“We set off about 11pm on New Year’s Eve – singing Auld Lang Syn to encourage the dogs up the Piedmont…travelling at night to get the best running surfaces and by the light of the midnight sun… The three of us were sharing one camping unit under the call-sign Sledge Victor… It was a superb night and we covered the 25 miles to Lincoln in exactly 8 hours. Incidentally I am now driving a new, super-charged, twin-carb’ Rabble, reinforced by three new dogs.”

To avoid the crevasses we knew to be opening up towards the mountains, we took a slightly different route to the one used on previous journeys. By heading towards Window Nunatak for just 3.5 miles before running on a bearing of 340M, we found there were no major depressions and only a single, well-bridged crevasse to cross.

My Letter:

When we got up at 1800 the next evening (1st January), we ran the Huns over to the crag, but even though we probed, we failed to find either the depot we had put in before mid-winter, or the rocks that we had placed it on, and it is now written off. It probably lies under the winter’s snow accumulation and what looks to have been an avalanche.

We set off from Lincoln at 2200, running on a bearing of 015M towards Bond, but the weather rapidly deteriorated. The wind rose to an estimated 25 knots and the cloud descended to Piedmont level, forcing us to camp after only 4 miles, so beginning a lie-up that was to last for 36 hours.

About 3 o’clock in the afternoon of 4th January, the sun was blazing through a thin mist. We were dozing on top of our sheepskins in a sweltering tent, waiting for the sun to sink towards the horizon (night) when the surfaces would freeze up. We were woken from our stupor by the dogs howling and barking, and then heard the engine of the Turbo-Beaver. Scrambling out of the tent, we saw the plane buzz the camp and throw down a cigarette tin containing a message to call them up on the radio frequency the message provided. We tuned in and Bert (the pilot) requested that we mark out a landing strip threshold. He needed to land to pick up one of my dogs, which was now needed by the Picts, presently on the Grahamland Plateau. We responded by stomping out an arrow in the snow and liberally scattering cocoa in the arrow-head to produce a clear runway marker. Bert made a safe landing, his two passengers took photographs, and after a swift cuppa, they took off with Shrimpie on board to recce the crevassing on the Shambles before returning to base.

Later that evening, at 1830 and with reduced teams, we set off in mediocre weather, crossed the 10-mile wide head of the Shambles Glacier, and sledged on northwards at a fast pace on good surfaces for a total of 22 miles, covered in just over 6 hours. We didn’t see a single crevasse. This brought us to Bond Nunatak, and we camped about half a mile out from the crag where we hoped to find the depot.

No sooner had we stopped than it started to blow (we estimated 20 knots) and snow, and that was just over 6 days ago, so we are now in our 7th day of lie-up. We did have a lull for a couple of hours around 1300 yesterday (8th January), and being a bit too near the end of our food for comfort, ran the dogs to the foot of the Nunatak to look for the depot, finding it without a problem. We took 1 box of man-food, 2 Nutrican dog-food and 5 gallons of paraffin. We then dug out the camp in the hope that we would be able to move on, but no luck, for soon it was snowing and blowing again – to the extent that the 6000+ foot mountain less than half a mile to our east could not be seen.

I completed the story of this field trip in a letter written on 22nd January.

When the weather cleared up on 12th, we decided that we could not afford the food to travel to the north coast of Adelaide.

Curf’s Journey Report:

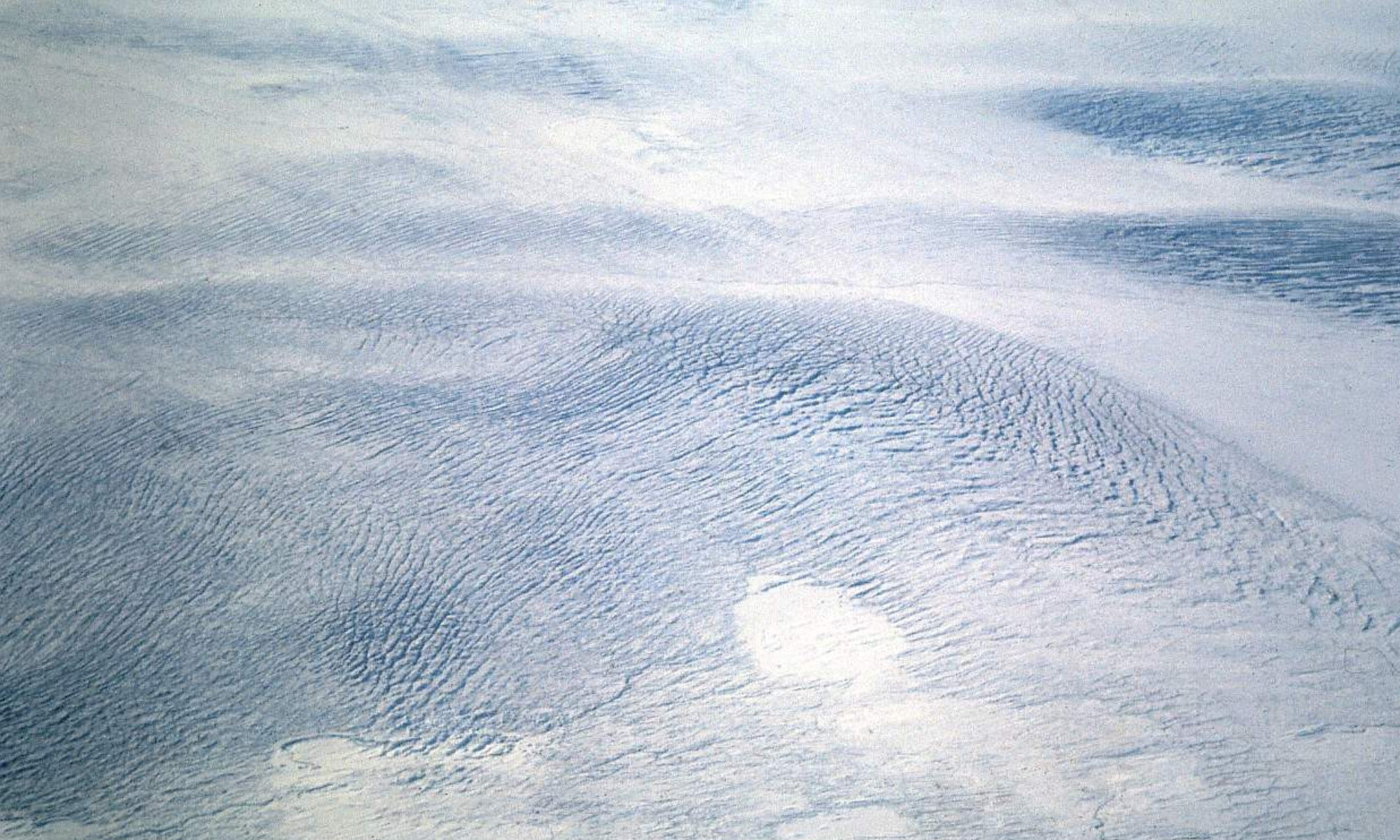

“At last, a real break in the weather. Up at 1800 and dug ourselves out to the surface in bright sunshine. We left Bond at 2030 and sledged south. Surfaces were not too good at first, but improved as we got out of the influence of the Nunatak. The setting of the sun towards the horizon also crisped up the surface. We took a line a bit further west than on the northward run, heading for a point about 3 miles out from Lincoln and camped at 0500, having covered 22.6 miles in about 8 hours. Temperature was -10C.”

My last run with the Rabble was across midnight and into the early hours of 13th January.

Having broken camp, we set off at 2300 on 12th.

Curf’s Report:

“From Pinnacle, we ran closer in towards the mountains than on the trip up the island, and as a result, saw the crevassed areas previously reported. We had no problem finding a route through, but in bad light it would be far better to stay well out from the crags. We arrived back at base at 0500, having covered 26.1 miles in 6 hours. It had been a very enjoyable day. The temperature was -10C.”

I knew I would never get another run like it. So it was that my Antarctic dog-sledding career came to a memorable finale. It was a performance that has fed me with positive memories for a lifetime.

When Curf wrote up the Journey Report quoted above, he began with a quotation from Herman Melville’s “Moby Dick”. It captures both one of the lasting memories of the journey and Curf’s special brand of humour.

“We had lain thus in bed, chatting and napping at short intervals, when, at last, by reason of our confabulations, what little nappishness remained in us altogether departed, and we felt like getting up again, though day break was some way down the future. Yes, we became very wakeful, so much so that our recumbent position began to grow wearisome… ”