Drama and Deaths in Bill’s Gulch (continued)

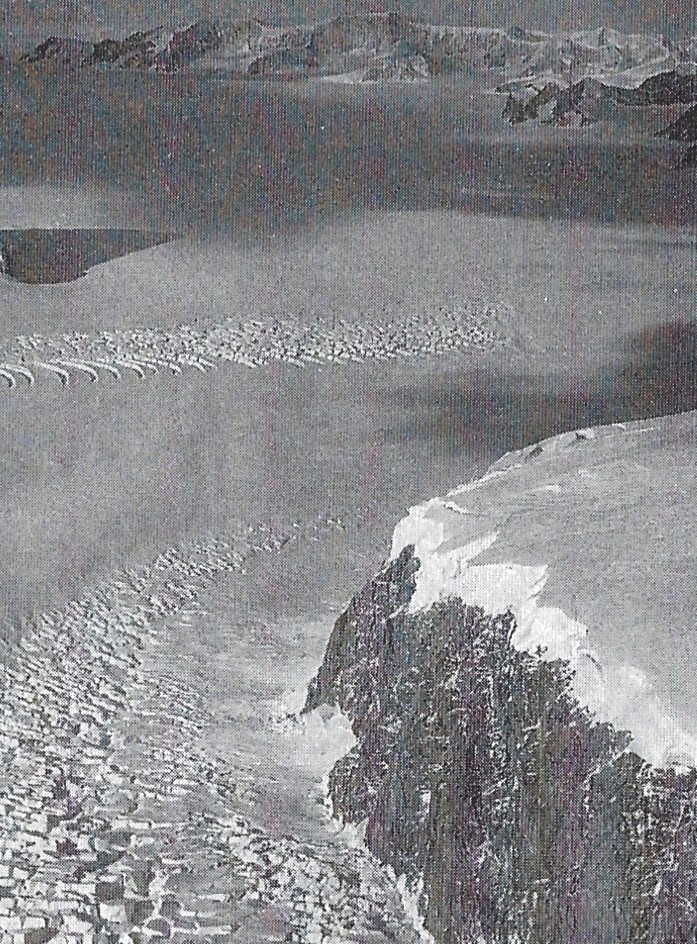

(Photo: Ben Hodges, Stonington 1961, 1962 and 1963)

Bill’s Gulch was a fearsome alley of jumbled ice falls and crevasses caused by plateau ice spilling steeply towards the sea. It was a frozen cascade of moving ice which forever changed. Spend a night camping in the Gulch and you know it is a restless place. The ice speaks to you in a voice reminiscent of gunfire. Each report signifies a crevasse splitting or a serac cracking. And so congested can it become that one field party actually pitched their tent on a crevasse bridge! The route through is a tortuous switchback where parties frequently lose sight of one another. Teams following the trail breaker are anxious to stay in line astern.

It was mid-May by the time the six-man East Coast party made their scheduled rendezvous at Three Slice Nunatak at the east end of Trail Inlet. Temperatures in the area had already been recorded down to -47° C, and daylight was becoming scarce as midwinter approached. As it was still too early in the season to guarantee sea ice in Neny Fjord the return via Bills Gulch was unavoidable; a total distance of sixty miles. Nor was it made any easier by the sledge being unduly overloaded with redistributed equipment. The reason was that one sledge was being used to stretcher an injured geologist. A few days earlier he had become victim of a ‘Whiteout’ – the invisible landscape of polar environment . Such was its deceitfulness it has lured two dog teams – the Trogs and.Spartans – over a thirty foot ice cliff. What could be salvaged had been but one of the drivers was immobilised with a partial paralysis of his neck and arms. Further delays through enforced lie-ups due to blizzards and poor visibility meant that it was not until 28th May that the convoy of five teams set foot on Bills Gulch. Temperatures that morning were a respectable – 15°C.

In difficult terrain it was customary for the teams to close up at intervals. At 11.00 am they did so but with a stunning realisation. The third sledge was missing. Man, sledge and the nine dog complement of Terrors had disappeared. The conclusion was immediate – they had been claimed by a crevasse. And Bill’s Gulch was full of them either lurking beneath a snow cover, gaping, or broken open by a passing sledge. Cautiously retracing the route a yawning hole was found cut into the lip of which was a severed dog trace. Duly safeguarding the dog teams the men belayed and peered over the edge – fifty feet below the motionless Kelly lay wedged between the sidewalls. Further down the blueness turned to blackness but with sufficient light to distinguish ‘irregularities’ in the ice. There was no barking but there was a voice. Remarkably the driver, Noel Downham, had survived and was able to shout up that his injuries amounted to no more than a damaged thumb and bruising.

It took a full four hours to retrieve what was recoverable. The splintered sledge was irreparable. However, by far the greatest loss were two of the dogs. Nick broke his back and had to be destroyed, whilst Jade died from internal injuries. Both lie buried in the crevasse with the remnants of the sledging unit. Of the surviving dogs Jet recovered form a damaged leg whilst Bryn overcame severe shock. At camp that night the men mourned their losses but counted their blessings. There was also time to speculate as to how anyone could survive a vertical drop of 120 feet (depth verified by climbing rope).

The driver clearly remembered that it was the back of the sledge which had broken through the snow bridge. This is not uncommon and under normal circumstances the forward momentum of the sledge clears the danger. Noel, loosely attached by a waist-loop to the sledge handlebars either jumps across or is tugged over. Not so on Bill’s Gulch where the loads were heavy, the gradient steep and the going very slow. As the rear of the sledge dipped the force of gravity dragged the team backwards and into the void. When Noel struck the bottom his fall was apparently cushioned by the thick snow bridge on which he must have ridden. Yet his most conscious memories were first avoiding being hit by the sledge, then by the dogs weighing up to l00lbs which crashed helplessly around him. He also looked in despair at the tiny circle of light high above, through which he had fallen, only to watch the two following teams leap across unsuspecting of the tragedy and predicament below.

Five days passed before the East Coast party finally arrived back at Stonington. It was June and the recorded temperature that day was -35°C. The eleven base members had much to relive. They shared a gladness brushed with sadness. Outside where it began to snow the reunited dogs curled into a cocoon of their own body warmth; the surviving Terrors with Spartans, Trogs, Moomins, Giant, Komats and Ladies.

Geoff Renner, Geophysicist, Stonington 1964