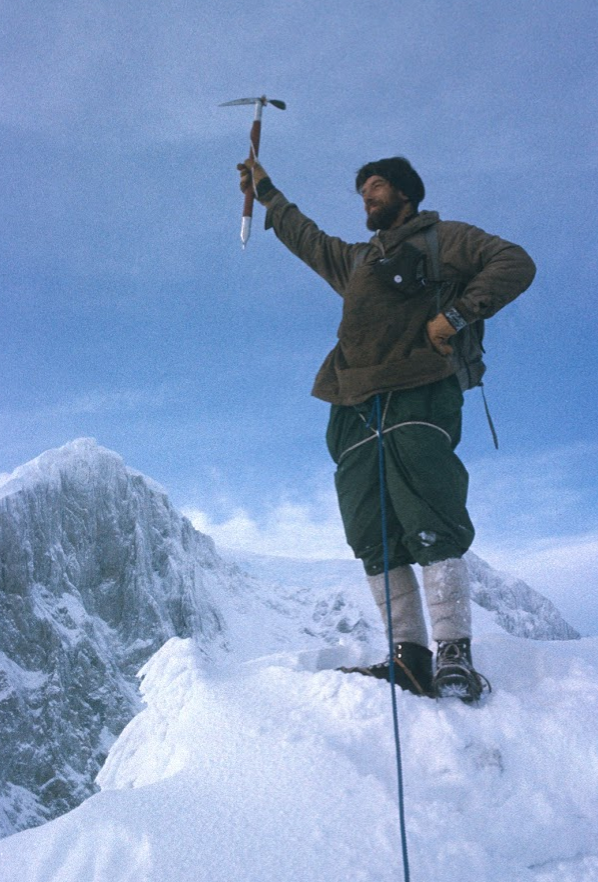

(Header Photo: Dave Rinning)

Adelaide Island, some 80 miles long and 10 to 15 miles broad, lies off the west coast of Grahamland, a few degrees inside the Antarctic Circle. The base sits on a rocky promontory at the southern extremity, a hotch-potch of multicoloured huts, lining the Hig14h Street from the jetty to Hampton House, the main living quarters. And dominating the depressing scene, the 80-foot ‘Eiger’ topped by the meteorologists’ hut, spouting, at intervals, weather balloons and drunken ‘met’ men toppling down the south face on to the bunkroom roof.

From base and the 150-foot ice cliffs on either side, the Fuchs Ice piedmont slopes gradually up past the aircraft landing area to the mountains which dominate the east side of the island through-out its length, the piedmont on the west providing a conveniently safe approach to the hills on that flank. The mountains themselves are certainly as large as any in Grahamland, despite their absolute altitude at least as large as the average Alpine peak, and their sprawling vastness and complexity makes them all the more interesting. Most of the main mountain tops in the southern half of the island had already been climbed: Mt. Ditte, Mt. Liotard, Mt. Mangin, Mt. Barre and Mt. Gaudry – the highest and most impressive at 9190 feet, rising 7000 feet in one sweep from the piedmont. Beyond those, the chain was split by the vast Shambles Glacier, some 8 miles wide, draining the piedmont to the east, and to the north again stood Mt. Bouvier, unclimbed and almost untouched, perhaps 8000 feet, and second only to Mt. Gaudry. The main north-south ridge of the Bouvier Massif, harbouring several tops and numerous glaciers, was supported on the southwest by the Snake Ridge rising in one graceful curve of over 5000 feet from the piedmont to the sharp summit cone of the highest top. This was the mountain and the route on which I had set my heart.

The only previous attempt on the mountain by this route, of which I knew, was one by Davie Todd and Jimmy Gardner back in ’65, and this was thwarted by the weather within a couple of hours of their starting. This, in fact, was the main problem in considering climbing at all on Adelaide. The only predictable fact concerning the weather was that it would be 99% grim, as sure as fate. Even Glencoe has nothing on Adelaide, so that’s quite something….From this one can only assume two things: that in the northern hemisphere, all bad weather converges on and funnels through Glencoe, before spreading out across Scotland and the rest of Europe, and all bad weather in the South Pacific and the Antarctic Ocean converges on Adelaide before diffusing across the peninsula and the rest of Antarctica.

Then comes the Spring, late September, with the daylight hours spinning out fast.

‘Be ready to leave in two weeks,’ says Mike the geologist. ‘We’re heading north to work around Mt. Bouvier till the middle of November’ I welcomed the opportunity to get out in the field at last, for although we had already been out for several short trips of a week or so, the poor weather had virtually confined us to the base.

After three weeks of the winter’s worst, the wind dropped on the 8th of October. Mike and I loaded our sledges, nipped up to the dog spans and set off north with wary glances at the still threatening sky. We made barely 7 miles. For 4 days the temperatures and the wind sored sky high, a blistering plus 11OC, a local record with gusts of 120 m.p.h. Great mounds of slush threatened to crush the tent and engulf us. The canvas cracked whip-like and a rip widened in the outer tent. We travelled north very slowly, despite taking every opportunity with each lull in the weather, and it was 11 days before we set up camp at the foot of Mt. Bouvier at 2500 feet, some 50 miles north of Base.

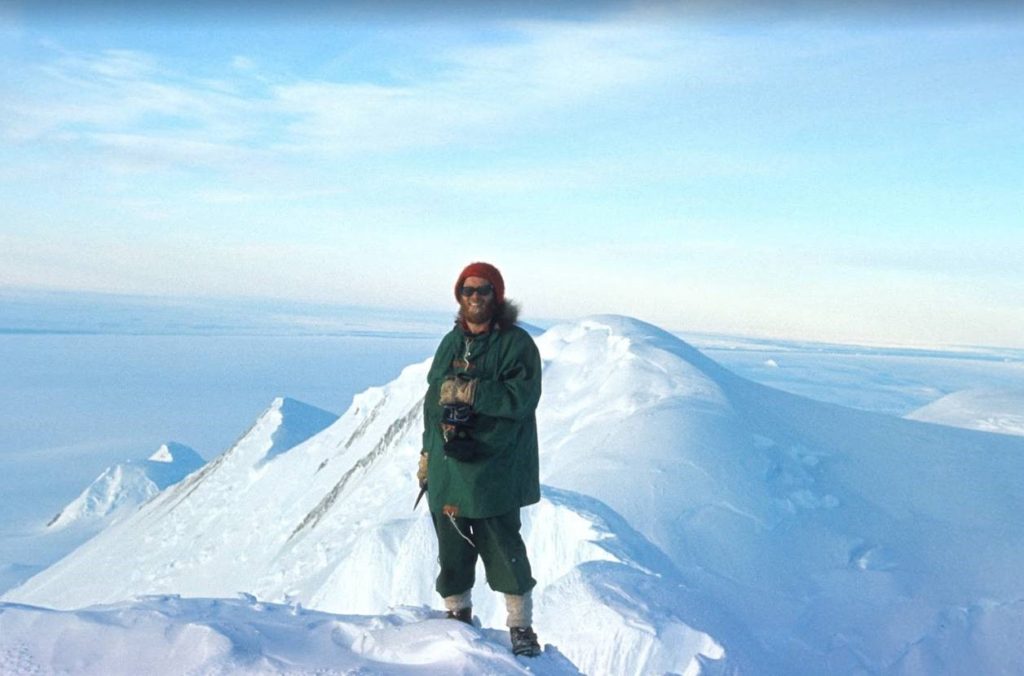

At the beginning of November, Dave Rinning, our tractor mechanic, was due out in the Muskeg with more food supplies for us. Dave and I planned to attempt to climb Bouvier at the earliest opportunity. Meanwhile, with three weeks to go till then, I persuaded Mike, who wasn’t particularly interested in climbing, and whose prime concern appeared to be to fill rucksacks and boxes with huge boulders, into climbing Bouvier South. The peak, one of the subsidiaries of Mt. Bouvier, stood at the south end of the main ridge, its 2000-foot west face bearing a remarkable resemblance to the north face of the Eiger. We took the dogs up an impressive glacier and a broad ramp onto an ice platform at the top of a 2000-foot cliff overlooking the piedmont, then, leaving the dogs and the sledge staked out on the platform, we climbed the peak by its south-west ridge. It was one of the climbs up an impressive peak which turned out to be surprisingly easy. At every turn, each apparently impossible step, each a barrier, was outflanked with absolutely no difficulty, and after a long traverse under a line of teetering seracs, we emerged on the ridge directly below the summit, a perfect dome-like arête. Mike’s altimeter registered 6800 feet, but I was inclined to be skeptical. The view was quite incredible: across the frozen fiords to Grahamland, a myriad of unclimbed peaks from one horizon to the other, backed by the ice plateau, and to the south, the mountains of Alexander Island, 150 miles away but still quite clear. Uncharacteristically, and despite the fact that this was Mike’s first climb, everything went according to schedule, even the faithful weather (which manked in by the time we got back to camp).

In these three weeks waiting for Dave to appear in the Muskeg, only two days could have been remotely described as good. Mike took full advantage of the rare opportunities, collecting rock specimens, while I snooped around the foot of Bouvier eyeing up the Snake Ridge. One evening I took the dogs north from camp, 2 miles, and up on to the first platform of the Snake Ridge, staked them out, and wandered up 1500 feet of the ridge leading to the summit of a 4500-foot peak, Sneak Peak, in the lower part of the ridge. From there, I could see that although the south side of the ridge fell away 2000 feet directly to the piedmont, there was a broad basin on the north side, sloping comparatively gently up to within 300 feet of the col which separated the peak on which I stood from the upper part of the Snake Ridge. This, I thought, would be the best route for us. We should be able to take the dogs right up to the basin just below the col, and completely eliminate that lower part of the ridge I had just climbed.

At the end of the three weeks, I began to wonder if Dave’s arrival could coincide with even so much as a day of good weather. Then three days after he was due, I opened the tent flap and looked out—eight-eighths baby blue, cold, clear, calm, sunny, perfect—freakish, but still no sign of the muskeg. What now? This might be my only opportunity for weeks to come. No, I couldn’t afford to wait. I decided to go it alone. I harnessed up the dogs and headed over to the foot of Snake Ridge, where I dropped Mike for a day’s geology. Then ‘UP DOGS HUIT’ (note 3) and off up a long slope over a series of well-bridged 20-foot crevasses into the basin, the Pit o’ Hell, at the foot of Mt. Bouvier’s 4000-foot west face, a sheet of glassy ice, criss-crossed with an intricate mesh of crevasses, and soaring up finally in the 1000-foot summit rocks. The dogs pulled well up the long slope towards the col below Sneak Peak, where I staked them out. Skis on, over the bergschrund, then crampons to the col. I stood on a rise above the col and stared at muskeg tracks 2000 feet below. Dave must have arrived only minutes after I had left. I looked up the ridge. The summit seemed so near. But I knew I owed it to Dave to go down again and return for another attempt with him. I refused to admit to myself that I was extremely apprehensive about making an attempt on such a big mountain on my own. Climbing solo on rock is one thing but climbing solo in crevassed country is quite another. I had known from the start that although I reckoned the route comparatively safe, the risk to which I intended to expose myself was considerable. I went back down with the dogs.

I was just in time. The dogs charged into the new camp at the foot of Snake Ridge. Dave and Ian were on the point of leaving to follow me up the ridge over Sneak Peak. Ian Willey from Newcastle was one of the ‘Met’ men out from base for a few days’ holiday. Although neither of them had done any climbing before they came to Antarctica, I had, by then, climbed with both of them in the southern mountains of Adelaide, and they were already sufficiently well versed in the basics of snow and ice climbing. Oddly enough Dave was a Currie man, with the makings of a Currie hardman. And now Ian was quite keen to join Dave and I on the climb. We decided to give the dogs and hour’s rest and get some food inside us before setting off again. I found it very hard to believe that the weather still looked settled.

Although the sun still set for a few hours at night, there was now sufficient twilight to enable us to consider climbing right through the night if necessary. It was the middle of the afternoon before we got away, one riding the sledge, the other two jogging along behind, shouting at the dogs. ‘PULL AWAY! PULL AWAY, COUNT! OUK! OUK! RRRRRRR-AH! (note 4) C’MON, PULL AWAY! WHAT D’YUH THINK THIS IS—A PICNIC, HUH!’

Although the air temperature was well below zero, perhaps as low as minus 15oC, the vicious heat of the afternoon sun, mirrored into the Pit o’ Hell by the west face of Mt. Bouvier, had turned the snow into porridge. We wallowed knee-deep up towards the col, but I was not unduly concerned. I already knew that the conditions on the ridge were almost perfect. We left the dogs at the same spot, strapped on crampons, and within a matter of minutes, had climbed up to the col and passed the point which I had reached earlier that day. The ridge rose gently at first, undulating and quite broad, but crevassed, then gradually swept up more steeply, almost merging with the west face, to the rocks abutting the main south ridge. But this was not to be Ian’s day. The ridge gulped and swallowed him up to his armpits in a crevasse. He took all these little trials and tribulations quite nonchalantly. His brow was wrinkled, and his face bore an almost hurt expression, as if someone had offended him, when Dave and I hauled him out.

We climbed on up towards the rocks looming large above, front-pointing as the angle increased. The surface was absolutely perfect, crisp snow-ice. Immediately above the rocks, an icefall spilled over the south ridge and jagged line of seracs cut off all hope of an exit on the right, but to the left there appeared to be several possibilities although the ice reared up to quite a high angel. At the foot of the rocks, I uncoiled the rope and opening it out to its full 300 feet, set off up to the left. The rocks were on a much larger scale than anything I had expected, a row of granite pinnacles reaching up 500 feet to the south ridge. Although I had to cross patches of bare glassy ice at the high angel, I encountered no appreciable difficulty and Dave and Ian followed hand over hand up the rope, which I fixed.

Standing on the crest of the ridge, with the view opening south and east over Grahamland, we could see the rest of the route to the summit quite clearly. By following the extreme left edge of the icefall where it toppled over the west face, we should reach, in a few hundred yards, the main obstacle of the upper section, a 300-foot step in the ridge which, from this angel at least, looked ferociously steep.

The altitude and the sudden strain after the winter’s inactivity were already beginning to take effect. Our stops became more frequent. We sprawled on the snow in a variety of careless contortions. Dave threatened to puke all over the mountain. Ian wailed and said he was finished. I had hallucinations and kept imagining a fourth member of our party. All the classic symptoms!

The route through the icefall we found with little difficulty, hopping crevasses and balancing on ragged edges, spikes rasping on sheets of glassy ice. Then the steep step on the ridge stood before us. On the left the cliffs of the summit ridge dropped away abruptly from a series of slender pinnacles, and further to the right, a huge cap of ice overhung a broad bergschrund. There was no outflanking this obstacle. In the last 1000 feet or so, the surface of the snow had changed considerably, and it became apparent that the continued effect of the sun and storm, hoar frost, blowing snow and wind, had covered the entire surface with millions of hard icy projections, so hard in fact, that even on the steepest part, I found myself relying not so much on the front points of my crampons, as on these projections, which I selected and used almost as if I were climbing on rock. Dave and Ian followed once again hand over hand up the fixed rope.

Although we now stood above all the main difficulties, the summit still seemed depressingly far away. The sun, showing weakly through a bank of cirrus on the southern horizon, had little heat. The temperature dropped abruptly and a breeze spring up from the north. We were glad of our heavy sledging anoraks and our mitts. ‘I’m going to puke any minute now!’ says Dave. But he didn’t. We unroped and dropped everything except our cameras. We at least retained our desire to record every step of the way in minute detail. The camera is the status symbol of the ‘fid’ (note 5).

Without a camera, a fid is not a fid, he is a nonentity. The ‘superfid’ on the other hand possesses many cameras, a movie perhaps, an array of lenses, a tripod, a flash gun and enough film to keep most professional photographers going for a lifetime, and all this he must constantly display like a string of expensive beads round his neck. The summit ridge now rose in a frustrating series of ice bosses and sharp arêtes. The drop down the west face was impressive with enormous accumulations of hoar frost clinging to the summit rocks, often more than 50 feet long, pointing down into the Pit o’ Hell and carved into funnels, flutes and pipes by the wind.

Then at last there was the summit, 50 yards along the ridge and a short rise. My breath came in short gasps, rasping in my throat with the last dash to the top. My heart pounded and I really did feel quite elated; or was it the thought of that cup of tea? We had promised ourselves a cup each from the flask in Ian’s pocket, as soon as we reached the top, but not till then.

It was very cold, and we lingered only to take a few photos. The sun, now very low, cast a purple light across the whole of Grahamland/Adelaide from one end to the other spread beneath us. Even the 150-foot ice cliffs of ice shelves in the fiords, appeared completely insignificant. A magnificent view.

‘I’m definitely going to puke any second now!’ says Dave again.

‘Oh well, just give me plenty warning and I’ll get my camera focussed.’

We set off down. I kept my distance from Dave. Apart from his complaint, both of us seemed fit enough, but Ian felt very tired. I warned him not to let his concentration lapse for an instant and to keep his feet well apart, waddling duck-wise. A fall here would almost certainly be fatal, either west down the summit cliffs or east down open ice slopes into areas of huge crevasses.

Ian and Dave abseiled down the steep step in the ridge and I followed. Then we struck off again through the icefall, this time unroped, which struck me as being safer than moving together roped.

It was on the very edge of the west face, whilst leaping a crevasse, that Ian fell. The points of the crampon on his right foot seemed to turn sideways as he stepped on a glass hard patch of ice, and he slipped off the ridge. The slope dropped away sharply at first, some 70o for 100 feet, then eased gradually to 50o falling at that angel for over 3000 feet into the Pit o’ Hell. ‘Oh no, oh no!’ I whimpered, helpless and blaming myself for his fate, then ‘Brake, Ian, brake!’ He’ll drop his axe, he’s sure to. I had forgotten that I’d advised him to wear the wrist strap despite the apparent inconvenience. 100, 200 feet he fell, bounding and leaping like a barrel in the rapids, head over heels, rolling sideways, then somersaults. He couldn’t possibly survive, then miraculously he was in the braking position, and he ground to a halt 300 feet below us. And then the classical irony.

Dave and I, still shaking from shock, had sped through the icefall, then Dave set off down the ice slope beside the rocks of the Snake Ridge, while I stood back from the edge and started to coil the rope which I’d been dragging behind me. I was taking up coils with my left hand. Suddenly, with this increased weight, the snow surface below me collapsed, and I was swallowed up to my waist in a crevasse. I hauled myself out and struggled and cursed with a granny knot of a rope for 10 minutes. Meanwhile Ian had traversed across the face to join Dave. I tossed the rope over onto my back and raced down after them.

‘Hey, that was a pretty nasty fall, eh?’ I said.

‘Saved me 300 feet.’

‘Are you blooded at all, Ian?’

He pulled out his shirt and revealed a huge blue bruise, oozing blood, two ribs standing out black in the middle.

‘I’ve bashed my ankle and my wrist, but they’re not too bad either. I should be able to manage down without any help.’

(Ian recalls that his key recollections, when he caught a crampon and fell off the ridge were:

“thank goodness my ice axe is attached to my wrist” and

“how do I get off my back and onto my belly to get some weight onto my ice axe to slow my descent”

Thanks to Bugs for his training, I was eventually able to stop my descent and get back on the ridge to finish the descent with nothing seriously wrong.

One thing for sure, the fall ensured my future climbing ambitions were reduced to a more realistic status. Earlier in the year Bugs and I had climbed Mount Ditte without any problems, which had given me an inflated confidence in my own ability).

We took it pretty easy on the way back down to the col. The sun, now dancing on the horizon, cast an eerie glow over the mountains. Far below us in deep shadow, the barks of distance dogs sounded. ‘Sounds as though there’s a dog off.’ The barking increased and the black specks milled round the sledge.

‘Hey, a fight!’

But we could do nothing. Normally there would have been somebody close by to wade in and stop the fight. For they are really vicious with each other when they fight. One dog or another invariably ends up with a few nasty gashes. This was no exception. Bran had taken a hunk out of Yuri’s foreleg, and he was hobbling about on the other three legs.

We all jumped on to the sledge, letting Yuri run behind, and the rest of the dogs, excited and starving after their long vigil, charged frantically down the slope, trailing saliva, legs spinning, tails bobbing, tongues flopping, dragging arthritic old Dizzy along by his harness.

My Friend Ian Willey – Dave Rowley

From our first night on Base, we just hit it off. I knew Geordies from my merchant navy days, another area in which they thrived. He ruled with an iron hand, gloved in velvet .

On the day after our arrival at base T, me and Ian had a discussion about the forthcoming flying season. The first thing he asked was “Who’s in charge”? I replied “You are”. He physically relaxed like a bag of peas. The rest is history.

Our friendship continued until his death. After BAS, and long after, he went on to become a pharmaceutical rep. for a well known Swiss company, where he and Betsy lived for many years in Geneva, but before that, and from the year that I left BAS, we met regularly in the Newcastle area.

Ian and Betsy were engaged and she and her scatty sister Fran, with me, and my new wife Delyse, would go on mad hair raising drives on a whim all over the place in a day, like Newcastle to Berwick-on-Tweed and back after a boozie lunch!

It goes without saying, that our reminiscences with Lew. and Ian at the many reunions will be sorely missed. He was one of the most positive people that I ever met.

I have a grip of Ian somewhere on the MB 2000 cruise, drawing heavily on a fag on the MV’ Orlova under a sign writ large saying “Strictly No Smoking”.

To our regret, me and my wife have missed the chance to visit Ian and Betsy in the west of Ireland, but Betsy has left the invitation open. We will get there!

Dave Rowley – Pilot – BAS Air Unit – 1968 to 1973

Bugs McKeith

Bugs McKeith was later killed while climbing in Canada – read on:

Bugs McKeith death 1978 as reported in American Alpine Club accident report

Falling Off a Cornice, Alberta, Rocky Mountains, Mt. Assiniboine

FALLING OFF A CORNICE

Alberta, Rocky Mountains, Mt. Assiniboine

Alister (Bugs) McKeith and two companions were climbing the north face of Mt. Assiniboine on 17 June 1978. About 1500 hours, McKeith went on alone toward the summit in blowing snow with intermittent visibility, while his companions belayed up the final steep section. When they reached the ridge, they found McKeith’s tracks ending where a cornice had broken off. He had fallen down the 750-meter east face, and his body was found at the foot three days later. (Source: T. Auger)

Analysis

McKeith was a very experienced climber, but had made a classic mistake. (Source: T. Auger)

Alistair ‘Bugs’ McKeith -, Alistair (1945-1978) known as Bugs (from internet)

Bugs is probably best known for his pioneering role in the development of Canadian ice-climbing, but he started off life as one of a small but influential band of Edinburgh-born climbers of the 60s known collectively as ‘The Squirrels’. His pre-Canada climbing record is impressive: new summer lines in Scotland, early repeats in the Alps as well as new routes in the Dolomites and Mont Blanc and participation of the first ascent of the North Pillar of the Eiger in 1970. McKeith’s climbing career took a brief rest after this when he joined the British Antarctic Survey, but he put the time to good use to experiment with ice-climbing techniques – a factor which would lead to his innovative and bold approach in North America shortly afterwards. After travelling and climbing in the Andes and back in the European Alps he returned to Scotland, he became dissatisfied with the ‘smallness’ of the place and moved to Canada. From the early 1970s onwards, McKeith was one of the driving forces behind the development of Canadian ice climbing, importing Scottish know-how to a largely unexploited arena and unsuspecting local climbing community. The first ascent of Tatakakken Falls was futuristic in the extreme; a thousand feet of Scottish Grade VI ice it was the hardest icefall climbed at the time and the first at its grade. McKeith also made the first ascent of the famous Weeping Wall, off the Jasper-Banff highway. Innovative aid was employed during this ascent, the crux being overcome by the use of etriers hung from Terrordactyl ice axes– a technique which emphasised McKeith’s technical aptitude and willingness to think creatively. With his period of greatest achievement probably still to come, McKeith suffered an untimely death at the age of 33 when he was caught in a cornice collapse while descending Assiniboine having completed a major face climb. What he had helped start in western Canada, however, was to evolve into a major facet of world climbing activity.

Standout climbs: 1st British ascent of North America Wall, Yosemite, USA, 1971; 1st winter ascent North Face of Mount Stanley, Canada 1973; 1st ascent Tatakakken Falls (Grade VI), Weeping Wall (V/VI), Canada.

Postscripts (Bill Taylor):

Bugs had a daughter named Arran, born in 1978, the year of his death.

His ashes were brought back to Scotland and scattered beneath a cairn built on the hillside above what is now the ruined Bothy called the Squirrel’s Drey, and the Squirrels being the Edinburgh-based climbing group, of which Bugs was prominent member.