The realisation that we were stuck at the Argentinian Base Belgrano 1, on the Filchner Ice Shelf dawned on us slowly. Hopes of rescue had faded over several weeks. However, stuck we were, and it looked as if it was going to be a long, cold winter. And so, it proved to be!

Arrival at Belgrano:

“We”, were three Fids; John (‘Youth’) Wright, a Halley G.A.; Phil Marsh, a Geologist (summer only or so he thought!) and me, Dog Holden, a Rothera G.A. and B.C.

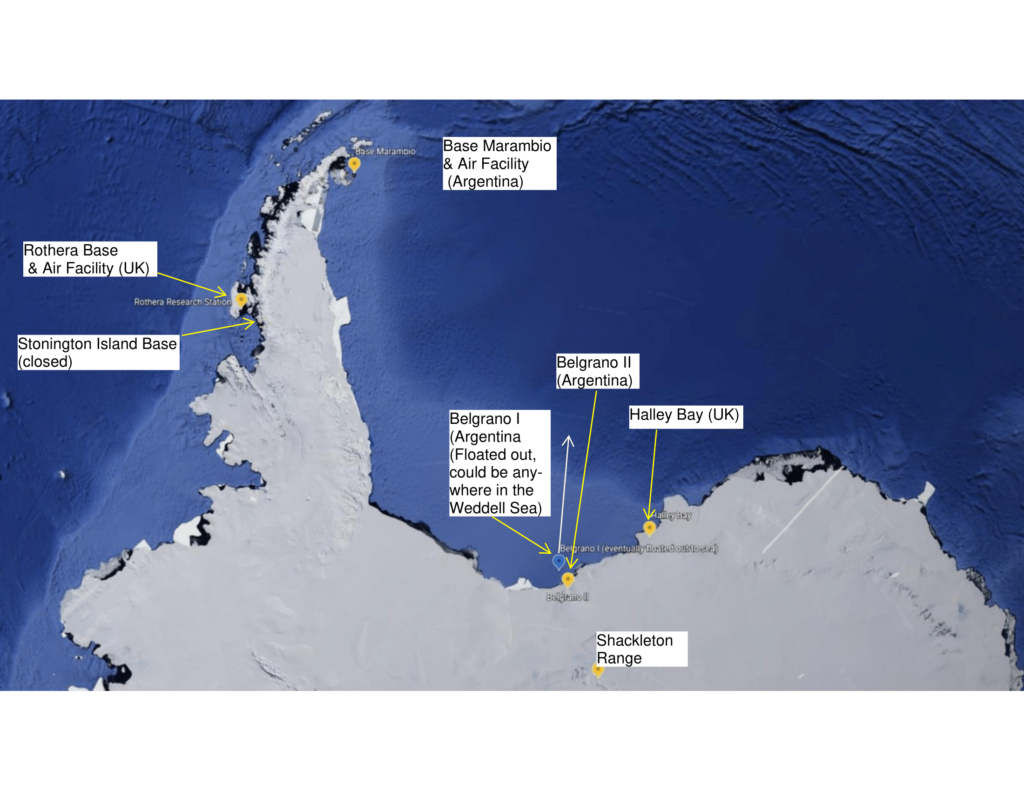

Youth had wintered at Halley in 1977 and prepared the gear for 2 x 2 geology sledging parties for the 1977/78 summer season in the Shackleton Mountains. I had been at Rothera winter 1977 (after wintering at Stonington Island and Adelaide Island bases in ’74 and ’75) and Phil Marsh, was flown into Rothera in Spring ’77 as was the Senior Geologist, Peter Clarkson.

Pete, Phil and I flew into the Shackletons from Rothera (via Belgrano) in November 1977 and Youth was flown in with the gear from Halley.

We all had a great field season in the Shackletons. Although colder, at 81°S, the weather there was much more stable than that of the Peninsula and there were a lot fewer crevasses too!

On 6th February 1978 we were flown out of the Shacks to Belgrano. The plane also brought in a party from the Pensacola Mountains, Les Sturgeon a Rothera Geophysicist/G.A., plus a couple of United States Antarctic Research Programme (U.S.A.R.P.) surveyors. Together with all our scientific results and sledging gear we were brought in from the field over a couple of days to consolidate and for plane refuelling before the long flights back over the Weddell Sea to Rothera. This was the reverse of the process that had put us into the Shackletons the previous November.

On arrival at Belgrano we were quickly launched into a huge party. Pete Clarkson had arrived there earlier in the day and informed the Argentinians that it was my 30th birthday, so the Argies had got out the bunting, the whistles, the beef and the booze. As all sledgers know, these parties are enjoyed after a long spell in the field. We thought that one or two more of those, then a flight back to Rothera for a few more would just about see us right. Little did we know that there would be many more to come at Belgrano and that we would still be there 9 months later!

Looking Around:

Although we had spent a couple of days at Belgrano on our outward journey at the start of the season, we now had a chance to explore the base more thoroughly. What a place! Giles Kershaw, the late, great BAS pilot had told us that it was in by far the “worst” condition of any base he had seen (a lot) in all his Antarctic experience. We could see what he had meant.

It had been built in 1955 a few miles west of Shackleton, the old Transantarctic Expedition (T.A.E.) 1955-57 base on the Filchner and was by 1978 less than half a mile or so back from the ice front. In order to present a low profile to the winds to minimise the drifting in and crushing of the huts a long trench had been dug in the snow and a line of huts set in it. At intervals along each side of these huts were set enormously thick pillars of Quebracho, a South American hardwood. Across the top of the pillars were placed old railway lines and then this was roofed in with chicken wire, plywood and canvas. This provided a gap of about 6 ft. above the aluminium roof of the huts.

No doubt this worked for a few years but as several generations of Halley Fids will testify, the snow wins in the end. Some things must stick up above the surface; masts, antennae, genny exhaust pipes, etc. Eventually the drift builds up from these. This and the movement and flex of the ice shelf meant that, by 1978, the Belgrano huts were 50ft down at floor level and very badly twisted and crushed. The columns and railway lines were split, burst and broken and had been pushed through the huts’ cladding of timber and aluminium and were poking through the walls and ceiling. Through the holes so formed, the relatively warm air from the base escaped, melted the surrounding ice and the melt water came in through the same holes, and promptly froze on the floor!

The interior was a gloomy optical illusion with no straight lines and crazily angled floors making walking difficult.

So, this was not too different from any old ice-shelf base of the period. Most of them though had been abandoned! Virtually everything else was in the same desperate state, the generators, wiring, heating, radio and scientific equipment, stoves, chimneys, etc. To cap it all, the whole place, and its inhabitants were as dirty black as coal miners at the end of a shift at the coal face! This was because the heating stoves were of a rudimentary drip-feed kerosene type which produced copious amounts of “lamp-black”.

Weather/Flight Problems/Contingency Plans:

Anyway, back to our arrival. Together with our pilot and Twin-Otter we settled down to a routine of regular radio scheds. with Rothera, our intended destination. Given the 1,200-mile, 9-hour flight, it was important to get the weather right on the whole route if possible, certainly at both ends. However, a pattern had set in whereby if we had good weather, Rothera would be bad or vice-versa, or both.

Whilst we were waiting, we paid a flying visit to Druzhnaya, a Soviet Union base about 45 miles west along the Filchner Ice Front. We had had quite a lot of contact with some of their field personnel whilst we had been in the Shacks during the summer. They had given us a brilliant meal in one of their large, felt covered Yurts, complete with pot-bellied stove that they used for base camp in the field. The vodka was stored outside at -25°c, which, so they assured us, was the perfect temperature for vodka. It tasted good to us!

The days passed and we were not getting the weather breaks. Pete Clarkson and I discussed the situation and agreed that if and when the chance arrived, he, Les Sturgeon plus the two USARP scientists, together with their Geoceiver hardware and data should go on the first flight. This would leave John, Phil and me to wait for another flight. As a contingency against the BAS plane not being able to return for us, we planned to ask the Soviets at Druzhnaya if they would take us out on their icebreaker. This was expected to relieve Druzhnaya in a few weeks’ time and would have to steam along the shore lead past Belgrano on its way to and from Druzhnaya.

When the Soviets paid a return visit to Belgrano by helicopter a couple of days later, we put this request formally to the Base Commander, via the East German Senior Geologist with whom we had worked in the Shacks. He spoke excellent English and there was no confusion or misunderstanding of the issue. It was not the most trivial request however since it would mean us being taken by ship all the way to the Canary Islands, the Soviets’ first stop after leaving Antarctica. The Cold War was still very much a reality so what we were asking was a major and sensitive favour. However, given the good relationship we had established with their field parties, the Soviet Base Commander, Dr. Mazurov, readily agreed, subject to the plan receiving the approval of the Arctic and Antarctic Institute in Leningrad. We further discussed the difficulty we had been experiencing in getting radio contact with Druzhnaya. Even though it was not far along the ice front, both bases’ antennae arrays faced north and were set up for long distance work, not short distance E-W, as it were.

This meant that it was unlikely that we would be able to let the Soviets know directly if we were still at Belgrano by the time of their relief. Dr. Mazurov understood and agreed that radio comms. between us had been poor. He told us that he would send a helicopter for us at relief time anyway; on “spec” as it were, even if they had not heard from us! If we had already left, no problem.

This was said, complete with translators in front of the Argentinian Base Commander and other personnel, as well as all the Fids and U.S. personnel present. There was no doubt in anybody’s mind that the plan was exactly as I have described it.

Eventually, the Twin Otter did get away with its first load for Rothera. It took it more than a week to get there! Bad weather en route forced it to land on Alexander Island and all 6 on board camped out until the weather cleared. It was thus looking very likely that we would have to call on the Soviets, so a request was put to Leningrad for permission, as agreed. At that time, BAS ship RRS Bransfield was relieving Rothera and on board was Dr. Ray Adie, then Deputy Director of BAS. Via his personal contacts at the Arctic and Antarctic Institute he quickly obtained this permission. Fortunately the Radio Op. at Rothera, Alan Cheshire, spoke fluent Russian and although he could not establish direct contact with Druzhnaya, he was in regular touch with the Soviet base Bellingshausen on King George VI Island, and it relayed on to Druzhnaya that we needed collecting and that official permission had been given.

Getting Worried:

Even allowing for this complex communications chain, there was no doubt in our minds that all the pieces of the plan were in place and all parties understood what the situation was. Thus when we finally had to give up trying to get the BAS plane back over for us, the button to activate the plan was pushed and the airwaves were humming as radio contact with Druzhnaya was attempted by all and sundry, us at Belgrano, Rothera, Halley and, we were led to understand, Bellingshausen Base. The latter assured us that the message had been received by Druzhnaya and we felt confident that all was well. We also had the assurance that, as arranged, the helicopter would call for us in any case. So, we waited!

A few days later, as I was out for a walk, I spotted the masts of the Russian icebreaker passing along the ice front, following the coastal lead, westward towards Druzhnaya. I gave John and Phil and our Argentinian colleagues the news that the relief of Druzhnaya was underway and felt confident that we would shortly be heading home way home.

Days passed and nobody arrived! Increasingly frantic attempts to contact Druzhnaya, the Russian icebreaker, Bellingshausen and even Leningrad all failed to produce a response. Suddenly the Soviets everywhere stopped answering our calls and went off the air completely. It was many days after my sighting that we heard (from Halley I think) that the icebreaker had gone without us and was well north in the Weddell Sea. They had abandoned us, the bastards!

We have never, to this day, received a decent explanation not to mention an apology, of why they let us down but there is absolutely no doubt that they knew our predicament and had agreed to pick us up. They broke their word or were ordered to!

Last Chance:

Meanwhile however, a last, desperate plan to get us out was being hatched by Dave Fletcher, then in his first season as Summer Operations Manager at Rothera. A Twin Otter belonging to Survair of Canada had been working out of Rothera during the summer and had been damaged by strong winds. It was decided to “winter” it at Rothera by virtually burying it in the snow. A spare tailplane would then be brought down for it the following season. In addition, one of the BAS Twin Otters had been badly damaged during take-off attempts at the end of the flying season. This plane was being dismantled for shipment home on RRS Bransfield.

Dave (Fletcher) came up with the sensible idea of fitting the Servair Twin Otter with the BAS plane’s tailplane and the resultant hybrid being flown to us by the Servair pilot. The Fids at Rothera spent a couple of days digging out the plane. We at Belgrano spent hours dragging a railway line (crossways) up and down behind a Sno-Cat to smooth out the ski-way from its sastrugied state. The Argentinians had less sense of urgency with this task than we did. They could not see why we wanted to leave!

All was set and the weather was good when we received the final piece of devastating news. Apparently, the insurers of Servair had refused to cover the flight and so it was off!

We all know how easy it is for those in the field to feel that HQ doesn’t quite understand the situation on the ground, and I must confess that I succumbed to those, perhaps unworthy, feelings. It seemed to me then, and still does now, that this insurance issue was not an insuperable one to overcome. We never discovered whether the matter was explored further at the time.

Sir Vivian Fuchs, the then retired Director of BAS said to me after hearing the story on our eventual return, “I would have got you out!” Who knows?

Stuck:

Anyway, there we were, and we would just have to make the best of it. The trouble was there was very little “best” to find! Logistically, as well as personally, the outlook was bleak. It was the middle of March and we could not expect to get out before November. No doubt Halley Fids will scoff but after three winters on Marguerite Bay bases with all the interest of the mountains and sledging I found the prospect of being confined to a small patch of Filchner Ice Shelf uninspiring to say the least. Especially given the extremely dilapidated and precarious state of the base and the lack of meaningful work or travel possibilities

The Base Environs:

By December 1978, Base General Belgrano was located at 77°42’S, 38°04’W. It had been moving NNW of its original location in 1955 at the rate of nearly a mile a year, latterly with us in it! No wonder there was a lot of cracking and creaking going on.

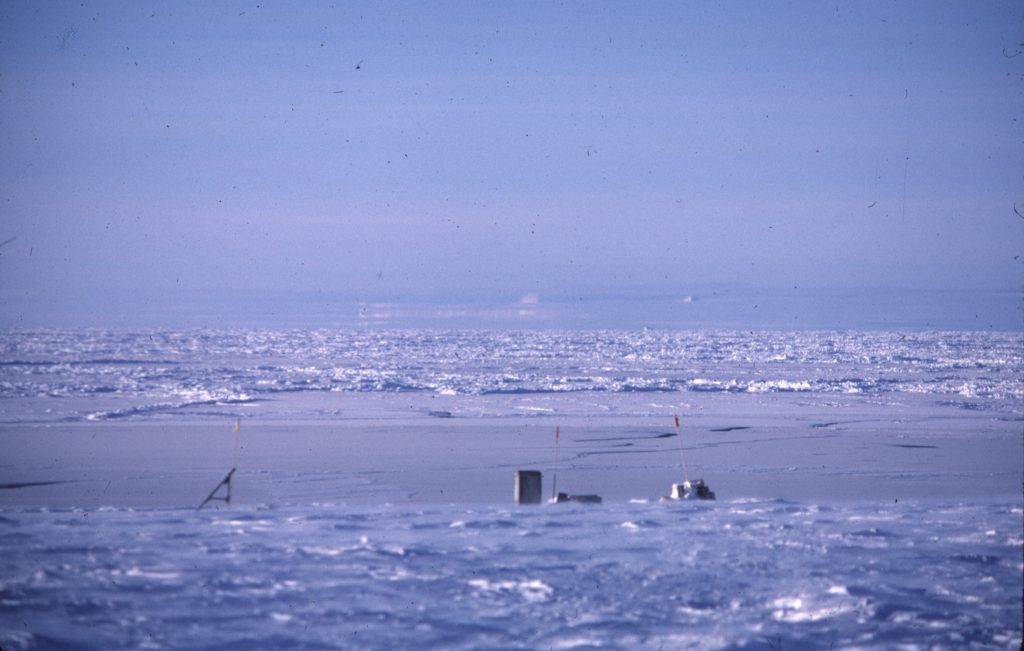

It was about 500 yards from the coast which was a lowish ice cliff. The Filchner Ice Shelf at c.166,000 sq. miles, is the second largest shelf in Antarctica, after the Ross, itself roughly as big as France! The Weddell Sea was sometimes frozen fast but was usually a jumble of floes and bergs slowly crunching their way past in the gyre of the currents (as Sir Ernest Shackleton came to know well! His ill-fated ship, “Endurance” was terminally beset only about 30 miles north of this spot in 1915).

To the west stretched the largely featureless ice shelf. About 45 miles away was Druzhnaya and somewhere around there had been the US base, Ellsworth, established in 1957 and commanded by Finne Ronne, of Stonington Island 1946/47 “fame”! This base had been given to Argentina when the U.S. abandoned it but had long since gone out to sea in a calving iceberg. Much of the furniture and useful bits of kit at Belgrano had come from there. (The rest had come from Shackleton!)

To the south lay the immensity of the Filchner and the route to the Pole. Not far south however was the huge obstacle of the hinge zone, where the shelf started to float as it inexorably slid down from the polar plateau. This was named the “Grand Canyon” by T.A.E or “La Gran Grieta” in “Castellano” as Argentinian Spanish is correctly called.

The far eastern horizon showed a slight lifting where the shelf met the inland ice which then slowly rose up in a crevassed icefall to the plateau. Just visible on the top of the first rise were a couple of tiny black specks, the Bertrab and the Moltke Nunataks.

This then was the uncompromising territory in which we were stuck. Travel was completely out of the question for several reasons. Although a party had reached the Pole with Sno-Cats from there in 1965, Belgrano was no longer a “travelling base”. The surrounding shelf was very badly crevassed and there was nowhere of interest within 200 miles anyway. Even without these deterrents, to have seriously compromised our safety would have placed a most unfair responsibility on the Argentinian Base Commander. Neither he nor anyone else had any sledging experience and it was out of the question to even ask him if we could leave the immediate confines of the base area.

Finally, we were at nearly 78°S and winter was almost upon us.

Waning Power Supplies:

As the winter drew in through April, we used to listen wistfully over the short-wave radio to the icebreakers and survey ships of the various nations which were making their way northwards from Antarctica and home. Via Rothera and Cambridge we had all let our parents and loved ones know of our predicament and we were able to send and receive our allotted 100 words per month by radio to Rothera and then onwards by telex. In fact, we were granted a double ration of 200 words per month! However, communications were never good, and they really deteriorated as winter set in. This brought difficult upper atmospheric conditions and hence poor radio wave propagation. (If I sound as if I know something about the subject, I don’t really!) The radio equipment also struggled to cope with the increasingly unreliable electricity supply. The mechanics had had to carry out major transplant surgery on the one remaining genny, utilising parts from the many dead ones. It was obvious that this wouldn’t last long.

Even at their best, the aged and long-suffering generators struggled to produce much juice and we had long periods without power, of which more later. It was a wonder to see Daniel and “Flaco” (Slim), the two mechanics coaxing the generators along, always with inadequate tools, in a chaotic, icy shed with a nightmare of jumbled, dangerous wiring draped everywhere.

Electricity was needed for lighting and of course, the radio. Cooking was done using bottled gas and heating came from kerosene stoves. The pressure lanterns, “Sol de Noches”, provided backup but were also essential for moving around the ice tunnels. We had loads of these and plenty of kerosene. Unfortunately, in true Belgrano style, we had only seven of the critical incandescent mantles on the whole base, between 23 of us, for a year! Since these fragile items didn’t last long in the rugged environment, seven would normally last us about one week!

Blackout:

Despite their valiant and unceasing efforts, we were gradually reduced to an hour or two of electrical power per day, just enough to charge batteries to run the radio. Thus, most of the base was in total icy darkness, the few mantles for the “Sol de Noches” were kept under lock and key by the Base Commander for the sole use of the cooks. Thus, there was only light in the kitchen area for cooking and eating. Interesting experiments were carried out by the scientists to try to make mantles using gauze bandages dipped in exotic chemical concoctions and left to dry. They didn’t work! There were few, if any, torches around. Even we Fids had not packed any for our sledging season in the Shackletons since there was no darkness during the summer at 81°S.

The favoured makeshift lamp that emerged from the many experiments consisted of a small tin can containing kerosene with a piece of roofing felt for a wick and a small bottle (Tabasco sauce size) with its base cut off inverted over it. Try it and you will see that it gives a light about as bright as a small match just before it goes out! You can imagine what impression it made on the utter darkness of a hut, 50 ft under the ice. However, they were all we had for a month or so and at least they stopped us bumping into each other. Little glow-worms of light moving through the tunnels gave warning of nearby colleagues.

As the last of the main generators failed, we Fids volunteered our 1000W Honda Portable Genny which we had carried on our Shackleton Mountains field trip. This was able to recharge the batteries to run the radio (until it suffered the attentions of an amateur mechanic, whence it joined its larger cousins in the genny scrapheap!). After a crisis council the Base Commander decided that he had to ask Buenos Aires for help and with extremely difficult communication conditions and a fading radio, he managed to send an emergency signal requesting that new generators, spares, and mantles etc. be air dropped to us. This was easier said than done because apart from the fact that it was winter and getting darker and colder by the day and Belgrano was several thousand miles from Buenos Aires, our base was Army and it was the Air Force that have the planes! Inter-service rivalry was a delicate factor to overcome. The operation was going to be very expensive and it was clearly difficult for Major Papa to get Buenos Aires to appreciate the gravity of the situation. Thankfully, the mission got the go ahead and we stood by for a few days as preparations were made in Argentina for the air drop.

The Airdrop:

We Fids had hopes that the Hercules C130 plane that would be used would be fitted with skis and hence could land and take us back. These hopes were dashed when we were told that the funds (US$25M) that had apparently been provided the previous year by the Instituto Argentina Antartida to the Fuerza Aerea to buy skis for the Hercules had been used instead to buy a helicopter! The latter were clearly of good use in counteracting internal guerrilla insurgencies but no good for getting us out of Belgrano.

Rothera had picked up well on this opportunity and informed BAS HQ of the scheduled flight. It in turn had contacted our families and hurried letters and presents were sent to us via the Instituto Antartico Argentina in Buenos Aires. They never reached us! And this is why!

After many delays caused by bad weather, the long-awaited day arrived, and a plane departed Rio Gallegos Air Force Base in southern Argentina on its long flight south. It was a poor day in mid-May with little light, lots of cloud and blowing snow. As the plane’s E.T.A. approached, all base members gathered outside with Sno-cats revved up, headlights blazing, Argentinian flags flapped violently from the top of the antenna towers.

Dramatically the plane appeared overhead with lights shining brightly in the gloom and circled above us about 1000 ft up. Suddenly 3 parachutes appeared from the cargo bay at the rear of the plane and they and their precious cargoes, loaded on pallets, dropped towards us, buffeted by the strong wind.

Oh, did we look longingly and despairingly up at that plane as it turned northwards and headed back over the frozen Weddell Sea.

The Sno-cats set off towards them as they hit the snow but were too late to catch one load which was dragged southwards over the ice shelf by its billowing ‘chute and out of sight! That must have been the load that contained our mail plus a lot of other supplies and goodies!

Light and Books:

Despite the losses, the Airdrop made all the difference to our lives for the rest of the winter. This factor cannot be overemphasised, given the lack of meaningful work or leisure activities.

Even though one generator and all sorts of other gear, as well as our mail, were in the lost load, we did receive enough generator parts to maintain power all year. Stocks of lantern mantles were restored, though not quite as important now that we had power. Almost as importantly, we received books. Marvellous books in English, loads of really good ones. We had requested books in messages to Cambridge HQ since there was only one on base and we hoped for a good handful. We actually received 160! They were nearly all of the typical eclectic Fids selection as were popular for the sledging journeys around that time.

These books almost literally preserved my sanity and I will be eternally grateful to those in the chain of communication who organised them. They had all clearly been acquired in Buenos Aires, many bought new but a few from the library of the British Consulate. One of them is worth particular mention, “A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush” by Eric Newby. The book is a classic and hilarious account of a climbing trip to Afghanistan in the 1950s by two young Englishmen, neither of whom had done much climbing beyond a few days training in Snowdonia. The two were Eric Newby and Hugh Carless. Hand-written on the flysheet was the dedication: “To the British Antarctic Survey from one of the walkers, Hugh Carless, Buenos Aires 1978”. Hugh Carless was Chargé d’Affaires in Buenos Aires in 1978 and was obviously ultimately responsible for the quantity and excellent quality of the selection of books that were dropped to us. When I finally reached that city many months later, I called at the Consulate to see him and thank him. Alas he was on leave and I never did get to tell him just how much all the wonderful books, but particularly that one, meant to us.

So, we had power, light and 160 books for the rest of the winter. We settled in for a long lie-up!

The Base Itself:

Down in the ice caves and tunnels where the base huts were located the situation was scarcely less bleak than “up top”. Slightly, and sometimes only slightly, warmer, but much dirtier and almost indescribably chaotic.

There were two main huts, one long one housing the sleeping quarters, radio shack, bathroom (ha!), surgery (bigger ha!) and wine store. The other contained the kitchen, dining room, games room and daily food store.

The wine store was the site of a spectacular incident not long after our incarceration. Several of us were gathered idly around a stove in the corridor outside when this happened and we were startled by the crashing of breaking bottle coming from the locked store nearby. An interior wall had been finally pushed so far off vertical by the pressure of the surrounding ice that it tipped its contents of a 100+ bottles onto the floor. Almost instantly a great torrent of wine flowed under the badly fitting door and rushed off down the angled corridor, which was impregnated with old diesel fuel and the grime of decades. Within a minute or so, as the flow abated, the torrent became a long, frozen wine-glacier!

The generator shed lay between these two huts at the start of the ice tunnels. These ran off at stooping-height through the ice to clothes stores and cold food stores, “frigorificos” in Castellano. Other even more constricted ones led several hundred yards to old and practically redundant scientific labs where upper atmospheric geophysics may once have been studied. Originally sited well away from the electrical and magnetic disturbance caused by the generators, they were by now mainly used by the scientists to play loud rock-music away from the army chaps who preferred traditional Argentinian “Folk Music”!

There was also a “garage”, just a large cavern in the ice, linked to the surface by a long ramp, wherein lay the remains of several “dead” generators and Sno-cats.

They had all succumbed to old-age or mistreatment at the hands of generations of dodgy mechanics. Even here, the ice ceiling was inexorably descending and beginning to crush the machinery stored there. The garage was also used to store the gash and ice blocks which had been cut from the ice above the huts. This was a continuous “Forth Bridge Painting” exercise. When the garage was full, we would wait for settled weather to open the ramp and carry or pull the rubbish etc up to the surface on cargo sledges. (Can’t remember what we did to it then?)

As already described, the huts were very badly damaged by the pressure of the ice. The Quebracho wood column which formed a corner of my room was being crushed downward at the rate of nearly ½ inch per week. The rifle shot-like cracks that came from it as it bowed and splintered under the pressure made for an uneasy sleep. There were beams and pillars everywhere in a similar state. One bottom corner of my door touched the floorboards; the other was 6 inches in the air! The wooden floors were bowed and buckled, and walking was an unsteady business. And everywhere the stygian gloom.

Base Personnel:

The base complement was 23; 20 Argentinians comprising 11 Army “Ejercito”, 2 Air Force “Fuerza Aerea”, 7 civilian scientists/technicians and us 3 Fids. The scientists had obvious skills, but little scientific work took place since most of the ancient equipment and apparatus was defunct or moribund. Additionally, the power supply to run it was hopelessly unreliable. Apart from some auroral observations in the winter and summer sunshine recordings, not much data was collected. We felt sorry for the scientists, (not normally a G.A. trait) but they had obviously thought there would be useful work for them in Antarctica.

Still, the personnel were paid more money down there than they were home. In fact, being on an Antarctic base was the only way most of them would be able to afford to buy a house and/or car back in Argentina. One of the Army lads told me he earned about 12 times normal pay. Even more than for fighting left-wing guerrillas in one of their remote provinces. Arguably safer too! (This was the time of the so-called Dirty War, “La Guerra Sucia”, in Argentina).

The base members were great fellows and very good to us and easy to get along with. The Base Commander, Mayor Hector Raoul Papa, was, as his name implies, a kind, fatherly figure who was quite happy to let the base run in an easy-going manner. His brisk young lieutenant, “El Teniente”, was a slightly more rigorous military-man, who was keen on saluting the flag and maintaining some of the military routines. A good fellow for all that.

Although most of the men came from Buenos Aires, some of the other Argentinian provinces were represented. One of the (two) cooks, Ramon, was a stocky little forester from Missiones, bordering Brazil and Paraguay. His native Indian language was Guarani, and he was ribbed gently about his poor Castellano. Another man, Angel, was a pure Andean Indian from Salta, the province in the far North West on the Andes.

Most spoke very little English but luckily, one of the young technicians, Jorge, was pretty fluent and did most of our translating. Gradually our Spanish improved and we were able to get by after a few months.

Base Routine:

There was little routine about base life at Belgrano and what there was to start with, tended to relax further as winter wore on. Usually there was a morning parade (indoors of course) at which the flag was saluted, and the Major received a brief report from El Teniente about work that needed doing and who was required to do it. This sounds very formal and militaristic, but it was rather casual and haphazard, although at times, a useful way of starting the day.

Apart from the few obviously essential tasks like “gash runs”, when a large team was needed to open the cover at the top of the ramp and drag all the accumulated gash outside, there was little attention to any other form of base maintenance and repair. This was perhaps because the base was due to close at the end of the season i.e. early 1979. So, it was usually John Wright and me that brought such tasks to the Major’s attention but we usually did them ourselves. It was quicker and more certain that way and we could always ask for a team to help when necessary. Otherwise we were all stood down for the day. There was an awful lot of festering and indeed the base doctor, a very funny, chain smoking Captain, and nominally the Deputy Base Commander, was nicknamed “Dr. Tutankhamen”, owing to the amount of time he spent lying flat in his bunk!

The physical condition of the base has already been described so John and I set about trying to sort some of it out.

The biggest task was clearing the indescribable chaos of twisted and splintered wooden beams, railway lines and other debris from the area between the roof of the huts and the base of the slowly descending ice. This was done by hand, a strenuous and often dangerous job. The large pieces of wood and metal were partially trapped in the ice and were under extreme stress. As they were cut or chiselled out, they tended to whip around in often frightening and unpredictable ways. Given the gloom and the slippery aluminium skin of the hut roof on which we had to work with hopelessly inadequate tools it was gruelling work. Cutting through railway lines with blunt hacksaw blades takes time! (These rails had been made in the early part of the 20th Century in Workington, Cumbria, a place I worked in my later career. Britain had built a lot of railways in Argentina and some of the old rails had ended up at Belgrano!)

Once we had cleared this space, a progressive job taking several months, the underside of the ice was accessible and so could be sawn and hacked away on a regular basis to stop it crushing the hut any further. It also meant this ice could be melted for water for washing. The trouble was that the process of snow accumulation and the cutting away of its bottom layer meant that this ice that we used for washing contained diesel and other pollutants that had contaminated it when it was the upper fresh snow surface, years previously.

As well as the crushed beams and other rubbish, there were huge, dangerous caverns in the ice between the hut and the surface. These were caused by the heat from the generator exhaust or the chimneys of the heating stoves which reached 50 ft. to the surface, and then a few feet further above the snow.

They ran through vertical stacks of wired-together empty oil drums, designed to provide some level of insulation against the heat from the chimneys from melting the surrounding ice. It had not worked, and these stacks were very unstable and dangerous.

Youth, Phil and I set about replacing and securing these towers. Although this was work that desperately needed doing, I suspect we went for it since it enabled us to break open our Fid “rescue” sacs and get the climbing gear out. We set to with abseiling, prussiking and other climbing and crevasse techniques and got the job done. It impressed the Argies if nothing else!

Strange as it may sound however, we were glad of such work. Although difficult and sometimes dangerous, it gave us interest and exercise and passed the time, of which we had plenty.

Washing and Showering:

Another major task that Youth and I undertook was to construct a drainage conduit to take wastewater from the washroom to where it could drain away into the snow. After 20 years, the whole ice surface in the gap between the wall of the washroom and the snow had frozen into hard water ice as the wastewater had permeated it. Now it would take no more and the water just froze in the outlet pipe. Nobody seemed to worry much about this. Washing was not a high priority so what matter if the water did not drain away? It didn’t make much difference to our permanent state of grime anyway.

The wall of snow was only a few feet from the outer skin of the hut so we had to cut a tunnel about 5-6 yards out from it until finally we reached a softer area of ice area that had not been inundated and the thus water would drain away. We then cut and welded several “holey” old pieces of corrugated iron sheet together to form a makeshift drainage conduit and set it at an angle which allowed the water to run through to the drainage area quickly enough to stop it freezing before it got there. Youth did wonders with the oxyacetylene cutting kit with none of the correct nozzles for the necessary tasks. This took us over a week of solid work to complete.

Taking a shower was an epic character-building experience. The gash man of the day “la guardia” was allowed a shower, a doubtful privilege that not many took advantage of. A tank, heated by a stove-chimney system had to be first filled with ice blocks (cut from the ceiling layer, as described). When it was deemed warm enough, the dangerous ritual took place. The only available heating for the frigid metal-cladded shower cubicle was a huge industrial pressure burner, a giant “Primus” type stove. It was about two ft. high and was known as “la Chancha” or “the Pig” in Argentinian slang. Unfortunately, it lacked its flame spreader-ring so when it could eventually be coaxed into life it emitted a huge roaring jet of flame like an inverted Saturn Rocket! If one was brave enough to try it, this could rapidly heat up the shower cubicle, at least above the two ft. level. One’s lower legs and feet remained very cold!

When “la Chancha” had perhaps stayed in long enough to warm the upper part of the cubicle, one had to edge on the slippery and cold metal floor, stark naked, past the roaring “Pig” and soap up. Since there were no prickers to keep the stove nozzle clear, it inevitably chose the moment when this was done and one’s eyes were full of soap suds to go out. The cubicle was then instantly filled by blinding clouds of kerosene vapour and it became a scrambling, scorching nightmare to shut the thing down and complete the shower before the temperature dropped to well below freezing To compound the whole unpleasant experience, the diesel-fuel impregnated water (as explained above) stung the eyes and left black specks on one’s skin.

Science (not much):

Fids will not be surprised to learn that the base was primarily there for political and military purposes. It had been due for closure for several years due to its appalling condition and increasing proximity to the ice front. As has been described, little science of value was possible and even the meteorology was spasmodic and of doubtful validity, consisting of basic temperature and pressure readings taken from instruments in a closed (ex-food) box located a couple of yards from the exit shaft and a generator exhaust pipe.

Things may have been better in the past. A trip to the Pole was undertaken from there in 1965 and there had been an Argentinian equivalent of TAE’s South Ice advance base, Base Teniente Sobral on the southern edge of the Filchner Ice Shelf. This was named after the first Argentinian to winter in the Antarctic (1904). Interestingly enough, one of the Sno-cats that had been to the Pole was still being used around Belgrano when we were there.

Food and Parties:

Even if there were work duties, they seldom, if ever, extended beyond lunchtime. As is usual in most “Latin” countries, lunch was the meal of the day. Although the quality and variety of the food was not high, the cooks tried hard with the limited resources at their disposal.

There was a lot of mashed potato, cheese, dried ham, corn meal, tinned sausages and plenty of meat, particularly pork and beef. Saturday night was Pizza or Empanada (pasty) night and the cooks would work hard all day producing wonderful home-made pasta. There was not much fibre and this and the temperature in the hole-in-the-floor bog, meant trying times were had by all!

However, the wine, cigarettes and “craic” more than made up for the scradge. The remaining stock (still plentiful) was carefully rationed by the Sergeant-Major. As winter moved on, the frequency of the parties increased, and little excuse was needed for them. No longer were they held only on national holidays or religious feast days.

Other important occasions such as the birthday of the girlfriend of El Teniente (who was in Argentina of course), were held to be cause enough and celebrated wholeheartedly!

Saturday night was also Movie Night. Once again these were of a wonderfully Belgrano flavour! There was always an old Italian “Pathé News” type film (all celluloid of course) which made for fascinating news of the Pope’s official duties in Italy in the mid-1970s!

The main feature, Whichever ancient film the main feature happened to be, was always so badly damaged or incomplete that we never got to finish one the whole time we were at Belgrano. They would sometimes develop a big melt-out after a few minutes or we would have 3 spools of different movies (quite good actually), or the power would fail. Lots of rhubarb and cheering, just like Fids. “Ningun problema”, we would play cards instead!

Table football competitions were a must but though often frantic, I found these much less fun than the “Truco” card competitions. This enjoyable and complex game is very popular in Argentina (and other South American countries) and is played with a set of “Spanish” cards. Secret signals are exchanged between partners and thus I fared passably well by playing with Jorge, the best English speaker, so we exchanged signals in English which our opponents did not understand. Of course, we, or at least Jorge, could obviously follow any signals in Spanish that our opponents might use! These competitions often went on until 5 or 6 o’clock next morning.

Here Comes the Sun:

At those high latitudes we had two months of darkness and another two of dim twilight, thus 4 months without the sun. Even the twilight was pretty dark, especially since there was often cloud cover. Not that there was much reason to go “up top” although I tried to get out every day unless the weather was too thick for safety.

The sun reappeared on 18th August and there were outstanding outside jobs such as extending the shaft up which our access ladder climbed.

This had gradually drifted over and although the Argies did not seem too concerned, Youth and I considered it important that we should be able to get out, so we decided to fix it. Joinery in the minus 44°°c was trying and the drill bits were very brittle at such temperatures.

The lowest temp. we had was -57°c but as usual, these very low figures occurred on cloudless, windless days. These were preferable to the warm days when it crept above -20°c since then the warmer air from the huts caused the ice ceiling to melt and leaks and drips would easily get through the damaged skin of the huts.

It was down to -53°c on 22nd September and a few days previously we had had over 100 knots of wind, rugged stuff for this area. The return of the sun did not mean instant warmth!

War Drums:

We had a bit of excitement in mid-September when Argentina and Chile nearly came to war over some disputed islands in the Beagle Channel to the south of Tierra del Fuego. As an Army base we were put on alert and did a food inventory in case the relief icebreaker, Q4, was involved in hostilities and the base could not be relieved at the end of the current season and the base personnel would be there for another year! We did discover that we still had 1600kg of meat, 600kg of flour and 500 bottles of wine. It sounded a lot to us Fids. Anyway, things calmed down after both countries accepted a process of Papal arbitration (the method used to divide South America between Spain and Portugal in 1494!).

Rising Hopes:

From August onwards, we began to get radio reports from Rothera and Halley about the plans for the forthcoming BAS season. The planes were due at Rothera on 20 th October so we could begin to think seriously of being picked up, or “rescued” as we thought of it. Particularly good news was that Giles Kershaw, our peerless polar pilot and my good friend, would be down again. With Giles around, our chances of an early pick up were maximised.

My spirits were further raised by being able, very occasionally, to talk over the radio with my then girlfriend (later wife), Anne, who lived in Indianapolis at the time. Unlike in British Antarctic Territory, there were no restrictions on the Argentinians speaking by radio with their friends and families back home, if communications conditions permitted. All that was needed was a “ham” radio operator in Argentina, or in my case, the U.S.A. who was able to transfer or “patch” the call via the telephone system, to the required number. As we moved from winter to spring, radio transmissions improved, and I managed to contact Anne on several occasions. She had to pay “reverse charges” for the phone calls!

I also took advantage of the increasing daylight by going for daily walks on a circuit around the base. This took in the ice cliffs on the coast. There was seldom fast ice right up to the cliffs, normally a narrow shore lead of shifting brash ice. The scene out over the Weddell Sea was often impressive with tremendous pressure ridges and a chaos of icebergs. I used to fancifully wonder if I would spot a piece of timber emblazoned with the name “Endurance”, a relic of Shackleton’s ship, forever circling in the Weddell gyre. It was this area of coast he was heading for in 1915 when his ship was beset, not far to the north. I never did!

The exercise and increased hope meant that I was sleeping better by now, after a winter of desperate insomnia. The Argentinians were beginning to think about the January relief and were getting more involved in our major clear up projects involving the crushed pillars, beams and railway lines. As it so happened, the base was abandoned at the end of this season so much of the work could be thought of as a waste of time. However, at the time, it seemed that it had to be done.

Preparations for Relief:

October finally arrived and we had optimistic hopes that we would be rescued that month. However, BAS logistics and some problems with our planes and ships meant that we got the depressing news that it was now going to be November before the planes got to Antarctica. We had been working on getting back to Rothera from Belgrano and then having to spend a couple of months there until the first BAS ship arrived in January. However, I could see from the various ship/plane schedules for the early part of the summer season that if I could somehow get a lift from Rothera up to Marambio, an Argentinian Air Force base on Seymour Island, I might be able to fly out from there. Seymour Island is on the east coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, not far south of Hope Bay. It had a gravel runway that enabled wheeled Hercules and Twin Otters to operate to and from Argentina.

But we had to get out of Belgrano first.

We began some work on the ski-way landing strip that was badly sastrugied after the winter storms. These sastrugi would have wrecked the plane’s landing gear so we broke them up and smoothed them with a Sno-Cat.

As we all began to get demob happy, the parties became even more frequent and riotous. The Sargento Primero (Sergeant Major), who kept the key to the booze store and had been quite careful with his rationing, began to loosen up a bit and the taps were opened, so as to speak! There were always lots of patriotic speeches after dinner at the parties. Even us Fids got in on the act and would tell the Argies (in halting Spanish) what splendid fellows they were (which was true) and how much we had enjoyed being at Belgrano (which was less true).

Relief at Last:

Eventually, in early November, we heard that the BAS Twin Otters had left Canada on the long journey south through the Americas. At last, after our interminable sojourn, it seemed that an end to it was in sight.

Things started to get exciting as we picked up radio comms. between Rothera and the planes as they approached Punta Arenas in southern Chile. We then we tracked them on the long, hazardous flight across Drakes Passage to the Peninsula and were mightily relieved when all went well, and they arrived safely at Rothera. They had not been at Rothera for more than a few hours when, typically, Giles Kershaw was on the radio to us, ready to fly and wanting our weather report. He was a tireless and expert flyer and it was a great privilege to work and fly with him so often over several years.

On 18th November 1978, after our stay of 9-½ months (286 long days) at Base del Ejercito General Belgrano, the BAS Twin Otter VP-FAW, finally arrived from Rothera, piloted by Giles. Were we glad to see him! After many fond farewells with our Argentinian “hermanitos” (little brothers), we left Belgrano and flew up to Halley to deliver the mail! The base there was led by an old Stonington sledger, Miles Moseley, and he had organised a great welcome and party for us. After a couple of days relaxing at Halley, we flew back across the Weddell Sea to Fossil Bluff and Rothera.

After 3 weeks at Rothera, I did eventually fly out from Marambio on a Fuerza Aerea Hercules C130 as planned, again grateful to the Argentinians for their understanding and generosity. Then I was back to the UK via Rio Gallegos and Buenos Aires.

Youth and Phil decided to stay at Rothera, wait for the scheduled relief by ship and experience the bustle and interest of a Marguerite Bay sledging base during its summer season. It was nearly Christmas that year before I finally got home and met up with my family and Anne, who was over from the U.S.A. We were married a year later, and it was a marriage worth the wait!

Belgrano Reflections:

Personally, I had found our interminable stay at Belgrano very trying indeed. My three winters and four summers with FIDS at Marguerite Bay had been just brilliant. After dog sledging for thousands of miles amongst the mountains and on the plateau of Graham Land, the seemingly endless and aimless incarceration at Belgrano was extremely depressing. I also felt angry at having been betrayed (as I saw it) by the Soviets and frustrated at not having got out in February when I felt that chances were missed. I was continuously tortured by the fact that I had somehow missed something in my negotiations with the Soviets and hence condemned Phil, Youth and of course myself, to this difficult episode.

I still wonder about that.

Despite these thoughts, I will ever be grateful for the friendliness, kindness and understanding we received from our Argentinian colleagues. The wonderful Base Commander, Major Hector Raul Papa set the scene with his easy but firm management of the base and fatherly tolerance of us. It must not have been easy for him trying to explain to his Army superior officers, why he was harbouring three Brits. on his military base!

I keep in close touch with one of the Argentinian lads, Jorge Pahor, my old Truco partner, and have met him and his family several times in Buenos Aires. He gives me news of some of our other colleagues of that time although I often wonder, with sadness, if any of them fought and perhaps died in the 1982 Falklands Islands’ War.

I look back at it all as having been a most unusual and quite surreal experience. It was a remarkable year in a most extraordinary place and a hell of a way to learn Spanish!

Postscript:

Belgrano I was abandoned in early 1979, at the end of “our” year.

Belgrano II base was built on the nearby Bertrab Nunataks at the same time. Being on rock it is still there.

Abandoned bases Shackleton (UK T.A.E), Belgrano 1 (Arg.) and Druzhnaya (USSR) floated out in 1986 in a 2,300 square-miles iceberg, the (then) second biggest calving in history.

Some years later I was having my hair cut in Workington, Cumbria when a report came on the salon’s radio that a huge iceberg was drifting out of the Weddell Sea and threatening shipping. The report went on to say that the iceberg contained the remains of an Argentinian Base. The hairdresser must have thought me most odd when I told her, “I spent a year on that base”!

Giles Kershaw, one of the greatest Polar Pilots, tragically died in a Gyrocopter accident on the Jones Ice Shelf in 1991. He had left BAS a few years previously.

The wonderful Major (later Colonel) Hector Raul Papa died in 2017. He was in his 80s by then.

This account is largely taken from my daily diary kept at the time. The opinions expressed are entirely my own. It may not necessarily accord with the recollections or thoughts of my two Fid companions, Phil Marsh and John Wright. I entirely respect their version of events if they differ from mine.

They were good companions and we shared a rare experience together.

I am grateful to them for their good humour and fortitude.

(All photos by Dog Holden unless otherwise stated)

Dog Holden, Perthshire, 2020