It had been constructed by a building party under the direction of John Cunningham, the overall base leader of our parent base at Stonington Island. The plan of the hut was simple, a rectangular structure measuring 19 feet 8 inches in length and 14 feet in width. Insulated, prefabricated walls in a framework of iron girders formed the shell. The roof was securely held down by cables anchored into concrete. A very heavy door opened into a minute, curtained porch whose side wall formed part of a partition which acted as a radio shack. Opposite the door a small room was partitioned off to act as a WC, though we preferred to make other arrangements for our toilet, so we adapted this area to be a food cupboard. The main living space, 13 feet by 14 feet, in whose confines the three of us would spend twenty-two out of twenty-four hours for three months, was dominated by the stove, whose warmth provided the means for heating the hut, melting the blocks of snow for water, and for our cooking. Along one side of the living space was a narrow writing table which Brian used for his geological notes and reports. The solid table in the centre was used for dining and for John’s artistic endeavours, whilst I always used the bench in the radio shack for whatever I was doing. We had a side cupboard, usually littered with rock fragments, and we had a bookshelf which supported our meagre library. Each night we retired to our sleeping bags, using three of the four bunks arranged in two tiers along the end wall. On the opposite end wall was a large working bench for heavy work. We had no chairs, so we had to find the most comfortable boxes, and we had no proper washing facilities apart from some small plastic hand bowls, but the tins in which boxes of cornflakes had been packed enabled us to have a stand-up strip wash when we felt so inclined!

Our first night was very cold as we had no heating and the temperature dropped to 2°F. We rose early and worked solidly from 10.00 a.m. to 10.00 p.m. on priority number one.

March 5th. A cloudy, calm day with temperatures about 25°F gave us good opportunities to work outside and we started the generator shed. We are all complete novices but our effort – starting from a desultory piece of 4 x 2 wood nailed onto the side of the hut – gradually developed into a really sturdy and nice-looking hut.

Within three days we had completed the exterior, double-walled, insulated with fibre glass, and with two windows. A day or two later we had finished constructing a roof and had improved the floor with a layer of gravel. On the 11th I commenced wiring the ,hut, installed the switchboard and ran the generator for three hours; it worked! By the next day we had five lights and the 119 radio set all functioning.

Once we had reached the stage where I could carry on with the generator on my own, John set to work on the Rayburn stove. We had been using a very poor Uruguayan portable stove and we need to get the main stove in operation. John started on this work also on the 11th. It needed assembling and cementing, and two days later we were enjoying its warmth and cooking space.

During our last few days at Stonington Island, I had rushed around putting together a basic set of meteorological instruments so that we could carry out regular observations of the weather; unfortunately, most of the new equipment was deep down in the hold of the John Biscoe, and was therefore inaccessible. By the time our weather station had been set up, we had almost all of the necessary instruments. A marine barometer was installed in the hut, alongside a barograph. A maximum, a minimum, and an ordinary thermometer were installed in a crate which had been adapted to function as a screen by drilling holes in the ends and making rudimentary louvres. The screen had the attributes of good ventilation and correct height, though we only had aluminium paint so that there was some error. This was set up on the fourth day after our arrival and regular observations were made from March 8th throughout the entire time we spent at the base.

Whilst I worked on the electrics and weather station, John worked on getting the radio working. We used a 119 set, and John was soon able to make contact with Stonington Island. Until we could link it to the general power supplies it was necessary for one or other of us to crank a small generator by hand.

Once we had heating and lighting within the hut, we turned our attention to sorting out the food which had accumulated outside the hut during the many flights which had taken place before we arrived. Normally the supplies for a base are carefully thought about so as to ensure an adequate quantity, quality and diversity. Because of the sudden rush to establish Fossil Bluff, our supplies did not always meet these requirements. We were immediately satisfied that the boxes of sledging rations were sufficient for any journeys we needed to make during the year (these were boxes with food for two men for ten days, suitable for carrying on sledges). What concerned us, however, was the quantity and variety of the rest of the food, our basic source of sustenance. The weight factor in carrying our supplies in the aircraft resulted in our having a limited, but we thought adequate, supply of food.

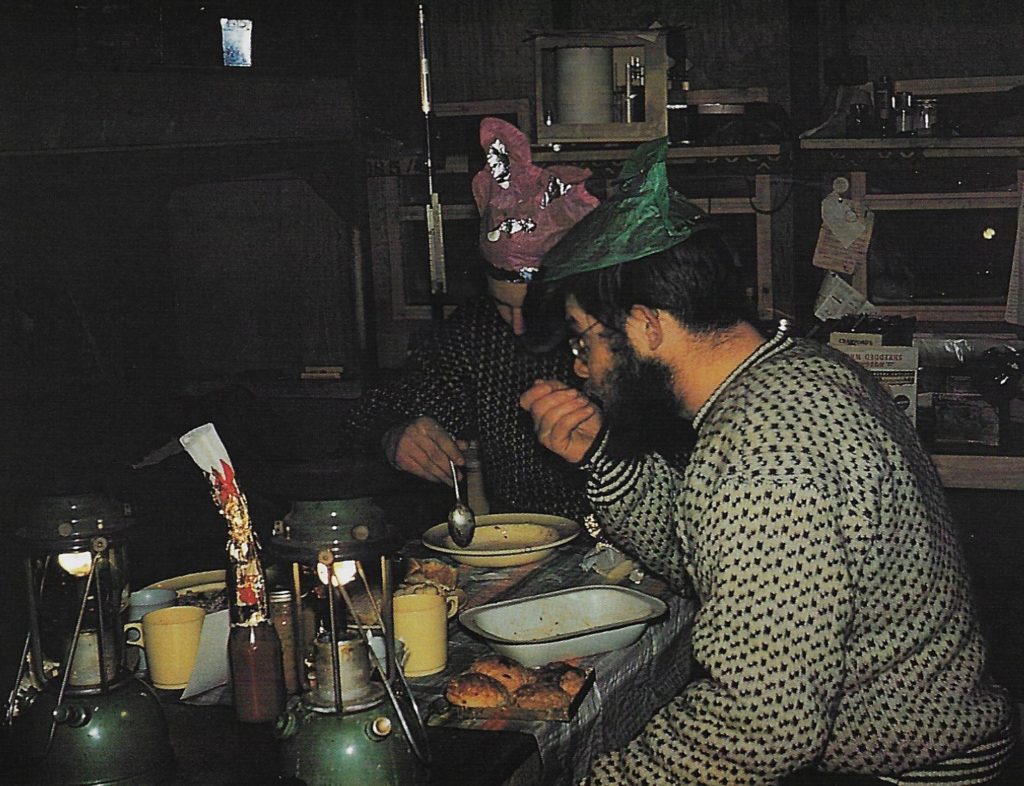

We soon became aware of problems. It was unfortunate that the crates of vinegar and piccalilli, which quickly froze and shattered, had wasted valuable cargo space. We were perturbed to discover that five boxes which should have contained sugar contained tinned tomatoes. There were insufficient tins of vegetables, and persistent freezing rendered the sprouts and the few tins of potatoes into a soggy mass. We also had very little flour and hardly any dried egg. But we were well provided with some interesting ingredients, including caraway seeds, glacé cherries, and peppercorns! Never the less, despite these shortages, we felt that we had most of the necessities to provide for a reasonable diet. Meat figured .high on the menu, and we had a good supply of dehydrated meat produced by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries in Aberdeen. This provided us with beef steaks, pork chops and lamb. We also had excellent quality dehydrated fish. MAFF also produced dehydrated fruit which proved excellent; however, because we only had limited supplies of sugar, taken from the sledge boxes, we rarely used them. We also had good supplies of tinned fruit. By some strange chance we were overwhelmed by dehydrated runner beans, which appeared at virtually every meal for the whole year, after a few months taking the place of potatoes. We also had some boxes of ascorbic acid pills. As we sorted through our supplies we carried them and stored them under the work bench, and filled the shelves of the store cupboard with our immediate requirements. We had one flagon of rum. in a basket, and a few bottles of sherry and wine; our alcohol took up very little space.

Inside the hut, Brian and John put together various cupboards and work benches so that gradually we had a suitably clear living space.

We sorted out the other supplies; we left the dog food, nutrican, outside; things such as the linoleum we carried inside so that it would soften in the warmth before we attempted to lay it. We stacked up the sacks of coal, moved the fuel drums and arranged the surplus timbers so that we knew where to look for them should they drift over. Within two weeks of our arrival we could begin to turn our attention to other matters. Brian had already spent time, sometimes whole days, up on the slopes, and he was anxious to really get stuck into his work before the light failed and. the snows came.

By now we were getting to know each other really well. John Smith was twenty-eight, from Kent, and he had already spent two winters in the Antarctic. He had now returned for a third season and it was natural, therefore, that he was designated as officer in charge, whilst John Cunningham (the base leader) was at Stonington Island. John was a meteorologist but he had used his leisure time to produce many beautiful paintings of Antarctic scenes as he had seen them at Deception Island in 1956, and at Detaille Island (just south of the Antarctic Circle on the Graham Land coast) during 1957. John had the distinction of being on cook at Detaille Island on the occasion of the visit of HRH Prince Philip to the base when on his world lour. John was unusual amongst the Fids in that he had recently been married – to Frances.

Brian Taylor was twenty-four, and was the geologist. He was a graduate from Swansea, University of Wales, and I had first met him during his preparatory work at Birmingham University in 1959. He had made the long journey on the Kista Dan as a cabin mate of mine, so we had already spent 110 days in close proximity. He had returned home after the unsuccessful bid to reach Stonington Island in the previous year.

I was twenty-five years old, and had graduated with a degree in geography and economics, as well as a teaching qualification from the University College of North Staffordshire (Keele University), followed by a year of teaching m Hertfordshire.

We soon organised ourselves. In such a small base one man could do all the basic jobs, so after the first few days we each undertook, a week at a time, to do all the duties. These included keeping the fire going, bringing in the coal, collecting and melting down the ice/snow blocks, keeping the hut reasonably clean, and – perhaps most important I of all – doing our best to create culinary masterpieces from the available supplies. The other two weeks in the cycle we had complete freedom to do whatever we wanted to do. All of us wanted to spend as much time outside as possible and we explored various places in close proximity to the hut. On March 14th, the weather was favourable for John and me to make what we believed to be the first ascent of the mountain behind the hut, which we estimated to be about 2,500 feet above the base, and which we named ‘Pyramid’ because of its perfect shape. We made a false start, ending up at the bottom of some difficult scree slopes before finding a way up the ‘Gulley’ and on to a ridge which led to the top. It only took us an hour or so, but we enjoyed a view that no one else had seen. We were so pleased with ourselves that when I got back to the hut I decided to make the first bread at Fossil Bluff. I found certain difficulties in this because we had no scales, no bowls, (except for plastic washing-up bowls) and no baking tins. The loaves were very successful, however, though an unusual shape.

The absolute silence, broken on]y by occasional! bangs caused by the ice settling, took some getting used to, as did the complete absence of any moving creature, other than ourselves. We were positively thrilled, therefore, when on March 18th two skuas appeared. John and I rushed outside with all sorts of food to attract them, so delighted were we to see life? Unfortunately, they only stayed around for ten minutes and didn’t partake of our offerings. It was six months before we saw another living creature.

When we decided not to use the facilities provided in the hut for toilet purposes, we had to arrange an alternative facility. We therefore started to chip down through the ice with our axes to carve out a ‘bogloo’. It was an excellent form of physical exercise and we worked on it for many days, eventually producing a stepped shaft which led down to a long corridor, off which we constructed cubicles with proper seats spanning deep holes. We all found the use of our bogloo a delightful experience after the cold squattings on the ice!

One day when I was on cook late in March, I decided to look again at our sad pile of broken bottles of frozen vinegar and piccalilli. After much nicking, and removing the bits of glass, I rescued one full bottle of vinegar and three bottles of piccalilli, a very satisfactory outcome!

By the end of March, we had become attuned to our environment and we were well settled into our base. Meanwhile the days were shortening and it was getting colder; the autumn season was well advanced.

Cliff Pearce, Met, Deception 1960, Met. Fossil Bluff 1961