Culinary arts at Stonington – Peter Kennett

(All photos by Peter Kennett, unless otherwise stated)

The ways in which most bases organised their cooking will be familiar to old Fids, but it might be of interest to the younger generation to know how we coped at Stonington in the 1960s, which was probably typical. Like most bases, we had no professional cook, but took it in turns to provide for the members, numbering up to 12 when nobody was out sledging. Our method was for the cook to serve a three day stint.

Having largely had my food provided for in my student days, my only experience of cooking was at Scout camps, where one could often get away with murder! Catering for 11 others, from whom one could not escape if things went wrong, was rather different. Some cooks were so well organised that they could relax in between meal times or carry out other jobs, but for me it became almost a full time occupation for those three days, even allowing for the help of the “gash hand” rota, where there was always somebody else to top up the melt tank with snow blocks, bring in more anthracite for the Esse stove and assist with washing up.

Continued from Stonington Page, 1963

The usual routine consisted of breakfast; morning “smoko”; lunch; afternoon smoko; evening meal. After that, if anyone was still hungry, the kitchen was available for “supper rats”. Breakfast was usually cereals or porridge, then fry ups. Lunch was soup and a pudding and the evening meal was main course and a pudding. For smoko (a Falkland Island term), the coffee percolator would have been on the stove for hours with the coffee getting less and less healthy as it became thicker, but it was always accompanied by freshly made biscuits or scones. We made fresh bread every day, by making up enough dough for the three days, working up and baking a third of it and leaving the rest in the cold ready for the other two days.

We were very well supplied with a range of dried and tinned foods, plus a mutton carcase or two when the ship relieved the base after the winter. Our “Minister of Food” was Dave Beynon who kept the inventory, so that we knew what we had and so that supplies could be ordered for the next season. Dave’s typed report included the phrase, “The only item in short supply was the pickled onion”, and debate raged about the correct grammatical use of the singular or plural term!

Menus were decided by the cook, depending on the available recipe books, which included Mrs Beaton and Gerry Cutland’s “Fit for a Fid”. My mother had written out a number of her favourite recipes, including her classic fruit cake, which came in handy when it was someone’s birthday.

As an example of a menu, on my first day as cook I gave them my own tomato soup and toad-in-the-hole for lunch, Cornish pasties and apple crumble for dinner. I also made flapjack and buns for goodies and managed to turn out a couple of cakes as well. The next day wasn’t so successful, as I had intended to make bread pudding to slice up for afternoon smoko, but followed the wrong recipe and ended up with bread and butter pudding, which is not so easy to eat out of one’s fingers!

Generally, if someone had tried hard to provide a varied menu, even if it didn’t turn out too well, it was appreciated more than if the cook had taken the easy option and had simply made Creamy Fish Pie. Somebody had read that when a Roman emperor returned to Rome after some major victory, he would be awarded a “Triumph”, so it became our custom to give a loud thumbs up Triumph for a good effort. The most memorable Triumph was awarded to Ian McMorrin who laboured hard to turn out a Swiss roll, but left out the baking powder, so that it was no more than about 3 cm in diameter! At an early stage, I was awarded a Triumph for chocolate eclairs, but this turned out to be a mixed blessing, since they were demanded when I was next on cook and they were a real fiddle to make. Thus a number of people developed their own specialities, including Mike Fleet’s “cream” doughnuts (with artificial cream made from margarine), and, if memory serves me correctly, Ben Hodges for mince pies.

Meals were mostly served on time, although on very calm days the stove would not “pull” sufficiently to get up to temperature and the cook could be heard furiously pumping up a Primus in order to boil water for cooking (no electric kettles in those days).

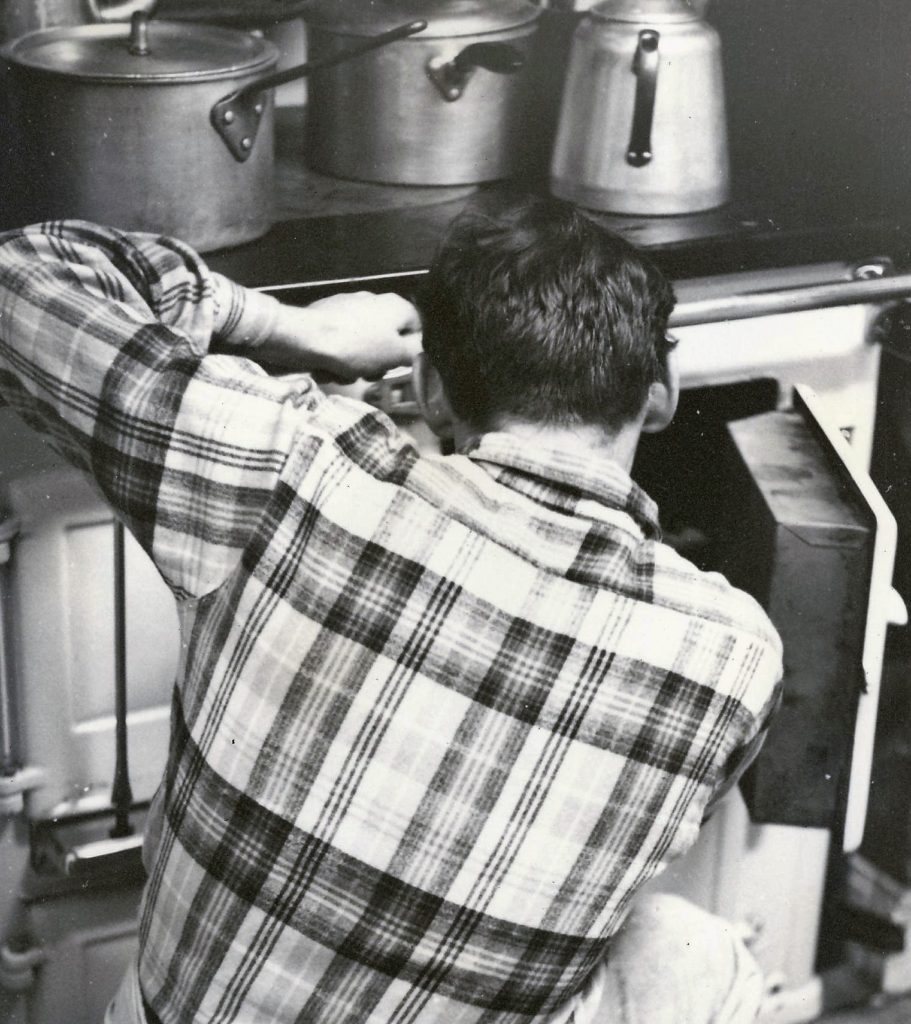

I found out later that most proud chefs had privately taken a photo of themselves in the kitchen, with an array of delicious looking cooking which “just happened” to be airing in the background! Before the days of “selfies” this entailed setting up the camera with the delayed action and using a precious flashbulb, with no guarantee that the slide had come out, until it was processed back in the U.K.

Although food was plentiful on base, we welcomed anything which we could source from our surroundings. Given that we had to shoot seals for the dogs, we made good use of the seal liver and steak and sometimes the hearts, which must have boosted our intake of vitamins, as well as being very tasty. The whole process of shooting with the .303 rifle and gutting was highly unpleasant, but we had the consolation of knowing that the seal was normally killed with one shot and did not suffer for long.

Wildlife was scarce in the winter, but skuas continued to raid the seal pile, so from time to time they would be shot with the .22 rifle or caught with a baited noose by Mike Fleet. They were mostly roasted, but on one occasion I decided to make them into a pie. The Victorian Mrs Beaton had no recipe for Skua Pie, but she did have one for Pigeon Pie, where the chef was instructed to leave the legs sticking out of the piecrust. I did this with the skuas, but their huge webbed feet were considerably larger than those of a pigeon, so they tended to dominate the table. I forgot to take a photo – did anyone else?

Mike Fleet had done some river fishing at home and tried out his skills at Stonington, sitting for hours on an empty box, fishing through holes in the sea ice, Innuit fashion. Most of the catch consisted of Notothenia, an ugly but tasty fish, once it had been skinned and filleted. He thus managed to supply me with about 40 small fish during one of my turns as cook, which were well received when fried in batter, although trying to make chips with powdered potato was quite a challenge. Years later, during a tour of BAS H.Q. at Cambridge, we were shown round the cold water tanks, where a number of friendly Notothenia were coming to the surface to greet us. Some of us audibly began to discuss their potential as lunch, to the horror of the current marine biologists who are not allowed to eat them!

Like most bases, the Midwinter feast was a highlight of the winter, and much effort went into it. For 19th June my diary recorded, “All the preparations for Midwinter’s are now well underway – Ron wrote out the menu cards today, Mike unpacked the iced cake which his mother had sent down, Dave made the puff pastry and Ian started to think about the decorations!” I had already made individual photo cards for the backs of the menus, by superimposing various subjects onto portraits of each member of base, and somehow keeping the results hidden from everyone else – which was difficult because we invariably held a “wet salon” session whereby anyone could inspect the results of someone’s efforts in the darkroom. On 21st June itself, the duty cook, Ben Hodges, agreed to swop to undertaking gash hand duties, so that two of our resident Scotsmen, Ron Tindal and George McLeod, could take it on themselves to provide the repast.

When the evening meal was ready everyone disappeared to spruce up, to emerge later in collar and tie and even wearing shoes – which barely went on one’s feet after flopping about in slippers or moccasins for so long. To quote from the diary again, “We kicked off with Crail Crab – a mixture of shrimps and crab in aspic jelly. This was followed by chicken soup, then the main course, comprising our carefully conserved mutton (‘Stanley Turkey’), baked ham, carrots in cheese sauce and sprouts. Sweet was a splendid trifle, fruit jelly and ice cream. Then those of us who had any room left downed a cup of coffee and a glass of port or liqueurs according to taste. The menu cards caused a great deal of amusement and were duly passed round for signing.

Of course, the whole reason for being at Stonington was to equip us for the field work, both locally in winter and, for six of us, four months in the summer on the Larsen Ice Shelf. In retrospect, the “flesh pots” lifestyle on base must have set us up well for the monotonous diet of the sledging rations, but that’s another story!

Peter Kennett – Geophysicist – Stonington 1963