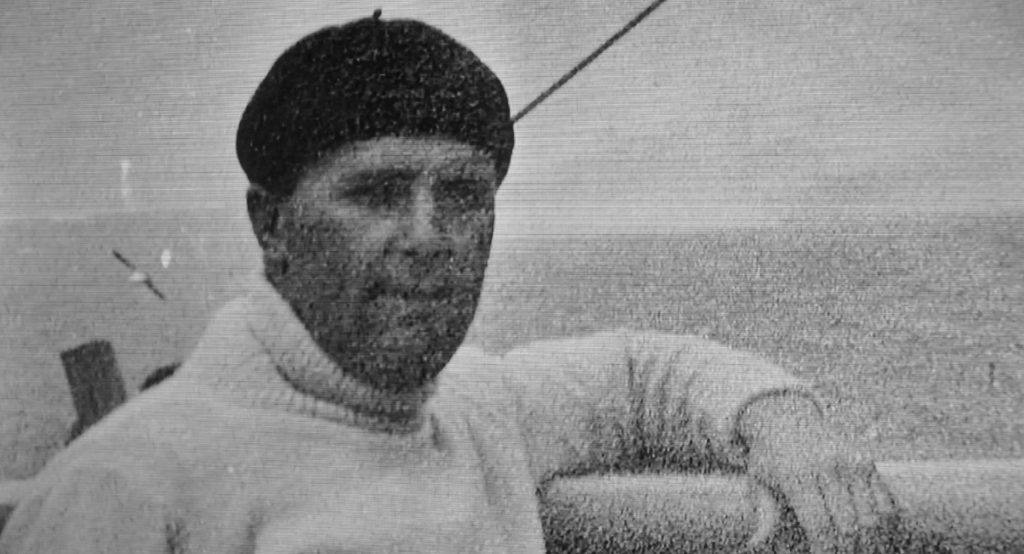

Header Photo: Jim Preece

Jim Preece – Chief Officer – John Biscoe I – 1950-53

All Photos: Jim Preece

“She was cramped alright. No comfort for us. The Master’s quarters were okay. Captain Bill “Kelly” Johnston seldom permitted me to cross his threshold. I think he was worried I might get a taste for the good life. He needn’t have worried, my good life was with the Fids”

The officer’s wardroom at HMS Pembroke, Chatham, was light and airy. An equally airy, attractive young Wren asked me at breakfast if I’d like tea or coffee. She was about to change my life.

“Would you like the Telegraph, sir?”

I thought for a second or two. I’d rather have had the News of the World but realised it didn’t fit with the surroundings.

That’s where I saw the advert for FIDS. “Chief officer required for Antarctic vessel…..” Apply to Crown Agents of the Colonies at Millbank.

Continuing from John Biscoe I page

I was attending the first post war RNR course in 1949, a complete shambles, run by people who’d had no war experience. I’d already had a very broad war experience in the merchant navy and had obtained my Extra Masters certificate. I was rather proud of that as Dad, who was Cardiff docks auditor had fought hard to stop me going to sea. He was a snob through and through. When I joined the Cardiff Naval Brigade aged 13 he was bitterly disappointed because I’d be in a rating’s uniform. We lived in a class ridden society. He disliked mining people and those in the valleys but I was already a socialist and he remained a right tory.

The interview at Crown Agents was headed by Captain Johnston, who’d had vast experience in tugs during the War, and one other rather florid looking man. He didn’t say a great deal. They were satisfied and I joined the John Biscoe 1, perched on a slipway, as Chief Officer, at Thorneycroft, Southampton in July 1950. Now, of course, it’s a television studio.

The second mate, Peter Croft, was a proper R.N. Lieutenant, a real gent, no side to him. He’d been a Naval Attache in Finland and was married to a lovely Finnish girl. Norman Brown was the Third mate and he was a lovely man too. Peter and Norman shared a cabin or was it a bunk, I forget now.

I had a cabin of my own, just long enough for the bunk and just wide enough for a sink. We didn’t mind, we were enthusiastic to experience Antarctica.

We were a crew of thirty officers and ratings, the majority were Falkland Islanders. The crew lived aft under the deck, two to a cabin, sharing communal ablutions too. Their access was pretty primitive, being a steep companionway through a hatch. If they needed another escape they had to crawl along the propellor shaft tunnel and up through the engine room. The officers’ accommodation, primitive too, was within the main deck superstructure near the galley and our wardroom.

The Fids just had to muck in best they could-it was a single mess room on the same level as the crew. Up to twenty five slept in canvas, metal framed bunks, three high. They were luckier and could access through the main superstructure.

The refit at Thorneycroft was under way when I joined. I could have just sat back and watched it all happen but I was intensely interested in this unusual little vessel. For a start she was built of wood and the hull was sheathed in greenheart for ice protection. This was a fascinating distraction in itself. I made friends over my three seasons with the various foremen. Captain Johnson spent most of the summers back home in Belfast and I cycled to the yard from my guest house in Southampton where I stayed each summer. We even had a TV set and at the close of the evening viewing the resident old colonel would stand to attention as they played God save the King, much to our embarrassment. Bit like Fawlty Towers, really.

The vessel had been built in 1944 at an American shipyard for the Royal Navy as an anti-submarine net layer called HMS Pretext and was handed over to FIDS in 1947 with a name change just before sailing south that December. One of those sailing was Dr V. Fuchs, the head of FIDS. One hundred and ninety feet and a mere thirty four feet in beam. She weighed in at 899.97 Gross registered tons. Loading took only a couple of days but I had absolutely nothing to do with it. Incredible! It was organised by Royal Mail, who were our agents. Finally, they loaded the sheep on deck from Romney Marsh followed by the Fids. We were off heading down to the Cape Verde Islands for fuel and water before going on to Montevideo for R&R. The bosun, Sorensen, and I worked on the sheep. He was a Falkland Islander and had been a shepherd in the camps and most of the sheep I thought were dead he managed to resuscitate by sticking their faces into the wind. Today we’d be prosecuted for inhumanity.

We had a routine, “Digger” Ward, the chief engineer and I. He’d been an ERA in the Royal Navy, that’s an engine room artificer, a highly trained boilermaker and fitter. He would sit down in the wardroom at eleven o’clock every day for his gin and angostura bitter. Yes, we had a nice little bar corner and I’d join him. I’d also join the engineers in the engine room quite often. I’d start the engine and do bits and pieces. It was a good crowd, we all got along well. Nosh was good too, plenty of it and Silas, the cook, was as proud as punch with his uniform cap. He’d wear it through all the worst weather. He never caved in to the elements. I was lucky too, never got sea sick unlike Bill.

Stanley was a new experience alright, but then it is to any traveller on their first visit. It and the people grew on me although I got the measure of the locals’ attitude towards the ex pats and the Governor, Miles Clifford. He disappeared back to England for a bit one year I was down and when he came back he was a ‘Sir’. He was probably the last of the fighting governors. He did a bit more than sabre rattling with our Argie friends down south and gladly called in the armed forces several times to quell disputes at our bases. In these days our remit was Deception island in the South Shetlands, where we were to do battle with the Argies, Hope Bay, where we did battle, Stonington, the Argentine Islands, Port Lockroy, my favourite, then Signy a lot and South Georgia. There was a whaling or sealing connection with almost all of them…and an Argie connection.

On occasions we’d have to read the riot act to the Argies…and they did it to us too… I remember base commander Frank Elliott giving the Argies a Note of Protest at Hope Bay; he’d become exasperated with me because I didn’t take it seriously. He’d stand in front of the Argentinian commander and from notes read out “This is a formal protest from His Britannic Majesty….you are violating article so and so” on and on he went. There’s me shaking my head. Anyone else would have said ‘Ok mate, lets go and have a drink’ after they’d read out the protest. Not him.

Bill Johnston left me to it really, once we were doing the bases. It was exciting working with the Fids. I thought he was a good Master, certainly a brilliant ship handler….most of the time! He seldom socialised but liked a gin. With few of the tools of the trade we navigated cautiously once amongst the land.

”Digger” Ward claimed he could smell ice, so we would always call upon his services when still an estimated day from ice. Of course, it was always a guess as we had no weather forecasting apparatus and minimal electronic navigation aids. Good old DR (Dead Reckoning) got us from A to B and once in the channels and passages of the peninsula we treaded cautiously with poor radar and even worse echo sounder. Safer to lower the anchor and creep along slowly feeling the bottom. We learnt to be wary of radar distances off ‘land’ because they could be distances off the ice or a berg. DF existed but there were no stations down here and seafarers still did not trust this device.

We had our share of human tragedy. I suppose it was to be expected; we were still at the frontier of Antarctic exploration. Arthur Farrant at Deception was a sad case of suicide. Just after we had arrived he shot himself through the mouth in the generator shed. He was 37 and I think this sent a message to the powers that be. Your selection process needs tightening up and consider this to be a young man’s job. He was buried in unconsecrated volcanic ash just beyond the whaler’s cemetery. I had been all for committing him to the deep but Captain Johnston sought the view of Sir Miles. The Governor held sway on all matters in FIDS. Soon after I arrived home in Cardiff I was approached by his brother and sister in law looking for reasons for his death. No one in head office had made the family at peace with their loss.

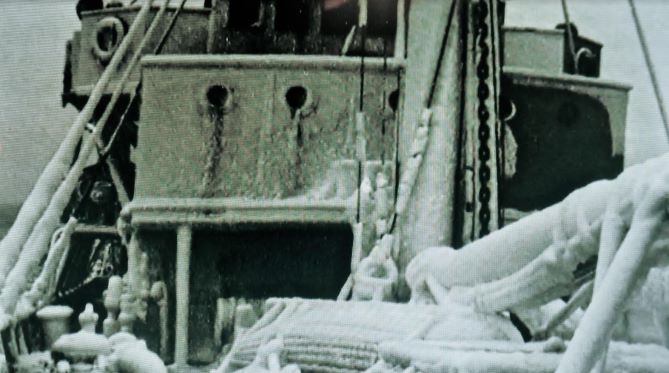

Despite being a good ship handler Captain Johnston did get into trouble with the ice occasionally. We’d get locked into bases or trapped. But his motto was to wait and eventually the wind or tide would free you up. And it did. Nonetheless, he had nerves of steel. Sometimes the crew would get itchy and go over the side for a game of football or just larking around. On one occasion we had Sir Miles Clifford on board, conditions were deteriorating, it was late in the season and he was being a real idiot about things. Johnston had to quieten him down-sharply.

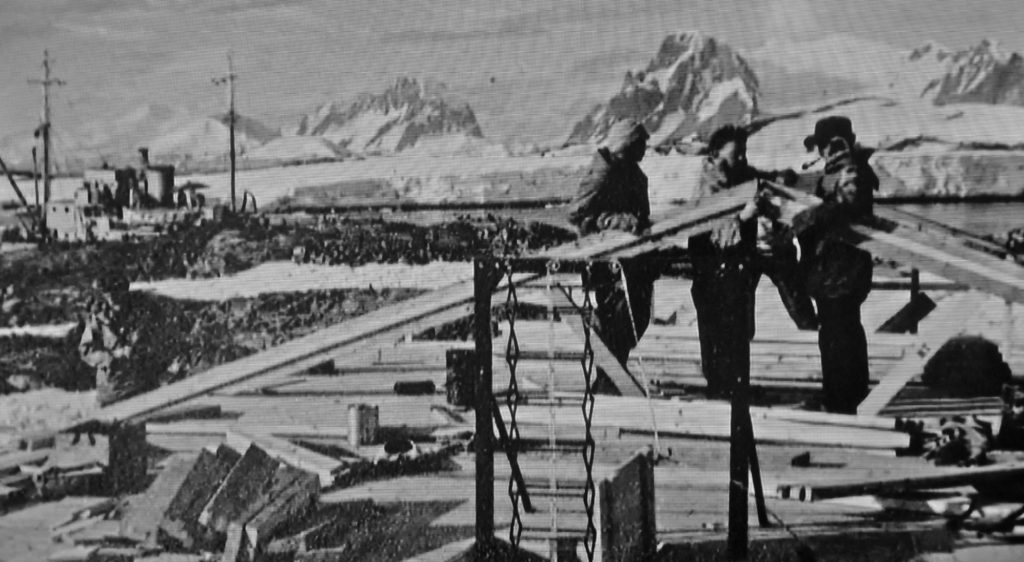

FIDS were either tight or poor, probably both but I remember we’d take cement fondu down in the ship and dig gravel from near the waterline when it came to setting up foundations. Of course, they weren’t great big floor slabs, just columns on which the base could be set up. Boulton & Paul provided a lot of our huts sections. They were actually aircraft people who got sidelined into prefabricating sectional buildings. I was keen on carpentry and would help with construction. I’ve got my name engraved in the roof section at Hope Bay in 1952. It was called Trinity House. We all got stuck in with the Fids, helping them with hut construction. It was the only way to get these essential jobs done and the camaraderie that developed was priceless. Yes, there were niggles and sometimes they came from the Fids concerning the amount of hours we would push them to work.

Construction Underway at Hope Bay

Building Hope Bay Base

Jim Preece on right

We carried a scow, which sat across the single hatch and in the scow we squeezed the tow boat. A hefty derrick straddled the hatch, so you can tell we didn’t really have a lot of space for stores and building materials. I don’t know if anyone was looking to the future, though.

Jim (L) with Chilean Officers

The bases all operated with dogs and one of our tasks was shooting seal for the bases. We would go hunting on the floes and butcher them. Getting the carcasses back aboard was the trouble. We’d tow them, often three abreast, each side of the launch and with a wire strop through their jaw we would lift them aboard ship, lay them in heaps and distribute them to the bases. A lot of the time we were ferrying dogs and sledges between bases.

Sealing was necessary. It saved FIDS money on purchasing so much pemmican for the dogs. The whaling at South Georgia was another thing. We would go there to assist the resupply of the Falkland Island Government administrative centre at King Edward Point. Across the cove a massive whaling operation was going on at Grytviken. Despite King Edward Point possessing a magistrate, police station, customs and all the trappings of civilisation it didn’t stop the wily whalers from trying to gather together materials for distilling. Alcohol was forbidden, but ingenuity prevailed and illegal stills were constructed all over the place. We would be asked for Cherry Blossom shoe polish, even. They could extract the alcohol from that, you see and a bottle of whisky or other spirit traded for many hundreds of cigarettes.

FIDS didn’t have a scientific base on South Georgia but I found enormous interest in the stations. We’d stay perhaps a week or so at a time and I made friends with many of the whaling people. I’d go to the training box where harpooners were instructed in shooting.

In Stromness Bay, which was slightly north of Cumberland Bay there were three other whaling stations, they were Leith, Husvik and Stromness. Here they had the massive factory ships like Southern Harvester, Southern Cross, all Southern something. Constant noise, smell, oh, the smell. It got into everything. The slaughter was terrible but the organisation was admirable.

At the end of the season we’d retreat in reverse order. By this time in April the weather was chasing us out and from Stanley we would head up to Montevideo, Cape Verde’s and back to Southampton. After the ship had been discharged and tidied it would be time to sign off the crew for the summer. Some might get a job locally, others would work in the holiday camps along the coast and one or two might try working on a coaster or other non union ship. Captain Johnston, when his administrative work was done, escaped back to N. Ireland and I would sign up at my guest house and join the Colonel round the television after a day’s work at Thorneycroft.

One year, yes 1953, we had to take part in the Fleet Review at the Spithead to mark the Queen’s coronation. Bill Johnston didn’t want any part of it. But he had to!

So, why did I leave Fids? Well, I joined not too bothered about getting a command. I was more interested in the adventure but began to realise that I wouldn’t be getting anywhere in Fids in a hurry. Captain Johnston wasn’t going anywhere soon. No one in the office was communicative, Johnston himself wasn’t very encouraging and I suppose I started looking elsewhere. After all, this was a one ship operation. Well, I had an offer of a chief officer’s job on a brand new cargo ship for the New Zealand line. She was to carry up to 12 passengers too and I had a cabin, dayroom and my own bathroom. How could I say no!

I always remembered Fids with a fondness. Little did I know that within a year of my leaving, Fids was to grow out of all recognition when they brought a ship they renamed Shackleton in 1955.

Jim Preece, Mate, John Biscoe I, 1950 to 1953.

Extracted and abridged from the BAOHP by Jack Tolson