Header Picture – VP-FAP at Fossil Bluff – Rob-Campbell Lent

Twin Otter VP-FAP Engine Change – at Fossil Bluff (continued)

My first awareness of the Marguerite Bay “By Fids for Fids” website was in January 2020, when I received an email from Dave Rowley (Twin-Otter Pilot, Adelaide 1969-1974) suggesting I might like to take a look at it. I had a look, enjoyed what I saw and read, but my two summer seasons there were so long ago now, and my job at the time seemed so technical and mundane in comparison to what the “Real Fids” were doing, that I could not imagine that any contribution from me would be of any interest.

However, a few months later in April I had another email from Dave saying he was about to write an account of the 1972 engine change we did on the Twin Otter VP-FAP at Fossil Bluff, and suggested it would be interesting to read an airmech’s view of the event.

So, I read the introductory “About” notes on the website encouraging contributions, and then the extract from Mike Warr’s Book ‘South of Sixty” where he explains “How It All Began for one Fid”. Mike’s account of his 1963 interview with Bill Sloman, and subsequent events sounded very similar to my own interview and induction into BAS by Bill in 1970. I had a copy of Charles Swithinbank’s “Forty Years on Ice”, and read his chapter 10 “Our Propeller Stops (with a clunk)”, to get some long-forgotten details on the story.

But it was the Stonington “Ching Stick Party” story by Ian Sykes in his book “In the Shadow of Ben Nevis” that made me finally decide to write this story.

Continuing From Adelaide Page:

I started doing some research into my own small collection of documents: 35mm slide grips; my original little green book for Fids the 1970 BAS handbook from my Introductory week of Antarctic lectures at Cambridge; and a diary that I still have of my first summer at Adelaide Island Base T. I spent an amusing few minutes yesterday afternoon reading some of my diary entries from 50 years ago, and realised there were so many words there that were part of our everyday vocabulary at the time, that I have never heard or used since then.

My wife Jane gave me a strange look when I laughed and read some of them to her, particularly Scradge, Gash, Smokoe and Ching Sticks. Having tried to explain to her what a Ching Stick was, and not having much success, I googled “Antarctic Ching Sticks”, and to my amazement, up came Ian Sykes book with the Stonington chapter describing a Ching Stick Party following a long-awaited mail delivery. Having been in exactly the same position myself, longing for hand written letters with news from loved ones at home, but dreading the crushing news of a letter starting off with “Dear John, I’ve met the most wonderful man, we were married last August etc.”, I found his description very accurate. But fortunately for me, I experienced the former emotion, without the latter!

It was the Ching Stick story that made me think that perhaps I could write a story that wasn’t just about aircraft nuts and bolts, and the trials and tribulations of fixing faults in aircraft engines or flight control systems without the luxury of special tools or equipment. The Adelaide version of the Ching Stick event that I remember involved the unlucky Fid doing a slow and solitary dance in the Bar, banging the end of the (broom) stick on the floor with his every step to the beat of some loud, but probably inappropriate music. I had not realised until reading Ian’s Stonington story that each one of the several metal beer-bottle tops cumulatively nailed to the broomstick and producing the distinctive Chings with every stomp, represented the receipt of yet another “Dear John” letter.

The Fossil Bluff engine-change saga on Twin Otter VP-FAP began on 11th February 1972 after completing about 7 hrs of intensive and very low-level flying doing aerial radio echo sounding (ice depth measurements). After refuelling the aircraft, Dave Rowley was starting the Port (Left side) engine in order to taxi to the tie down points, and although the turbine was winding up, the propeller didn’t move, so he shut down the engine. The two aircraft engineers, Dave Brown and I, were back at Adelaide, so Bert Conchie flew DB down to Fossil Bluff in the Beaver to inspect the engine and try to determine the cause and what could be done to get it fixed and the aircraft flying again.

The propeller would first have to be removed and then the reduction gearbox unbolted from the front of the engine to look inside and trace the fault. Using materials that fortunately were available at the Fossil Bluff hut, the pilots and engineer Dave Brown constructed a timber and canvas shelter over the wing and engine to protect the exposed innards of the engine from wind and weather, while DB removed and inspected the suspect parts. The inspection resulted in some metal debris being found inside the gearbox, and the De Havilland (DHC) aircraft Customer Technical Support engineers in Canada were told what Dave had found. The instructions from DHC were that the engine could not be repaired in the field, and would have to be changed before the aircraft could fly again.

There was one obvious small problem though, and one bigger one. The small problem was there was no spare engine! The bigger problem for the aircrew and engineers though, was in two parts:

1. It was unheard of in the past to carry out major repairs like a complete engine change in the field, hence the many wrecks of previous BAS aircraft scattered around the peninsula, and I think perhaps consequently BAS was sceptical about getting DHC to ship another engine South; and

2. Other than from the two pilots Dave and Bert, who fortunately did have faith in our abilities, I detected a strong consensus of opinion from many of those involved, that Dave Brown and I did not have the skills, equipment, tools, facilities, time, etc, etc to actually change the engine at Fossil Bluff. It was suggested that the best thing to do might be to dig a ramp and deep depression in the snow, drive the aircraft into it, and cover it with snow for the winter. Then arrange for a team of ‘Proper Engineers!’ with all the special tools and lifting equipment to return next summer, dig it out of the snow and replace the engine. Maybe the ‘powers that be’ were even preparing to write the aircraft off being so close to the end of the 1971/72 flying season?

Due to the impressive performance and operational reliability of the Twin Otter and Turbo-Beaver in previous years, no-one had witnessed Dave Brown or I doing more than routine maintenance and some minor system trouble-shooting on either of the two aircraft. I knew Dave Brown had spent many years as an aircraft maintenance engineer in various parts of the world, so I knew he was more than competent to do the engine change on FAP, and I was completely confident we could both do the job together. All we needed was the new engine!

It was probably my previous job prior to joining BAS that made me think like that, and maybe Bill Sloman picked up on this when he interviewed me in London. For the two years or so immediately before then, I was working in Malaysia doing heavy airframe and engine maintenance work on helicopters with either piston or turbine engines, and “Steam” Beavers with Pratt & Whitney 9-cylinder radial engines. This involved stripping down the aircraft completely, inspecting the parts, putting them back on the aircraft and doing the test flights etc. I guess I was removing gas-turbine or piston engines and refitting them in various aircraft as often as about one every month or six weeks, sometimes more often. For about my last six months in Malaysia based in a small town called Kluang in Johore State before going to BAS, I worked with a small mobile team, travelling all over the country in a Bedford 3-ton flat-bed truck with a HIAB hydraulic crane on the back, and a Land Rover with our tools and equipment in the back. We would go out to replace engines or gearboxes, or recover unserviceable Beavers or “dead” Westland Scout and Bell 47 helicopters. We used the HIAB hydraulic crane on the back of the truck to lift u/s engines and gearboxes out of the helicopters, and lower new ones back in again, and also to load dead helicopters onto the back of the truck and drive them back home.

(Photo: Rob Campbell-Lent)

In the previous Summer season at Adelaide, the only unusual job I had to do was get VP-FAM (the Turbo-Beaver c/n 1640) tail-ski repaired so it could continue supporting the teams in the field. On 18 January 1971, FAM had landed on a hard and resilient Sastrugi area in the field, and the tail-ski had buckled and cracked, making it unserviceable and grounding the aircraft. A new tail-ski was ordered from DHC in Canada, and the long process of shipping it to Adelaide had started. But in the meantime, I thought it was worth trying to repair it and get the aircraft flying again.

There was nothing to lose, as a spare was on its way, and would get here eventually, but everything to gain if it was quickly repaired. There was no stock of aircraft quality aluminium sheet of the correct thickness available at Adelaide, but I had noticed a suitable-looking engine cowling panel on the side of the wrecked Single Engine Otter on the Adelaide ski-way, the remains of VP-FAL #377 DHC-3 Single Otter.

See the full story of VP-FAL here

So I removed it and used it to fabricate and rivet a sheet-metal top-hat section reinforcing patch to the damaged area of the ski. We fitted and tested it, and continued flight operations with it until eventually the new ski arrived in Adelaide. If there is anyone reading this with memories of a close relationship with the wrecked Otter on the ski-way, then I hope you will feel ok about my recycling of the engine panel for a good cause.

This was the only thing of note I can recall about my first season at Adelaide, other than joining the Antarctic swimming club by falling into the icy water off the jetty when trying to step ashore from a boat bringing us home from an entertaining evening onboard the Endurance! Dave Rowley will also recall that on another occasion, possibly in the 1972 Summer season, when the entire complement of Base T manpower was assembled on the jetty, hot and tired after having just completed the unloading of next year’s aviation fuel in 45-gallon drums from the ship’s scow to the jetty, and moved them all up the hill to the aircraft ski-way on a Maudheim sledge towed by the stripped-down “utilurker” (the modified Bedford tractor). We both decided to jump off the edge of the jetty and into the sea amongst the lumps of brash ice bobbing around.

(Photo: Rob Campbell-Lent)

Sadly, there was not much reaction from the Fids when they saw an easily replaceable spanner-bending mechanic in the water. But the absolute stillness followed by the dawning horror that was visible on everyone’s faces, when they saw their aircraft pilot floundering in the icy cold water and beginning to seize-up while trying to swim back to the jetty, was like a scene from a dramatic suspense movie!

(Photo: Rob Campbell-Lent)

But to continue with the saga: Dave had flown the Beaver FAM back to Adelaide with the Echo-sounding crew, Charles Swithinbank and Mike Walford, leaving Bert and Dave Brown with the help and support of the Fossil Bluff crew (My apologies if I am wrong, but after 48 years my memory is not that clear! I think they were George Kistruck, Malky Macrae, Martin Pearson and Ian Rose) to finish constructing the tent over the Twin Otter wing and engine, so we could replace the engine when it arrived. They also installed a Herman-Nelson heater and hoses to heat the inside of the shelter so we could work long hours in comfort while changing the engine. I had been at Adelaide all the time, and was unaware of the difficulty Dave Rowley had had in convincing BAS HQ to get a spare engine shipped to Adelaide on an AOG basis, and I was always convinced that the spare engine would be sent down to Adelaide.

From my low pay-grade perspective, the only problems would be the logistics of getting it from Toronto to Fossil Bluff so we could do the job. Ignorance is bliss! Dave Rowley had no doubt whatsoever that we would return VP-FAP to Downsview, the DHC factory in Toronto where the aircraft spent every Summer. Fortunately for all of us, Dave’s insistence and powers of persuasion with BAS on flying a new engine South finally paid off. DHC air freighted a new engine to Punta Arenas, where the Bransfield picked it up and transferred it to the John Biscoe in the South Shetlands to bring it to Adelaide. The complex logistics effort required and achieved in getting the new engine from Toronto to Fossil Bluff were quite amazing, and was only possible because everyone involved worked so hard.

The new engine arrived on the John Biscoe at Adelaide on 24 February. It was safely enclosed in its special steel shipping container, which was extremely heavy and much too big to lift or fit in the Beaver cabin for the last part of its journey to Fossil Bluff. We brought the engine ashore and removed it from its steel box where it had been secured in a special storage mounting stand. This would have been ideal for helping us swap the necessary parts from the old engine to the new one before hoisting it back up into the nacelle wing mounts on the aircraft. However, we had to leave it behind and lift the engine by hand, into the back of the Beaver, laying it carefully on inflatable Lilo beds, and securing it for the flight to FB the next day, 25 February.

(Photo: Dave Rowley)

A spare engine does not normally get shipped from the factory with all the external parts fitted to it for the systems which it needs to function, so it cannot simply be lifted out of its shipping box as a complete power plant, raised up into the engine nacelle, connected up and started. This applied to our new engine. The engine fuel and propeller blade pitch controls; the electric starter motor; electric generator; exhaust pipes; stainless steel fire-wall sections; hydraulic and vacuum pumps; and all the flexible hoses carrying fuel and oil to the engine had to be moved across from the old to the new engine. In addition to this, the complex wiring loom, or “Harness ” of electric wires and connecting plugs which carry such things as ignition to the starting system; power to the sensors that measure and send signals back to the cockpit instruments showing propeller speed; turbine speed; exhaust gas temperature; engine oil temp and pressure etc; had to be transferred from the old to new engine.

After all the components had been re-fitted, the pilot’s engine control rods, levers and mechanical cables had to be connected and check-rigged for correct function and range of movement, with any adjustments made as required. Most Fids flying as passengers in the Twin Otter will have seen the pilot’s Right arm raised up in the air and his hand holding on to the levers and handles in the centre of the cockpit roof, and twisting the handle grips or moving them forwards or backwards as the aircraft takes-off or lands. All these movements have to produce the correct adjustment on the corresponding engine or propeller, and both sets of levers have to produce exactly the same results and response to each engine or propeller, so when the levers are aligned in the same positions as each other, the engines and propellers can be synchronised with each other in flight, and the cockpit indicators show the same readings. This rigging check and adjustment process can sometimes be quite complex and time consuming.

Every one of these components is attached with several very small items of hardware such as nuts, washers, bolts, screws, clips and clamps etc, and often secured in place with split-pins, vibration-proof lock-washers or locked together in groups with lengths of twisted stainless-steel locking wire. The components are often located in places with limited access and sometimes no visibility, and the small nuts, washers or bolts etc. that secure them to the engine can be easily dropped to the ground while the engineer is working blind using the tips of his fingers trying to locate and fit them.

Due to the heat in the shelter from the Herman-Nelson heater, the snow on the ground beneath the area we were working was melting, creating small pools of water and wet slushy snow, mixed inevitably with small amounts of spilled aviation fuel and engine oil, plus any debris that had accumulated under the wing during construction of the tent and removal of the propeller and engine, so if we dropped any small but vital item into that slush, we would probably never find it. All experienced aircraft engineers will have a set of “pickup and retrieval” tools in their basic toolbox, and we both had our own. (I still have mine now at 72-years of age, and sadly seem to be using them on an increasingly regular basis doing simple domestic jobs around our home!). For ferrous-metal objects we had a small but very strong magnet on a long telescopic handle, and for non-ferrous items we had a long flexible “mechanical fingers” tool with a tee-handle and release button. We had some spare items of attachment hardware available, and our pick-up tools were always near at hand, but we were very much aware of the dire consequences of dropping and losing any simple but irreplaceable part that would slow-down our progress while we searched for it, or if we could not find it, stop the engine from operating safely or, in a worst-case scenario, stop the aircraft flying!

We started the work of swapping various parts from the old to the new engine the same day it arrived at FB, gradually re-assembling all the bits required to make the new engine complete enough to be installed. We used an amazingly simple but efficient pair of Haltrac domestic-use garage manual mini-hoists made of small pulleys and long lengths of nylon parachute cord to lift the engine (approximately 130kg) back up and install it, and then re-install the propeller. The Haltracs were suspended from the wooden beams that also held the canvas sheet over the shelter. The biggest problem we had to overcome was while lifting the new engine up and into the nacelle, it is critical to align the engine and airframe attachment mounting holes and corresponding bolts correctly, without damaging the close-tolerance surfaces and bolt threads in the process, not to mention the airframe structure itself. Unfortunately for us, the heat of the Herman Nelson space heater had melted the snow under the left wheel-ski, and the aircraft was tilted with one wing tip considerably higher in the air than the other! In a more normal situation, on a hard-concrete floor, with the lifting crane chain and hook hanging vertically at right-angles to the horizontal wing, it would be a simpler job to raise the engine to the correct height, and slip in the bolts with just finger-tip pressure. But for us it wasn’t a vertical lift anymore, and it was a struggle to line-up the attaching bolts and holes in the engine mount frames. We had to take some of the weight with our shoulders and try to push and hold the swinging engine so the bolts just slid into position. You can’t risk hammering the attachment bolts into their holes with brute force, and then worry about any Stress cracks and bolt or vibration-mount structural failures developing as we were flying North over the Drake Passage or Brazilian jungles on our way back to Canada! Relief all round when it was done though, as it meant we could all fly home at the end of the season!

It took us a week to install the new engine and prepare it for the first ground run and flight test on 2nd March. Both Dave Brown and I flew on the flight test piloted by Dave Rowley. Experience has shown that it is always reassuring to any pilot that the engineers who have done the work are confident enough about the integrity and safety of their work, that they fly with the pilot on any such post-maintenance flight test!

After the final engine control adjustments were completed the next day 3rd March, we all flew back to Adelaide in it, taking great pride in the successful results of our aircrew team, and Dave made a celebratory low-level fly-past of the Bransfield as it was arriving at the same time as us.

The Air Unit completed the season’s work and both aircraft VP-FAP and VP-FAM departed Adelaide on 20 March 1972 and arrived at the De Havilland Canada (DHC) factory at Downsview, Toronto, Canada on 28 March 1972.

Rob Campbell-Lent. BAS Air Unit Aircraft Engineer. Adelaide 1970-1972.

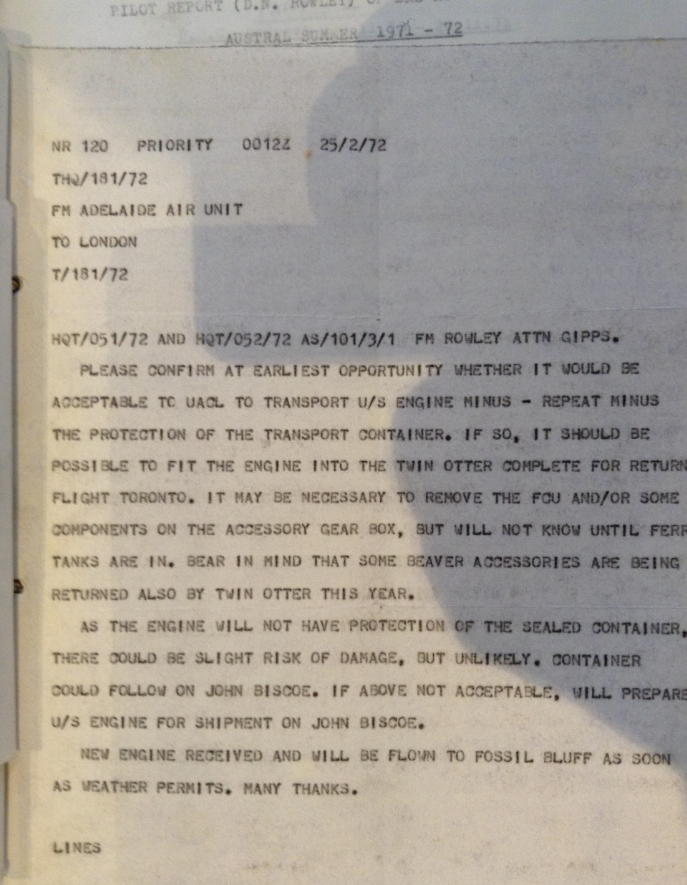

Documentation