Seven Happy Years – Mike Bell (October 2009)

(Mike passed away in March, 2019. This story was provided by Mike Burns, and published with the Kind Permission of Gill, Mike’s wife)

I worked as a geologist on the Antarctic Peninsula, Alexander Island and South Georgia during seven years between 1968 and 1975. My mother died recently, and carefully filed amongst her papers I found some of the letters I had sent 40 years ago. Here are a few unedited snippets from those letters together with some reminiscences to try to paint a simple picture of our fun and adventure during those happy years.

The role of BAS geologists was to produce maps and to research the origins of rocks, fossils, and minerals. Up until the 1970s the tradition of geological mapping of blank areas of the world was still strong, with political, scientific and economic justification. Each year two or three new contract geologists were recruited to work in the Antarctic. ”We have just had another salary raise — about £1400 now.” I was fortunate to have Gwynn Davies (who has just retired as a petroleum geologist and is living in Brisbane, Australia) and Ali Skinner as my companions. Our contracts normally included two winters and three summers in the Antarctic followed by a period back in the UK writing up scientific observations. All our work was published in-house, either as BAS Scientific Reports or as papers in the BAS Bulletin. We were not permitted to publish results in any other place. This was a strange rule when viewed from the present-day perspective of publishing with as much exposure to the scientific and political world as possible. Our boss, Dr Ray Adie, who edited all the work with meticulous care, later became Deputy Director under Sir Vivian Fuchs. He was the only permanent member of geological staff. I was surprised at my interview when Ray said that by a strange coincidence he had been to the same primary school and university as me in South Africa. Maybe that was why I was recruited!

We were based at Birmingham University where the first task we were set was to read a small library of books and reports on Antarctic exploration and geology. We were also issued with a cheap and primitive field kit not much different from that used by Edward Wilson. The bits I remember were a ball of string; some old fashioned, simple mapping pens (with Indian ink and metal nibs); two hammers with wooden handles (and some steel wedges to repair them when they inevitably broke); canvas bags for specimens and little card labels (but no felt-tipped marker pens); pencils and cheap notebooks; a world-war one vintage geological compass and a plain-tabling kit to draw maps. A strange quirk of Dr Adie (who was very uncommunicative) was that we were not told where we were to work. Each geologist was given a sealed brown envelope just before leaving England, only to be opened at sea. At the end of the first year you received a second set of written instructions defining the next area to be mapped. One geologist was confused when he was told to map part of the sea in Marguerite Bay with no rock outcrops. When he sent a telegram asking for confirmation of the co-ordinates the return telegram assured him that they were right.

My first morning out from Southampton I was on gash duty; this coincided with rough weather in the Bay of Biscay: “it certainly lurches around a lot; it has a rounded hull and is fairly top heavy… the poor old John Biscoe really bobs about, it is never still (at times you actually slide around in your bunk).” In the galley I was given a tray of fried eggs, slopping back and forth in a sea of oil. After a brave attempt to get them to the fiddery: “only three people for breakfast (I wasn’t one of them),” I retired to my pit where I stayed for the next two days feeling sorry for myself. We had a lazy month at sea in lovely warm weather: “everything is very informal and happy, and most days a scow is filled with water for a swimming pool the first mate (Malcolm Phelps who went on to become a long-serving and respected captain) is in charge; he is very pleasant and easy going, usually dressed in a swimming costume. . . . I’m sure there aren’t many jobs where you can have a holiday at sea on full pay.” I loved sitting on deck chipping rust and painting.

“The engines have been making a funny noise and we have stopped — about the 12th time this trip. After ramming the pilot boat, we eventually docked (in Montevideo)”. We couldn’t believe our luck to have two weeks in Uruguay when the ship went into dry dock for repairs. Four years later I wrote about Monte: “Food and drink are incredibly cheap — beer about 4p a glass and £1 for a huge meal with wine ad lib.” When we sailed after the long delay the season’s supply of potatoes had gone bad: “we spent the whole day in the hold sorting out rotten potatoes — a really horrible job — we must have thrown many tons away — liquid was just running out from under the sacks. I am pleased to say I haven’t missed a meal since two days out of England, the food is really excellent and the weather has been perfect — sunshine all the way.”

In Stanley: “the Governor’s party was rather formal — silly to bring suits 6000 miles for one hour’s wear. The governor had been to Nyasaland (Malawi) — so we had a long talk about the geology of Nyasaland — about which neither of us knew anything.” We were issued with a generous allowance of field clothing in Stanley. This included woolen battledress trousers that scratched the insides of your thighs raw when sledging, string vests that no-one wore, and warm canvas mukluks (apparently bought as an ex-Korean war job lot). “Pete Butler (now living retired in central France) had some bad luck when a bundle of letters he was carrying blew into the sea and he had to wade after them; I had a good laugh but am afraid he wasn’t very amused.”

“We should arrive at Deception about on schedule — but we don’t really know what is happening until it happens — or slightly later It is a most annoying feature of the ship not to hear the news of where you are going till you are nearly there.” “Companionship continues excellent and I am very happy. I have started growing a beard — the result so far is rather horrible (being too lazy to shave I still have it and it is still horrible). Some big swells sent the dinner flying. … Rough during the night. We continued until the captain’s bookcase fell over and then turned up into the wind at slow ahead (quite a relief!) P.S. no seasickness, hooray! . . . We took 3-1/2 days instead of 2-1/2 spending one day hove to because the deck cargo of 45-gallon drums started sliding about. “

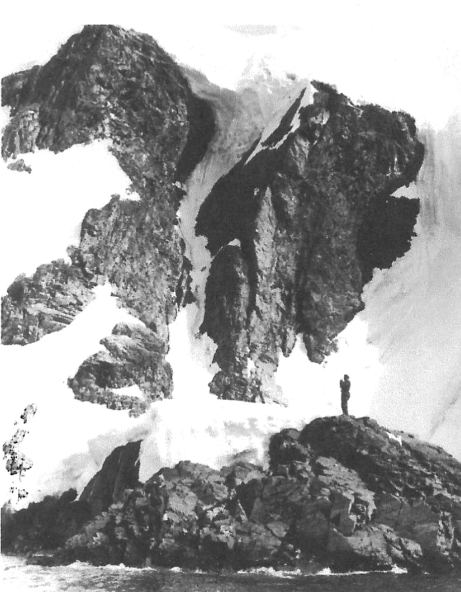

Our first job was the geological mapping of small ice-covered islands off the Antarctic Peninsula, using Gemini rubber dinghies. As a nervous young person I was thrown in at the deep end when the captain told me I had the John Biscoe at my disposal for a week and asked me what I wanted to do and where I wanted to go. “We had to stop work because a seam on the boat (the Gemini) split and leaked unless we were going forward. It is rather silly; they bought the boats second hand from the RNLI and they are in very bad condition — it seems ridiculous to try to save money like that.” For this exciting work we jumped ashore onto slippery rocks beneath overhanging ice cliffs as the boat rose and fell in the swell. After quickly hacking off a piece of rock before the ice fell on our heads we leapt back into the boat. We were: “maybe the first people to land on this island.” “The senior biologist tried to climb up the ladder to the ship holding the dinghy’s painter and was pulled off into the sea, it was quite funny we soon managed to pull him out (he is the season’s first member of the Antarctic Swimming Club)… but at the same time the painter wrapped itself round the propeller of the outboard.” “We anchored at Potters Cove for a two-day Christmas holiday — it gives the crew a break and means they can safely get drunk The Shackleton, Endurance and John Biscoe are all anchored together. In the evening we had an inter-ship carol singing (shouting) competition — we won, and it was very cold. “

“Just as I was going to bed I heard the engines starting up — apparently the new Twin Otter was down somewhere in Marguerite Bay, so we are going to look for it — great excitement on board.” We ploughed south but soon got stuck in heavy pack ice. On another occasion on the Bransfield: “It took us 5 hours just to turn round . A large iceberg came bearing down on us at about 2 knots today and only missed our stern by about 50 yards — too close for comfort. Actually, I suppose the berg was still and we in the pack-ice moved past it! The ship really shudders and jumps around when it hits the ice.” The plane had landed blind but didn’t know where it was. “There was a great laugh when the news from Stanley said that the aircraft had landed during an ‘exercise’ and that we were part of the ‘exercise’ — it shows how easy it is to distort the news without actually lying.” The plane had been completely lost in thick fog, had run out of fuel, and had landed on the western side of the Peninsula and not where they thought they were on the eastern side. Luckily by chance it came down on flat ice rather than against a mountainside. It was eventually located and saved with fuel flown in by the Endurance helicopters.

“The three months we have been on board have flown — all are very happy — no quarrels — it is wonderful to meet a crowd of people with such equable temperaments. “ Although things normally went smoothly, sometimes there were minor problems. A few years later I wrote of an amusing incident on the Bransfield: “One chap went a bit crazy since leaving Stanley . . . came in last night naked, wandered over, sat down and had a drink. So, the Doc put him to bed with a tranquilizer. “

“Although the post is a bit slow it does seem to get through. Some of the chaps have been phoning home from here (Stanley) but I think it is rather silly … I honestly wouldn’t know what to say for three minutes.” Communication from home for field parties was usually limited to letters once a year. We also had a free monthly telegram of 200 words from home and 100 words back. I don’t think I was alone in often struggling to find 100 words to say.

At Adelaide: “the base leader (Ian Willey) seems a fine sort of chap… We have been unloading cargo from 8.30 am until about 10 pm so everyone is rather tired it is amazing how well everyone works in together — mind you there is one chap who is usually taking photos when there is hard work — it doesn’t make him very popular. “

“We sailed round behind Adelaide Island (to the Rothera area, there was no base there then) to do some sealing to feed the dogs. I must admit I was dreading it, but the seals are shot in the head and die instantly — and it wasn’t anything like as bad as I had expected. … They were really stinking after 3 days. but luckily I had a bad cold, so it didn’t matter.” ” We met the Endurance off Adelaide — one of our chaps had to see their doctor. I think he is a hypochondriac — he has seen three doctors now and doesn’t believe any of them.” “Yesterday was bath day — which comes round about once every 10 days . . quite a pleasant change after cutting up rotten seals.”

I wintered with Mike Elliot, George Kistruck and Andy Wager at Fossil Bluff. We were flown in from Adelaide so that we could start work early in the spring before the dog sledges and planes arrived for the following season. Due to troubles with the planes (the Single-engined Otter had crashed, leaving only one plane) our supplies were very limited, and several boxes were off-loaded for the last flight when the plane couldn’t get off on the soft snow. Sadly, these contained most of our winter’s goodies including tins of jam, all the beer and all but two bottles of gin, so we had a very sober winter despite unsuccessful attempts to make wine from dried apricots.

“On clear days the views are wonderful — more beautiful than you could imagine and very quiet and lonely. The nearest people are about 200 miles away at Stonington (and quite unreachable until the following summer). Our communications out of here are really hopeless. Due to an unfortunate accident when a spanner was (literally) dropped in the works of the diesel generator we only have Tilley lamps and batteries charged with a petrol generator for light. . . There is a very strong temperature gradient with the floor seldom above freezing. . . . I haven’t had a bath (or even a proper wash) for four months — and little prospect of one for another six. . . . It is the small things I miss, like birds, flowers, chips, beer, and new people to talk to, fruit. . A great experience and one I wouldn’t have missed for anything.” One painful memory is popping a steel bolt into my mouth at minus 20 degrees to hold it when repairing a sledge. Our toilet was a flour tin in a frozen tent. My heart went out to the poor individuals who were recently given the task of digging up and shipping out all the waste from Fossil Bluff.

In the spring we started work at Ablation Point but became frustrated with the snow-covered rocks and bad weather. “There are many glaciated pebbles even on top of the 2000′ ridge behind the campsite. So, it looks as though the Antarctic is warming up!” “We have had 5 days of wind so very little has been done … It is strange lying for days listening to the wind howling and the tent flapping and creaking Sometimes it shakes so much you think it will disintegrate. . . . We have very old tents — it is a bit worrying when the wind blows hard — up to more than 100 knots — so noisy you have to shout and rather frightening . . . “ On another occasion when dog sledging: “we spent 10 days out of 18 ‘lying up’ ….it certainly cuts down on the amount of work you can do. Apparently the record continuous lie-up is 26 days — they must have been terribly bored!” I remember one period of several days when our only reading matter was two ancient Readers Digests and there were no batteries for the radio. It was during this time that I perfected the “Fid stare” — the ability to stare into space with the mind in neutral, which has stood me in good stead for most of my life. This is to my wife’s annoyance when I relax for hours on cramped international flights. One night my rucksack (with geological specimens in it) blew away, never to be seen again. Once, coming back in a whiteout at the end of a day’s work we struggled for ages to find our tent because it was made of white cloth (presumably made for camouflaged Arctic warfare and bought cheap by BAS). We lived on sledging rations: “the meat bar is grim stuff but not too bad with lots of curry. . The old boxes are more popular because they have bigger chocolate bars. Cooking breakfast, the thing is to be organised … then you spill the milk into your sleeping bag. I have dropped some butter on this page, so the pen isn’t writing too well. I must admit that I would never have imagined that a tin of spam could be looked forward to for a Christmas treat!”

At the beginning of September, the first dog sledges arrived from Stonington. “It was funny at first trying to find something to say. ‘Hullo’ long pause ‘have a good trip?’ long pause.” “Food is our main topic of conversation. … The rest of the world almost ceases to exist, ‘news’ is what the other sledges are doing. . . I haven’t heard world news for about 6 months now.” I remember standing outside the hut on a crystal-clear night looking up at the moon the night the astronauts landed.

Although I never had my own team I soon became a dog fanatic: “most people become a little bit ‘dog crazy’ . . . there must be a total of about 150 dogs now (at Stonington and Adelaide). . . The dogs are unbelievably keen to be going, and nine of them pulling together are immensely strong. . . . The first few miles are a bit chaotic as dogs keep stopping to lift their legs”. I discretely didn’t tell my mother they gobbled the droppings of the dogs in front, or even, as a real treat, those of people when they were presented on a spade. In the field: “each dog gulps his daily 1lb block of Nutty in about three mouthfuls then desperately plunges on his span as he waits for more. Quite often the pickets come out and chaos ensues ….I got my hand bitten by accident when I grabbed a dog’s neck at exactly the same moment as another one decided to attack him.” The scar is still there.

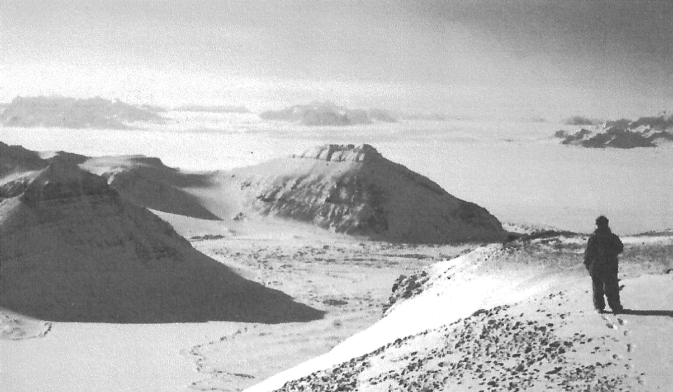

“It is a wonderful feeling to look out over vast areas where no one has been before. We were the first to go up Grotto Glacier — so are really very lucky.” Lots of bad weather and soft snow meant very hard work with sometimes a distance of miles in a day. On one occasion we: “averaged five miles a day for about 10 days, it was very hard work and a little depressing. . . For days the snow was about two foot deep, at times thigh deep.” The following year in very different conditions we covered more than 50 miles in a single day as we sledged over crisp hard surfaces in northern Alexander Island. “Two days took us across to Staccato Heights a previously unvisited range of nunataks” (my spell-check doesn’t like this word and suggests lunatics) — we were surprised to find they were NW-SE rather than N-S on the map.

They are very impressive, rising straight up from the ice for several thousand feet.

The weather has been awful, and we have just arrived back after seeing virtually nothing for three weeks.” I didn’t tell my parents that I had fallen down a crevasse on Beethoven Peninsula when the bridge gave way as we crossed with our sledge. Fortunately, part of the bridge went down with me and wedged as the hole narrowed down. I was rescued from a rope’s length down by Mike Burns and Tony Bushell but one of my skis went on down to the bottom and was never seen again”. Health and safety regulations had yet to take hold. Sir Vivian Fuchs gave a standard lecture at the annual Cambridge conference for new Fids where he told us of the death toll of the previous years, which at that time averaged one a year, but at no time did we have any classes on how to get out of a crevasse or were told not to camp on sea ice. Safety relied on common sense and experience. It was common for geologists to spent long days working completely alone far from contact with their companions.

Back at Fossil Bluff: “an amateur dentists’ shop was set up to try to fill a rotten tooth great fun trying to get the right proportions of mercury and metal so that it did not set instantly! Eventually it was in and apparently a great improvement — the dentist was Shaun Norman — the Stonington base leader and a very fine person. During the winter he did an operation on a dog — by radio correspondence — unluckily it died.” “We are looking forward to the planes now, due in a month or so, and hoping that they bring the mail. … You have no idea how much we look forward to getting the post.” “Some things end up in Argentina, then the Falkland Islands address is frantically scratched out and ‘Islas Malvinas, Argentina’ is written all over them, and they are delayed for months.” This was 10 years before the Falklands war.

“The Biscoe was supposed to go north to fetch . . Fuchs and some of his cronies but it was held up for about a month by heavy pack ice, so the plane had to fly up to Argentine Islands to bring them all down, without Fuchs fortunately – for once the bad weather has been in our favour. “

At Adelaide: “as the snow melts lots of rubbish appears which has to cleared up.” In the days before environmental concerns this meant being thrown in the sea; along with all the base gash, sewage and hundreds of 45-gallon fuel barrels. “The base rubbish is thrown off the jetty — at the moment it just lies on the ice, so every now and then we have a great bonfire. Stonington was a real mess in the summer — it has been occupied for almost 20 years and . . the whole of the small island is like a great rubbish dump with an overwhelming smell of age-old rotten seal — a nasty contrast after Alexander Island — about 3 months without a trace of man. “

Two of us were lucky enough to win a draw for two weeks on the Endurance to show them how to do sealing for dog food. “We only got 20 seals because the captain changed his mind when he saw the blood.” “The Biscoe .. went round to the fiords east of Adelaide and caught about 150 in a day.” “When the Endurance came back we had a film show on board and one of the air mechanics had too much to drink, when we got back to base it was pitch dark at the jetty and water was flowing over the top of it so you couldn’t see where it ended — instead of landing on shore he jumped straight into the sea carrying an autographed photo of the Endurance that the captain had just presented! Needless to say, the picture disappeared” . (SEE MORE OF THIS). “Unloading at Adelaide was chaotic with heavy swells and ice bergs and brash around the jetty — a miracle no one was hurt. The worst part was getting the fuel ashore — it came in bulk tanks to ‘facilitate handling’, instead of half a day took 4 days to get ashore! “

“The generators are very poor and can only supply about a quarter of the power needed — so they are a good subject to complain about to London — all the heaters in the new huts are electric but have never been used.” We were told we could either have new generators or a new genny shed. Neither option much use really as the new generators wouldn’t fit in the old shed. “I am becoming quite efficient with a sewing machine…. we have one new tent but lately they have been made by a new firm last year they were used for the first time at Stonington and one of them sort of blew to pieces….all the seams have to re-sewn and the poles replaced with ones from an old tent.” “One of the muskegs caught fire .. used up virtually all the firefighting equipment . . you can’t use foam extinguishers at low temperature and because it was windy all the gas and powder just blew away .. no-one knows if it was put out or just went out, the cab was completely gutted.” “One job which isn’t much fun is chopping up seals, they are a year old, rotten and smelly but the dogs don’t seem to mind.” “We have had penguins to eat (illegal), it is very good dark meat, a really good change from tinned meat….The curious penguins drive the dogs mad and of course some of them get just that little bit too close.”

In the spring we sledged over to Stonington, and then set off on a one month’s journey down to Fossil Bluff. The sea ice in Marguerite Bay had become too unpredictable to trust and the route overland across the plateau included a great struggle with days of relaying a mammoth 3 tons of boxes of food and kit 50 1b at a time up to the top of Sodabread Slope (originally called Sodomy Slope by the British Graham Land Expedition who apparently thought the term too rude for their genteel readers of the 1930s) at about 4,000 feet. “As we were setting off next morning Mick’s dogs decided to go back down the hill, together with a fully loaded sledge. They went charging down the hill at high speed and I thought we had seen the last of them, but Mick (Pawley) managed to turn the sledge over just before the really steep bit.” We crossed the Wordie Ice Shelf some years before it broke up, probably as a result of global warming, and a week later went down the South Chapman Glacier to George VI Sound, about 4,000 feet in 10 miles: “a magnificent route . . great walls of rock and ice. . . . Ending with a very steep hill, which I finished sliding down on my face. .. At the bottom we ran into a mass of crevasses which were rather nerve wracking . . . with dogs dangling by their traces — they get really nervous.”

The break-up of the massive Wilkins Ice Shelf linking Charcot Island to Alexander Island was in the news in 2008. Forty years ago, as the first people to travel on this shelf, I wrote: “We discovered a group of very small islands in the Wilkins Ice Shelf which aren’t on the map, it was quite exciting.” We also corrected maps made from air photos which showed large features as much as 15 km out of place – a far cry from the present-day centimetres of GPS. The sense of geographical and geological exploration provided a strong motivation for the field parties. As the first visitors to nunataks on the Beethoven Peninsula I was excited to discover evidence of recent sub-glacial volcanic activity.

“It has been a very good summer, a fine end to two very happy years here — apart from seeing you I have no wish to leave.” My best memories of the return from months in the field are the smell of bread and oranges and the sound of the sea and birds. Thoughts on getting home included: “Apparently long hair is fashionable now which means that I’ll be out of fashion as usual. It’s going to be hard getting used to paying for food again, no more half inch layers of butter.”

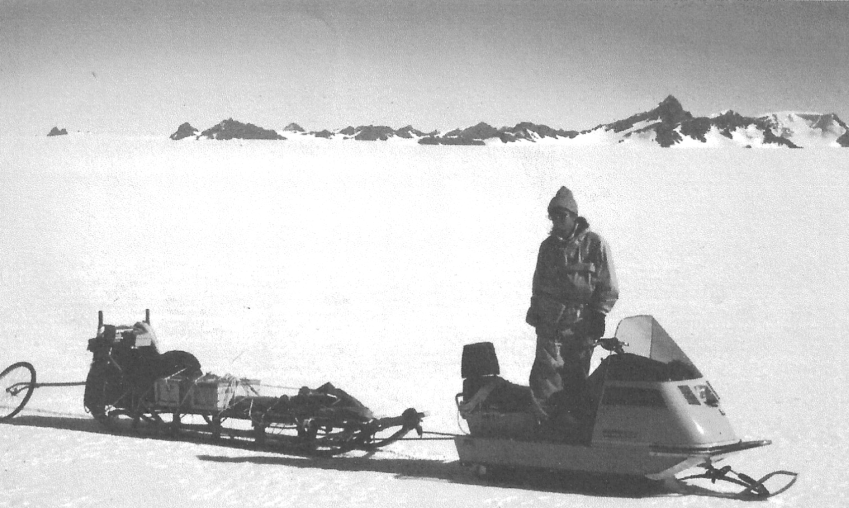

A year later in 1972, I went south again for a plane and skidoo-supported summer in southern Alexander Island: “all is much as it was before with an overall smell of seal and dirty dogs.” “The skidoos go well and are very efficient, but you certainly miss the companionship, trials and tribulations which go with the dogs.” Very sadly the successful use of skidoos this summer helped to speed the end of the dog-sledging era.

“I am going to spend the next few weeks with Chris Edwards — a quiet Scottish chap who is quite cheerful — despite a Lilo which lets him down each night. He’s trying to patch it at the moment — such trivialities become major issues down here; the repair kit says, get cycle repair glue from your nearest cycle shop!”

My final season was six-months mapping the spectacular mountains and fiords on the south coast of South Georgia. The geology on this island is a rare section of sea floor rocks. I was lucky enough to have as my companions the bright youngsters Bryan Storey (now director of the New Zealand Antarctic scientific survey) and Bruce Mair who took me under their wing and taught me about the plate tectonics revolution which had passed me by in the years of my geological isolation. Our GA Dave Orchard complemented a great team. He managed to bake excellent bread in a homemade flour-tin oven in the tent (never mind the large doses of carbon monoxide), in between dossing, hidden in carefully built rock shelters. He delighted in telling a story of loading heavy rocks into an unpopular geologist’s rucksack for the long journey back from a day in the field. An interesting point in these days of instant worldwide communication was that we had no radio in the field. A low point for me on South Georgia was the dreaded ‘Ching’ (dear john) letter; but it was well deserved after the self-indulgent enjoyment of the previous 6 years. We got no leave on return from field work: “I am trying to think of a polite way to tell Adie that I intend to take some time off to go home” .

My experiences in the early 1970s marked the end of a way of working which had been successful (if at times a little dangerous and inefficient) since the groundbreaking British Graham Land Expedition of the 1930s. I wrote: “There aren’t going to be any more wintering geologists, only summer trips. Also, they have closed Stonington and are going to get rid of most of the dogs — it’s rather sad really. I suppose we have seen the end of an era”

Thanks to the many friends whose warm companionship made it such a wonderful experience.

Mike Bell – Geologist – Fossil Bluff 1969, Adelaide 1970

I enjoyed reading Mike’s Seven Happy Years story, including the embarrassing loss of the presentation Endurance photo in the icy water off the Adelaide jetty.

I think I may have a photo of one of the marine biologists in full scuba gear by the jetty looking for the signed and framed photo shortly afterwards?

I have never forgotten the event, but could not remember what visiting ship we had been on until I read the story yesterday, so thanks very much for clearing up the mystery!

Cheers

Rob.

Great to read Mike’s Seven Happy Years anecdotes , they brought back many happy memories for me and his first reactions to seal chop exactly mirrored mine .

I still have a collection of fossils from the Bluff which I collected on an enforced stop -over . Mike told me all about samples and kindly offered to bring them home along with his own in his geology samples box . They would have been far too heavy for me to bring home in my airctaft luggage !. Mike had the rocks ready to collect at Bermingham Uni. When I went to see him during a BAS Club reunion . 1975 ?.

A lovely read, All the best Dave R.