(Header Photo: Brian Hill – caringly developed in the best Bluff water supply and nearly bleg-free)

History

Position Lat. 71°19’59″S, Long. 68°16’40″W

Occupied 20 February 1961 to present, intermittently. Occupied during the winters of 1961, 1962, 1969–75. Summer-only occupation since 1975.

Establishing Fossil Bluff – 1961

Using both single-engined Otters (294 and 377), the pilots David English, Ron Lord, and Bob Bond flew more than 13,000 nautical miles, in over 130 flying hours, between February 19th and March 4th, 1961, to move 23 tons of materials, fuel, and supplies, plus people, from Adelaide Island to the remote site of the new Base KG at Fossil Bluff.

It was ready for Brian Taylor, Cliff Pearce, and John Smith to spend the first austral winter there, starting on March 4th, 1961. In 2004, Cliff subsequently published a splendid account of his experiences in his book, ‘the Silent Sound’.

Leaving Stonlngton – Cliff Pearce

Saturday March 4th dawned brilliantly sunny and crisp. The sun on the snowy hills dazzled our eyes, and the nip in the air sharpened our awareness of the environment as we looked appreciatively at the majestic world around us. We moved down to the airstrip, an area of thick ice a few yards away from an ice cliff on the southern side of Neny Island. We sat on our piles of luggage and waited the Otters arrival from the piedmont airstrip at Adelaide Island. A Muskeg came out from the base along the highway, lifting the powdery snow as dust. A group of passengers clambered down to wish us well before they carried on down the road and disappeared round the end of Neny Island, making for the ship. Suddenly we heard the noise of the aircraft humming their way over the ice. They hove into view and made a circuit of the airstrip, passing in front of Roman Four; how small they looked against such a background! The weather was so absolutely perfect that it was hard to realise that this was the Antarctic.

The planes landed, and we loaded our gear before climbing aboard; John and Brian in the first plane, piloted by Ron Lord, and myself in the second, piloted by Bob bond. All was ready and I watched the other Otter take off. Then our conversation became lost under the noise of the engine. The place accelerated down the runway, stumbling over the occasional irregularity. Soon the bumpiness stopped and we felt the smoothness of the still air as the ice fell away beneath us. Out towards the ice edge we sped, glancing down at the little red ship that was the John Biscoe, hugging the ice edge. We turned southwards and gained altitude. The ice below us was sharp-edged and contrasted sharply with the blackness of the waters. Some distance off. a mosaic of ice floes drifted further out to sea. Elsewhere icebergs, recently freed from imprisonment in the fast ice, were beginning their peregrinations northwards.

We flew towards Cape Berteaux, crossing once more the edge of the fast ice which extended north of the Terra Firma Islands, small outcrops of security gratefully named by members of the British Graham Land Expedition, who found themselves on the ice in this area when it was breaking up. We crossed the almost unobtrusive boundary where the snow drifts on the sea ice merged with the ice face of the Wordie Ice Shelf; we looked down on this crevasse-scarred mass of ice, crevasses whose defining edges showed black and gaping from our position high above.

We passed close to Mount Edgell, a rocky nunatak sticking up out of the ice and reaching almost 6,000 feet above sea level, and as we moved on, the great white highway of King George VI Sound was revealed. Some half an hour later, the immensity of our new environment was obscured by a veil of stratus cloud, until we suddenly emerged over Succession Cliffs. Bob pointed to the wooden hut, a minute speck at the foot of the scree at Fossil Bluff. After one hour and fifty minutes we landed, followed a few minutes later by the second Otter, which had flown by a slightly different route. We entered our new home and made a hasty cup of tea for the four airmen. Soon Ron and Tom, and Bob and Roy climbed back into the planes. The engines spluttered to life, the planes moved over the ice and lifted. We watched as they became diminishing specks to the northern horizon and the hum of their engines faded away into the silence of the Sound. The sun shone over Graham Land, nothing stirred; we were truly on our own……

So we three went inside the hut, sat down and considered.

| Pearce, C.J. (Cliff) | Meteorologist |

| Smith, J.P. (John) | Meteorologist |

| Taylor, B.J. (Brian) | Geologist |

The First Wintering Party – Settling In

It was very quiet in the hut on March 4th after the planes flew off. Outside there were piles of completely unsorted equipment and supplies, all jumbled together on the scree slopes below the hut: boxes of ordinary food and boxes of sledging food, other boxes of nutrican (for the dogs when they came), drums of fuel for the aircraft, sacks of anthracite, lengths of timber and plywood panels, rolls of linoleum, shovels, and sledges. A few yards away were the two tents, still up, which the building party had used for ten days. On a rocky platform adjacent to the hut was a Fetter generator, securely sited by Mike Tween but lacking any covering building, and with no wires leading from it!

We intuitively established our priorities:

- Firstly we had to build a generator shed and connect up the generator and install lights; the power was also needed for our radio.

- Secondly we had to sort out the parts of the Rayburn stove assemble and fix them, and test them for our heating and cooking.

- Thirdly we had to take in and sort out the food.

- Fourthly we had to decide how to use the space within the hut.

In between these major priorities there were other important tasks; Brian naturally wanted to get a look at the slopes before they became snowed over, in order to plan his geological work; I wanted to establish a meteorological station; and there were interior furnishings, cupboards and work benches, for example, to erect. That first evening we sorted out our own personal gear, and over a first cup of tea together we studied our hut.

From Stonington to Fossil Bluff – Dog Teams and Muskegs

(Transcribed from Cliff Pearce’s book “the Silent Sound”)

The prime objective of establishing Fossil Bluff as a forward base was that it should make possible geological and survey work on Alexander Island and eventually in areas further afield. It was therefore of paramount importance that men and materials and equipment should get to Fossil Bluff as early as possible, preferably during September or October, when at least three or four months of field work could be carried out.

John Cunningham, Base Leader, was an outstanding mountaineer who had climbed extensively in the Himalayas and elsewhere. He was serving the second of three consecutive years down south, all as base leader, the first at Port Lockroy, the latter two at Stonington Island. (Later still, in 1964 he returned to Adelaide Island and led the first ascent of Mount Andrew Jackson, the highest mountain in Graham Land at over 11,700 feet.)

Mike Tween and Tony Quinn spent almost the entire year at the base, apart from short local trips, in order to provide power and to maintain radio communications with other bases and with the various

In December, 1961, Pilot Warren Lincoln joined Bob Bond and Ron Lord in the similarly demanding task of restocking the base and supporting its field workers, (some of whom had sledged there over the sea-ice; others had been flown there). He is shown standing proudly alongside 377, on Deception Island, at the start of the 1961-62 season.

1962

Wednesday 14th February – Peter Kennett

At last I was able to get a flight to Fossil Bluff with the gravity meter (c.270 miles away). They have been making flights all the week, taking various necessary personnel back and forth, so this was the first occasion when I could go.

I went as co-pilot to Bob Bond flying Otter “Blue Label” (294) with 1600 lbs. of coal and paraffin as cargo. We lumbered into the air at about 8.45, flew over the ship and then headed for the Sound, climbing all the while until we reached about 6000 feet, where we levelled off. Ron, with Derek Gipps co- piloting, took off after us.

The weather was absolutely perfect, and we could see the mountains on Alexander Land, 200 miles away as we climbed away from Adelaide Island. It was wonderful to be able to sit up there looking down upon the whole of Marguerite Bay, now filled with loose ice and to see all the familiar mountains and headlands of Grahamland, made famous by the B.G.L.E. and Kevin Walton and the boys of the early days of FIDS. As we went along we could make out, quite clearly, Millerand and Neny Islands, Red Rock Ridge and the other landmarks around the base and then, further south, the Terra Firma islands and then at the entrance to the Sound, Cape Jeremy itself. Although this is at about the same latitude as the north end of Alexander Land, the shelf ice does not start until twenty miles or so further south, the gap being filled by thick fast ice, now with a few cracks running across it.

For mile after mile we flew on over the shelf ice close to the bluffs and headlands of Alexander Land, which, but for the preponderance of ice, could easily have been in the “Badlands” of the Wild West! Just before we reached the Bluff we flew low over Tal and Rod setting out on their rugged geological man-haul trip.

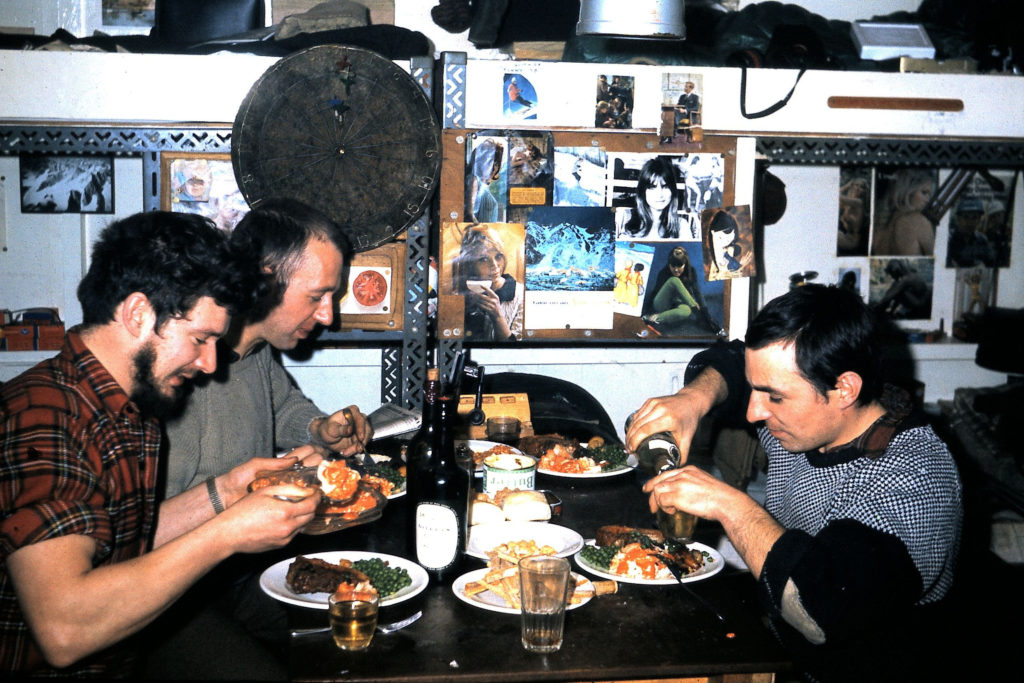

We touched down shortly before 12, to be met by Sam (Blake) and Brian Bowler who are now the sole occupants. Offloading only took a few minutes, so we went into the hut for a cup of tea. It is really quite a pleasant place, being of prefabricated design and a little larger than the hut at base T. It consists basically of one room, with four bunks at one end and a semi-partitioned off kitchen at the other and apart from the sparseness of the furniture e.g. packing cases for chairs! it looked quite comfortable.

After our cuppa, we piled back into the aircraft and headed for T settling down to enjoy, once more, the really magnificent scenery.

We had no sooner touched down at T than the aircraft were refuelled and loaded ready for another trip, which commenced as soon as the pilots had had their sandwiches and coffee. Meanwhile, I went down to the base and started work on the building again.

1962

OIC: Jim Shirtcliffe

| Blake, S.C.B. (Sam) | Radio Operator |

| Shirtcliffe, L.J. (Jim) | OIC, GA |

| Taylor, B.J. (Brian) | Geologist |

| Walker, R.J. (Rod) | Meteorologist |

1968

OIC: Rod Ledingham

| Ayers, J.R. (John) | Pilot |

| Bramwell, M.J. (Martyn) | Meteorologist |

| Ledingham, R.B. (Rod) | OIC, Meteorologist |

| Smith, C.G. (Graham) | Geologist |

| Walsh, J.C. (John) | Air Fitter |

Center: John Ayres (Pilot); Front; Graham Smith (Geologist).

(Photo: Rod Ledingham)

The unexpected 1968 wintering complement of Fossil Bluff following the demise of the Pilatus Porter on the Plateau – henceforth know as Porter Depot.

The five men, none of whom expected to winter at Fossil Bluff, were cramped into a 4-bunk hut, and at the end of the winter, when expecting to be relieved by the new Twin Otter aircraft from Adelaide, were further delayed when the aircraft went “lost” on the East Coast of the Peninsula.

Read the complete story:

The Players at the Bluff – Graham Smith

After the failure of the Pilatus Porter on take off at the end of February 1968 Rod Ledingham (met), John Ayers (pilot) and myself had the option of sledging to Stonington or Fossil Bluff, or attempting to reach the seaward edge of the Wordie Ice Shelf to be uplifted by the John Biscoe. In the event, although John Ayers was anxious to return to the UK and obviously didn’t relish the prospect of another winter, we decided to make for Fossil Bluff. This was largely because I was familiar in part with the route, but also because Martyn Bramwell (met) and John Walsh (air mechanic), in their first season, had been marooned at Fossil Bluff by the demise of the aircraft. We had one team, the Players, but two sledges so for safety sake we split the dogs.

All went well for the first five days but then, with 45 miles to go, in white-out conditions, the dogs suddenly stopped and refused to move on. We could not see anything wrong, the surface was a bit icy but that was all. Anyway, we made camp and hoped the dogs would be in a better mood when the weather cleared. I eventually did clear – to reveal that we had been heading for a large crevasse, followed by a horrible icefall. I honestly feel that if it had not been for the sixth sense shown by Rod Ledingham’s lead dog, we would have been “up the creek” in no uncertain manner.

Further Medical Consultations by Radio – Graham Smith

Three survivors from the Pilatus aircraft had to overwinter at Fossil Bluff with orders to return to Adelaide as soon as the sea ice conditions made travel possible. One of the three, Martin Bramwell was prone to a form of excema that he had kept under control at base and this was not improved by the rather cramped conditions of five men living in a four man hut.

Small bases had limited medical facilities and he needed medication so he contacted the Doctor at Adelaide by radio. He was told to use a certain medication which had proved singularly ineffective when he had used it six months earlier but there was none available in the Bluffs medical kit.

In desperation the doctor suggested that he should look in the medical box for use with dogs to see what he could find. He found an ointment, he tried it.

1969

| Bell, C.M. (Mike) | Geologist |

| Elliott, M.H. (Mike) | Geologist |

| Kistruck, G.W.F. (George) | Glaciologist |

| Wager, A.C. (Andy) | OIC, Glaciologist |

20th February – Bill Taylor

Immediate impressions of my first flight from Base T to the Bluff. “As the weather slowly improved during the afternoon of 20th February, I was getting excited. We loaded the Twin-Otter (radio call sign Alpha Oscar) and after smoko, Mike Fielding (Stonington Surveyor) and I climbed aboard with squadron Leader Derek Smith as pilot”.

Knowing what had happened to Bluff- flight personnel during the previous year (including an unplanned winter and an unplanned landing on the Larsen Ice Shelf) I made sure that in addition to my personal emergency kit and basic requirements for a couple of weeks of a planned stay, I actually took enough in case I was forced to winter.

Taking off at Adelaide was always the cause of an adrenalin rush. Read on…

The Pyramid (Bill Taylor)

It was sometimes the case that while summer flying conditions at Fossil Bluff might be excellent, the weather and flying conditions at Base T might be poor, thereby providing an opportunity for the Bluff residents to snatch the chance for some local R and R. The most obvious activity for those with the inclination was an ascent of Pyramid, the Alexander Island peak that sits directly behind the hut, and is literally a huge layer-cake of horizontally-bedded fossils that give the Bluff its name.

In late February 1969, the Bluff residents were me (metman); Mike Elliott (geologist) and Mike Fielding – Stonington surveyor who was at the Bluff to get a star-fix for the topographical survey.

On 26th February, while we kept our good flying conditions, they began to deteriorate at Adelaide and therefore our Bluff team only had to handle one flight in from each of the aircraft. This gave us a quiet day compared to the frantic aircraft turn-arounds that were the norm in good weather, so when our painting of the Maudheim-mounted caboose roof was completed by early afternoon, Mike Fielding and I saw this as a unique opportunity to climb The Pyramid.

A letter written to my parents reads:

“The view from the top was well worth the effort… On scrambling up the screes it is easy to see why this place is called Fossil Bluff, for the rocks are creeping with fossilised plants and small animals.”

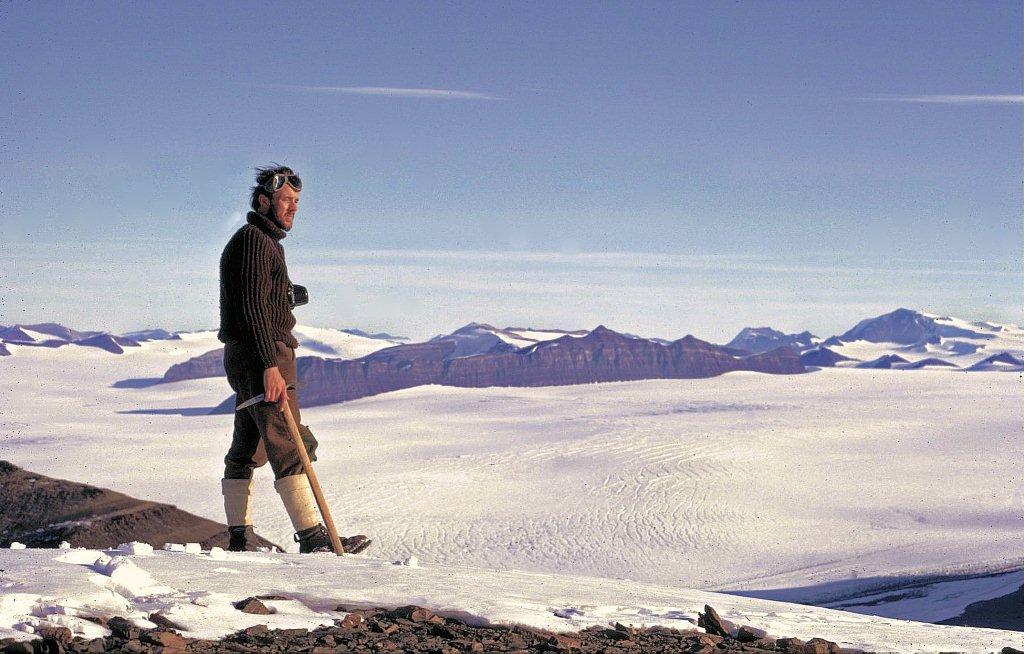

But pictures often speak louder than words:

March 3rd

On the 1400 radio sched, the news was that Single Otter (VP-FOM) had just smashed its under-carriage while landing on the Grahamland Plateau, when putting in a depot in the Amphitheatre about 25 miles south of Stonington. The plane was beyond repair but there were no casualties among the 5 on board, (one of them being John Walsh) and they had been spared a difficult walk to Stonington having been picked up by the Twin. The sched had concluded by telling us that the whole programme focusing on Fossil Bluff was back in the melting pot.”

Seven Happy Years – Mike Bell (written October 2009)

I worked as a geologist on the Antarctic Peninsula, Alexander Island and South Georgia during seven years between 1968 and 1975. My mother died recently, and carefully filed amongst her papers I found some of the letters I had sent 40 years ago. Here are a few unedited snippets from those letters together with some reminiscences to try to paint a simple picture of our fun and adventure during those happy years.

“Gremlins in the South” – Autumn 1969 – George Kistruck

All Photos by George Kistruck

“Gremlin – a term denoting a mischievous creature that sabotages aircraft. It originated in RAF slang in the 1920s among British pilots stationed in Malta, the Middle East and India. Gremlins were believed to wreck engines, and drink petrol, besides many other unhelpful activities.“

How did I end up at Fossil Bluff? Well, Sir Vivian Fuchs himself arrived one day when I was at university, to give a “milk-round” recruiting lecture for BAS. I found myself thinking “Hey, I could do that. I would like that! Good fun! The sort of things that I like to do”. But apart from the film he showed I don’t remember much at all about what else was said on that occasion. It was several years later that I applied to join.

1970

| Gurling, P.W. (Paul) | Surveyor | |

| Hill, B.T. (Brian) | GA | |

| Kistruck, G.W.F. (George) | OIC, Glaciologist | |

| Macrae, M.D. (Malky) | Tractor Mechanic |

November 8th

First Ascent – Mt Bagshawe – Batterbee Mountains – Brian Hill

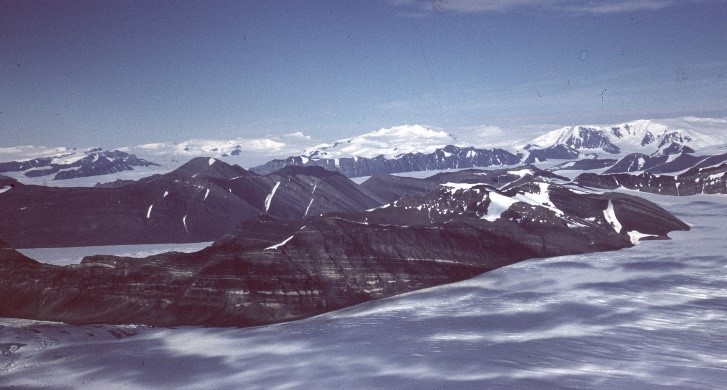

November 8th. The Batterbee Mountains dominate the landscape as seen from Fossil Bluff on the opposite side of George VI Sound. Named by the BGLE of 1936 Mount Bagshawe at 2,200 m (7,200 ft) tops the group.

The Batterby Mountains dominate the landscape as seen from Fossil Bluff on the opposite side of George VI Sound. Named by the BGLE of 1936 Mount Bagshawe at 2,200 m (7,200 ft) tops the group and is indeed the highest mountain for almost a hundred miles around.

Our wintering group at the Bluff comprised of George Kistruck (glaciologist & OIC), Paul Gurling

Below is a selection of photos supplied by Brian Hill. More writings to follow, but hopefully in the interim they will arouse memories, tales and anecdotes from the winterers…..

1971

| O’Donovan, R.J. | GA |

| Pearson, M.R. (Martin) | Glaciologist |

| Rose, I.H. (Ian) | Glaciologist |

| Walker, R.S. | OIC, Tractor Mechanic |

1972

| Pearson, M.R. (Martin) | OIC, Glaciologist |

| Rose, I.H. (Ian) | Glaciologist |

| Wager, A.C. (Andy) | Glaciologist |

| Whitworth, G. | GA |

A Tale of Rasmus – Roger Wilkins

Those of us who remember Marguerite Bay some 50 years ago may be classified by the younger FIDS as a bunch of Old Farts, reminiscing about a mythical, bygone, Golden Age, when men and dogs faced the Rugged South with some 2000km between us and the Edge of Civilization (aka Stanley). There is at least a little truth to this – remember Steve Vallance’s recounting of the evacuation of Rocky Hudson – but what you are about to read is not a tale of the normal kind, for this is a tale of a husky Old Fart, a Tale of Rasmus.

Those who remember him may also remember that, in a moment of compassion, to spare Rasmus from the lead tablet that would have dispatched him to the Great Span in the Sky, given his age and inability to continue as a useful work dog, Bert Conchie smuggled him onto his plane and flew him down to Fossil Bluff, for a peaceful retirement amongst the glaciologists.

1973

| Bishop, J.F. (Jim) | Surveyor, Glaciologist |

| Hobbs, S.A. (Simon) | GA |

| Jamieson, A.W. (Andy) | Glaciologist |

| Tindley, R.C. (Rog) | GA |

On Thin Ice – Roger Tindley

During the Midwinter 1973 Falkland Islands Broadcasting Service record request programme, the Stonington Fids requested “Your Baby Has Gone Down the Plughole” for the Bluffers. This is the story of how such a request came to be made…

At Fossil Bluff we regularly used Muskeg tractors. They were used to establish large ice movement schemes, to re-supply our field station at Spartan Cwm, and to lay depots for dog teams and our own operations.

The Muskeg tractor was made by Bombardier Canada in the early ‘60’s. Intended for oil exploration in the north-west of Canada, it also served in mining and forestry. The Muskeg could be found all over the world, and there remain many working machines (including one at Fossil Bluff).

1974

| Bishop, J.F. (Jim) | Glaciologist |

| Tindley, R.C. (Roger) | GA |

| Tourney, F.G. (Graham) | Glaciologist |

| Walton, J.L.W. (Jon) | Glaciologist |

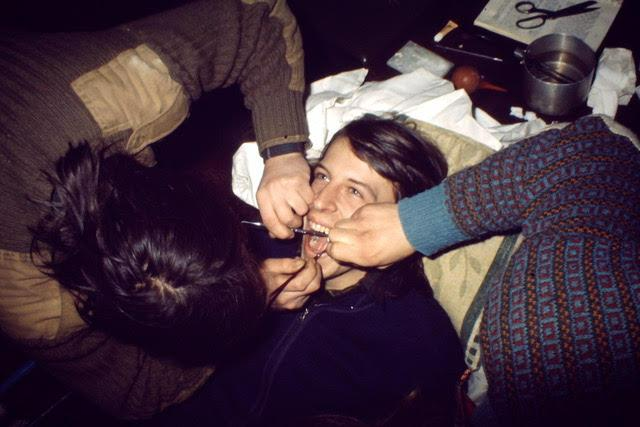

The Extraction of RogT’s Tooth

Winter at Fossil Bluff lasts about 2 1/2 months. We defined the Winter, generally, as the period of darkness, when the sun never crept above the horizon, and to the extent that the light is too low to take scientific or surveying observations.

Towards the end of Winter, in August 1974, we were preparing for our first early Spring trip. However, RogT (Roger Tindley) had been experiencing increasing pain each day from his upper left molar tooth. We were concerned that this would impact our Spring travel season. This travel period has limited days for field work between the return of the sun and the George VI Sound’s (the “Sound”) surface becoming waterlogged. The sun soon heats up the dark mudstone formations of East Alexander Island and copious melt run- off forms fast flowing streams which then culminate in large, blue lakes on the ice shelf surface. Surface travel (and field work) then becomes impossible. So, we have to get all our work done before this occurs. Each day of early spring, therefore, is important.

The Old – The Last Great Dog Journey from Stonington – Chris Edwards

The story really begins at Stonington at the start of the 1974-5 season with the departure of 8 sledges on the 29th August 1974 of the field parties of surveyors, geologists and geophysicists. It also marked the beginning of the end for Base E and also for dog sledging in Antarctica. My diary entry for the 28th reads “…:lunch then Doom! Had to put down 8 dogs – Rona, Nog, Zonda, Dianne, Belle, Rocky, Gareth and Castro.

However, things went smoothly and the whole nasty affair was over by smoko….. Not a good day – feeling very sad”.Many of these dogs I had had in my team and, as the doggy man, knew them all intimately. They were “surplus to requirements” in the overall scheme and it was a shameful, brutal thing to have to do.

At 0940 on the 29th, after a last poignant look around, I made my way to the dog spans and, with the other seven teams departing ahead of me, left Stonington, my home for the previous two years, for ever.

The New – A Historic Meeting – Jonathan Walton

In the 1960’s, small motorised vehicle were appearing on the various bases in Marguerite Bay. Scorned by most of the husky brigade at Stonington for (quite rightly) not being reliable enough for the unsupported long distance travelling that constituted most of the field work at that time.

That is not relevant to this tale – thankfully travelling up and down GeorgeVI ice shelf is very straightforward and pretty safe so single skidoo units were not uncommon.

However, Fossil Bluff, that tiny outpost of humanity away from the coast on George VI Ice Shelf did not have dogs – they relied on the 3 Muskeg tractors (named Blodwen, Aphrodite and Fred – don’t ask me why, I didn’t name them!!) and one or two rather clanky and unpredictable FoxTrac motor toboggans. Between these vehicles quite a bit of glaciological work was achieved on and around the ice shelf. By the early 1970’s the Fox Trac had been replaced by 399cc “Alpine” skidoos and later by some “Valmont” 440c skidoos. By the time I arrived in 1973, the 4 of us (Jim Bishop, Rog Tindley, Graham Tourney and your scribe Jonathan Walton) had in our fleet a total of 5 skidoos and 3 Muskeg tractors.

Our Mechanic for the 1974 winter was Roger Tindley who, with the help of a newly built and comparatively spacious and warm garage had got all 3 muskegs running (2 of them with major rebuilds) and the skidoos serviced regularly and becoming ever more reliable. Indeed, in March/April May 1974 the 4 of us had completed an unsupported trip of around 400miles to the seaward side of the Bach Ice shelf on the West Coast of Alexander Island – the first time that skidoos had been used within BAS for a journey like this. That trip is described elsewhere but we had proved that linked skidoos could operate relatively safely in difficult terrain. We finally got back to Fossil Bluff on 24th May, well after the sun had left for the winter, having had a week of temperatures around -45C.

1975

| Lennon, P.W. | Glaciologist |

| Stewart, T.J. (Tim) | Tractor Mechanic |

| Tourney, F.G. (Graham) | Glaciologist |

| Walton, J.L.W. (Jon) | Glaciologist |

The Last Winter at Fossil Bluff

The story of our return to the Fossil Bluff base from fieldwork in June 1975.

Bad light had precluded further accurate surveying and glaciological work. The sun had disappeared below the northern horizon and would not return, at our location, for two and a half months.

Winter Work at Horse Point – Our Most Challenging Project

The story of the Horse Point Project during the last winter at Fossil Bluff, by Graham Tourney