Airborne Adventures Across West Antarctica (continued)

1982-83 South Shetland Islands – ‘El Scientifico’ ties up some loose ends

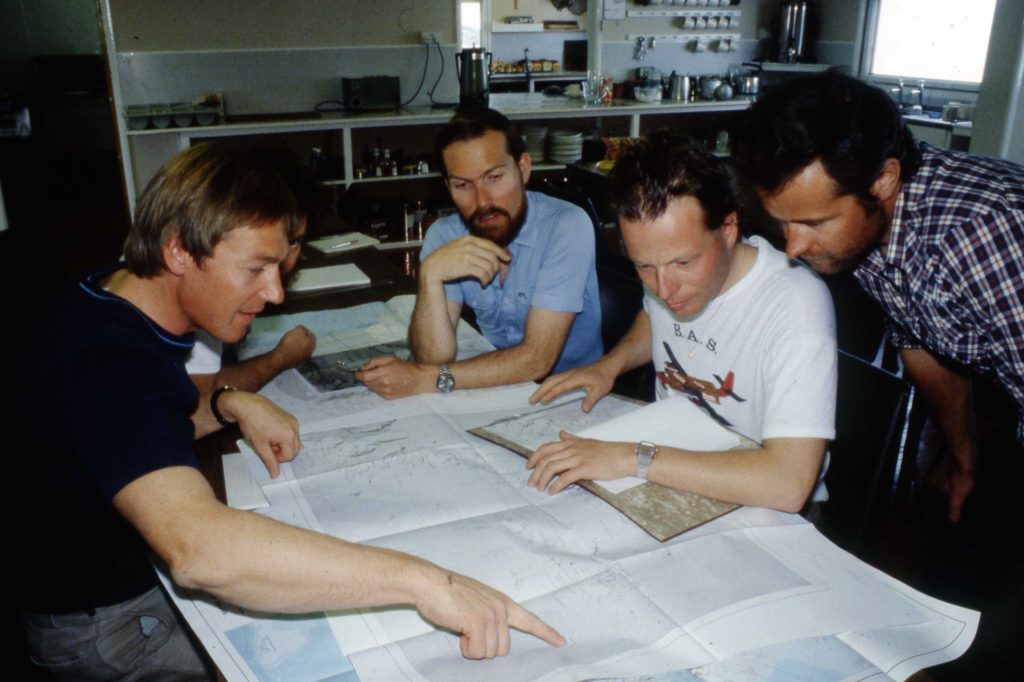

(Photo From The Camera of Steve Garrett)

We flew north from Rothera in mid-December 1982 to stay with the Chileans at Teniente Rudolfo Marsh, returning after Christmas The project had dual objectives – to take photos of penguin colonies for John Croxall in the South Shetland Islands and on the edge of northernmost Graham Land, and to acquire some aeromagnetic data over Bransfield Strait and long ‘tie lines’ parallel to the Antarctic Peninsula to link existing profiles. These tie-lines joined the ‘loose ends’ of profiles flown across the peninsula, allowing us to finish consolidating the data from decades of gravity and magnetic surveys, concluding the work started in the 1960s by Professor Don Griffiths and realised in the field by many FIDs under the leadership of Geoff Renner.

The flying was memorable. Silver light of cloud rolling down the mountains on the east coast of Adelaide Island. Stacked lenticular altocumulus. Knife-edge cliffs of James Ross Island. Peaks and glaciers of Trinity Peninsula. Green sea in the crater of Deception Island. Glimpses of the penguin colonies through the hatch at the back of the aircraft.

Although grey, cloudy and rainy, King George Island is interesting as it was (and still is) crowded with bases from many nations. We visited the Russians at Bellingshausen in December when partying was somewhat inhibited by watchful eye of the KGB commissar. There was a considerably more free-spirited party with the Brazilians in January. The main consequence of our stay with the Chileans was my new name. The rooms at Marsh were given name tags, and mine had a new spelling and job title that stuck for all my subsequent fieldwork – to the extent that new pilots marked my name as ‘Garretti’ on aircraft manifests the following season.

1983 Ronne Ice Shelf – the mank, diversity and scones

We finally got to the Ronne Ice Shelf in late January 1983. We followed the ice front and due to low cloud had to stop off at a Russian summer base. They fed us well and offered us saunas (which we declined). The contrast in technology was evident. The Russian radio room glowed in the dark with all of the valves and the Russian aircraft and helicopters belched black smoke and looked like they had been built with girders. We were interviewed by an East German film crew. This required someone more skilled than us to translate fluently between Russian, German and English.

After the hustle and bustle of the ice front, it was good to move ‘inland’ to depot 6 away from the ice front to get some peace and quiet. We got into a routine of a days work and then a day of two of lying up as the cloud (mostly low manky stratus) came back in and held stable by temperature inversions. Our very flat world shrank to three tents, an aircraft and a pile of fuel drums.

I’d spent most of the early flights at the base camp with ‘Taff’ Williams the air mechanic to keep an eye on the base station magnetometer. As the season went on, Taff my tent-mate and oppo also kept a watchful eye on ‘El Scientifico’ as I became by turns lyrical about our situation, a little over-enthusiastic about the science and then absent minded about domestic arrangements. In return I could calm him down during his running battle with the malfunctioning generator. One of the unexpected benefits of living at close quarters with very different people is how this built a respect for the benefits of what we now have learned to call ‘diversity’

Our airborne surveys were intended to complement the Ronne Oversnow Traverses which included flying over their route. At the start of the 1983-84 season we made unscheduled landings to deliver scones to the Ronne Oversnow party and then to Andy Smith at the Doake Ice Rumples – which raised a few eyebrows when Kitty Hall processed the data back in England.

1984 The Ellsworth Mountain – Thiel Mountain ridge and extreme tourism

A large joint project with the USA had been planned to look at the junction between East and West Antarctic, with geological and airborne geophysical parties. As our part in this we were able to camp at Ellsworth Camp (in Sentinel Range) and Martin Hills (at 84OS). Our furthest point south was to refuel at the Thiel Mountains (at 86OS). Daylight was continuous and the weather on the ridge was excellent. However, significant magnetic perturbations accompanying the aurora (that we couldn’t see) were recorded on the base station magnetometer on many ‘nights’ . These effects would have interfered with the geological variations we were trying to measure. So we kept to 9am-5pm office hours for flying. This all provided useful experience for our German scientific visitor Detlef Damaske to apply in his subsequent many seasons on the other side of the continent.

Prior to our departure from Rothera there was an unusual visit to the airstrip. A DC3 tri-turbo ski-equipped aircraft piloted by Giles Kershaw brought a celebrity crew to climb Vinson Massif in the Ellsworth Mountains as part of the Seven Summits project. On one hand, it was good to meet and greet the mountain celebrities. On the other hand, I did feel a little conflicted . If anything went wrong with their expedition we would be duty-bound as the nearest humans with a plane to interrupt our work to offer assistance. This was perhaps a seminal moment in Antarctic ‘extreme’ tourism, paving the way for future commercial ventures in the Ellsworths and beyond across the land we were to survey.

(Photo: Bruce Herrod)

When we were in the field we enjoyed the luxury of American Jamesway tents, fuel flubbers (big rubber bags) and frozen steaks. During our stay at Martin Hills there was an exchange of dogs between Rothera and the New Zealand Scott base on the other side of the continent, with the Hercules pilot starting the return flight with the roll call “We’ve got ten P.O.B. and one D.O.G.”.

Analogue to digital conversion

Some of our equipment was still very analogue, notably the radio echo sounder (ice radar) which recorded an oscilloscope trace on a rolling photographic record which needed to be developed each night in the field. Other equipment was increasingly digital. The airborne aeromagnetic data logger programmed by Jim Turton recorded our position and readings on tape cartridges, and we progressively replaced our land recording devices to more reliable digital devices. Jim even tried me to get to learn hexadecimal machine language – but it did not stick in my mind. When on base we could also use the data logger as a micro-computer with a text processor for writing reports – a real innovation at the time. I busied myself on base at the end of the season writing up field reports, which I proudly presented on return to Cambridge – only to be told by Earth Science management that the dot-matrix printer was not acceptable and secretary (the long-suffering Gill Tew) would have to re-type the whole lot by hand. We then had to hand colour our maps and hand draft our figures for scientific papers, so the full digital conversion was to take a bit longer.

(Photo: Steve Garrett)

Steve Garrett – Geophysicist – Rothera, 1981-1984 (Digital image processing by Chris Bell)