Header Photo: Triune Peaks (Photo: Ian Curphey)

My Southern Journey (continued)

The techniques devised by the stalwarts of the Golden Age of polar travel had been improved upon over the passage of time, fortunately without abandoning the essential purity and simplicity of travelling with dogs. The actual practices we employed were almost identical to those devised by the British Graham Land Expedition of 1934 to 1937, led by John Rymill, and anyone interested in this type of human endeavour would be well advised to read “Southern Lights” , by the said John Rymill and his fellow expedition member A. Stevenson.

As things turned out, I was destined by good luck and bad, to almost replicate their great Southern Journey, a privilege that I can never get out of my mind.

5th June 1969

‘Up at 0930, all the lads up to see us off. The weather wasn’t too good, temperature -16˚C. We left base at 1130 in a blaze of glory with sledge pennants flying and Rod blowing his trumpet in farewell.

Quite sad leaving base, Barrie Whitaker was obviously feeling blue at seeing us and the dogs go. Rod and I were both moved by his gesture at departure.

The weather deteriorated as we got higher up the Piedmont, Count making matters worse by trying to drag us all back to the comfort of base, but he settled down after the first five miles or so. I had only one punch up between (initially) Kelly and Otter, this due to Sexy Myrna coming on heat. Eventually we had to camp due to the wind getting up. We covered 12.3 miles in 4 hours.’

We made progress slowly, travelling when the weather permitted, and as daylight was a rare commodity so early in the spring, and winter storms still persisted, we had to be philosophical. Personally, I struggled with impatience, especially during the days of enforced lie-up.

From my diary:

‘Wind increased even more during the night and continued steady all day, gusting up to 100 mph with no visibility due to the drift. I went out to feed the dogs and got blown over. Not a sound from the hounds, all 18 of them buried in the snow. Just the odd black nose peeping through a sea of drift. For the first time, not one dog howled or even stirred while I groped around in the half light, seeking the spans. Normally, as soon as there is movement in the tent, they start leaping and yelping, a wild and boisterous cacophony of noise greeting you as you emerge through the tent tunnel. Not so today, I had to prod half of them to let them know I’d dumped a slab of “Nutty” (“Nutrican” – field dog food) right under their noses. What weather.

The noise in the tent is terrific, the wild flapping of the canvas, the poles groaning, even flexing visibly under the onslaught of the wind. Outside, great slabs of ice have formed on the windward side. The walls seem solid. We talk and smoke, and occasionally a fierce gust makes us apprehensive, forcing us to consider what we would do if the tent did go. Not a pleasant thought. The air within pants with the pounding of the walls, smoke from my pipe drifts upwards towards the swaying dog harnesses drying in the apex, it shoots from side to side with a speed that catches the eye. Its 2300 now and still howling, though we think the worst is over as we do get a short lull from time to time. It’s going to be a hell of a digging job when we move.’

So, our progress up the island was slow and due to a lot of soft snow, the miles were hard won.

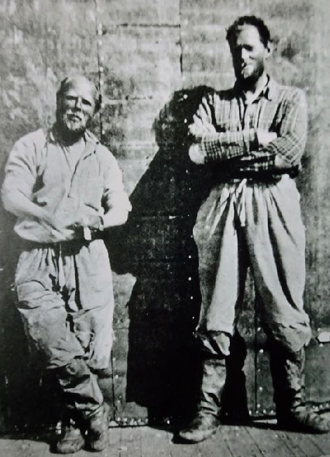

Prior to our departure, arrangements were made with the Stonington & Horseshoe Island based FIDS, that they would come over to meet us. As the main sledging base with more than ten teams, they had far superior local knowledge and certainly more valid experience than Rod and I had managed to acquire during our bumbling attempts to become “proper” dog men, so we were both thankful and pleased that within a few days we would perhaps be able to learn from experts the sledging practices which we knew we lacked.

Notwithstanding our dearth of expertise – which certainly contributed to our slow progress, I was later to learn that some of the conditions we regularly battled with on the Adelaide Piedemonte, were far from normal. For example:-

‘The two hours “travel” were a complete bastard. If anything, the surfaces were worse. Every few yards the sledge got bogged down in the cotton wool we have to plough through. We only covered 2.3 miles at the end of which we had had enough. Real bloody, heartbreaking graft. The dogs worked like hell, really putting their hearts into it, but to little avail. They wallow up to their necks in powder snow, little Myrna almost vanishes in the deep parts. They all “swim” well!

Count behaved tremendously considering the lousy conditions encountered. It’s the hardest work either of us has done for a long time. Even though we stopped to make camp at 1500, it was 1700 before we got in. Just walking from the sledge to the tent makes you almost cry with exasperation. The weight of a box in your arms pushes you down to your thighs in the snow. It takes an age just to wallow a few yards.’

It took us some eleven days to battle our way the thirty miles to the Shambles Glacier and on July 16th, we teamed up with the Stonington men.

To say we were grateful to meet up with a party consisting of seven experienced sledgers and four more dog teams is an understatement, and after the greetings were over, our “convoy” of six dog teams – some fifty-four dogs, set off down the motorway they had created on their way to join us. Our dogs went wild, pulling like mad. What a difference not to have to break trail, to charge along in the tracks of others was like a dream.

From the bottom of the Shambles Glacier, we headed over the McCallum Pass and thence down towards Rothera Point. We camped in the dark after a momentous day. To sledge like this after the experience of the last ten says is like waking up in heaven.

For the next couple of days we remained at Rothera Point in order to move a depot to a more convenient place.

On the 18th of July we sledged across Laubeuf Fjord over good sea-ice passing Pinero Island, a long rocky ridge running north to south in the middle of our day’s run. The view of the western side of the island took one’s breath away, with rock and ice towering above the frozen sea. We camped properly on the sea-ice – a first for Rod and I. My most significant memory of this experience was the desperate struggle we had getting the dog span pickets into the ice, it was as hard as concrete.

That night we cancelled our regular radio schedules with Adelaide Island, as we were now officially Stonington FIDS.

With good weather we encountered lower temperatures, with many days to come below -25˚C. The upshot of this was the vast improvement to the sea-ice surface, which made every day’s travel seem easier than the last. Our route took us over to Blaiklock Island, a sheltered spot with sound sea-ice and a small refuge hut on its western side, containing a good stock of food and resupply stuffs for sledging parties. We took four boxes of Nutty to enhance our supplies. We were tempted to spend the night in the hut, but it was so Baltic within, that we pitched our camp out on the sea-ice and were much warmer for it.

The next day turned out to be memorable both for the fine day’s sledging we enjoyed, but also for its historical significance.

From my diary:-

‘Very cold today -30˚C. We left Blaiklock at 1045 and travelled up Bigourdan Fjord to the western end of the Jones ice shelf which joins Blaiklock to the Heim Glacier on the mainland’s Arrowsmith Peninsula. Beautiful scenery on the eastern side of Blaiklock, the towering pinnacles of rock and ice enhanced by soft white light from the emerging sun which painted the summits pink. A low band of cloud that had drifted down the great valley, carved out by the Heim Glacier made everything seem very still and eerie.’

Access to the Jones is at the northern end of Blaiklock, where a large mass of ice stands proud of the shelf. To the left of this massive obstacle is an ice ramp which was easy to sledge up. The surfaces remained very good, but the cold was bitter, particularly for Rod whose dogs were going so well that he had to ride the sledge a lot. We encountered many areas of crevasses and Rod overturned his sledge crossing one bridge. I dashed back to help him, and in my ignorance, did a stupid thing, by walking back without skis. Sykes, went spare and rightly so. I deserved the bollocking for behaving so bloody daft in such a desperate place. Almost to prove the point, about a hundred yards further on, I went through one, and only the sledge loop on my waistline stopped me from going down. Not a nice feeling. At the eastern end of the Jones, we made camp, where we met up with the Stonington Survey Party, Sheldon, Fielding and Mick Pawley.

We all assembled in their tent for a brew (nine of us!) where, over the radio, we learnt that the Americans had just landed on the moon! What next? FIDS on the moon? Lunar sledging? A great day but very cold travelling.

Food for thought this. There we were, sitting in a tent designed by the contemporaries of Captain Scott at the turn of the century, travelling using wooden sledges, tied together with hempen cord and leather thongs, designed by Fridtjof Nansen in the 1880’s, and cooking on a primus stove designed even before that, while Armstrong and his companions were where they were, due to the very latest of technology. We were all of us in hostile environments and yet both groups coping well with the difficulties presented by our surroundings. I felt then, as I feel now, that we got the best deal.

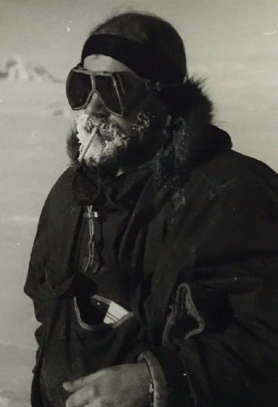

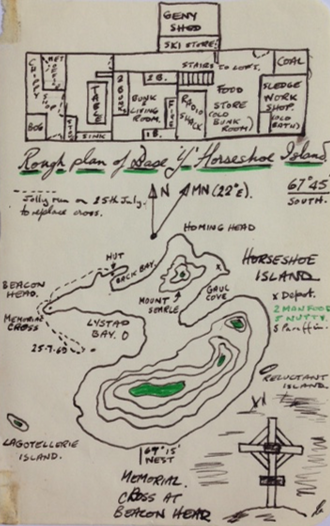

For the next couple of days, we made our way south in indifferent weather down Bourgeois Fjord. We travelled on a compass bearing as visibility was so poor. We spent a night amidst groaning sea-ice, off the entrance to Dog-leg Fjord, and after a further long day of nine hours sledging, we arrived at Horseshoe Island, where Sykes had wintered over. We spanned our dogs out in Back Bay, as there wasn’t enough room on the permanent dog spans for our additional hounds, but Rod and I had the comfort of a bunk inside for a change.

A day or two of “make do and mend” was necessary, in order to get ready for the next phase of our work, but it was great being at Horseshoe Island base, as the setting was magnificent.

From my diary:-

‘The sun shone on Horseshoe Island for the first time since the onset of winter, a beautiful pale light. Mount Searle looked austere and strange, standing out crystal clear in the low sunlight, with the moon still hanging on her shoulder.

There are just six of us here, plus dozens of dogs. Plenty to do. Went down to my sledge and turned it over to clean the runners. What a job, it took half an hour to scrape off the frozen dog shit. It’s amazing how it adheres with such tenacity to the silky smooth surface of the “Tufnol” laminate with which the runners are shod. I also fitted my recently acquired sea-ice picket, which should make setting up camp much easier.The new things we’ve learnt since coming over on this trip have made sledging even more interesting. Suddenly every aspect has taken on a sort of seriousness as one realises that being out for months without any chance of outside assistance, one’s gear is of paramount importance. I could kick myself now when I think of all the necessary bits of kit I could have made up and brought with me had I not been so bloody ignorant. It occurs to me how useful a really comprehensive ‘Manual on Dog Sledging’ would be to anyone coming on to base for the first time. Particularly in circumstances such as Rod and I found ourselves when we arrived at Base ‘T’. (See Appendix ‘Sledging Notes’).

During the winter, Sykes and his team had removed the memorial cross from Beacon Head, which commemorated the deaths of the three FIDS who died on their trip to the Dions, so we made an excursion by the sea ice to reinstate it. Sykes and Flavel-Smith hauled the cross up a gully to carry out the job, while Rod and I ran the ‘Huns’ round Lystad Bay, as it was too cold simply to hang about waiting.

The next two weeks were spent undertaking a sledge-based magnetometer programme in Square Bay, to the east of Horseshoe Island. Rod and I were accompanied by two geologists, Ian Flavel-Smith and Mike Burns. We had to carry a very delicate magnetometer so, in the hope of avoiding wrecking it, we arranged a system of suspending it within a framework on the sledge with ‘Bungee cords’. Not very traditional or aesthetically pleasing, but Heath Robinson would have been proud of our design. Our new task only involved light work and as the scenery was quite spectacular, it almost seemed as though we were on holiday. Over the period, we established two camps on a semi-permanent basis and went out with light sledges to measure the magnetometer lines, this entailed travelling in set patterns over the sea ice taking readings at intervals of three-tenths of a mile.

The nature of the work was such that we only needed two teams each day, so our dogs got a day off every three days, though judging by the row they made when the two ‘teams de jour’ left them behind, I suspect they thought they were being punished.

From my diary:-

‘Beautiful day but cold -30˚C, calm and clear, but spoilt for me by my own fault. It was the ‘Huns’ turn to remain in camp, so I went with Flavel and the ‘Admirals’. My boob was forgetting my sheepskin sledging gloves and my Helly Hansen hood. I brought them out of the tent with me but left them at the entrance, and we’d gone some way when I discovered them missing. Flavel offered to go back for them but I said I’d be okay. For the next six hours I had to make every effort to keep my finger ends from going. What a bastard! I never managed to get them warm all day. The discomfort was made worse by the fact that my hands stiffened up and were almost useless. What little warmth I generated between survey stops was almost instantly removed. I muddled through, but I’m afraid I wasn’t much use to Flavel. The surfaces were good and we managed to link up the centre line between Camp Point and Horseshoe. All in all my coldest day yet, much more uncomfortable than actually sledging proper at -40˚C.’

We returned to Horseshoe Island on 10th August, as the various parties working in the area were intending to head back to Stonington for the main summer work together. Meeting up at the base naturally resulted in a bit of a boozy party. Many sore heads in the morning! The ‘brew’ consisted of gin and lime and plenty of Drambuie which had been brought over from Stonington in two large oil tins, presumably to ensure the precious stuff wasn’t lost through breaking the bottles. Despite the somewhat greasy taste, the whole lot vanished and all told, we managed a reasonable glow.

Just prior to leaving Horseshoe for good, Mick Pawley and I climbed Mount Searle, an impressive but lowly peak at 1761 feet. Although it was still -30˚C, the ascent brought on a bit of a lather, causing icicles in beards and hair frozen in one’s hood.

We went up by the West Ridge, which was a good scramble. Once on the crest, one or two steep bits made me think twice about going further without a rope, but the intrepid Mick carved his way across the top of two meeting gullies and cut steps up a steep snow bank back onto the rock. I went upwards gingerly to say the least.

On reaching the top we had a fantastic view, being able to see the sheer bulk of Ridge Island to the north and right over Square Bay to the mountains of the peninsula, with Mount Wilcox dominating the scene, with its towering triangular summit. We came down by the steep gully, which I didn’t feel too safe on, due to the rocks being plastered with ice and snow. Once over these difficulties Mick initiated me into the finer points of ‘arseading’ which seems an excellent way of getting down a hill.

It took us four days to reach Stonington as we had to lie up at Camp Point due to high winds, prior to making a final sea ice camp at Cape Calmet.

From my diary:-

14th August

‘Felt very cold when we finally lobbed out of the tent. The mountain mass of Adelaide stood, monolithic, hovering over a sea of swirling mist. The sky was so clear that one felt one could see beyond infinity – almost like looking into one’s soul. I felt very moved to be here in such incredible conditions. Swung the psychrometer and it registered -41˚C, over -70˚F. I don’t think I was alone in feeling some elation as we set off for Stonington. I led with some 300 lbs, Rod followed with 600 lbs, and Flavel brought up the rear with a bit more. It felt really cold, but once moving our kit kept us warm enough. An unfortunate aspect of such extremes of temperature, was the sand-like consistency of the snow. It was impossible to slide alongside the sledge on skis, and we had to walk the nine miles to Stoners.’

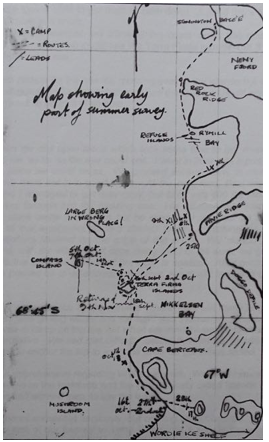

The next three weeks were spent at Stonington, mostly making preparations for the summer field work programme. Final plans regarding what work was to be done, and by whom, took some time to emerge but eventually myself and the mighty Huns were assigned to undertake the topographical survey work in the area of the Wordie Ice Shelf, some 60 or 70 miles south of Stonington.

Our team would be made up of two parties, each comprising a surveyor, and two GA’s with dog teams, tasked with getting the surveyors and their equipment to the various places where they wished to establish survey stations. Each team worked independently of the other, usually some ten or twenty miles apart, and by measuring distances and angles between survey stations, to construct an accurate geometric grid between these known points, as a basis for making improved maps using a series of aerial photographs which had been taken by an earlier American aircraft based survey. Brian Sheldon and Jack Donaldson were the GA’s who would assist Mike Fielding, and Mick Pawley and myself would help Paul Bentley

In those days before the advent of G.P.S and computers, survey equipment was both heavy and very cumbersome. So in addition to our normal camping gear and large food supplies, we now had to transport some 200 lbs of survey equipment and a petrol generator, with fuel, in order to keep some of this kit charged and operational. This weight of instrumentation, most of which had to be carried to each survey station was the main reason why two full dog teams were required to support one surveyor.

To reach any survey station necessitated each man carrying a 60 lb load. Load 1 was a bloody car battery! Load 2 was a hulking brute of a machine called a tellurometer which was used to measure distance electronically and load 3 a theodolite, tripod and an Aldis lamp, which enabled angles to be measured with sufficient accuracy. Being appointed as a GA to the Survey Team was NOT considered to be the best job for a GA!

Anyway, before we could embark on this extended journey, we had much preparation work to do, and the days being base bound afforded ample time to check over my sledge and make the modifications I deemed necessary. I also had a bit of a problem with one of the dogs in my team, as Otter, my gentle giant developed an enormous swelling in his mouth which with reference to a veterinary book, led us to believe it was a Ranula. The recommended treatment was to give the dog a general anaesthetic and ‘liberally cut out the swelling’.

We mixed up some pentathol and gave him 10 mls intravenously, via his fore leg. I’m not convinced he got it all, as we had to have a go at both legs. He was a tough old bugger. Eventually, he collapsed and with me holding his mouth open, Shaun cut in, just below his tongue. Whoosh! About 2 pints of mucus like fluid gushed out. He came round almost straightaway and refused to let us see what we had done, so we put him outside to recover. Within minutes he was tearing into a great lump of half-rotten seal meat. What a dog! We weighed him shortly afterwards as an indicator if he should deteriorate. He weighed in at 107 lbs, almost 8 stones. As I said, what a dog. After some discussion I decided to drop him from the team as a recurrence of the Ranula when out in the field would clearly create difficulties.

We all tried to keep our dogs exercised, mostly just on local runs due to the general need to prepare for the summer trips. I managed one decent 50 mile outing over three days, out to an abandoned Argentinean ‘Refugio’ on Millerand Island, offshore in Marguerite Bay. By the beginning of September we were ready for the off.

We had an auspicious start to our journey, as we made great progress round Neny Island and round the promontory of Red Rock Ridge, reaching the depot at the Refuge Islands just after noon, where we collected a further ten days of food. This put my load up to 660 lbs and Mick, who was following up to over 900 lbs. The surface was good and the extra weight made little difference to our progress. The weather eventually closed in, forcing us to travel on a compass bearing, but eventually we reached the other side of Rymill Bay, to close the land again at the northern end of the Bertrand Ice Piedmont. We were separated from the fast ice along the land, by a large tide crack and as we were crossing it a seal popped up causing chaos amongst the dogs. A seal to a husky is as irresistible as a running cat to your average dog, and it took a while to get them to calm down. A good day’s run though as we covered 25 miles in 8 hours.

The following day, in indifferent weather, we followed the coast round and made camp near Moraine Cove, from where we could see the Terra Firma Islands, our first survey point, some 15 miles out to sea.

The weather was far from perfect for the sea ice crossing over to the islands but as we were camped in a spot notorious for Katabatic winds, we decided we should have a go. The day was to turn out to be a bit of an epic.

From my diary:-

‘We hadn’t gone far when we met open leads which took some time to get round. Great ridges of pressure ice, as far as the eye could see. I went in front with a probe and eventually found a place we could cross. We crossed several more, in close order and we realised we were not in a good place. At the next lead, Paul went ahead with the probe and I managed to get over okay, but Mick with 400 lbs more weight on his sledge went through into the freezing sea. His situation was made worse as he had a ski stuck under the sledge but he eventually got clear as the sledge, with 1000 lbs of our equipment aboard started to sink. Fortunately, it stopped when the handlebars jammed on the edge of the crack. We started to unload, with difficulty and, with the magnificent dogs doing most of the work, we got the sledge out and onto the ice floes. Much of our gear is soaked. After getting ourselves organised we pushed on in deteriorating weather, eventually travelling on a compass bearing.

Our situation was getting more serious by the minute. There were still many large cracks in the ice, visibility was getting worse and the wind was increasing. The last thing we wanted to do was to camp on the ice, but when the wind increased to about 30 knots we had no alternative. We had real difficulty getting the tent up, requiring the use of a climbing rope to anchor the top to a sledge while we got things sorted.’

We were all nervous and apprehensive regarding where we were. We were camped in half a gale, halfway between the mainland and the paradoxically called Islands of Terra Firma. We went to bed worried men, to say the least.

We spent the following hours somewhat nervously, but nothing nasty occurred. We survived the night. The rest of our journey to Terra Firma was a joy, as the wind stopped and the sun came out, allowing us to cover the remaining seven or eight miles on good surfaces. We encountered no more fear-inducing cracks or leads in the sea ice until we closed the land, when we noticed a large break running from the end of the northern most island towards Alamode Island. We made camp close in, on the landward side of the tide crack. It all felt very secure, when contrasted to our last resting place. It was a good day’s sledging. Tranquillity and equanimity had been restored. A few days later we experienced a retrospective backlash to our difficult day out on the broken ice.

From my diary:-

‘One of the most traumatic experiences I have ever encountered occurred last night, or should I say early this morning. We were all well asleep in the pitch black of the tent, when suddenly all hell broke loose. Paul was screaming and shouting for help! I woke up with a hell of a fright. Couldn’t see a thing, just the noise of Paul thrashing about in the dark. I could also hear water splashing and a hand out of the sleeping bag went into ice cold water. I was convinced that a lead had opened up underneath us. A mad and utterly fearful couple of minutes followed, while we tried to get some light on. I felt over to where Paul was and he wasn’t in his bag. All the time I could hear him shouting “Help, help get me out.”

Eventually Mick found the torch. Snap! And there’s Paul, shaking with fright on top of the food boxes. We tried to calm him down and checked the tent, and what was happening outside. All was okay. It came out that he had had a nightmare, woken up in terror, and tried to get out of the tent, and in doing so, had upset the large pan of water we had melted for the morning’s tea and porridge. He said he dreamt he had been in an avalanche. The most horrifying awakening I’ve ever had. It took me hours to get back to sleep. What caused it I wonder?’ In retrospect I would think the fearful events when we dropped a sledge into the sea might have had something to do with it.

Despite our difficulties, we were now in a position to start our survey work. Sledge ‘Alpha’, the other survey team, were camped some 35 miles north of us at the Refuge Islands, and our first task was to complete the measurements for this line and also a line from Compass Island, some 10 miles northwest of our current position. Aware that we were quite a long way out on the sea ice, from the relative security of the mainland coast, we were quite anxious to complete this work as quickly as possible, as we already had experience of how rapidly ice conditions could change. However, due to various problems arising, we were destined to spend the next two weeks on or around these isolated islands, mostly due to the vagaries of the weather, either generally, or specifically at each end of the line we were trying to survey. Measuring the angles was the main difficulty, as this required being able to see the Aldis light at the other location. We made some progress, albeit slowly and on 14th September, the weather seemed sufficiently settled to attempt a trip out to Compass Island and measure this, our most problematic line. To take advantage of what might be a small weather window, we decided to leave our main camp and supplies standing and make the trip carrying only the survey gear and emergency survival kit.

From my diary:-

‘Left camp at 1030 and on good surfaces, covered the 9 miles out to Compass in 2 hours. En-route we had something of a fracas when we passed half a dozen seals. The hounds went mad with excitement doubtless dreaming of a good feed. They totally ignored our commands and we had to resort to the ‘Thumper’ to get them under control. They are, to a dog, a wilful bunch of buggers when the mood takes them.

When we climbed up to the high point with all the gear, we discovered we couldn’t do the line at all, as a large tabular berg was ‘parked’ right in the line of sight, making it impossible to take theodolite bearings. Not much we could do but come back. “The best laid plans of mice and men…”

The weather deteriorated and by the time we got back it was snowing and blowing like hell. At one stage I thought we were in for another epic, but things eased a bit and we got back okay.’

We spent many futile days trudging up to the station we had set up on the highest point, without being able to get the angles measured. It was very frustrating for all concerned which meant that when some incident occurred that broke the depressing pattern, it was most welcome.

From my diary:-

‘A wild cacophony of doggie noise caused us to leap out last night. A great fat seal was wriggling towards the dog spans. A couple of .45 bullets from the Webley pistol stopped the row and assured us of a few days of fresh dog food, plus liver and steaks for ourselves.

Mick and I went out with the ‘Tilley’ lamp to gut it in case the stomach contents tainted the meat overnight. When we opened it up we found a perfectly formed foetus in the womb. Felt a bit queer gutting it especially when hooking the three foot long infant out. I think it moved. Christ! It’s an alien existence, killing one’s own food.’

A few days later, Mick spotted another one way out on the ice so we went out with the ‘Huns’ and knocked it off. The dogs behaved pretty well. As the entire business is extremely messy, we put a hole through its lower jaw and dragged it back using my trail rope. It wasn’t a big seal but we did get 18 feeds off it, plus a couple of feeds for ourselves.

Although we had plenty of ‘Nutty’ to feed the dogs on, an extended trip like this, every opportunity to give the dogs fresh meat has to be taken and, given that our plans had to be modified later, these windfalls were very important to the success of our journey.

Towards the end of the month we were ready to move further south and, in order to replenish our food and fuel stocks, we made a trip over to Moraine Cove. Leaving the bulk of our supplies at Terra Firma. We made an easy trip over and back, returning with another month’s fuel, man food and Nutty.

The remote nature of our next survey area required that we establish a food and fuel depot at the northern end of the Wordie Ice Shelf. This took us four days as we were forced to lie up for two days close to the ice cliffs at Cape Berteaux.

From my diary:-

‘Drift snow plummets from the gaunt and foreboding crags behind the camp. An evil wind, blustery, bold, boisterous and a bastard. The lulls are the worst; after a period of wild flapping and banging of the tent, everything goes deadly quiet. One’s ears prick up at the strangeness of it. Faraway one hears a whirling whistle then bang! The tent sides cave in as though someone was applying a high pressure hose on it. The poles creak and the ‘house’ starts to shake and flap wildly. The gear hanging in the apex starts to dance and the trembling of the tent can be felt through the lilos.

Occasionally, a far off rumble can be heard as an unseen chunk of the ice-cliff breaks away from the land and starts its slow journey to destruction. The whole campsite is alive with moving ice. Some large cracks have appeared near the cliff with huge chunks of pressure ice thrust through. It’s only a few yards from the tent, but I don’t seem to worry about it, which is a bit weird for a coward.’

We returned to Terra Firma and, with persistence we eventually managed to measure the Compass Island line and by the 11th October we had completed most of our northern work. Something of a struggle which had taken us over a month.

For the ‘Huns’ though, a major development had occurred. By moving Myrna, my young bitch upfront to run with Count, she very quickly picked up the role of ‘leader’. As the days progressed, she got better and better so by the time we departed for the serious sledging on the Wordie Ice Shelf, the ‘Huns’ acquired a new and very competent lead dog.

Over the next few days we moved camp down to the depot we had established on the Wordie, where we now had 25 days’ supply of food for all and if Alpha brought the 10 days they promised to bring, we could remain out in the field for 35 days, prior to returning to Stonington, via Terra Firma, where further supplies were available. We had a plan! All we had to do now was complete it. Our first station was on Deschanel Peak, which we reached on 18th October, measuring a line to the Puffball Islands, where Alpha was based, during the next couple of days.

Eventually, both our parties met up at our camp. We sledged down onto the ice shelf to guide Alpha through a badly crevassed area, which was changing constantly. Many of the holes were large enough to swallow a whole team so luck and good judgment were necessary in equal measure.

(Photo: Ian Curphey)

It was good to have a bit of company, other than our own, but as time was precious we soon had to go our separate ways, though we did travel together for a couple of days, some of which was quite challenging.

From my diary:-

27th October

‘Left Deschanel and started on the glacier section of our trip. Fantastic scenery unfolded as we gained height. I led with the mighty ‘Huns’, taking a line traversing the south side of Baudin Peaks. This provided an easy ascent. After a few miles we could see the beautiful ‘Alpamayo’ – like ridges that flank Doggo Defile, with the tortured ice of the Clarke Glacier below. Sledged down into the upper basin. Really immense crevasses and rifts on our left, but found a safe route through, clear of the chaos.

28th October

We sledged in company with Alpha as far as Elton Hill where, after taking some additional supplies from them, we adjusted our loads and set off with 1,500 lbs between us. The route was interesting and the scenery bloody marvellous. Hag Pike, which we passed en-route for Confluence Cone is really impressive – a straight sided tower, rising 1,000 feet above the ice. We encountered a lot of hard sastrugi, which didn’t do much good to heavily loaded sledges.

We had one nasty incident, which could perhaps have been avoided. Mick took a line through an ice fall, when we dropped down from the Col between Brigg’s Peak and Mount Gunter, the result being that Hamad and Nasr found themselves hanging by their harnesses ten feet down an evil-looking crevasse. The blue bottomless type. We made everything secure and I held the team stationary while Mick managed to drag them out, none the worse for wear. Close to losing Nasr though, as he’d almost slipped out of his harness. We camped a few miles south of Mount Gunter.’

29th October

between the right hand ridge and small buttress

(Photo: Ian Curphey)

‘Sledged the last leg to Triune Peaks. I led with 620 lbs and Mick with 900 lbs. We dropped down onto the back of the Wordie proper. According to the map, the great slope we had to descend shouldn’t have been there. I couldn’t see the bottom of it, so I put a keel down and traversed slowly to the east. Eventually, we reached the bottom, where the surfaces deteriorated into soft snow. We arrived at Triune Peaks at 1315 hours and pitched camp.’

This was significant for us as this was where we would establish our last survey station, prior to returning north to Stonington. It was a fitting place to finish on, as the peaks before us were dramatic, spectacular and very beautiful.

We started off to establish our last station straightaway as the weather was set fair. There were clearly technical difficulties to be overcome owing to the steep and even sheer nature of the mountains. It was obvious that we would not be able to set up station on the summit but a lesser peak on the south ridge would suffice, though access to the saddle that separated it from the main summit looked far from easy. The good weather held, and over the next two days allowed us to organise the station and start the line.

From my diary:-

‘Due to the crevasses at the start of the way up to the peak, we man hauled the survey gear as far as we could manage, replacing our dogs by ourselves. We backpacked the rest of the way and roped up.

Mick came into his own here, fixing a traverse rope across the narrow steep snow ledge at the top of the lower cliffs. Once he’d secured everything, getting the gear up was safe, but hard work with 60 lb loads.

Paul set up his theodolite in glorious sunshine. We were perched on a narrow ridge underneath the fantastic central peak of Triune. Such a majestic yet foreboding mountain. Spires and sharp flutes of snow rent apart by sheer rock bastions. We had hoped to measure the line to Deschanel, but it wasn’t possible due to Alpha reporting high winds.’

October 31st

(Photo: Ian Curphey)

(Photo: Ian Curphey)

‘A successful day, we managed to get the tellurometer measurements by noon and returned to camp. We left all the equipment in situ, except for the battery, which we had to bring down for recharging.’

Our good luck ended here, and we spent the next six days tent bound mostly because of poor weather down at Cape Berteaux. Time was running out for us now, and although we did manage another tellurometer reading, it was too bad at Alpha’s end to measure the angles. In fine weather, I harnessed my dogs up and made a recce trip out onto the Wordie as we were intending to leave the next day.

From my diary:-

‘Sledged out onto the tracks I put in yesterday. The first 8 or 9 miles were no problem, but eventually we had to cross a large rift full of ice falls. A bit desperate at times with many large open crevasses with doubtful ‘bridges’ and great areas of cracks that we had to sledge across. Fortunately, we managed to get back onto the land with a bit of a struggle, taking a welcome break at Deschanel Peak. We decided to continue down to the sea ice, while the weather was okay. This involved making our way to the ramp we used before. We encountered some really evil holes which we were forced to cross on ropey bridges. One particularly nasty place was about 25 feet wide and smashed through about 30 feet from where we crossed. Dry mouth for a while. At last, back on the sea ice again. If one goes through here you only fall a couple of feet into the water! A good run of some 26 miles.’

The next day we returned to our old camp at Terra Firma, hopeful that we might be able to tie up the few loose ends of the survey work remaining. We were just in time for six more days of lie-up due to lousy but warm weather and wind. I suspect it was this long lie-up that turned me into a murderer! I killed using a short ice axe. Tiny black eyes peering up at me, a little figure in a white waistcoat, not more than a foot high. Bop! And the deed was done, the little motionless body lying in the snow makes me acutely aware I’m not the same man as I was. All I could think of was how he’d taste fried in lots of butter with dried onions.

(Photo: Ian Curphey)

The warm weather brought with it new problems. The surface of the ice was starting to melt and eventually the floor of our tent was soaked. As there was little point in moving the camp, we resorted to bringing Nutty boxes inside to create a false floor.

This worked, but severely restricted the amount of room we had in the tent. Unpleasant times. But worse was to come before things got better.

On 16th November, there was a break in the weather and we managed to complete the very last line and measure the angles. Finished at last! However, from the survey station we could see a vast stretch of open water near Alamode Island and many open leads to the west. We all agreed it was time to make tracks north.

The next day we received even more startling news from Stonington, who reported that the ice has gone out completely from Red Rock Ridge, so it is impossible to go back to base via the sea ice.

Penguin, a rare sighting (Photo: Ian Curphey)

We had some serious and difficult discussions as to what we should do. Mick was all for making a dash for the mainland, finding a route up a glacier to the plateau and then sledging back over land, getting back to Stonington via the Northeast Glacier. As this route wasn’t proven, I was dead against it and even though Paul was prepared to go along with Mick, I refused point blank, even stating that if necessary I would take my chances on my own and try to sledge south to King George VI Sound and thence to Fossil Bluff. It was all very fraught, but the ‘cowardly’ caution which I had adopted as a shibboleth had firmly wedged itself in my mind. However, we all agreed on one thing, whatever we decided to do, we would have to dump all the survey gear and pick up as much fuel and dog/man food as we could in order to affect our escape by a much longer route. With this in mind, Mick and I sledged over to Moraine Cove, dumped the wretched survey gear, and picked up a load of goodies.

On 18th November, the weather was clear so we climbed Twig Rock to do an ice recce. To the north there was open water everywhere and the route back over land was now clearly out of the frame. Only one course of action was really open to us – to head south over the sea ice before the retreating ice caught up with us. The ice front was now only ten miles north.

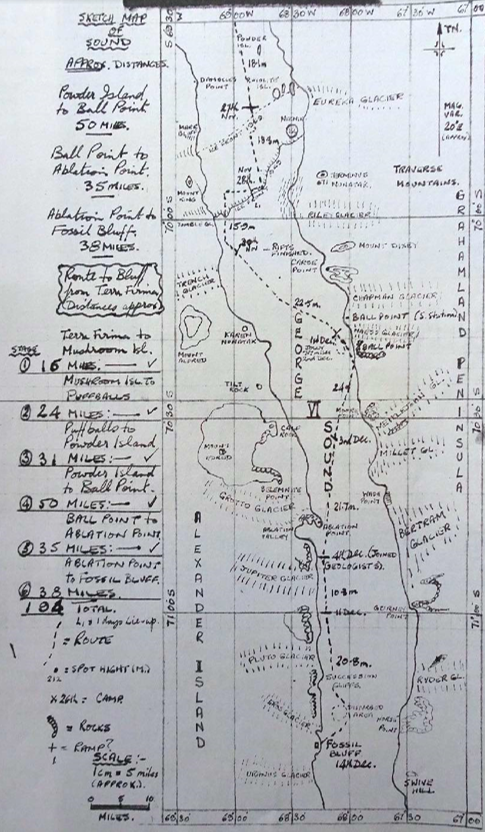

With the arrival of sledge Alpha, another round of futile discussions opened up. For myself, I tried to keep out of it, as the debate was essentially being carried on between the survey men. I busied myself copying sledge Alpha’s map of King George VI Sound as I had no maps that extended south of Powder Island.

The journey south to the safety of the Sound took us eleven days, including two days lie up due to the poor weather. Prior to our setting out, some rescheduling of the work programme being carried out at Fossil Bluff meant that I was on my way to a new job! Acting as GA for Mike Bell, geologist, who was working on the outcrops of Alexander Island. The prospect of this cheered me up no end, as Mike and I had gotten on well on the way down and briefly on base.

Our route south was established, having been used by countless FIDS over the years – Mushroom Islands, Puffball Islands, Cape Jeremy, Powder Island, South Ice Front, 1949 Ice Front, Ball Point, More Point, Ablation Point and Fossil Bluff.

One other sensible thing was agreed, that due to the warm temperatures during the day, with the sun being high, we would change over to ‘night’ travel. There was more or less 24 hour daylight now anyway and the surfaces would be better.

Some diary extracts:-

‘We had to run out on a compass bearing as the Puffballs are quite small and the sea ice down here is littered with icebergs, making identification of a low snow covered island difficult. The bergs were strewn across our path, some of them over a mile long and trying to find our way through them was difficult. We encountered a large six foot wide lead, and probing revealed no safe place to cross. Eventually, we got across by sledging over the shoulder of a berg where snow had accumulated, that was adequate to hold our weight.’

‘Mile after mile of flat ice, not many bergs either. We have passed to the south of the Wordie and there is just flat sea ice as far as the eye can see. No trouble with leads and there is a general feeling that we’ve cracked the potentially dangerous bits. Not dead sure myself, I’ll feel better when we get round Cape Jeremy, Really enjoying this trip now, as we are getting the lion’s share of leading. The ‘Huns’ can do anything! ‘

‘Sledged to the edge of the Barrier (1949 Ice Front), via a tide crack and a short ramp. Difficult undulating surface slowed down progress. Sadly we came across a wide crack full of choss. We plodded along it for over a mile and a half, but no chance of getting over. Made camp and Mick and I went out again to find a route, with success after a hard hour. One minor incident. My dogs turned at a crucial moment pushing Ziggie down a crack into the sea. While I was pulling her out a fight broke out. Raced upfront to get stuck in and the bastards dragged Kelly and Ziggie back into the hole. Shouted for Mick to give me a hand and we managed to eventually get a track in over to the other side. We went back to camp after being on the go for 12 hours, pretty done in.’

(Photo: Ian Curphey)

Thursday 4th December

‘The last day of the mighty sledge ‘Alpha’ and ‘Charlie’ combine. I led mainly to save time, bringing some weight over to my sledge from Brian’s unit. The surfaces were really good and, after travelling for four hours we were almost level with Ablation Point, having covered 15 miles.

In the distance we could see a tiny black dot which turned out to be Mike Bell on skis, coming out to meet us. The usual round of FID handshakes, then on our way to the geologists camp. We pitched close by and during the morning changed over the personnel into the new units. Mick Pawley, Henry and Paul (surveyors) are bound for the Bluff. Brian Sheldon is joining Mike Elliott and I am teaming up with Mike Bell as planned.’

Sledge ‘Charlie’ dies the death with no fierce shows of emotion. I think all concerned are fed up with each other’s company. Not desperately, but enough for all to appreciate the possibility of doing something different after a long survey season. New faces make everything seem a bit unreal, one tends to forget that other people exist!

The next week or so I accompanied Mike on his geological trips, moving camp between the South Ablation Valley and Spartan Cwm. My main role was to find routes through the enormous pressure ridges that were piled up along the full length of Alexander Island, caused by the ice of George VI Sound being constantly pushed by the dozens of glaciers that fed into the Sound from the mainland, some ten miles away to the west.

Working on the side of a rock mountain was strange, when contrasted to the essentially ice bound world that had been my lot for the last several months. Once we had made our way through the pressure ice, which was a daily occurrence, as there was no way we could have got the ‘Huns’ through and established a land based camp, one entered terrain akin to the spoil heaps of a Welsh mining valley. To do our work we scrambled up rocks, ran down screes, and even forded streams, albeit of melt water. The hills we climbed in quest of samples were in the region of 2,000 feet high above the Sound ice, so we had ample opportunity to stretch our legs.

(Photo: Ian Curphey)

Halfway through December, with Mike’s projected work completed we packed up and travelled the last few miles of the Southern Journey to Fossil Bluff. For me, a dream completed – a journey by dog sledge of over 1,000 miles.

It was particularly strange being amongst so many people again, sixteen of us congregating there on 14th December, all busy making plans to either sledge back over land or beg a flight back to Adelaide Island, when the planes started to fly. This was my necessary choice, as during my year down here, I had decided that in fairness to Mary back at home, I would reduce my contract to one year. So therefore, I had to return to base with the ‘Huns’ in time for the arrival of the relief ship. This would ensure that I could carry out a proper handover to the GA who would be relieving me. I wanted fervently to do a much better job in this regard than Bugs McKeith had done for me and Rod.

From my diary:-

19th December

‘Awoke this morning to the news that a plane was coming in to take me back to Adelaide Island. In scenes of chaos, I packed up, the dogs howling, slush everywhere and a bright sun high in the sky.

Eventually my wonderful lunatics pulled me and my gear up to the landing strip. As we arrived, so did the plane, passing over head some 30 feet above us. The dogs were terrified.

Packing all the equipment in the plane created problems, but after some squeezing everything in and getting the dogs anchored down a bit, we finally took off and headed north over the mountains. The dogs behaved remarkably well, mostly due to fear I suspect, but it may have been out of reverence of the ‘Big Red Bird’.

The flight back was as awe inspiring as it was strange. Spectacular views of the many miles over which we had sledged but a very marked contrast in time. It had taken us several months to wend our way from Adelaide Island to Fossil Bluff and now we were racing back there in two hours. This fact only added to my belief that fieldwork using our wonderful dogs was not going to survive much longer.

After all, no dog sledger could possibly make a good argument for how effective dog teams were in carrying out remote survey work. Wonderful yes. But effective – hardly!’

Being back on base felt extremely strange as the relief ship had been in and many new faces and the incredible hustle and bustle had a real alienating effect. I felt like a fish out of water and even Christmas was a very low key affair for me. I was more comfortable talking to my dogs on the span than hanging around the base. However, I did have plenty to do as I had to complete Journey Reports for our travels and also make out a comprehensive dog report, along with a store’s inventory for equipment for the following year. All this took time.

The last day of my sledging year involved preparing for my last field trip, when I would hand over the ‘Huns’ to Richie Hesbrook, the incoming GA and Adelaide Island’s new base leader.

From my diary:-

‘Finished off my ‘Dog Training Report’ and then got the gear ready for the coming field trip. One incident caused a bit of a problem. I brought Kelly down to the hut for a treat but on the way back up to the spans he got caught up with Tuva. Really vicious fight. Tuva had Kelly’s leg and it took a few swipes with a wooden mallet (the only thing I had to hand) to make him let go. Then Kelly got a grip on Tuva, by the snout, the result being a big stitching job on both dogs. Kelly’s wound is too bad for him to run with the ‘Huns’ tomorrow.

Big Richie is coming with me, and Bill Taylor wants to accompany us all with the ‘Rabble’. It’s a pity about having to leave Kelly behind but it’s his own bloody fault for fighting!

From my diary:-

1st January 1970

‘Bill, Richie and I left base at 11 pm last year and saw the New Year in ploughing up the Piedemont with the woofs. A beautiful night, if one can call it that, a fiery orange sun splattering its rays across the mountains and filling our sledge tracks with liquid shadows.

Once we had gained some height, perhaps about 1,000 feet, the surfaces improved and we fairly clipped along with our small teams. We only had 14 dogs between us. We spread them out to make them look a lot!

We passed all the old familiar landmarks, the crags below the Window, Trig 6, Hooley Corner etc. Feels good to be back. Struck me as ironical as we sailed along, that Rod and I spent 10 days hard travelling to cover the distance that we did tonight in 8 hours.

A really good day’s travel, to cover 25 miles and climb 3,000 feet, quite a feat for our dogs. When we stopped they all flopped down like rag dolls, absolutely knackered. Travelling with Richie Hesbrook tends to dwarf the ‘Huns’ and our equipment – he’s 6′ 4″.’

For the next couple of days we had to lie-up due to the weather, but this wasn’t wasted, as there was plenty of time to fill Richie in on many details regarding the dogs and travelling in general. It’s always good experience to have to lie-up in bad weather. One needs the training!

However, we did get another successful day’s travel in, covering a further 22 miles, reaching Bond Nunatak, well up the island. Another 7 days tent bound followed, bringing home the fact that sledging isn’t all beer and skittles. This happened to be the longest period of lie-up I had to endure during my time sledging. We ran the 50 miles back to base in a couple of days, with the end of my dog driving days being 13th January 1970.

From my diary:-

‘Beautiful weather again. Struck camp at 2300 hours and set off back to base. What a night, beautiful soft colours everywhere, the sun constantly changing shape due to miraging. At one time it was like a haystack, shimmering gold and swaying in a pastel sky. Soft blues and mauves filled the southern horizon, and to the north a giant earth shadow cast fingers of dark onto the burning mountains.

As we sledged along the snow came alive with sparkling crystals, a myriad eyes reflecting and scattering the light from the low sun. The surface was the best I have ever sledged on, with only six dogs, at one stage we were doing about seven miles an hour. Swish! The hard crust of the ice crystal surface speeds us on our way. We ran close to the mountains, but kept well clear of crevasses. What a night. What a beautiful night.’

This was a good note on which to end my time with the ‘Huns’. They had transported me some 1,200 miles over the 10 months we had been together, but now, sadly it was over.

I was to remain on base for four weeks before embarking on the ‘John Biscoe’ for the first leg of my voyage back to the UK. Base life continued much as it had when I had arrived here almost a year ago. There was much to-ing and fro-ing, as the relief ship moved personnel about and resupplied the sledging bases. With my report writing completed, I busied myself overhauling my field sledge to ensure that Richie inherited the second most important piece of his field equipment next to the Huns, in top class order. I had hoped to do this while he was available, but his task as incoming base leader meant that there were other more pressing demands on his time. Changeover on base was always a bit frantic, as so many necessary things were in constant competition for priority attention.

In consultation with the Doggie Man at Stonington, my pleas of dog poverty resulted in Adelaide getting seven more dogs which would be of real help to our teams during the coming season.

During my time sledging – notwithstanding the horrors of contracting Giant Urticaria before the winter set in – my health had remained good and I’d magically avoided any injury. It was therefore somewhat ironic that in my last week on base I managed to break my foot as a result of kicking a recalcitrant Count soundly up the arse. My pain following this act of stupidity was made worse by the fact that I’m certain he smirked at me before going back to his place at the front of the team. Although I had officially handed the Huns over to Richie, I still used them round base to do dog feeds and the like.

Adding insult to this injury, I was quite badly bitten by a new dog – again due to my own stupidity. We had received several new young huskies from Greenland to improve our breeding stocks following the ‘Mass Vasectomy Programme’ mentioned earlier. We kept one at Adelaide and the others were bound for Stonington.

From my diary:-

‘Whilst sorting out the dogs to go to Base ‘E’, ‘Kovic’, one of the Greenland dogs sunk his teeth into my left forearm. I was more amazed than anything else but it was entirely my fault. I had ignored the telltale signs that he was scared stiff and in my haste to get him on the plane, I’d roughly grabbed hold of him by the collar. He squirmed his way round somehow and properly ‘dented’ my skin. A short and deep hole, showing several bits of the interior mechanism of my arm was my deserved reward. Cleared it out with acraflavin and started a course of tetracycline.’

On St Valentine’s Day, I finally bade farewell to Adelaide, Base ‘T’. My dogs were in good hands with Richie, a compassionate and good natured man. And the Huns liked him. It felt very strange shaking hands with those I had overwintered with. I certainly had second thoughts regarding my decision to shorten my contract.

I spent the next month on the ‘John Biscoe’ engaged in the usual duties of FIDS, helping to load and unload at various bases. Many returning FIDS took advantage of the fact that the ship would call in at Punta Arenas, at the very southern end of South America and disembarking there, would make their own way home via the USA using public transport.

While I did not wish to undertake such an extensive trip, five of us managed to arrange to get off in Punta Arenas and then get picked up in Montevideo, Uruguay, a month later. Thus providing an opportunity to see something of Chile and Argentina and yet still return to the UK at the normal time.

And so after getting a ‘sub’ in US dollars on our wages, Sykes, Flavel-Smith, Whitaker, Wager and myself ‘jumped ship’ on the 21st March and, after a confusing start, headed north by bus to Puerto Natales, which was close to the famous Torres del Paine. The next day or two was spent exploring this beautiful area; as regular tourists.

Ian “Curf” Curphey, GA, Adelaide, 1969