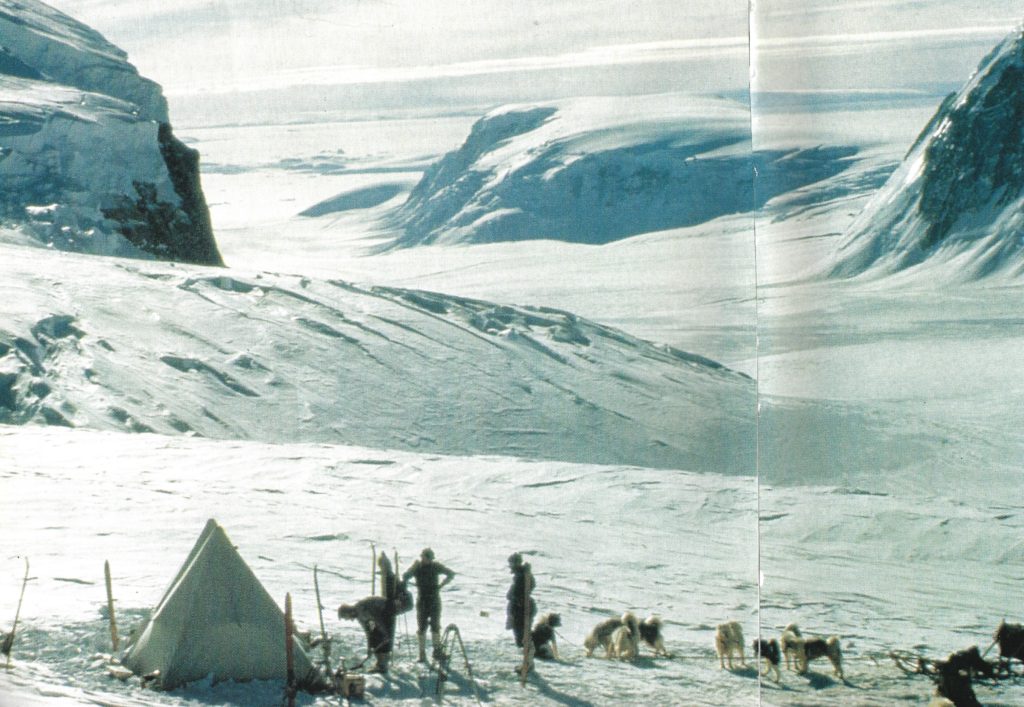

Header Photo: Ric Airey, 1979

History

Detaille Hut (Base W), Lallemand Fjord, Loubet Coast

Although not technically in Marguerite Bay, Detaille Island Hut was integral in the topo survey and geology of Marguerite Bay. It was occupied for three years and abandoned when in successive years the BAS ships were unable to get close enough to resupply for another winter.

Detaille Island hut was established in 1956 as a base used primarily for mapping, geology and meteorology as well as to contribute to the science programmes of the International Geophysical Year in 1957. Located in the Lallemand Fjord, off the Loubet Coast this small island (66°52’S, 66°48’W) south of the Antarctic Circle is in an area most commonly referred to as Crystal Sound.

The base has a brief and exciting history as a sledging base. Over three years the men and dog teams at Detaille covered distances of up to 4,000 miles, mapping the area for the first time. In 1959 it unexpectedly closed due to severe pack ice. At the first opportunity, with very little notice, the men abandoned the base sledging across the sea ice to reach the evacuating ship.

For the first two years of the base’s operation, unstable ice meant that field parties working on the peninsula were repeatedly cut off for long periods. However, in the winter freeze of 1958 solid sea ice formed which allowed safe sledging and made it the most productive year. The solid sea ice however caused other problems as when the relief ship arrived in the summer of 1959 with new personnel and fresh supplies it was unable to break through the ice despite assistance from two American icebreakers.

The base did not have enough coal and provisions for another winter and the ships were unable to unload essential provisions from the ice edge. Eventually, the master of the ship made the call to shut the base and with little time to spare the men secured the building against the elements, packed the minimum of their belongings and sledged across thirty miles of sea ice to reach the ship. Detaille operated for just three short years and in spite of the difficulties, much was achieved in terms of geological mapping and surveying of the surrounding areas.

Winters

1956

Detaille Base Commander – Tom Murphy

| Cooper, R.E. (Ray) | DEM |

| Miller, R. (Ron) | GA |

| Moore, D.P. (David) | Radio Operator |

| Murphy, T.L. (Tom) | BL, Surveyor |

| Orford, M.J.H. (Michael) | Surveyor |

| Salmon, E.M.P. ** (Eric) | Meteorologist |

| Thorne, J. (John) | Meteorologist |

| Wright, H.G. (Hedley) | Geologist |

** – Eric Salmon wintered as a Meteorologist at Signy (1950), Deception (1951), (Argentine Islands) (1954) and Detaille Island (1956). More about Eric here:

Topographic Survey

1956-7 Murphy and Orford

A new base was established at Detaille Island in February 1956. Before the sea ice formed a small triangulation scheme on the island was beaconed and observed and a detail map of the island performed at 1:2,400 scale. Sledge wheel and compass surveys where carried out along the mainland coast and eventualyl up onto the Avery Plateau at 1680m where they were able to link to work from Mason’s 1946 plateau survey and obtain a sun-fix.

1957

Base Commander – Angus Erskine

| Connochie, O.S. (Ossie) | Radio Operator |

| Erskine, A.B. (Angus) | BL, Surveyor |

| Goldring, D.C. (Denis) | Geologist |

| Madell, J.S. (James) | Surveyor |

| McDowell, W. (David/Bill) | Meteorologist |

| Oliver, F. (Frederick) | DEM |

| Scarffe, J.M. (Martyn) | GA |

| Smith, J.P. (John) | Meteorologist |

| Thorne, J. (John) | Meteorologist |

| Wyatt, H.T. (Henry) | MO, Physiologist |

Topographic Survey

1957-8 Erskine and Madell

Sledge wheel and compass surveys of glaciers into Darbel Bay and Lallemand Fjord and onto Avery Plateau, better weather allowed some star fixes to be observed. FIDASE photography became available and the survey work changed to systematic triangulation to provide control points for mapping. Angus Erskine and Jim Madell measured a baseline near base and reconnoitered a triangulation scheme from 66.5s along the coast and down Lallemand Fjord which was observed in the spring. When the sea ice was unsafe further work was done on the local map for the geologist and a 16 star astrofix observed.

Dogs, Theodolites and Crevasses – Angus Erskine

The decision was made in a London pub. Over a glass of ale, Johnnie Green, who I had known for seven years, persuaded me to apply to join FIDS. It was 1956 and he was the FIDS Operations Officer. I said I would, provided he promised to send me to a base where dogs were the main means of transport. Earlier in the 1950’s I had spent 3 years in Greenland driving my own team on the British North Greenland Expedition, having learnt the skill from the Greenland Eskimos and the lure of the snowy wastes was calling me again. And so it happened.

In February 1957 I jumped ashore from the RRS John Biscoe with 8 companions and a motley collection of dogs brought from other bases, at Detaille Island, known as “Base W”, in Lallemand fjord, where a brand new base had been built a year before. I had been appointed Base Leader and Surveyor. It was a small rocky island lying 8 miles off the mainland of the Antarctic Peninsula and I gazed at the heavily glaciated panorama of alpine mountains and glaciers with awe and excitement.

Foul Language – Angus Erskine

‘Seldom elsewhere have I heard such foul language as it is used by the dog driver. Whatever stories a driver may tell you, he never has 100% control over his team – only degrees of lack of control.’

All travel in Antarctica involves considerable danger. There is sea-ice to break through, crevasses to fall into, avalanches to be buried under, and blizzards to get lost in. The proper use of well trained dog teams provided a safety factor that made almost of the early exploration of the Continent possible — and where British field work was concerned, that meant dogs leading out in front.

Byway Glacier – Angus Erskine

There was a steep glacier which curved round a mountainous bluff so that the crevasses were numerous and large. The glacier descended into Darhel Bay, right on the Antarctic Circle on the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, and not far from Detaille Island. The surveying of Darhel Bay, with its ring of formidable peaks and glaciers, had been delayed for many years because only three out of the 20-odd jumbled glaciers looked like being even remotely negotiable, and the ice on the bay itself was highly unreliable. On this occasion, John Thorne and I managed to make a jolting descent from the spine of the Peninsula down what is now called Erskine Glacier, and met up with Dennis Goldsmith and Ossie Connochie on one of the islands in the bay where they had been cut off by open water. Then all four of us, with the two dog teams, found a route by Byway Glacier to the Plateau again, sledged south along it, and eventually returned to Detaille, keeping a running survey going on the way.

Throughout this hazardous journey, the dogs were sure-footed and steady, whether on glacier or sea-ice, and my lead dog, “Bodger”, led the whole way, obeying my steering orders with an accuracy which surprised even me.

Angus Erskine, BC – Detaille, 1957

Lallemand Fjord – Friday 7 February (off Base W) – Robin Perry

(Photo: Robin Perry)

So near and yet so far! We had been warned about the winds at Base W, and here we are at anchor only a hundred yards from Detaille Island on which the base is invitingly built, but unable to disembark because the southerly gale is too strong even for the Biscoe’s lifeboat. Going back to yesterday morning, we made good progress but snowclouds hid all the landmarks. Around teatime the snow stopped, the clouds broke and the ice became more broken.

There was a fine vista of distant mountains. We passed quite close to Detaille Island, but first had to make for the refuge hut on the mainland to the east, a site known as Johnston Point, because four members of the base who had been sledging on the mainland plateau had had their line of retreat cut when the ice broke up.

The four who had been living in the small hut for a couple of months or more were Angus Erskine, the Base Leader; Denis Goldring, geologist; John Thorne, meteorological observer; and ‘Ossie’ Connochie, radio operator. The four looked impressively wild and unkempt.

1958

Base Commander – Brian Foote

| Foote, B.L.H. (Brian) | BL, Surveyor |

| Goldring, D.C. (Denis) | Geologist |

| Graham, J.G. (John) | Medical Officer |

| Johnson, C.C. ( Colin) | Radio Operator |

| Oliver, F. (Frederick) | DEM |

| Perry, R.M. (Robin) | Meteorologist |

| Rothera, J.M. (John) | Surveyor |

| White, P.O. (Patrick) | Meteorologist |

| Young, J.W. (James) | Meteorologist |

Topographic Survey

1958-9 Foote and Rothera

John Rothera extended the triangulation into northern Adelaide Island and south to the work in Laubeuf Fjord and down the Lallemand Fjord to connect with the work in the Arrowsmith Peninsula.

Brian Foote extended the work northwards into Darbell Bay.

Further detailed survey work was done for the geologists and in March 1959 the base was closed. Unusually the winter sea ice had not gone out and the Fids had to sledge 48km across the sea ice to reach the RRS John Biscoe.

Seventy-eight Feet on a Walk in the Antarctic

Being an account of a very ordinary Sledge journey by three men and eighteen dogs

(Photo: Robin Perry)

The object of the journey was to place a depot of man and dog-food and paraffin on the Plateau at the top of the Murphy Glacier for use by the summer survey party. After two months of very bad weather we felt we were due for a change. Brian Foote had been out surveying in Darbel Bay for eight weeks with Paddy White in charge of ‘The Counties’, but during all that time there had been less than five days suitable for observations. The team required seal meat to fortify them before starting on the glacier trip so it was arranged that the three of us should depart for the ‘field hut’ at Johnston Point a couple of days after Brian and Paddy returned. There John would shoot and bring in as many seals as possible (there was a dearth of them around base) whilst Frank and I ferried the depot load up the steep hill behind the hut.

Relief by Icebreaker

The sea ice inside the Biscoe Islands never dispersed at all that summer. At the end of February the John Biscoe, with the help of the United States Coast Guard Cutter Northwind, placed themselves at the ice-edge in Matha Strait and sent in a tractor towing a large sledge. Since I was the only man going further south (to Marguerite Bay), only I left base then, on a sledge train behind the tractor, without any dogs. Base W would be relieved if possible when the ships returned, otherwise the men with still a second year to serve would be dispersed among bases further north. Likewise the dog teams would be farmed out.

Northwind had a helicopter (in fact two), a great asset for finding the best passage through the heavy pack-ice along the west coast of Adelaide Island. When the ships eventually reached the edge of the Marguerite Bay fast ice, the season was already advanced, and it was decreed that all exchange would be by air. The base at Stonington Island (Base E) was closed, and the personnel sledged up to Horseshoe Island (Base Y) to await evacuation.

(Photo: Robin Perry)

Thus it was that I was flown in aboard a helicopter to Base Y, and almost immediately the first of the homebound personnel were airlifted back to the ships. Among those who came up from Stonington was Nigel Proctor, a geologist, who had been at Trent College with me back in the late 1940s.

We had little time to say more than hello and goodbye. He had done his two years and was going home. The whole changeover was effected in five flights by the helicopters, and on 6 March we watched our last link with the outside world disappear over the low rocky hills to the west. The ships then followed the sun northward, though not without difficulty

There was no miracle. On 31 March it was decided that Base W would have to be abandoned. Men and dogs sledged out to join the ships. Frank Oliver’s team ‘The Komats’ included twins: black and white dogs called Porgy and Steve, notable in having mirror-image markings. In principle they were inseparable. We learnt by radio that, on the way out to the ships, Steve had escaped, and was not at all disposed to rejoin the team or even to continue with the party. In fact he set off back alone towards the now empty base, and had to be given up as lost.