parties that were in the field. This was especially important when things started to go wrong. I had shared a year with Mike, and Roger Matthews, one of the meteorologists, at Deception Island in 1960, so we all knew each other very well.

Brian Wigglesworth had trained in meteorology in Stanmore, with others of us, and had taken on the role of forecaster for the aircraft when he was at the Argentine Islands during 1960.

Arthur Fraser was one of two geologists; Brian Taylor, the other, was already at Fossil Bluff. We three had shared a cabin on the long journey south in the Kista Dan in 1960. Arthur was based at Wordie House, Argentine Islands, during 1960 after the failure to relieve Stonington earlier in that year; Brian had returned home after the debacle, and was now back for the first of two years at work on Alexander Island.

Bryan Bowler, on secondment from the army, was responsible for the Muskegs.

Bill Tracy had major responsibilities for the dogs. He had worked at Hope Bay during 1960, so had plenty of appropriate experience.

Dr Brian Sparke had worked at the Argentine Islands during 1960.

Howard Chapman and Bob Metcalfe were the two surveyors, who had major commitments to surveying work when Fossil Bluff was finally reached.

During July the dog drivers started training the dog teams, and the Muskegs were prepared for the great journey south. Thirty dogs had been landed in February and there were already twelve dogs who had sledged down from Horseshoe Island in the previous August so there were sufficient for at least four teams if necessary. Several of the men were trained to drive the two Muskegs under instruction from Bryan Bowler.

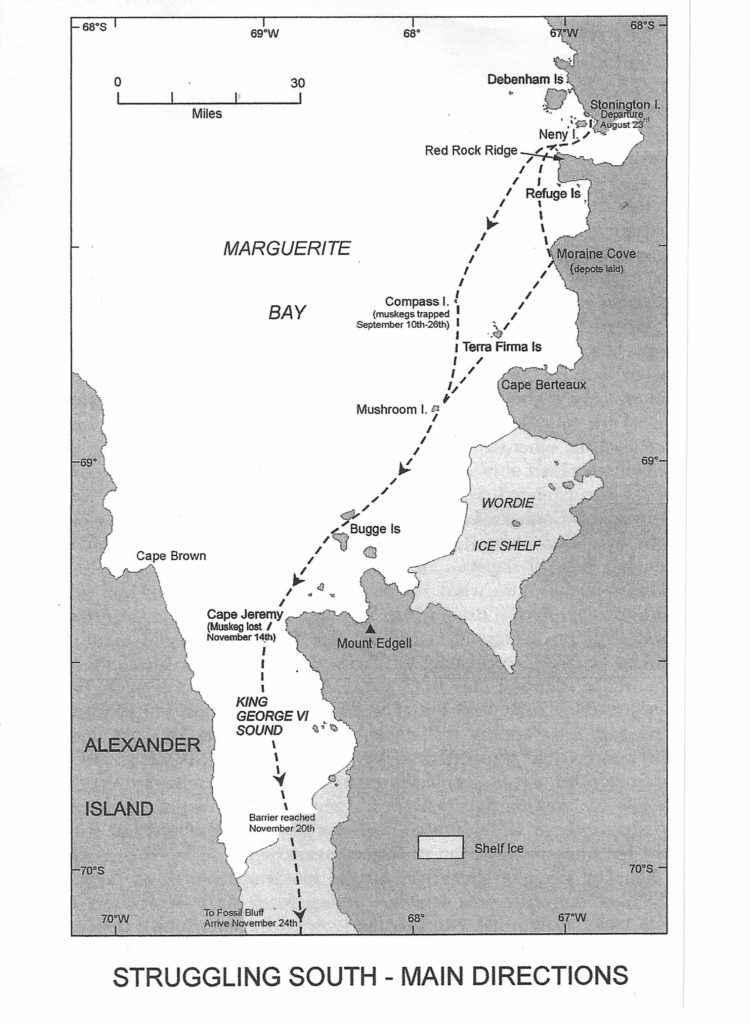

At Fossil Bluff we listened on the radio for any signs of movement, and by August 15th we were talking optimistically; of lengthening days and of being outside and the arrival of the men from ‘Stonners’. By the 17th we had confirmation that they would be starting in the following week and, sure enough, on the 23rd two dog teams, the ‘Players’ and the ‘Spartans’ with Bill Tracy and Brian Wigglesworth driving together with Roger Matthews, set out on what was to have been an initial depot laying journey. Four days later they reached Compass Islet about forty miles from Stonington. We felt delighted that movements were taking place so early! On the 24th the two Muskegs started out with Bryan Bowler, Howard Chapman, Arthur Fraser and Bob Metcalfe. They were towing four well laden sledges, again in order to lay a depot on Mushroom Island, about fifty miles to the south. My diary recorded optimistically:

August 24th. The sledges and Muskegs have started from Stonington and are on their way. Soon our quietness and peace will be shattered, but it promises to be an interesting summer.

During a reconnaissance journey in July it had been observed that the ice closest to the coast was full of consolidated lumps of brash ice and bergy bits which made it unsuitable for the Muskegs. They therefore moved out to the west and, after ten days, including a stop on Compass Islet, they succeeded in reaching Mushroom Island towing two of the four sledges. The next day they returned to Compass Islet to collect the other two sledges. They now laid their depot of supplies of fuel on Mushroom Island. On September 8th they set out .northwards for Stonington Island to collect more supplies. As they approached Compass Islet again, a gale blew up and blizzard conditions over many hours caused the ice to break up where they were camping, just off the islet. At Fossil Bluff we heard of their predicament over the radio when we picked up a ‘Mayday. Mayday’ call sent out by Bryan Bowler on September 10th. The party found themselves on a large detached ice floe floating amidst a mass of broken ice. Very fortunately for them, the ice floe had been pressed against the islet and they were able to scramble ashore over the few yards where the ice and the shore touched. They had six weeks of food and fuel supplies with them, based on half rations per man.

There was a real prospect that they might lose both Muskegs if the ice floe drifted out to sea; in the event, the Muskegs remained on the ice floe for a week. Eventually, with good fortune, they were able to get them ashore to the foot of an ice cliff where they were at least safe, but unusable until the ice formed again.

The dog sledging teams had arrived at Compass Islet on August 27th, but they had been unable to move for a week due mainly to thick cloud at sea level. However, as soon as the opportunity arose on September 3rd, they moved quickly southwards and reached Mushroom Island where once more the weather closed in and they remained there for a week. Another break, however, enabled them to make progress and on the11th, they reached the Bugge Islands, fifteen miles north of Cape Jeremy.

That same day, John Cunningham at Stonington Island reported eighty-knot winds which had broken the ice and produced leads everywhere, and the outlook became both dangerous and disappointing, for there was no prospect of the Muskegs getting back to Stonington for the rest of their cargoes. At this time, therefore, the Muskegs were marooned on Compass Islet, and the dog teams were well to the south of them. John Cunningham tried to be optimistic, but the outlook in the near future was definitely bleak. Two movements were then set in train:

– The dog sledgers were to attempt to go back from the Bugge Islands to Mushroom, then on to Terra Firma Island to lay a deport; they completed this in five days and went on to reach Compass Islet with some food boxes to supplement the supplies of the marooned

men;

– John Cunningham and Brian Sparke were to sledge from Stonington Island to the Refuge Islands, climb to the highest point and study the ice, but they were held up for five days by bad weather. They eventually reached their destination after almost a week.

The Governor of the Falkland Islands, Sir Edwin Arrowsmith, then intervened. On September 14th he issued a statement requesting that the men be withdrawn from Compass Islet as soon as possible, leaving the Muskegs to be picked up by the John Biscoe when the summer came. A week later a telegram went to John Cunningham from the SecFids in Port Stanley declaring that the summer programme was OFF. The Muskeg party was to withdraw to the Terra Firma Islands and leave the Muskegs there. The field men were to be deployed back at Stonington Island to do what work they could in that area! At Fossil Bluff, our spirits sank; we wondered, however, whether the dog teams might continue on their way to us as the dogs were naturally able to overcome difficult ice conditions more easily than the Muskegs; we even wondered whether the aircraft might fly down to Fossil Bluff and evacuate us.

Back at Stonington Island, at the centre of conflicting orders and aspirations, John Cunningham was working on a variety of strategies to keep the summer programme alive. He tried to get the two Otters to come down to help. Although they were sorely needed, the aircraft apparently could not be sent down south. On the 25th more new plans emanated from Stanley, and some decisions were made. The two Muskegs were going to make a further attempt to reach Fossil Bluff, but Arthur Fraser was going to return to Stonington Island and work on the Blackwall mountains some five to ten miles from the base, with John Cunningham and Brian Sparke in support. The two dog teams would also try to reach Fossil Bluff, though Roger Matthews would return to Stonington Island to provide weather information. The men actually in the thick of the difficulties were despondent, for it was felt that the plans were being made far away by men not really au-fait with the situation – the Muskeg drivers were now being told to get their vehicles to Fossil Bluff at all costs, whilst on the other hand, John Cunningham and Brian Sparke were being told not to try to go to Compass Islet because the ice was too dangerous! John and Brian therefore pushed further south to leave a depot at Moraine Cove by the Bertrand ice piedmont, which they reached on October 4th. When John and Brian finally headed north five days later, they travelled on mushy ice only four inches thick, through which John fell.

In the complicated pattern of journeys which then ensued the following deployments were made:

– Bill Tracy and Brian Wigglesworth with their dog teams travelled the thirty miles to Moraine Cove to pick up the material from the depot and then took their supplies back to Mushroom Island.

– John Cunningham and Brian Sparke made another run with further supplies from Stonington to Moraine Cove, where they waited for a day or two for Bill Tracy and his colleagues to return in order to pick up these additional supplies (including mail), to take south. Bill had to stay there for a few days because of snow blindness; meanwhile Roger Matthews returned to Stonington with John and Brian.

It was to be over six frustrating weeks before the sea ice around Compass Islet had frozen sufficiently for the Muskegs to try to move south again on October 24th. At last they were able to make their way to the Wordie Ice Shelf where they eventually linked up with Bill Tracy and Brian Wigglesworth on October 25th.

By the end of October, therefore, matters were becoming clearer – the two Muskegs with three men and four heavy sledges (having had the Moraine Cove depots transferred to them), and the two dog teams with two men, were on their way to Fossil BIuff. and were approaching Cape Jeremy. The rest of the men had returned to Stonington Island, It seemed fairly straightforward for the rest of the journey. By November 2nd the party reached Cape Jeremy and turned south. Progress was slowed as a result of bad weather and it took twelve days to get to a point forty miles from the ice barrier marking the northern end of King George VI Sound. Nevertheless, things were going well and success was at hand when disaster struck on November 10th. The Muskegs were being driven in an area where leads had frozen and had been covered by snow.

Several such areas had been negotiated before, when suddenly the leading Muskeg sank into deep snow and water started trickling into the cab through two small holes in the cab floor. It kept sinking. Bryan Bowler jumped out and cut the sledge free from the Muskeg as it disappeared into the depths below; it took two minutes to do so and took with it both Bob Metcalfe’s cameras and Howard Chapman’s skis. Howard, who was driving the second Muskeg thirty yards behind later remembered the bubbling of the exhaust as it sank into its watery grave with the engine still running, and the tail end of the cut tow rope as it ran across the ice and followed the Muskeg into the depths. They spent a lot of time looking despairingly at the great hole!

Bill Tracy and Brian Wigglesworth, who had moved on well ahead of the others, immediately turned back north to help – an eight day journey. The five of them reorganised the loads, the surviving Muskeg pulling three of the cargo sledges. A few days later, on the 20th. The party finally reached the barrier. where a huge rift in the shelf ice presented difficulties for them to get around. They only travelled two miles during the next day but achieved their objective, and had climbed nearly 150 feet on to the barrier surface. The road ahead was straight and clear!

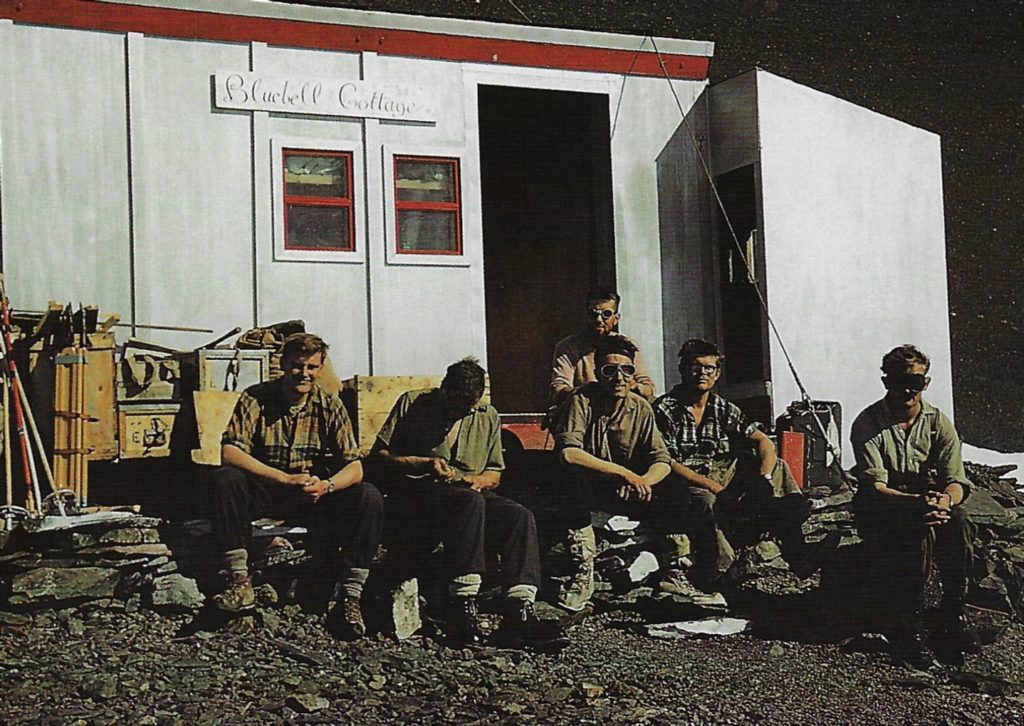

By the 22nd, we heard at Fossil Bluff that the party was only thirty-four miles front of us, so John and I climbed the slopes above the hut and cleared snow so as to mark the words WELCOME in large letters. We tidied up the front of the base hut and painted the name ‘Bluebell Cottage’ above the door, we also went down into the Sound and planted a notice, ‘Cottage Teas 1.4 miles’. Travelling on the ice of the Sound we knew to be easy, so we were not surprised when the last thirty-four miles were covered in a few hours. Thus it was that at 1.00 pm on November 24th they arrived, having travelled approximately 350 miles in all, although the actual distance from Stonington Island to Fossil Bluff was closer to 240 miles. It had taken them ninety three days, although on seventy-three of these no travel was possible for the Muskeg teams. Amazingly, however, they had covered 100 miles in the last three days. The men. Bill Tracy, Brian Wigglesworth, Bryan Bowler, Howard Chapman and Bob Metcalfe all looked bronzed and fit; the dogs were very tired. During their journey they had no opportunity to have a bath or shower (neither would they enjoy such luxuries now that they had arrived!); they had also spent a great number of days lying up in their tents when it was impossible to move. It was sad to see just one of the two Muskegs which we had unloaded onto the ice from the John Biscoe on March 1st, finally making it to Fossil Bluff.

We were naturally thrilled to see them all, the first new faces since March 4th, a total of 263 days. We prepared the very best meal we could, and sat and chatted for many hours, mainly about the journey, and about plans for future work in the short time ahead.

The outcome of the trip was a matter which concerned us all. Only half of the new supplies had been successfully delivered because the Muskegs had been unable to return to Stonington for their second loads; only one Muskeg had reached the base because the second one had sunk; two dog teams had arrived when it might have been three; five men had arrived when it might have been nine. Perhaps the most damaging problem was the lateness in the season, for by the end of December it was certain that the increased temperatures would make the surfaces for dog travelling very difficult, so that any work had to be completed before then in just over five weeks instead of the anticipated thirteen or fourteen.

Obviously the main cause of the problem was the unreliability of the sea ice. The Muskegs appeared to be unsuitable for long journeys over variable sea ice; they were too heavy and once they were in difficulties they were helpless, though in the following year two new Muskegs did successfully make the journey. The dogs, of course, were able to travel on much thinner ice and had the ability to get themselves out of difficult situations; on the other hand their carrying capacity was very low in terms of helping to resupply a base. There was disappointment in the group that the two Otters were not flown down from Deception Island to Adelaide Island and then to the sea ice at Stonington. John Cunningham was informed that there were problems with an oil leak, and that they were needed at Hope Bay. Although the aircraft could not have taken the Muskegs, they might have lifted most of the dogs and general supplies, thus giving the Muskegs an easy run, and getting the whole summer programme off to an early start. (The Muskegs had actually reached Mushroom Island on September 2nd, it was only when they returned north for their second loads that they became trapped on Compass Islet.)

Perhaps also the lines of command were confused. John Cunningham was the leader in the field and he knew better than anyone what needed to be done. However, he had to defer to John Green, SecFids, in Stanley, who was probably getting advice and instruction from Sir Vivian Fuchs in London. Then suddenly, the Governor of the Falkland Islands, Sir Edwin Arrowsmith issued his request/order for the men to be withdrawn immediately from Compass Islet. Eventually, dog teams and men, and ultimately the Muskegs, seemed to be criss-crossing Marguerite Bay in all directions. Many of us now gathered at Fossil Bluff had been on the Kista Dan in the 1960 season and on the John Biscoe early in 1961. Now, as we reviewed the recent journey, and its limited degree of success, we began to wonder whether the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey was more than acceptably accident prone!

Cliff Pearce, Met. Deception 1960, Met. Fossil Bluff 1961