Eliasoneering – in theory and in practice! – Peter Kennett

Photographs are by Peter Kennett, unless otherwise stated, or unless inadvertently mixed up with the communal photographic processing on base!

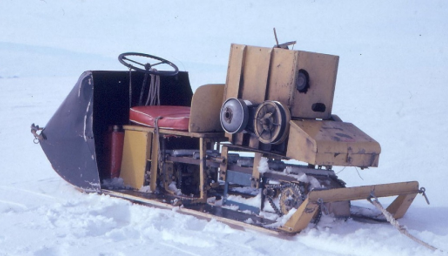

The transmission seemed to me to be unnecessarily complex, involving a clutch, a V-belt, axles taking the power across the vehicle and then back again, before finally connecting with the track. There was a seat with a steering wheel, for those brave enough to sit on it through crevassed areas, or the steering skis could be operated from behind by the attachment of long cords. This was a lot safer, as later experience showed, but was actually impracticable where it was most needed – in crevassed glaciers – since sufficient finesse of steering could not be achieved by remote control.

Our first working experience of the Eliason came soon after our arrival at Stonington. The intention had been for the 6 members of the East Coast (Larsen Ice Shelf) Party to be flown across the Peninsula to its working area for the summer, and then airlifted out to Stonington for the winter. The two single-engined Otters had laid large depots in readiness, at Churchill Peninsula and Whirlwind Inlet, but after this, the aircraft became unserviceable for much of the time, so we had to fend for ourselves. This meant that a further depot of about 3700 lbs (1.68 tonnes) had to be laid overland at Three Slice Nunatak in the autumn, to support the journeys the following spring.

Initially, we were guided by a paper by Charles Swithinbank in the Polar Record (Vol 11.72 1962), which put the Eliason into a favourable light. It soon became apparent, however, that Swithinbank had experienced far better fuel consumption and less mechanical failure than rapidly became our experience.

In theory, each Eliason could pull two 12 foot Nansen sledges, with a total load of nearly a tonne. The depot-laying trip therefore started out up the North-East Glacier, which at that time was linked to Stonington Island by an accessible ice ramp. Its steepness meant that we had to relay each sledge up, as the three dog teams went hurtling by, with Jon Clennell, Ben Hodges and George McLeod. Once on a gentler gradient, however, the two sledges could be towed at one go.

It wasn’t too long before we found our first crevasses – or, rather, the leading Eliason did. We soon found that the back of the machine tended to drop into the crevasse, as a snow bridge gave way, but that the track would then bite into the further lip of the crevasse and throw the whole machine up into the air. If it had enough momentum, it would then straighten itself up and continue pulling, until the sledges and their terrified driver were safely over!

The route which we were using was pioneered in the 1940s, and used both by the Americans of Finne Ronne’s expedition to Stonington Island and by the FIDS base, sited only a few hundred yards away. After a few miles, the gentle slopes of the glacier gave way to the notorious Sodabread Slope, leading towards the plateau at an average gradient of 1 in 2½. After lying up for bad weather, we set about lifting the depot load up the steep slope. The surface was covered in deep soft snow, and we tried breaking track with an unladen Eliason. Eventually, with all six of us pushing, we made it to the top, although not without some misgivings about the clutch, which was smelling horribly and got too hot to touch. After a quick look round we all somehow got onto the Eliason and I drove off down the hill at considerable speed!

After much experimentation, we found that the most efficient way of getting the supplies to the top of Sodabread was to lash four ration boxes onto the seat of each Eliason and then to push or run alongside, up the slope.

Gradually the surface improved to the point where it was virtually impossible to stop it running away on the descent, and so both passengers with each machine flung themselves onto the rope at the back and were dragged along as anchors! The first of many mechanical failures happened during this process, when the throttle cable on one machine broke and it had to be controlled with one arm behind the driver’s back, which was very awkward.

Thanks to bad weather, the party returned to base to regroup. On the way home, the other throttle cable broke and one machine stopped altogether, because of icing around the carburettor, under conditions of driving wet drift snow. We didn’t dare stop the functioning Eliason, but loaded the defective one onto a sledge and set off with the one serviceable machine towing all four sledges. Luckily, it was all downhill, but I had to reach the throttle behind my back and hold it open for several hours, resulting in mild frostbite!

Once back at Stonington, we took both the machines into the old rusting Nissen hut – a relic of the 1940s – and spent a day or two boxing-in the engines with plywood to keep the drift at bay. With no heating, and with frostbite developing in my fingertips, it was unpleasant, but proved worthwhile.

Work on the establishing the depot resumed a few days later, with one dog team (Moomins with Ben and George) and the two Eliasons doing most of the lifting of stores to the plateau top at around 1700 metres. On the steepest slopes every box had to be carried up on back- packs. There was a noticeable reduction in power from the Briggs and Stratton engines, owing to the altitude. Meanwhile a reconnaissance party of three men (Ian McMorrin, Ron Tindal and Ralph Horne) with the Spartans and Giants had set off to find a route through the treacherous crevasse belts of Bill’s Gulch, to enable us to reach the Larsen Ice Shelf below. Once the route was established the whole team reassembled to ferry the stores down to the shelf ice, mostly perforce sitting on the machines rather than steering by remote control, because of the intricacy of the route through the crevasses. The route across the undulating shelf ice to the depot site at Three Slice Nunatak was only about 20 miles but for much of the way, loads had to be relayed.

The Eliasons varied vastly in their performance, ranging from relatively smooth running with huge loads on good level surfaces, to digging themselves in and stopping in deep soft snow. Much relaying of sledges was needed. Starting the machines in the morning at temperatures as low as -35oC was fraught with difficulty, so we tied lampwick around the air intakes in order to pre-heat the air with meths. On one memorable occasion, once mine was going nicely, I decided to take it out for a warming-up run before hitching onto a sledge. It had just reached the stage where it was running really well, when I turned a corner too sharply, hit sastrugi which nearly overturned the machine, and was thrown off. The next thing I knew, the Eliason was rapidly making off towards the horizon. Mike valiantly gave chase on his, but it was no match for the unladen machine and he soon returned. I then refuelled and set out following the trail of my vehicle. The trail led up towards Francis Island, then round in a big arc towards the mainland and went so close that I began to think it must have gone down a crevasse. Fortunately, it had doubled back and I eventually found it after an hour and a half and probably 10 miles of very cold driving. When I arrived I felt that my fingers had been nipped and sure enough every one of them was white, so I held them over the exhaust until they came back again. Then I set off back to camp, trying to drive two machines at once, and arrived after another hour and a half, frozen stiff.

The return journey to base with light loads was, understandably, considerably quicker than the outward trip, but was not without its excitement. Sledging back up Bill’s Gulch, the three dog teams led, followed by Mike Fleet with one Eliason and then me, as tail-end Charlie, both of us driving from the seat, rather than by remote control. We were each towing two sledges, and Tony Marsh was riding on or walking alongside the first one behind me. We were going along very nicely when, all of a sudden, the machine stopped with a jerk. Simultaneously I heard a crump behind me and turned round to find a gaping hole three metres wide and twenty metres long with the two sledges jack-knifed across it, and no sign of Tony! The first thing I did was to bellow to the others up ahead, then picketed the Eliason and gingerly walked back to see what had happened to Tony. I was greatly relieved to see him hanging about two metres down, unhurt, although he was not wearing his safety harness but was hanging on to the towing pennant which linked the two sledges. He couldn’t scramble out without help and all I could do was to lower him a foot sling and wait until the others came up. Of course they came with all the tackle and soon had the sledges picketed. Meanwhile Tony summoned the energy to climb out onto the sledge and thus to safety. As soon as he was out, Mike took a photo of the sledges on his Minolta 16mm camera which he had in his pocket, and then helped pull the back sledge away from the hole and across the crevasse by a firmer bridge a few yards further down.

After this, it was relatively plain sailing, although we had to lie up for longer than intended and went on to short rations for a day or two, just in case.

My diary records a constant succession of mechanical failures on each machine, throughout the trip, partly owing to the hammering we were obliged to give them over the rough terrain. However, some failures appeared to be due to faulty design or manufacture. Some of the fractured castings showed air bubbles in the metal; the track assembly on one Eliason had been fitted the opposite way from the other one, so one must have been incorrect; links in the motor bike chains which drove the track, broke repeatedly, and various other components either sheared off, or fell off, owing to the incessant vibration. Repairs under cold conditions could be unpleasant, especially when trying to rivet new chain links, using a geological hammer! Very few tools and spares were supplied with the Eliasons, so a lot of improvisation was necessary, much of it supervised by the ever-practical Ron Tindal. During the course of the trip, the Falklands Islands Broadcasting Service put out a record request programme, so we requested Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen, for the two professional mechanics at Adelaide, Dick Palmer and Ron Gill!

In spite of all the problems, most reluctantly agreed that the Eliasons had played a very useful role in enabling such a large depot to be laid, across the plateau and out over the shelf, ready for the working season the following spring and summer.

Once back at base, we had the winter in which to lick our wounds. It was obvious that neither Eliason would be fit for the spring journey across the plateau, even though we hoped to use an easier, but more circuitous route, up the Snowshoe Glacier, and thus avoid the terrors of Bill’s Gulch.

I stripped down both machines in the Nissen hut, with Tilley lamps for light (and a bit of warmth!), and did my best to renovate them. The engines themselves were in good condition and didn’t really need the decoking which Ron and I gave them. (Reassembling each side-valve engine was tricky – until our dentist, Dave Beynon, announced that his work involved fiddling about in restricted spaces and came over to give a hand, although I don’t recall if he actually used his dentist’s tools!).

Although both engines were in good shape, it was very clear that many components of the motor sledges were broken beyond repair. We had no welding equipment at Stonington, and without this we could not fabricate replacement frames for the chassis. In view of this, it was arranged that Dick Palmer would travel across from Adelaide Island in the winter, with spare parts which he had manufactured there. The intention was for one Adelaide-based Eliason and a dog team to come across, once the sea ice was safe, but in the event the Eliason broke down shortly after setting out, so Dick had to travel by dog sledge. Adelaide personnel brought him to Blaiklock Island, where he and the gear were transferred to Stonington teams. Dick was an Army Corporal, on loan to BAS, and his idea of a good time was to work in a nice heated workshop and to travel about in the snug cabin of a Muskeg! As he and his companions approached Stonington in the depths of the winter, in August, he fell in an open lead, and entered the hut, creaking with ice in his clothing!

Dick, with me assisting and learning, spent the best part of a fortnight, replacing much of the frame of each Eliasons, and generally trying to bring them back to working order. To test one out, he and Mike Fleet tried to take a drum of Avgas up to the aircraft depot on the glacier, but bogged down innumerable times, so gave it up. Dick came into the hut muttering, “If I ever again say anything in favour of the Eliasons, just hit me over the head with something hard!” In the midst of all this, the base received a telegram from Johnny Green saying, in effect, “Owing to the emphasis now being placed on mechanical transport by BAS Office, it has been decided to stop dog breeding, except for the maintenance of three teams at Halley Bay”. Suggestions as to what to do with the offending telegram ranged from pinning it up so that the dogs could read it and act accordingly, or throwing darts at it! In the end, Ben calmly filed it with his dog report, to keep it out of sight. Shortly afterwards, Hecate of the Trogs gave birth to pups, so she obviously hadn’t seen the message!

After a delay of a month, for bad weather and poor ice conditions, the six members of the East Coast Party finally set out on 4th October, with others in support as far as the Snowshoe Glacier. We crossed the plateau via the Traffic Circle, and travelled by a circuitous route to our depot at Three Slice Nunatak. We stayed in the field continually, until our return to base on 25th January.

At Three Slice, we split into two groups – Sledge A consisting of Ben and Ron with the Moomins and the Giants, plus Mike Fleet with one Eliason: Sledge B comprising Ian with the Spartans, plus Tony and me with the other machine. Half way though, Mike and Tony swopped places, in order to visit other parts of their geological patch.

During the season, Sledge A travelled north as far as Cape Fairweather and Sledge B to Cape Disappointment, carrying out geological and geophysical work, and enhancing the rather sketchy topographic maps which existed at that time. Work included surveying up and down several of the glaciers which feed into the shelf from the Peninsula, as well as criss-crossing the inlets on shelf ice, for geophysical surveying, to try to determine the thickness of the ice.

The Eliasons behaved much as they had done during the autumn depot laying trip, except for the terrain being less punishing, and mending broken track chain links was less unpleasant in the milder summer temperatures. As before, on good even surfaces they could pull heavy loads at a good speed of up to 4 mph, but all too often on soft snow they would dig themselves into holes and require much heaving and pushing to get them out again, with occasional relaying of sledges. Mostly, the dogs led, but at times when the Eliason was bogging down, in addition to their own load, the dogs took the second sledge from the machine, which then broke trail with a light load. Breakdowns were similar to the autumn, with a number of metal parts fracturing or bending, in spite of Dick’s sterling work at Stonington. Chain links needed replacing quite often and we were all too aware of the shortage of spares.

We kept a log of fuel consumption during the whole year. At best, on excellent surfaces in summer, the vehicles returned a figure of 9.3 miles per gallon (mpg). In colder weather the best we could hope for was about 6 mpg. Given that a lot of relaying was done on bad surfaces, involving covering the same ground three times, consumption increased to a mere 4.3 mpg overall for direct miles travelled.-

In total over the year, Eliason No: 2000 travelled 1058 miles and No: 2001 covered 670 miles. Why the difference? What happened to them in the end?

My Eliason was No: 2001, and together with Ian and Tony, we thought we had spotted an easy route up onto the plateau, up the gentle slopes of Philippi Rise, above Adie Inlet, where nobody had ever been before. So, on 10th November, 1963 we set off. Surfaces were soft, and the Eliason gave considerable mechanical trouble, so we took four hours to cover five miles and camped, to re-rivet the track and carry out other adjustments. The following day, we set off in the cool of the evening with high hopes, but had only gone 200 yards before the Eliason expired with a loud clang and settled down into the snow. This proved to be its final resting place: the track had broken in three places and we had already exhausted our meagre supply of spares, so we had no choice but to leave it pointing futilely up the hill.

Up to this point, the route had “gone” very well: we had attained a height of over 600 metres, with every prospect of making the remaining 400 metres to the plateau at this latitude. The loss of the Eliason meant that one dog team would have a load of 1600lbs imposed on it, so continuation of the journey would have been impossible. We therefore collected the tools and useful spares and headed back down the slope.

Now then, have I been dreaming, or did I read that someone has discovered the remains of this Eliason recently? Answers on a postcard…….!

Eliason No: 2000 fared rather better. Shortly after the abortive attempt on the plateau, the two sledge parties met at the Churchill Peninsula depot and swopped geologists. So now, Sledge A consisted of Ron and Ben with the Giants and the Moomins and Tony; whilst Sledge B regrouped with Ian and the Spartans, plus Mike Fleet with the Eliason and myself.

We spent the rest of November working around Cape Disappointment and the Starbuck and Stubb Glaciers, and were lying up on 22nd when we just happened to tune in to the BBC, to hear the shocking news of the assassination of President JF Kennedy.

We were supposed to be flown out from the Churchill Peninsula depot, but either the aircraft were unserviceable, or the weather wasn’t fit, so we endured long lie-ups, interspersed with local trips for much of December.

Eventually, we were told to sledge down to Three Slice Nunatak, for a final attempt by the aircraft; otherwise to sledge back home over the plateau, following our autumn depot-laying route. The loss of the other Eliason meant that loads for the long journey would have to be restricted, and in any case, there would not be enough spare capacity to carry the gravity meter and magnetometer on the dog sledges over the plateau. With severe misgivings, I agreed to leave the instruments behind at Churchill Depot, for collection by the aircraft, once they decided that they could fly. Boxes of geological specimens were also left at the depot. The gravity meter alone cost as much as a three-bedroomed semi-detached house (about £3500 in 1963!), and was not insured.

The trip to Three Slice Nunatak turned out to be one of the best we had had, with superb surfaces and largely sunny weather and the Eliason behaved itself in accordance with the textbook! At one point, we could actually hear the engines of the approaching Otters, but the cloud base was too low, and they had to turn back to Adelaide.

After waiting for a fortnight at Three Slice, in the hope of an airlift, we covered up the Eliason and left it to await recovery by the aircraft, whilst we six men with three dog teams sledged across Trail Inlet, up Bill’s Gulch and so back to base. Apart from a tricky crevasse rescue for the Moomins, it was a relatively uneventful journey and we arrived on 26th January at 4 a.m.

On Sunday 1st March, air travel finally became possible, and Tony accompanied the pilot to Churchill Depot, to recover the precious instruments and specimens. I do not recall if the Eliason was collected from Three Slice Nunatak by a subsequent flight.

Peter Kennett, Geophysicist, Stonington 1963

References –

BAS Reports:

Fleet, M. Depot journey to Three Slice Nunatak, March 25th to May 9th 1963

Fleet, M. et al. East Coast, or Larsen Project, Spring 1963 (including a final Eliason Report)

Kennett, P. Report on the Eliason Motor Toboggans, Stonington Island, 1963

Swithinbank, C. 1962. Motor sledges in the Antarctic. Polar Record Vol 11, No: 72.