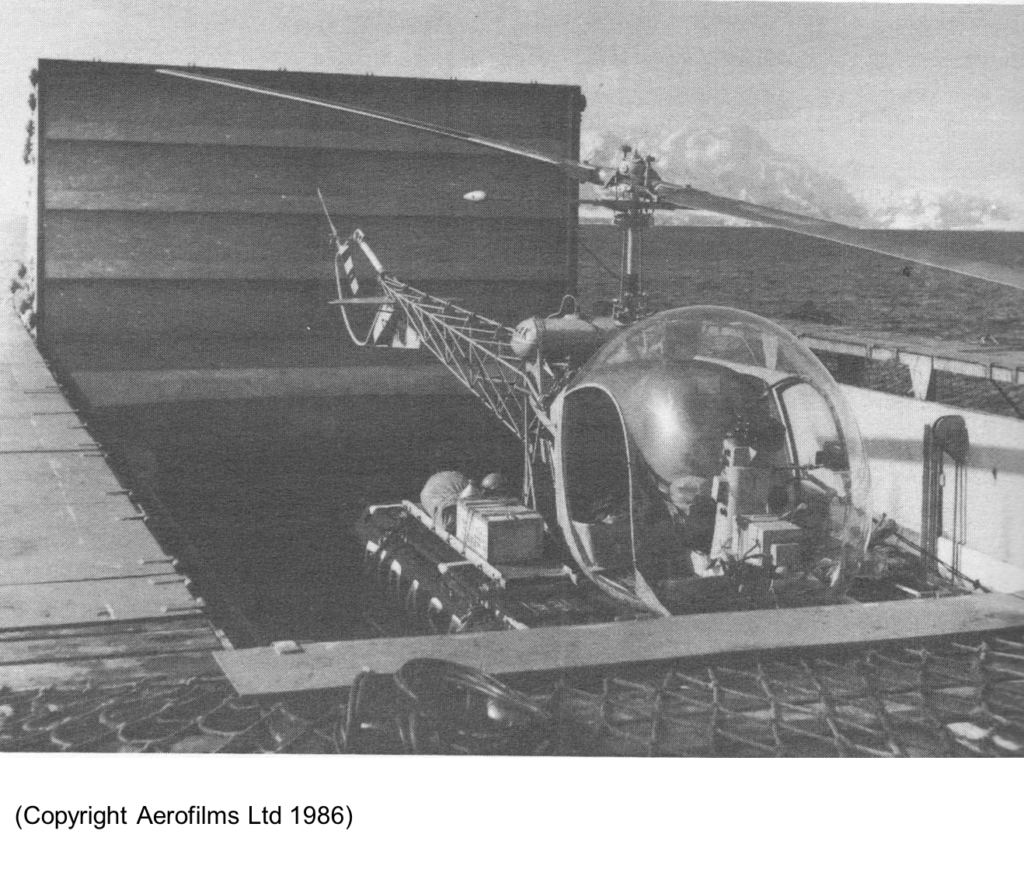

They arrived home with rather a disappointing total of work achieved and a mass of recommendations for the second season. The 1955 helicopter arrangement, keeping the helicopter on the temporary flight deck, meant that the second machine was kept for emergency and unused. A McGregor hatch for the hold and a lift for the helicopter would allow the helicopter to be kept and serviced below deck but only one helicopter was budgeted for the second season. The helicopter was changed from the Sikorsky to a Bell 47D with a bubble screen giving much better visibility and floats giving better safety over water.

For the 1956-7 season John Huckle, ex FIDS base leader Deception, ex harbour master at Port Stanley, ex Beaver pilot for FIGAS, joined the expedition as second officer on ‘Oluf Sven’ which sailed from Harwich on 20 October. The Cansos meanwhile had been refitted in Toronto and departed on 23 September arriving at Port Stanley on 15 October. In the five weeks before the arrival of ‘Oluf Sven’ the Cansos flew the whole of the Falkland Islands covering the 4,600 square miles with vertical photography. It took the entire floor of Port Stanley town hall to lay out all the photographs to check overlapping coverage of all the islands.

( In early 1982 I was working at Huntings and we received an urgent request from the Ministry of Defence for all the maps and photographs you hold covering the Falkland Islands. “What a coincidence we’ve just completed a similar order from someone in South America”. Richard Barrett 2022)

‘Oluf Sven’ reached Deception on 26 November to be greeted by the FIDS who had thoughtfully started the generators and lit the Esse cooker ensuring a warm welcome. In 4 days the base was operational and they were able to radio Port Stanley to call down the aircraft teams. After weather delays they eventually arrived on 9 December. On the same day the ‘Oluf Sven’ set off for Tower Island, the new McGregor hatch was concertina opened and the warmed up helicopter rose to the deck on the lift and made landings on Tower Island, Cape Kater and Cape Roquemaurel.

John Cheal and Jim Rennie, both ex FIDS surveyors, had joined the company and John Noble was on secondment from FIDS. The team of surveyors was now 6 strong including the leader,Peter Mott, Tony Bancroft and Colin Brown. The priority was to establish control on the Peninsula mainland, offshore islands and the connection to the South Shetlands.

On the first day of the survey operation the Bell 47D crash landed in white out conditions on Tower Island without injury to the pilot Bim Jacques or surveyor John Noble. Bim had already landed twice on the island but on the third trip he suddenly lost visibility and found he was flying backwards in a strong downdraft.

A rescue party was landed by the ship’s lifeboat and the following day reached the site of the wreckage and recovered the personnel with all the equipment, and returned to Deception.

The decision, to only have one helicopter, was now seen to be painfully flawed. Brigadier Hotine DCS suggested continuing the survey using small boat landings and astro-fixes, failing some how to realise they were in 24 hour daylight.

The surveyors moved to King George Island. Helped by FIDS they began surveying using small boats and old school man-haul sledges. ‘Oluf Sven’ headed for Montevideo to collect a replacement helicopter which arrived on 4 January 1957, without any rotor blades and with the perspex bubble smashed, which took another two weeks to be replaced. The ship met the surveyors on King George Island and spent 2 days completing the survey.

At base on Deception additional material for the slipway now enabled two Cansos to come ashore under their own power and complete a taxying circuit and park two aircraft ready to launch. The first flying day was 14 December. Both aircraft were in the air for 7 hours completing 1,200 square miles of photography, more than the entire previous season. The base hut, Hunting Lodge, was positioned next to a meltwater stream which was essential for the 500 gallons of water necessary to process the film and produce contact prints. The contact prints were stapled together in long rolls to record the area covered.

Radio communications were vital for maintaining contact with the two aircraft and getting weather information from the FIDS bases. The FIDS equipment was rather old and ‘noisy’ and so FIDS moved their radio base from Deception to King George Island. Weather information came from Port Stanley, who had loaned to the expedition, meteorologist Brian Powell, to compile forecasts. The aircraft could not land on water with full fuel tanks and there was concern in the event of failing weather they would have to burn off fuel before landing.

A further 4 flying days before Christmas saw the photographic coverage increased to 5,000 square miles. Snow and gale force wind ensured that Christmas Day was not a flying day and could be fully enjoyed with Uruguayan turkeys and Monte plonk. An evening buffet with the FIDS invited went on till 1am but the pilots had already retired ready for the usual 5am call on Boxing Day. The aircraft were in the air by 7:30am, only returning when they had run out of film at 3:30pm. After refuelling and a quick meal the aircraft took off at 4:45pm for a further 2 hours flying. The photo lab technicians, all hands and passing FIDS were roped in to process film and produce contact prints overnight for another 3,000 square miles of coverage. The planes were off again at 7:30am returning in the afternoon with another 6 full magazines. Thankfully the weather closed in, as the processing lab had been running non stop for 72 hours, but a full 40% of the coverage was now complete.

A royal visit from Prince Philip on 3 January 1957 aboard ‘R Y Brittania’ with ‘HMS Protector’ brought some light relief during a period of bad weather. This ended on 9 January when the aircraft first crossed the Antarctic circle, then flying as far south as Adelaide Island. On the 11 January both aircraft were in the air flying south to the contract limit of 68 S, flying four parallel lines in good light even at 8pm. By the end of January five further sorties saw the contract coverage up to 70%. Flying became more difficult, the aircraft having to get airborne to see what the weather was like and trying to fill the gaps in the coverage. The last sorties were flown on 25 February over Clarence and Elephant Islands. In two months 40 sorties had been flown and 11,000 exposures made covering 35,000 square miles.

It was not until 26 January the the ‘Oluf Sven’ arrived back at Deception with the surveyors from King George Island and the new helicopter. Within 24 hours they were off again to try and salvage the survey season. Making the most of the occasional good weather and with the helicopter flying up to 40 sorties a day the survey progressed southwards amongst the spectacular scenery of the Antarctic Peninsula.

The aircraft departed Deception on 3 March but soon CF-IGJ returned with an engine noise. After a limited examination, as all the essential tools were on CF-IJJ and a test flight, the aircraft set off again on 6 March but with the problem unresolved. CF-IGJ arrived safely in Port Stanley where they had a spare engine, which was installed, departing for Canada on 26 March.

With the departure of the aircraft the ‘Oluf Sven’ went south again for one last attempt at some more survey. A set of contact prints were handed over to FIDS at Port Lockroy for use by surveyors and naval hydrographers in the area. They also left Peso, a mongrel puppy that had come aboard in Montevideo and had been kept as a pet. Very variable weather was maximised with the helicopter rapidly deployed to place surveyors then retrieve them when conditions worsened with the last day of survey 20 March. ‘HMS Protector’ had meanwhile recovered the wrecked Bell 47D from Tower Island.

‘Oluf Sven’ returned to Deception to close down the base and retrieve as much equipment as possible, including spare aircraft engines, the tractor and the $1,000,000 shelf of 113 tins of exposed aerial photo negatives. Getting underway on 30 March to finally leave Deception the surveyors found a discrepancy in an angle on Cobalescou Island and a final detour was made which allowed some of the team, who had spent the whole time on Deception, to finally get a look at some scenery. A last visit was made to King George Island to collect mail and give a set of contact prints to the FIDS there. The opportunity to visit Elephant Island was missed as the weather worsened and the ship headed north into a rising gale. After 36 hours of storm the wind abated and the ship resumed course and reached Port Stanley on 4 April.

There was talk of a third season, but there was no budget. In hindsight, a third season with reasonable weather could have completed the photography and survey ground control. If Huntings had been awarded the contract for photogrammetry and cartography, the Antarctic Peninsula north of 68 S could have been mapped by 1960.

Rarely can the success of an Antarctic expedition be judged, but FIDASE achieved;

• 100% Aerial Photography of the Falkland Islands;

• 80% Aerial Photography of the Antarctic Peninsula 62 S – 68 S

• 25% Survey Control of the Antarctic Peninsula 62 S – 68 S

I had the good fortune to visit Deception in 2001 and Hunting Lodge was still there but looking a bit sad. The meltwater stream which had been vital to the supply of fresh water had undermined the end of the hut and it looked in danger of collapse. There did not seem to be much other evidence of the FIDASE expedition apart from an explanatory plaque.

(Photos: Richard Barrett)

It is good to see that the FIDASE photography is still in use in current Antarctic research usually as a baseline for long term studies.

Details from:

- Topographical Survey and Mapping of British Antarctic Territory by Barbara McHugo

- Wings over Ice by Peter Mott

Richard Barrett – Surveyor Stonington 1974, Adelaide 1975

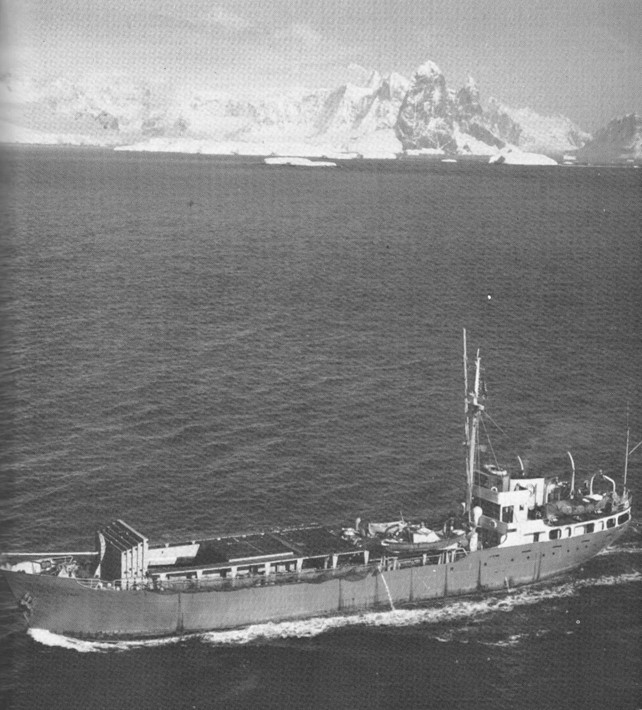

Crew List