THE COROMANDEL JOURNEY

Tim Christie

Introduction

In spite of the fact that I had accidentally dropped my tellurometer over a five hundred foot cliff at Carse Point and that my fellow surveyor, Paul Gurling, had lost all his survey equipment (worth probably at least E30,000 at today’s prices) when it was blown away by a ferocious katabatic on the Harriet Glacier, by Christmas 1971 we had completed the survey task assigned to us by BAS which was to provide an accurate survey link between Stonington and Fossil Bluff, thus linking Graham Land and Palmer Land.

It involved, amongst many other things, measuring three 50 mile long tellurometer lines across the Wordie Ice Shelf to an accuracy of a few inches and measuring a theodolite angle from Mount Edgell to a cairn which we had built on the summit of Butson Peak, near Stonington, the previous winter, which was 105 miles away!

Although forging the Stonington to Fossil Bluff link meant that our official survey programme for the year was complete and definitive maps of West Palmer Land could now be plotted, we had become increasingly aware that there was another, almost equally important, survey problem that needed to be solved – that was to extend our existing survey framework over the central Palmer Land ice cap and into the un-surveyed mountains of East Palmer Land. In the previous year’s official survey report it said that it would not be possible to do this, because the surface of the ice cap was so high that the mountains of the east could not be seen over the top of it from the survey stations on the west, and that in these latitudes there were no inter-visible rock exposures on which intermediate survey stations could be established.

During the following winter I had begun to question this last statement, as a number of old records (including a distant oblique aerial photo taken from over Alexander Island by Finne Ronne some thirty years before) suggested that there might be a small isolated exposure of rock way out in the middle of the ice-cap which could be visible from both sides of the plateau. We called this hypothetical rock outcrop “Coromandel”***, but as the evidence for its existence was not very convincing, we decided in early December that while we were waiting for the other survey party to return across the Wordie Ice Shelf, we should sledge up to Samarkand, a 6000 feet high nunatak on the very edge of the plateau, from where we were certain we would be able to see Coromandel if it existed.

When we got there however, and looked across the plateau to where we thought Coromandel would be, there was absolutely nothing there. The weather was clear and we could see across to Mount Andrew Jackson nearly one hundred miles away, but of Coromandel, there was not a sign. So, we were confronted with a paradox – three independent pieces of ‘historical” evidence suggesting that Coromandel might exist somewhere out near the middle of the plateau, and the evidence of our own eyes which said that it didn’t exist at all!

But, human nature being what it is, and in defiance of all common sense, shortly after Christmas we said good bye to our fellow surveyors (Sledge Charlie) in the Batterbee mountains and set off across the plateau to look for a chunk of rock which almost certainly wasn’t there!

There were three of us in the party: Drummy Small with the Huns; Miles Moseley with the Gaels; and me with the survey gear! What follows is an account of that journey based on my day-by-day

*** In John Masters novel called ‘Coromandel”, the hero learns of a strange place in the east called Coromandel from an ancient map of dubious validity. We called our hypothetical nunatak “Coromundel” because it seemed to be a strange place in the east whose existence was based on equally dubious evidence.

The Coromandel Journey

On New Year’s Eve we replenished our supplies from the Depot at Castle Rock, turned our backs on the Batterbee Mountains and headed out at last across the plateau in search of the hypothetical Coromandel.

The good weather was coming to an end with the Old ‘Year and we saw 1972 in lying-up in a white-out below the last feature of the western mountains, a small outlying rock on the extreme south east of the Throne complex. When we were able to travel again, we found we had turned the last corner and were able to set course direct for Coromandel. Visibility was still nil, but then on the plateau there was nothing much to see anyway, but we felt distinctly uneasy heading off into the white “bundoo” on a course which all our instincts told us must stretch on and on for over a hundred featureless miles. If Coromandel did not exist – and all our recent evidence pointed to this – then our next landfall’ would be the Eternity Range (if we were lucky). If Coromandel did exist then it was probably a rock barely breaking the surface of the ice which would slip past unseen, for how else could it have remained hidden from such elevated view points as Samarkand and Scotch Corner.

Jan 3rd 1972 Still misty. Travelled on a bearing of 10 degrees magnetic – one gentle rise, then dead flat, straightforward going in white-out. The fascination of the featureless plateau wears off in about ten minutes! One distant view of a white rockless peak (part of the Throne) away to the left. Nasr went lame. Allegedly I had harnessed him wrongly. Camped after only nine miles.

The next day, Jan 4th, it was just the same except that the visibility was rather better and the surfaces, rather worse. The dogs were clearly bored with nothing to see anywhere and progress was tedious. Ahead of us the mists seemed to be thinning, and occasionally they parted enough to reveal a bank of dark cloud sprawled rather ominously across the plateau ten or twenty miles ahead of us. I was as bored as the dogs were so I wasn’t really concentrating very much and it wasn’t until about the third mist clearance that I noticed that the dark cloud hadn’t changed shape at all since we had first seen it. Ever so slowly it dawned on my disbelieving consciousness that this was no cloud but a very substantial mountain rising in our path. Almost at the same moment Miles, who was leading, stopped his dogs and called back:

“What the Hell’s that?”

“I was just wondering myself actually”

‘Surely you must know what it is. It’s a ruddy great 5000 foot mountain”

As the party’s surveyor and map maker I was supposed to know what everything was whether I had been in the area before or not. This, mountain, if mountain it was, appeared to rise in an area marked on all maps (even those of our immediate predecessors) as “undulating featureless plateau”. Our own map bore a single pencilled annotation. It said “Possible location of Coromandel “

I said:

“Either its Coromandel or it doesn’t exist”

“But you said that Coromandel would only be a small rock outcrop”

“If we’d known what Coromandel was we wouldntt have had to come to look for it, would we?” I said somewhat irritably for I must admit that I was considerably put out by the appearance of such a large unchartered feature in the middle of the ice cap, and had it not lain on the precise course that we had set for it, I would have been looking for another explanation myself.

We camped that morning a mile or two south of Coromandel, and the following night sledged up onto the eastern shoulder of the peak. The all-pervading plateau mist had once again set in but we couldn’t but help being impressed, there on this isolated outpost on the polar plateau. We camped on the shoulder and after supper, (it being nearly midday) the sun began to re-assert itself and the mist once again began to give up its secrets.

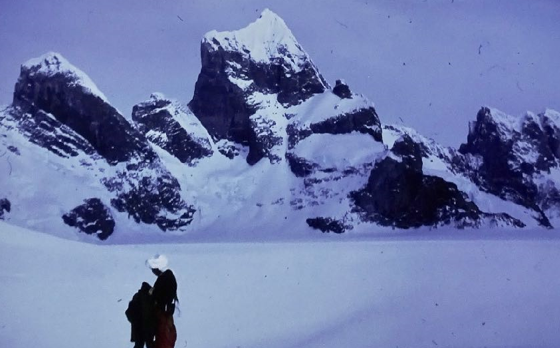

“I think I had better go up to the summit while there’s a chance of seeing something” I said to Drummy, “If this mist really sets in we could be here for weeks”.

We were fairly confident that the mountains on both sides of the plateau would be visible from the summit, but we couldn’t leave until we had made sure. I clambered out into the glare of the sun and bidding Drummy to keep an eye on in case I disappeared into any unexpected crevasse, I set off up the snow field. I had come to enjoy these solo excursions up untrodden nunataks a great deal. For all too much of the time in the Antarctic, safety demanded that we never travelled alone, but I felt that at Coromandel in particular the isolation of the place and the vastness of the surrounding landscape could only be fully savoured on one’s own.

I was not sorry that I had come, for as I climbed the sun strengthened and soon I could see across the n and the distant range later to be called the Admiral Welsh Mountains. We were shortly to calculate the height of Mount Andrew Jackson as 3184m (10,446ft) – the highest mountain on the Antarctic Peninsula.

I climbed on snow for most of the way and then crossed for safety onto rock as I passed behind the lower peak of Coromandel and out of view of Drummy’s watchful eye, after which I joined the summit ridge that lead to a surprising sharp little rocky peak. Only now did I begin to understand the great enigma of Coromandel and why it had appeared to us so dramatically out of the mist when it had remained hidden from all other viewpoints. When Miles had called it a ruddy great 5,000 foot mountain he was technically correct (the actual height is 5,654 ft) and this was rather as it had looked from the south. Had we approached from the north we might have been less impressed because on that side the surface of the ice cap is much higher, and only a few hundred feet or so of the mountain project above it.

In fact, to the north the ice continued to rise very gently, and as far as I could tell it came to a rounded crest some ten miles away. The scale was so vast though, that it was surprisingly difficult to tell which way it sloped, and I really deduced, rather than saw, that the crest was there, because I knew that Samarkand lay not 40 miles away, yet in that direction I could see nothing until the plateau met the sky in a smooth unbroken line. From a survey point of view this was not a problem because there were plenty of peaks in the western mountains that I could see, and indeed our newly established survey station at St Valentine’s depot was just visible as a grazing ray.

What did concern me initially was the fact that I couldn’t see Fandango Rock, the outermost nunatak of the eastern mountains which we had identified from a distant oblique aerial photograph and plotted on the rough sketch map which we had made of the eastern plateau just before leaving Stonington. As it appeared to be only about seventeen miles from Coromandel we had rather been relying on this as a “stepping stone” between Coromandel and the eastern mountains. Presumably though, the “ice crest” that hid Samarkand also hid Fandango Rock.

Fortunately, while I was still searching for Fandango Rock the last patch of mist across the plateau dissolved and a low rounded feature we had just called “Snow Mound” on our map, appeared. This also seemed to be about seventeen miles from Coromandel, but as it had not appeared to sport any rock we had rejected it as a possible survey station. Now though, using binoculars, I could see there was a band of rock running up the northern crest of the hill right to the summit, and it was therefore as ideally suited for our first cross-plateau survey station as Fandango Rock.

I took a compass bearing on it, and when I had built a cairn I retraced my tracks carefully back to camp. It was 4pm. I was very tired now and although my eyes were watering from peering too long through binoculars without goggles, I was well pleased with the day’s findings. The first cross-plateau line was assured, and tomorrow we could go and establish a survey station on “Snow Mound”, which for reasons that will become apparent in the following pages, we were soon to re-christen “the elusive Pimpernel”.

Drummy was lying head to the door, one eye open faithfully covering my retreat, the other one trying to doze.

“Haven’t you had any sleep?” I asked?

“Oh yes. When I saw you on the summit I knew you would be there for a couple of hours at least on a day like this. How did it go?”

“Not bad, but we’re not going to Fandango Rock tomorrow, we’re going to ‘Snow Mound”

“Oh aye – good-oh !” said Drummy, but I think he would have said “good-oh” even if I’d said we were going to the Gulf of Tongchin!

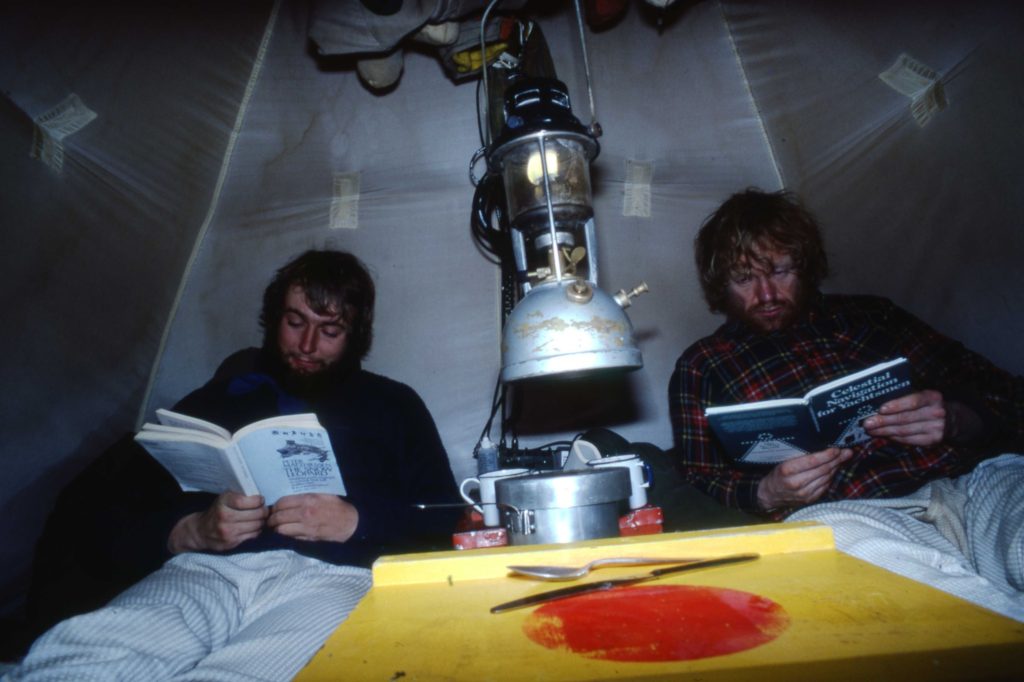

Jan 6th 1972 At Coromandel After only three hours sleep start to pack up but weather windy and snowing. Deposited survey gear (except the theodolite) as we gather Sledge Charlie haven’t moved since we last saw them and there’s no point in lugging the tellurometer and batteries etc across the plateau, Decided first to lie up.

Jan 7th In a way it was perhaps unfortunate that we had found Coromandel within a mile of its predicted position, because it had given us a false impression of the accuracy of our sketch map, and although I tried to explain to Drummy and Miles that the map of the eastern side of the plateau was only supposed to show what features were there rather than where they were, I myself had now come to the mistaken belief that “17 miles at 70 degrees magnetic” I said to Miles who was leading, as we pulled out of camp, “probably mainly downhill”

18 cold, tedious, mainly uphill, misty miles later we stopped. — “OK then. Where is it?”

We held a council of war. We could not believe that we had overshot the hill in mist for it was a sizeable feature and Miles had been leading a good course. On the other hand the visibility was at least half a mile — possibly much more – and there was no sign of Pimpernel Hill anywhere. “Your map wouldn’t be that far out would it?” Miles asked.

We travelled.one more mile and then, with much grumbling, camped. At 8 am Drummy went out to feed the dogs as the morning sun began to steal through the mist.

Suddenly he called: – “There’s your hill! We’ve overshot it”.

Miles and I stuck our heads out of the snow-sleeve entrance of the tent and although my eyes were streaming from snow-blindness again, I could clearly see the hill gleamingin the sunshine about two miles away to the southwest. Drummy took a compass bearing on it and not only set both sledge compasses to the course but actually turned the sledges on their pickets to point in the right direction. Now, whatever the weather, all we had to do was to sledge straight ahead whether we could see the nunatak or not.

Jan 8th And this is exactly what we did do. It was blowing quite hard and drifting, but it was a following wind and we had such a short distance to go that we opted to travel nonetheless. After three miles without sighting anything the veil of mist around us rolled back unexpectedly allowing us to see Coromandel in one direction and the Admiral Welsh Mountains in the other.

But of Pimpernel there was not a sign. We just could not believe it. Even accepting that the snow peak that we had seen last night was probably a mirage of one of the western mountains, we could not explain how we could not see our destination when we could see across the plateau to the mountains beyond it.

Miles suggested that as the peak which all three of us had seen yesterday did not exist, could it not be possible that the peak which I alone had seen from Coromandel did not exist either. I tried to explain that I had studied the peak through binoculars, but I donlt think I convinced anyone, perhaps not even myself! The wind was still blowing strongly, and as there was no question of turning and travelling back into it, We camped again.

Jan 9th It was an hour before midnight when the wind dropped and we set off once more towards the east side of the plateau. Again it was misty and the midnight sun wasn’t even visible. Nor did we realise how steeply we were climbing. We just knew that it seemed to be surprisingly hard work. After nine miles there was still no sign of the elusive Pimpernel and we camped again in disgust. The whole thing was a complete mystery.

To ensure that we didn’t miss a single chance of a sighting on our nunatak I had my meal outside that morning, sitting on Drummyrs sledge and peering through the mist that was again thinning with the strengthening sun. By this time visibility seemed to be at least a mile in every direction, but then again it might just as easily have been three miles. On the featureless landscape it was impossible to tell. I had never found sleeping in the glare of the day very easy, even when tired, and today I was determined not to turn in until the sun had gained some strength.

To occupy the time I thought I would take a short walk (without my skis which were helping to guy the tent), partly to gauge how good the visibility really was and partly to make sure that Pimpernel wasn’t lurking over the. brow of the next little ice rise ahead of us. After twenty minutes walking, the tent was as clear as if there was no mist at all and I was convinced that if Pimpernel was within a five miles radius I should see it. But the top of the ice rise showed nothing but the plateau rolling on. It didn’t seem to be very sensible to go any further alone, although weather-wise and crevasse-wise there was no danger here. So I turned and started retracing my footprints to the tent.

I had only just started down the slope when I looked back for a moment and stopped in my tracks. There, exactly where I had been looking five minutes before was an enormous snow cone rising out of its shroud of mist into the powder blue sky. I waited only long enough to take a compass bearing on it before literally running back to the tent to wake the others. They both came out to confirm the sighting. It appeared to be four or five miles further on, and this time we knew it was no mirage.

Jan 10th Now that we were nearly at 7,000 feet, it was really rather debatable whether there was any advantage in continuing to travel by night as it was so cold and misty from midnight onwards, and at this altitude the midday sun had its work cut out to dispose of the mist before it got round to making the surface of the snow sticky. However we set off that evening as usual.

Jan 10th Plateau(3} – Pimpernel – Phantom Rocks

Pimpernel Hill just visible as we set off with low sunlight filtering through the mist. Both drivers find the dogs going very badly but later discover that this is because we are climbing deceptively steeply. A long haul before reaching the elusive nunatak at last

It was four days and thirty two miles since I had told Miles as we left Coromandel that it looked like and easy 17 mile downhill run – and now we were over 7,000 feet!

Picketed tbe doqs and climbed to the summit by the northwest ridge which is comprised of bright red rock . .

“Scarlet Pimpernel” Miles observes.

We have crossed the plateau if nothing else.

Although the main mountain ranges of the eastern plateau were scarcely visible through the mist, it was apparent to us from the summit that, in spite of our bewildering search, we were in fact on one of the highest points of the plateau and Pimpernel was an eminently suitable position for a survey station. We therefore lost little time in concreting a brass cartridge into the bedrock of the summit (to mark the exact trig location) and building a large cairn above it as was our custom on all new trig points. In the official log of our journey Drummy wrote:

Having at last cornered the elusive Pimpernel we put a bullet in its head and buried it under a huge pile of stones to make certain the bastard didn’t get away aqainl”

Flushed with the success of having completed a task which a year ago had been considered to be impossible – that is establishing a line of inter-visible rock-based survey stations across the central Palmer land plateau — we were now eager to embark on our second objective which was to locate a peak which we had seen as a tiny speck of rock overlooking the eastern horizon when we were on Samarkand looking for

Coromandel.

The reason we wanted to find this peak was that if it was accessible as a survey station, then it should be possible to use it to measure a second tellurometer line back across the plateau to Samarkand, giving a really robust survey connection between the eastern and western side of Palmer Land. We thought that the peak was probably on a feature which we had labelled “Boomerang Ridge” on our preliminary sketch map (because of its shape), but as we could see nothing through the mist in that direction, and as the problems we had had finding Pimpernel had shown how inaccurate our sketch map was, we didn’t really know where Boomerang was, and for that matter we didn’t really know where we were either! For want of anything better, when we got back down to the dogs, we decided to go due north.

Drummy led off at a cracking pace showing clearly that it was the gradient rather than the dogs that had caused our slow approach march to Pimpernel. Now we seemed to drop away in a series of steep steps with Drummy instinctively choosing a line between major crevasse banks which we couldn’t see until we had

passed them. We were bombing down one of these steps when two nunataks loomed out of the mist on our

left proving that we had indeed crossed the plateau. We were still in sight of these phantom rocks when the surface flattened out and we decided to call it a day and camp.

Jan 12th Two days after leaving Phantom Rocks we sensed the presence of the Boomerang peaks ahead of us. The thick mist had returned and we had seen no more rock. We camped early that morning about 4 a.m. not wishing to repeat the Pimpernel debacle, and not really knowing where we needed to go. “Is there any point in pressing on tonight if the weather’s like this?” Miles asked.

Travelling in the mist, at night at that altitude had become an unrewarding, chilly experience and we had been on the verge of reverting to daytime travel since leaving Coromandel.

“Well let’s postpone alarm to 1 a.m. anyway. That should give us some midday hours on the peak if we get there”.

There was certainly no point in going on in the prevailing visibility. So, for the first time for many weeks we enjoyed a long deep sleep in the subdued light and cool temperatures of the night hours.

Jan 13th

1 a.m. The alarm rang. 1 peered out through the snow sleeve. It was misty cold and hostile. Miles stirred to ask what it was like and I told him he could go back to sleep.

3 a.m. I stirred uneasily and wondered why. Something had disturbed me, but the wind was still and there wasn’t a whimper from the dog spans. I lay for a while pondering the strange effect of the shadow of a guy rope on the tent door. Then it clicked. That’s what it was – the shadow! For the last ten days we had scarcely seen one except for the hazy blur of a distant rock through the mist. I sat bolt upright and stuck my head outside the tent. The bleak grey scenes of two hours ago had disappeared and there above was a clear blue sky and around were the high snow peaks of Boomerang Ridge – all the more beautiful because they had unveiled themselves so reluctantly and, in the end, so suddenly.

I broke the ice on the top of the porridge and started pumping up the primus. Miles heard the clatter and said dozily:

“What’s happening then?”

“It’s baby blue.” (Fid-speakfor a cloudless sky).

Drummy poked his head out of the door in disbelief with the words “go back to sleep” already forming on his lips, and said instead:

“Good Heavens! The man’s right!”

There was still not a cloud to he seen as the two teams pulled out of camp and ahead of us the sky was almost indigo down to the horizon. After travelling for over a hundred miles in almost perpetual whiteout it was a godsend to get a clearance like this at the precise moment we needed it, and the blue skies were as welcome as the return of the sun after the polar night.

We had during the last few days’ travelling dropped off the plateau and for the first hour and a half we were working hard regaining height. Boomerang Ridge like Coromandel and many of the peaks that flanked the plateau acted as a buttress to the ice so that the surface of the ice on the north and west was several hundred feet higher than that on the south and east and by the time we had regained the plateau proper, the first peak of Boomerang was only a short way above us.

The reason we had come all this way to Boomerang was to confirm that this was the peak we had seen from Samarkand poking its head above the horizon. Now that we were here we were besieged with doubts, for out to the west the ice stretched relentlessly to the blue horizon in a way that was uncomfortably familiar. There wasn’t even a hint of a distant peak. Miles said he thought that we were out of luck. Secretly so did I, but I reminded him how from Samarkand we had seen nothing until we were almost on top. “Yes” said Miles ‘but we can’t even see the high peaks beyond Samarkand”.

We picketed the dogs and started up the little peak on the west end of the ridge somewhat apprehensively, wondering what on earth we had seen from Samarkand. But hardly had we climbed a hundred feet than suddenly all the western mountain tops sprang into view. Although they were fifty miles away, we were able to identify many of them, but we just could not pick out little Samarkand which should have been somewhere in front of them.

“What do you think?” Drummy asked.

I wasn’t really happy about the place as a trig station, because as we had travelled all that way to confirm that Samarkand was visible from Boomerang, I did not want to leave without positive evidence one way or the other. Also it was becoming apparent that if we did establish a survey station in the area, it would become the pivot point of the east coast survey next year and therefore needed a three hundred and sixty degree field of view.

“I think we’d better go and climb the big fellow I said pointing to the highest peak in the range.

“Don’t you think it interesting” Miles said to Drummy “that when Tim sites a survey station that he has got to occupy himself he locates the cairn within five minutes of the sledges, yet as soon as he sites one he knows someone else will have to carry the tellurometer and batteries up to, he puts it on top of an 8,000 foot mountain!”

At the foot of the little peak which we had just climbed there was a snow pass leading through the ridges and down a steep ramp into the “crook” of the Boomerang which, after a short reconnaissance, Drummy and Miles thought was sledgeable. Drummy said it would be fast going and offered me a ride on his sledge.

“The last time I rode on your sledge was down Miles’s death slide onto the Sound” I said, “I hope it’s not going to be like that”.

This was a reference to a suicidal and near- vertical gully which Miles’s dogs had taken him down, some months before, and which Drummy and I had had to follow.

It was not like that I am glad to say, but it was a good steep sledging slope and we reached the bottom with nothing more dramatic than a double roll. We had planned to sledge from here up to a second pass below the highest peak, but as the weather was set fair and the day was still young we decided we could avoid the arduous uphill haul with the sledges by picketing them a mile or so on, and climbing the peak from there by its long south ridge. It looked an entertaining and not too serious mountaineering expedition.

When we got to the foot of the ridge we donned crampons and leaving the dogs sprawled out in the unaccustomed sunshine, we set off up towards our peak. It was not a particularly exacting climb, but it was a fine alpine ridge and there one or two uncomfortable sections where we were forced to cut steps up an iceglazed face through which little chunks of scree projected like a giant cheese-grater.

“You’d rip yourself to pieces if you fell of here” Drummy said, but it was a little further on that we nearly lost Miles when he fell through a well disguised cornice on the summit ridge and found himself with his upper half buried in snow and his lower half dangling a thousand feet above the glacier below. He managed to jam his elbows into what was left of the cornice and his whole weight was now supported on these. As, at that time Drummy and I were still negotiating the Cheese-Grater, Miles realised there was no immediate help forthcoming and gingerly extracted himself. When we arrived he was standing nonchalantly by the cornice that had so nearly precipitated his demise, warning us of is dangers.

Although Drummy and I gave it a wide berth, we could clearly see right through the hole that Miles had made, and down to the bottom of the ridge far below. It had, I think, been an unpleasantly close shave, but it was such a beautiful day that we dismissed the whole incident with a shrug of our shoulders and only realised later how serious it could have been. It was our third warning that the Antarctic lies in wait, even, perhaps especially, in the most benign of weathers.

The summit was all that we hoped it would be – a solid rock peak with good blocks for cairn building and tremendous views in all directions. It was the highest peak that any of us reached during our two years in Antarctica. For my sins I had humped the theodolite up the ridge on my back, and as soon as I had set this up we were able to identify Samarkand. The reason that we had failed to do this before was that we had thought that we were looking for a small rocky knoll on a background of distant mountain peaks, whereas in fact, Samarkand, though small in size, rose out of the plateau at considerable altitude and took its place on the skyline among the giants of the western mountains like Mount Courtauld and the Orlon Massif.

What a glorious day it was, and what a delight to see all the un-named peaks of the east paraded below us after so many days groping our way on the plateau. It was like being in a new country. We were amazed to see Pimpernel sticking out of one of the highest points on the plateau nearly forty miles away. In actual altitude it wasn’t much lower than we were, and we realised why it had been such hard work to reach. Mount Andrew Jackson to the south and the Etemity range to the north were both higher than us but it seemed to us that we had the pre-eminent position that day with low rocky peaks and nunataks spaced randomly around to the south and east. Dominating the view was the incredible escarpment of the Eland Range – twenty miles long and four thousand feet high. That day it wore a purple hue and its buttresses shimn-lered in the midday sun, We hadn’t enjoyed ourselves go rnuch all gurnmer, and the day justified the whole journey.

With inter-visible rock-based trig stations now established on Coromandel, Pimpernel, Boomerang and Samarkand, the way was now open for the west coast survey to he extended right across Palmer Land to the east coast, and our reconnaissance was complete. We would have liked to have explored the uncharted mountains and nunataks which we could see from the peak of Boomerang, but as we had heard that the Bransfield was on her way down on her maiden voyage, and as we had only six days food left, it was time to head back across the plateau to the depot we had laid on the Atlantis nunatak a month before.

We could, I suppose, have left the actual measurement of both the cross-plateau lines to next year’s survey team to do, but as I had been signatory to the report that had said it was not possible to measure any lines across the plateau, I felt the most honourable way of retracting the statement was to measure one of the lines myself!

(Miles on the summit ridge of Boomerang Peak- photo Tim Christie)

So ten days later we were sledging back up to Coromandel while sledge Charlie (now mobile again after spending nearly a fortnight lying up in bad weather) were heading hell-bent for Pimpernel.

They reached this twenty four hours after we reached Coromandel, and forty five minutes later we measured the tellurometer line between the two stations – the highest and coldest line we had measured. The distance turned out to be over twenty seven miles – ten miles greater than my original estimate!

Next day we travelled down to our St Valentines trig station while the two Pauls managed to sledge from Pimpernel to Coromandel in only 6 hours. We then measured our final line; the line between Coromandel and St Valentines. These last two tellurorneter lines, together with the associated angles, allowed the exact latitude and longitude of Coromandel and Pimpernel (and indeed all the mountains of East Palmer Land) to be calculated. As it was to achieve this that we had originally set off on the “Coromandel Journey”, it was, for me, a satisfying way to end my whole sledging and surveying experience in Antarctica.

But Drummy and Miles had another year to do!

I was still measuring angles on the St Valentines survey station when Miles called from the tent to say that a plane was on the way to fly us back to Stonington. And I was still putting the last stones on the survey cairn when the Twin Otter landed at our camp. Suddenly the “myth” days were: over and we were winging our way homewards over the open blue waters of Marguerite Bay.

FIVE FABULOUS FINNISH DAYS

John Edwards

As a Signy Fid I was extremely fortunate to be one of the few who was able to enjoy a sledging & camping trip on Coronation Island, something no longer possible in these Health and Safety conscious days when people only spend summers there without boats. However, in spite of the 3 week man-hauling expedition 4 of us enjoyed, I felt I’d missed out on the doggy-experience enjoyed by Fids at Halley or Peninsula bases, something that applies to any post-1994 Fid, as well as most of those serving on “Banana

Belt” bases.

This was something I was determined to rectify if I could and for a long time it looked like a company called Arctic Odysseys that would be the likely providers. I got an annual email and the occasional catalogue of their trips up in the Canadian Arctic where sledging on sea ice and building igloos sounded great but something – family or the expense – always seemed to get in the way.

Then by chance in 2015 1 watched an episode of “The Dog Rescuers” on BBC1 and saw how a Husky called “Tala”, who had been roaming free in Sweden for weeks, ended up being taken in by a Husky Farm in Finland. The RSPCA inspector who featured was clearly impressed with the farm set-up and I made a note of the name ‘Hetta Huskies’ so I could find out more. As in the TV programme, it shines out of their website that they really love and care about their dogs and that clinched it for me. Blow the sea ice (it might never form properly anyway!) I was going to go dog sledging for 5 days in Arctic Finland.

Marguerite Bay 52-1/4 Reunion

Topographical Survey of the Peninsula –

Topographical Survey of the Peninsula – Multiple Authors

A gathering together of yarns, stories and anecdotes specifically about the topographical survey of the Antarctic Peninsula. Really, all that had to be done was to do triangulation from the Northern tip, to South of Fossil Bluff. Easy enough. Many surveyors and GA’s were involved, and the feeling is that they probably have a story or anecdote, or two, for the years that this went on. We’ll link some of the stories already published, to this page, and add more. Tim Christie and myself (Steve W) feel the story is not so much how it got done from year to year, but why in some years, it didn’t get done at all! See the example below for a link to an existing story.

The names below are purely a starting list of those surveyors known to be involved at first thoughts – far from complete, purely as a starting point.

It’s probably best to split this into eras and areas, so here’s a starting thought (based on a quick scan of lists and already-published stories). Perhaps someone with Barbara McHugo’s book could improve on this:

The Northern Peninsula (north of Marguerite Bay)

The Northern Fjords and Adelaide

1955

Derek Searle (Horseshoe)

1956

Tom Murphy, Michael Orford (Detaille)

Derek Searle (Horseshoe)

1957

Angus Erskine, James Madell (Detaille)

Peter Gibbs, John Rothera (Horseshoe)

1958

Brian Foote, John Rothera (Detaille), Peter Forster (Horseshoe)

1961

Frank Preston & Alan Wright (Adelaide)

Colin Brown & Ken Blaiklock (Stonington)

1962

Alan Wright & David Nash

1963

David Nash & Ivor Morgan

1964

David Nash & Tony Rider

1965

Neil Marsden & Tony Rider (Stonington)

July 30th – Winter Survey Journey to Horseshoe and Detaille

BAS Archives Ref: AD9/1/1996/14/27)

On July 30th, 1965, a three-man party departed Stonington with three teams, for the purposes of establishing a topographical survey connection between Bases W (Detaille Island), Y (Horseshoe) and E (Stonington); to lay depots for the Summer Survey; visit Detaille Island Base; and if possible to visit Adelaide, to pick up “certain items” necessary to the survey.

Tony Rider (Surveyor) was driving the Spartans, Jimmy Gardner (GA) the Vikings, and John Tait (GA) the Komats. The Journey had remarkably good surfaces and mostly excellent weather during the first half of August, enabling the party to lay all the necessary depots and reach Detaille Island (Base W) three days earlier than expected. The sledgers established five (5) survey stations in preparation for the Summer Survey. Little did they expect what happened after that… Read On…

The West Coast, South from Stonington

1947

Reg Freeman & Dougie Mason (Stonington)

1958

Peter Forster & Peter Gibbs (Stonington)

1961

Howard Chapman & Bob Metcalfe (Stonington)

1962

Bob Metcalfe & Ivor Morgan (Stonington)

1965

Neil Marsden & Tony Rider (Stonington)

1966

Neil Marsden & Dick Boulding (Stonington)

1967

Dick Boulding & Derek Postlethwaite (Stonington)

1968

Derek Postlethwaite, Mike Fielding, Phil Wainwright (Stonington)

1969

Mike Fielding, Paul Bentley (Stonington)

1970

Paul Bentley &Tim Christie (Stonington)

1971

Tim Christie & Paul Gurling (Stonington)

1972

Paul Gurling & John Yates (Stonington)

1973

John Yates & Roger Scott (Stonington)

1974

Roger Scott & Richard Barrett (Stonington)

The East Coast

xxxxx

King George VI Sound and South

1970

Paul Gurling

1973

Jim Bishop

1974

Jonathan Walton & Graham Tourney

RRS Shackleton – Peter Kennett

The Southern Journey – Ian Curphey

Arrival at Triune Peaks our last survey station

Ronne Ice Shelf Oversnow Traverses – Steve Garrett

Header Photo: The Oversnow Party. L to R: Bruce Herrod, Bill Perry, Nigel Young, Ash Morton (Photo: Bruce Herrod)

Ronne Ice Shelf Oversnow Traverses (continued)

On 1st December 1982 the Chief Pilot Garry Studd decided it was time to go to the Ronne taking the overesnow party out to start distributing depots from the main depot that had been put there near to the Weddell Sea coast by RRS Bransfield in 1980, so the oversnow survey work could finally begin, lasting two summer seasons. It quickly became clear that VP-FBC’s Omega global VLF navigation system was not functioning well in the deep field as attempts to find our depots led to Russian and Argentinian depots instead. Depot duty was duly delegated to VP-FBB with the Doppler TANS onboard navigation system which proved more appropriate during the depot work and subsequent airborne geophysical surveys.

During two summer seasons a total of 3500 km of ice shelf were traversed by the oversnow party, complemented by my bit – over 14000 line-kilometres of airborne data (see following story). You can read all about it in Herrod and Garrett (1986) Geophysical Fieldwork on the Ronne Ice Shelf, Antarctica, First Break vol. 4 no. 1 pp. 9-14.

Why I Became a Fid – Jim Fellows

Why I Became a Fid – Jim Fellows

At that time, I was in my mid-twenties, and as I looked around the office at the senior designers and engineers in their late forties or early fifties, some married to tracers in the office, all having a mortgage, a couple of kids, a car, all the trappings of sedate life. All already talking about their plans when they retired. I thought that that was me in 20 years’ time. The prospect of those secure but boring 20 years did not seem very inviting. I wanted some challenge in those 20 years before settling down and planning retirement, so I used to spend my spare time with my nose in the ‘Situations Vacant’ section of the Daily Telegraph. In particular, the section advertising ‘Crown Agents for the Colonies’ vacancies, which seemed to all be in exotic-sounding places like Malaya, Fiji, Aden, Palestine, Saudi Arabia and the rest. Offering a variety of work from police posts, oil prospecting to government officers.

I do not really know what I was looking for, what I expected to find, I guess it was my own form of escapism. Then one day an advert did catch my eye and a bell rang in my head. The advert ran ‘Wanted General Assistants for Antarctic Expedition. Apply Crown Agents for the Colonies, Box Number 6357’. It went on to give the full details on how and where to apply. The advert struck a responsive chord and after 24 hours thinking it over, I replied to the newspaper advertisement. Realising that I really knew nothing of the Antarctic, other than the story of Scott’s expeditions and the 1948 film about the final expedition.

I expected that things had moved on since 1911, but I really did not know in what way, or what conditions and work tasks I was thinking of undertaking. I reasoned that it was a challenge to do something different, and after all, I did not really have a valid idea of what I was getting into when I joined the Army. I survived that.

I plunged in head first and mailed off my letter to the Crown Agents. Then to think about how to first of all break the news to my employers. After all, I would have only just completed my training contract with them. I also had to think about how I would break the news to my mother. She now saw me as settled on a good career path with the potential for a good salary in a secure occupation. I think she wanted to see all her children settled and secure, remembering the struggle she had to endure in her early married life.

My brother at that time was in the air force and stationed in Germany, so he was not around to take sides in the issue. He was more or less on the road to an early marriage, to the girl he had courted for most of his teen years. In a way I was the only ‘loose ball’ in need of counselling and guidance. My grandmother, who in my early years had always been my font for wisdom and guidance, was of mixed feelings and seemed to understand the need for a new challenge in my life. Ever the realist, she dwelled on the fact that I would again be leaving my mother on her own. Pointing out that over the past few years my mother had not had her children around her.

The first reply to my letter was simply the acknowledgement of receipt of my application. This was followed by another letter stating that I should present myself at a doctor’s address in London, for a full physical and at a designated dentist’s office for a dental check-up. The second letter further stated that subject to successfully passing these examinations, I would be called at a later date for interview.

The big day dawned and a letter arrived calling me forward for an interview. With a great deal of trepidation, I travelled down to London for the interview, not quite having any idea about what an interview at the impressive sounding Crown Agents might be like.

Whatever I expected it did not match the reality. It was soon obvious the FIDS was the ‘low man on the totem pole’ with respect to facilities allocated. All character references, proof of education, work references and any other documents were checked in the open lobby, by someone who I took to be the doorman. This with people pushing backwards and forwards, as they came into

and out of the building, whilst the nearby cage-frame elevator kept cycling up and down. The interview was conducted in a tiny room, which, I found out later, had previously been a stationary storage room. Now it was the total space allocated for the administration of FIDS. This was all the space allocated to Frank Elliot, John Green and Bill Sloman in which to conduct their interviews. From where to run the administration tasks related to FIDS, three people and the place was overcrowded. Frank’s desk was strewn with bits and pieces of stores’ items he was approving for use on the bases.

One item in particular was a string vest, and Frank remarked that his wife was wearing one to make sure they were comfortable.

Frank Elliot had done his time on a FIDS base and was able to give a very detailed description of the sort of things one would be expected to be capable of as well as a description of life on a FIDS ase. He said there are two kinds of bases, the ‘sledging survey’ bases and the offshore island bases. Most people, of course, preferred the former. Except for surveyors, people had their first year on an island base. Then if they were lucky, they would be offered a sledging base for the second year. Of course, they were opening more new bases each year. He read through my résumé and, noting that I had done a certain amount of mapping in the army, asked if I had come with the idea of applying for a surveyor position. Because if that was so, I was in for a disappointment; he emphasised that they had ‘surveyor’ applicants coming ‘out of their ears’. The vacancies they were intent on filling were ‘meteorological ‘, ‘radio operators’ and ‘diesel mechanics’. After hearing some details of the various jobs, I opted for ‘meteorological assistant’. On the question of how I would get on in confined quarters, with a small number of companions, the question was seen to have been answered by my army service record.

The interview ended with an offer of a position as a Meteorological Assistant. For which I would be required to attend a six weeks’ training course at the Air Ministry training school in Stanmore. I would also be called back to London at some future date for some dental work to insulate all my fillings so that they would still hold in at sub-zero temperatures. I left the interview with the feeling that ‘Well, you have done it now’ and there is no going back. Now you have to face the problems of telling everyone else and in particular GEC. About that time the press was becoming full with articles about the impending ‘International Geophysical Year’, which was deeply connected with activities in the Antarctic. There were stories relating to preparations for the Trans-Antarctic crossing expedition to be led by Vivian Fuchs (later Sir Vivian Fuchs) with Sir Edmund Hillary as co-leader. This expedition was to cross via the South Pole from one side of the Antarctic Continent to the other and gave the newspapers a birthday of news to exploit.

So, it was at a time when the newspapers were full of Antarctic stories that I chose to go to the GEC personnel manager and announce that I would be shortly be leaving for an expedition to the Antarctic; that I would be away for slightly over two years. Whether or not he thought that I was going with the TAE, or something to do with the International Geophysical year, I have no way of knowing; instead of a reproach for what I was planning, he enthused about what an exciting opportunity it was for me.

In no time at all it was all around the site and I became a short-term celebrity. On the question of notice there was no problem. Although I would have to re-apply for employment, they saw no reason why I would not be offered a position back in the design office on my return from Antarctica. My mother took a more realistic approach, being concerned with how I would survive all that cold. What if anything happened and no ships could get through the ice? She need not have worried on that count, the ships only visited once a year.

At Stanmore I was installed in a B&B accommodation together with two other FIDS, Cecil Scotland and George Larmour, both from Northern Ireland, all of us destined for the Meteorological Training College at Stanmore. The course was intensive and thorough, concentrating on the practical tasks we were expected to perform, rather than any programme of extensive theory. For us it was basic theory and a lot of practical practice.

After the course was over and I had gotten my teeth fillings attended to, there was still a few weeks before the scheduled sailing for Antarctica. As I was now on the FIDS payroll, it was decided to assign me to the meteorological office at Birmingham Airport, to get some hands on experience. The work there was reading temperatures, pressures and humidity every three hours and filling out weather statistics sheets. My previous army experience with maps and plotting was put to good use, by having me plot out regular temperature and pressure charts for the area that the airport office covered. These charts were used by the weather forecasters and had to be updated on a regular basis. Plotting temperature and pressure isobars was not so different from plotting elevation contours in the army, so I soon settled down to the routine.

The day before the scheduled sailing, I caught the 20 minutes past midnight train to Southampton and was at the dock gates by about eight am the following morning. At the dock gates, I inquired as to how I would identify the John Biscoe and was told, “It’s easy, mate; all you got to do is go straight down there. At the quayside look for a ship with a covered in ‘Crow’s Nest’ on the mast.” I proceeded as directed and as I looked to the right, along the quayside, I saw this moderate-sized ship with the type of ‘Crow’s Nest’ described. Whilst I was musing over the idea that life could be comfortable on a ship of this size, the voice of the gateman interrupted my thoughts with a cry of, “Not there, mate, around to your left.” I moved along the quayside to my left and at first could see no other ship.

Then I noticed a mast just about sticking above the quayside. On closer examination, there was an enclosed Crow’s Nest attached to this mast. Walking to the edge of the quayside, I looked over, there below was the John Biscoe. She had been built as a submarine net layer for service on the west coast of Canada. There lay the ‘big ship’ I was sailing south on, 194 feet in length and 37 feet wide. A wooden-hulled ship that had been designed to drag a heavy anti-submarine net across wide harbour entrances. Not exactly what one would expect for crossing the roaring forties. In fact, I rather felt she would bob about like a cork when in any rough seas.

Instead of the expected gangway up on to the ship’s deck, this one had one walking steeply down to the deck level of a ship, whose deck was lying well below the top of the quayside. I went on-board and introduced myself to one of the FIDS who had boarded the day before. He showed me the way down to the bunk area, which lay along the beam of the ship. The area had four tiers of two bunks on either side of a narrow gangway, with very little space to stow personal belongings. After stowing my things on an empty bunk space, I was then lead to what was described as ‘the FIDS lounge’, equipped with a few padded easy chairs. This lounge also boasted two rows of seats, one on either side of a long mess table, which occupied the majority of the space. It was obviously for dining, and thinking about the number of sleeping bunks, I figured that space in this lounge would be at a premium, except for those sitting at the mess table. That was October 10th, and I then found to my dismay that the ship was not due to sail until the 12th.

After introducing myself to more of the FIDS, who were in the lounge, their opinion seemed to be that the majority of people who had already arrived were either up on deck or had gone ashore to kill time before sailing. The evening was spent getting to know each other, that is, those who had already joined the ship. It seemed there were still several people yet to arrive on board. The following day I joined a group who had decided to spend the day onshore, taking in the sites of Southampton, such as they were in 1955. Then the day for sailing dawned at last; we spent the morning ashore, at least until noon. We had to be back on board, in time to get our briefing from the captain.

On that trip down, there were many I would be on base with. These I would get to know extremely well. There were others, which after they landed in the Falkland Islands, I would not see again for years. There were Percy Guyver, John Smith, Colin Johnstone, Len Fox, Pete Bunch, Stan Ward, Joe Axtel, Len Maloney, Gordon Farqhuar, Wally Herbert, Colin Clements, George Larmour, Cecil Scotland, Eric Broome and a host of others, whose names have passed out of my memory, I am afraid.

On deck were all the trappings for a newsworthy sailing, supported by a host of reporters representing both local and national newspapers. It was no surprise to learn that my photograph had appeared in a local newspaper with a report about my departure, to spend two and a half years away from home on an expedition to Antarctica. I am sure the others on board were equally covered, and finally, Lord Munster gave a farewell speech, on behalf of the secretary of state and with that we were ready to sail.

First, we had to be briefed on safety procedures at sea. We were then advised that because we would have so much spare time on our hands, it was planned that we would spend some of our time each day doing ship’s chores. Work, such as painting, sharing watches at the ‘wheel’ with the ship’s crew and helping with the preparation of vegetables needed by the galley (peeling potatoes). Cecil Scotland was to be the senior FID and would act as the liaison between the ship’s officers and FIDS personnel. It was his job to make up the rosters of people for the daily work-tasks. Daily tasks would be assigned by the Bosun to the names on the roster, with the exception of the ‘wheel watches’, which were listed by name on Cecil’s list.

We set sail on the evening tide after a bright but cold sunny day. Afterwards, we retired to the FIDS mess/lounge for our first meal on board, which passed off smoothly even though crowded. I suspect the ship’s steward was exhausted by the time he had finished serving that lot. After the meal some retired to a quieter corner in order to write a letter home, to be posted at the first port of call, or sat talking about what was ahead of them all. Some had direct knowledge, others quoted pages from Kevin Walton’s book ‘Two Years in the Antarctic’. Others went on deck to unwind, since there was no way they could sleep after all the excitement of the departure.

(Jim wintered at Deception Island in 1956, and then transferred to Horseshoe Island in 1957) Read on….

Why I became a FID – Dave Rowley

Why I became a FID (continued)

In those times , flying jobs were hard to come by, and I was wary about jeopardising my current one but thought nothing to lose, do the interview! I drove my battered old Ford Consul Mk 1 from Goodwood to Gillingham street on a beautiful July morning, and that was the start.

On my interview day, there must have been at least 20 of us hanging around all day . There were unemployed airline pilots, ex RAF, and an Australian bush pilot. I felt least qualified out of the lot. Not only that, I was the last interviewee at 5:00 in the afternoon, having arrived with the rest at nine in the morning. The interview board were Bunny Fuchs, Derek Gipps, Paul Whiteman and Bill Sloman, and it lasted about half an hour. Their eyes lit up when I told them that I learnt to fly in Singapore in the fifties, and used to fly into unmanned jungle airstrips in Malaya to deliver the monthly payroll to remote pineapple plantations, in order to build up my flying hours toward my commercial pilots licence. That must have come as a surprise to them, because it wasn’t in my CV .

It does not embarrass me to say, that when offered the job, I turned it down. Twice. After Bill Sloman’s letter saying that the job was mine, with less than a months notice to give to my employers at Goodwood School Of Flying, with forfeit of that month’s salary. It came as a “bolt out of the blue”, and I was convinced that I had bitten off more than I could chew. My speciality as an advanced flying instructor was teaching aerobatics, which I thought I was going to miss with all the associated social life!

I rang Bill to say that I had changed my mind, having just become engaged, which was true, but Bill wouldn’t have any of it. We talked for half an hour, and I said that I would think it over. My prospective wife wasn’t happy, but I convinced her that it was only a one-year probational contract, which made her soften a bit. My fellow instructors thought it was crazy.

Bill phoned me the next day. Again we talked for best part of an hour and he gently talked me round, putting on the pressure by saying that my airline tickets to Toronto were there in HQ. I learnt later that was a con. I rang him the next day to say not for me, and again, he talked me round.

The following month saw me on the induction course in Cambridge with Bert Conchie , Dave Brown and Ron Ward. We bonded instantly , having been in the RAF myself as an airframe fitter and Bert starting off as an instrument fitter.

Anyway , I went to DHC Toronto full of doubt and trepidation tasked with liaising between DHC and HQ with taking VP-FAP out of mothballs, and the handover of VP-FAM and completing the Twotter/Turbo Beaver conversion courses. At the end of that two weeks in Toronto, all my doubts and uncertainties evaporated and the rest is history. I feel incredibly privileged to have worked with you blokes and the brilliant army engineers, and to have experienced the most rewarding flying in the world, plus of course the gash runs! After FIDS, I had 23 years of mind numbing airline flying before retirement, with only the occasional engine disintegration, depressurisation or landing in 150 metres of freezing fog, to break the monotony.

Dave Rowley – Pilot – BAS Air Unit – 1969 to 1974

Why I Became a Fid – Dave Rowley

Why I became a FID (continued)

In those times , flying jobs were hard to come by, and I was wary about jeopardising my current one but thought nothing to lose, do the interview! I drove my battered old Ford Consul Mk 1 from Goodwood to Gillingham street on a beautiful July morning, and that was the start.

On my interview day, there must have been at least 20 of us hanging around all day. There were unemployed airline pilots, ex RAF, and an Australian bush pilot. I felt least qualified out of the lot. Not only that, I was the last interviewee at 5:00 in the afternoon, having arrived with the rest at nine in the morning. The interview board were Bunny Fuchs, Derek Gipps, Paul Whiteman and Bill Sloman, and it lasted about half an hour. Their eyes lit up when I told them that I learnt to fly in Singapore in the fifties, and used to fly into unmanned jungle airstrips in Malaya to deliver the monthly payroll to remote pineapple plantations, in order to build up my flying hours toward my commercial pilots licence. That must have come as a surprise to them, because it wasn’t in my CV .

It does not embarrass me to say, that when offered the job, I turned it down. Twice. After Bill Sloman’s letter saying that the job was mine, with less than a months notice to give to my employers at Goodwood School Of Flying, with forfeit of that month’s salary. It came as a “bolt out of the blue”, and I was convinced that I had bitten off more than I could chew. My speciality as an advanced flying instructor was teaching aerobatics, which I thought I was going to miss with all the associated social life!

I rang Bill to say that I had changed my mind, having just become engaged, which was true, but Bill wouldn’t have any of it. We talked for half an hour, and I said that I would think it over. My prospective wife wasn’t happy, but I convinced her that it was only a one-year probational contract, which made her soften a bit. My fellow instructors thought it was crazy.

Bill phoned me the next day. Again we talked for best part of an hour and he gently talked me round, putting on the pressure by saying that my airline tickets to Toronto were there in HQ. I learnt later that was a con. I rang him the next day to say not for me, and again, he talked me round.

The following month saw me on the induction course in Cambridge with Bert Conchie , Dave Brown and Ron Ward. We bonded instantly , having been in the RAF myself as an airframe fitter and Bert starting off as an instrument fitter.

Anyway , I went to DHC Toronto full of doubt and trepidation tasked with liaising between DHC and HQ with taking VP-FAP out of mothballs, and the handover of VP-FAM and completing the Twotter/Turbo Beaver conversion courses. At the end of that two weeks in Toronto, all my doubts and uncertainties evaporated and the rest is history. I feel incredibly privileged to have worked with you blokes and the brilliant army engineers, and to have experienced the most rewarding flying in the world, plus of course the gash runs! After FIDS, I had 23 years of mind numbing airline flying before retirement, with only the occasional engine disintegration, depressurisation or landing in 150 metres of freezing fog, to break the monotony.

Dave Rowley – Pilot – BAS Air Unit – 1969 to 1974