Header Photo: (Sunfix observation (for position) on the Bach Iceshelf, 1970, with Paul Gurling) – George Kistruck

“Gremlins in the South” – Autumn 1969 – George Kistruck

All Photos by George Kistruck

“Gremlin – a term denoting a mischievous creature that sabotages aircraft. It originated in RAF slang in the 1920s among British pilots stationed in Malta, the Middle East and India. Gremlins were believed to wreck engines, and drink petrol, besides many other unhelpful activities.“

How did I end up at Fossil Bluff? Well, Sir Vivian Fuchs himself arrived one day when I was at university, to give a “milk-round” recruiting lecture for BAS. I found myself thinking “Hey, I could do that. I would like that! Good fun! The sort of things that I like to do”. But apart from the film he showed I don’t remember much at all about what else was said on that occasion. It was several years later that I applied to join.

Continuing from “Why I” Page and Fossil Bluff page…..

Learning the Trade

I had assumed that I would be put on to map making, which is where most civil engineers who went South ended up. I was surprised to be told by Bill Soman “with your background you could be a Glaciologist”. I managed (just!) not to blurt out ‘Oh? What’s a Glaciologist then?’ I went to Cambridge for a second interview with Charles Swithinbank and Paul Robin. They had known each other very well on an international Antarctic expedition of the early 1950’s, and they knew very well what life on a remote Antarctic outpost base was like. I was surprised by the sorts of thing that they wanted to know: not much about glaciology or surveying, or hard sums; but much more on “practical mechanics” type engineering. They were interested that I used to run old motorbikes, and could manage to keep them going. I had joined an expedition to Spitzbergen at the end of my time at university, which had involved me in lots of fiddly work keeping outboard motors going in bad conditions, coping with skis on melting glaciers, living on porridge and rehydrated food, things like that. This was interesting to them, and seemed to work for me – and I was offered the job.

I didn’t know anything much about glaciology as a subject, so I had to be trained from scratch.

I was given lots of material to read. It was like being back at University again with a director of studies, tutorials, and so on. I had the run of the library at the Scott Polar Research Institute – and that was terrific! It didn’t always have to be technical things that I read. There were hundreds of other books about exploration, about Nansen, and arctic Canada, and so on – and I was getting paid for it! I was sent on a course in northern Sweden to learn the basic nuts and bolts of glaciology, drilling holes in ice, using dyes and that sort of thing. So I was a reasonably competent apprentice Glaciologist by the time I eventually sailed from Southampton on the six week voyage to the BAS bases. The first of these was Halley Bay, to collect glaciology equipment to bring to Marguerite Bay for the new BAS glaciology programme.

Fresh Egg Deprivation

One of the defining memories of my Antarctic experience was when the ship (Perla Dan) came to moor up for the relief of Halley Bay, the first base we reached. It was quite a nice sunny day with picture postcard scenery – blue sky, floating sea ice, and fast ice leading up to the Brunt ice-shelf in the distance about a mile and a half away.

A crowd of Fids was there waiting to welcome us. We moored up, bows on to the fast ice, and threw a rope ladder down. These creatures swarmed up the ladder, over the bulwarks and down on to the deck, and they just charged towards the Fiddery at the stern. I watched in utter amazement. They were filthy! Tattered scarecrows, hair all over the place, beards as ragged as anything! They went straight down to the Fiddery as if they owned it – and loudly demanded fried eggs in huge numbers.

Fortunately the cook had known perfectly well what was going to happen. He’d been asking us for help moving eggs out of the chilled store, so he had great racks of them ready. He got us to bring at least 6 of these trays out of the refrigerator ready to fry up for the visitors when they came. He produced a continuous stream of fried eggs out of the galley; and they ate them all. I thought to myself, ‘Gawd, am I going to be like that in a year’s time?’ But of course I was.

15th March

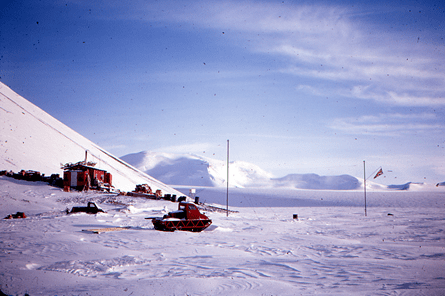

Following the various aeronautical mishaps and poor flying conditions at Adelaide it was mid-March before I finally arrived at Fossil Bluff. Four of us – two glaciologists and two geologists – were to spend the forthcoming Antarctic winter there, conducting various scientific activities in preparation for the main field work with other parties the following summer. Eight weeks previously none of us had even met each other….

There would be no contact with the outside world for six months except by radio exchanges with Adelaide, about 250 miles away, and maybe Stonington occasionally. We were on our own. As we waved goodbye to Derek and the Twin Otter that had brought us in I think we all felt some trepidation at what the future might bring.

Previously the case had been made that four “scientists”, provided they had a reasonable amount of experience, common sense and “nous”, could manage through the winter without specialist mechanical or mountaineering support, or radio operator support either, for that matter. It did turn out to be true, but not straightforward, for us. We were very unlucky with some of the mechanical problems that we had during the autumn. We came through them all right in the end.

So, did we all get on famously together? (A favourite question for most people!)

We did get on, by and large, astonishingly well. Four people cooped up in premises as small as ours were sure to grate on each other’s nerves on occasion. With different interests and backgrounds there were bound to be times when somebody reacted in a way that somebody else really didn’t expect. I am sure Andy felt the burden of command on his shoulders at times. The rest of us knew it, and did what we could (most of the time) to accommodate it. To say we never had differences of opinion would be ridiculous – of course we did. But we were lucky that the way we managed to resolve them was always peaceful. We never had angry words exchanged in high voices, let alone coming to blows.

And what were we supposed to be doing?

In principle, it was very simple: “Field Work”. The two geologists were to travel to Ablation Point, about 50 miles North of our base, and spend roughly 4 weeks during the autumn doing what geologists do: looking at rocks, smashing bits off them for later analysis, finding fossils, measuring and classifying everything… The two glaciologists would be similarly occupied, but with ice instead of rock. Our patch was much more extensive and we were to travel for many miles in various directions setting up the beginnings of a five-year measurement programme. We were to have two Foxtrac motorised toboggans for the purpose, and were to transport the geologists into their area and collect them when they were ready to finish. When the daylight grew too short and the temperatures too low for effective work outdoors we would spend the winter months cosily in our tiny base. There would be plenty to do getting ready for the following spring and summer, when there would be many visiting sledge parties from Adelaide and Stonington.

21st March

Arrangements in the Antarctic seldom work exactly as planned. For a number of reasons many of our supplies for the winter were short of those intended. Instead of two motor toboggans we had only one. Would it be enough to shift four men and their gear 50 miles and back? We hoped so, and packed up the sledge train and set off into the scenery.

Our Foxtrac was a primitive forerunner of the now ubiquitous Skidoo. It was simply a lawnmower engine mounted on a canvas rolling track frame driven through a simple gearbox. Controls were limited to the choice of direction – forward or reverse, and the engine throttle for speed. There was a seat and two short skis at the front for steering. Flat out it could manage only about 5 miles per hour. However it was very sturdy, and on a good surface could pull a string of three loaded sledges – two Nansens and a manhaul – with an astonishing total weight of over 1,800 lbs. We needed all of that. We had the lighter manhaul sledge as a sort of lifeboat in case we might have to walk back to base in an emergency.

Unfortunately by the time we had gone a few miles from base the surface grew much worse. The Foxtrac struggled. We needed to relay our loads, despite the consequences of extra mileage to cover, tripled fuel consumption, and longer journey time. So we did that. Just as it was growing dark, the Foxtrac – quite suddenly – lost all traction power. A link in the drive chain had snapped; the sledges were paralysed. Time to camp, then.

Next day was very windy, not one for travelling even if we had been able. The time was useful: we spent much of it on a do-it-yourself repair for the broken chain, making a new roller and spindle using hacksaw and file from a spare brass rod that we had randomly included with the tool kit. (“It might come in useful”. It did.) When the weather improved, and leaving one of the sledges to be picked up later, we set off to return to base. We could soon see the cause of the trouble: snow powder was being blown on to the cogs of the main track drive, compressing into hard ice and straining the tautness of the chain. We had to take turns crouching on the back of the Foxtrac as it lurched along, playing the flame of a blowlamp on to the offending cogs to prevent the ice build-up. It got us home, but clearly could not be a process used for normal travel conditions.

Score: 1 to the Gremlins: 1 – 0

Something must be done. First of all we had no spare parts for the chain. They should normally have been available, but were among the many items short-supplied in the base relief. So we made several replacement steel pins for a better repair, plus field spares. The first brass effort was nearly worn through already. More importantly, how to prevent the build-up happening? Andy made a metal casing for the drive chain from pieces of sheet metal and angle-iron, bolted to the frame of the machine. We then developed a hot air duct made from used food cans soldered together with the aim of melting off any snow that might still land on the sprocket. Connecting from the engine exhaust to the new chain casing we found that although it did function, the soldered joints were no match for the fierce blast of heat generated by a labouring Foxtrac. The duct collapsed into a sad jumble of scorched baked-bean tins. Back to the drawing board, and instead of soldering, we had to fasten each section together with dozens of tiny nuts and bolts, securely enough to withstand the unavoidable vibration. The result resembled a giant shiny prawn’s leg cranked over the back of the vehicle – but it did hold up for nearly a year.

Score: 1 to us. 1 – 1

It took a lot of time, though. Meanwhile, as a result of the difficulties, we received permission from BAS to use a more “rugged” form of transport to deploy the geologists. Resident on the base was a fleet of three Muskeg Tractors. These very tough tracked vehicles had proved extremely versatile and useful in Antarctica, and one became the favourite of Sir Vivian Fuchs’ Trans Antarctic Expedition. It was the only vehicle which never gave any mechanical trouble during the journey across the continent.

(Sadly, it was abandoned before completing the traverse, for logistical, not mechanical, reasons.) A serious piece of machinery, however, which none of us was “qualified” to drive, let alone maintain the big 4-litre petrol engine and the transmission components. But this was long before the Health and Safety at Work Act reached out its tentacles into the Antarctic. The “Powers that Be” decided that between the four of us we probably had enough experience and know-how to make a successful journey to put the geologists into position.

2nd April

We reckoned it should be straightforward. After a couple of days practising around the base we found the Muskeg very easy to drive. The only obvious drawback was the dipsomaniac fuel consumption, but the extra load, in 45-gallon drums, could be snugly lashed down on to the heavy cargo sledge (technically, a “Maudheim”). But the Gremlins had only opened a ranging salvo so far. The Muskeg, like most vehicles, needed a battery for starting its engine and other tasks. The batteries were the standard 12-volt lead-acid type, and were vulnerable to the intense cold. They must not be allowed to freeze, and were kept indoors on the base until needed for immediate use. If the base was to be left unmanned the acid must be drained from every battery… Well we did know that, of course, and looked after them properly. But on the morning of our planned departure, when we carried two freshly-charged batteries out to the “Keg”, it threw a tantrum and would not start. After hours of chilly diagnosis with voltmeters etc. we decided that one of the batteries was faulty, so we must use different ones. By then it was too late to charge them and fit them in time for departure. End of Day 1.

Score 1 to the Gremlins. 2 – 1

We started the engine next day with some difficulty, and set off towing the heavy cargo sledge and the light manhaul. We made a reasonable distance of about 30 miles towards our destination, and camped for the night – disconnecting the batteries and bringing them into the tents to keep warm. Already the temperature outside was going down below -30˚centigrade. And guess what? Next morning the engine would not start, despite the fact that we had diluted the sump oil with petrol before switching off. (Otherwise the cold might coagulate the oil into jelly.) Eventually, having applied Primus stoves and blowlamps to various parts of the engine’s anatomy, we found the batteries going flat – hardly surprising. A nuisance, but never mind.

Score 3 – 1

Merely a nuisance”, because we had cannily brought with us, for just such an eventuality, a Briggs and Stratton petrol-driven battery charger. No problem? We’d soon get those batteries charged. But no. The charger engine started all right, but the generator produced no output! So we went through all the usual procedures for clearing such a problem, with no success whatsoever. This was a serious blow: we would no longer be able to proceed to Ablation.. We must walk back to Fossil Bluff.

Score 4 – 1

And so, next morning, having “winterised” the Muskeg in case we could not come back to fetch it using the repaired Foxtrac, we set off for home. That manhaul sledge was to earn its passage. I remembered before we even started just how much I had hated manhauling sledges in Spitzbergen – and now this was worse.

8th April

The snow surface was dreadful, with hard windblown sastrugi ridges separated by troughs of deep soft snow. In the low prevailing temperatures (around -25˚ to -30˚C) this resembled a pile of sugar crystals instead of the smooth slippery surfaces of “normal” conditions. It was very hard work. We needed two tents plus our personal kit, food, cookers, etc. Overall the load was such that progress was exhausting and very slow. We weren’t very fit for this degree of physical exertion, and on he first day managed only four hours of slogging to achieve about 8 miles of progress. Luckily, navigation was no problem as our outbound tracks remained distinct even in poor visibility. Two more days brought us home, to our immense relief!

After the euphoric “refuelling” with unlimited hot drinks and treats to eat, the first task was – batteries! We had a second Briggs and Stratton charging set, identical to the one that had failed us “out there”. We set it up and started it – and it produced no output! Exactly the same symptoms as its twin. But here at home we had a far more extensive set of tools and equipment to investigate the problem. We still could not find it. Reference by radio to other more professional expertise could not help. We had to start thinking that with two identical sets of symptoms we must be at fault ourselves, overlooking something trivial. Meanwhile, how would we charge the batteries we needed?

Score: 5 – 1

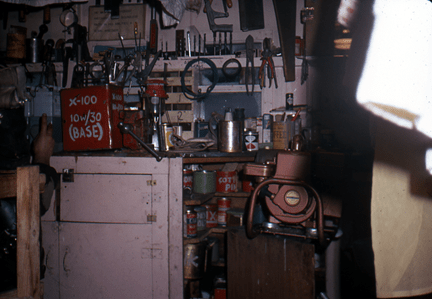

The main source of electrical power on the base was a small generator driven by an air cooled Petter diesel engine, producing mains 240v AC mainly for lighting purposes, but also to run a 12v DC charging unit for Muskeg, radio and other batteries. A secondary lighting circuit and various meteorological instruments ran from a battery bank in the “workshop”. What we had to do first, then, was to run the diesel to get some battery power. Now diesels, even basic ones like this, are tricky beasts compared with petrol engines. There had been problems during the summer with unexplained oil consumption, and we had been advised to run it sparingly until the oil question was understood. But now we needed it. I started it up after a bit of a tussle, with the temperature now fortunately above the freezing point of diesel fuel, and we were all relieved to get the batteries on charge again.

Score: 1 to us 5 – 2

Next day was spent largely on poking about with the second Briggs and Stratton. No progress, despite further expert input by radio from far away. But the day after that, unbelievably, the set worked perfectly! The only change we had made was to bring the thing indoors, where perhaps it dried out more than in the weather outside the “house”. It was reassuring to find at last that we could make the system work, given enough encouragement.

Score: 1 to us 5 – 3

But not for long. The petrol engine became reluctant to start. We needed to strip and reassemble the carburettor; to chase a significant oil leak; and Andy even had to remove the cylinder head and regrind the valves before we had it running reliably.

Score: 1 to the Gremlins, 1 to us, 6 – 4

All this activity in maintaining our equipment had used up many of the remaining days with enough daylight for field operations before the winter set in. We still needed to rescue the abandoned Muskeg before then, if possible. And here, for once, we had a positive piece of luck. Stationed at the base was a second field-capable Muskeg, which was not intended to be put to use in the coming season. During the summer the team stationed at the base for aircraft operational support had done a major service on this machine, as much for “something to do” when there was no flying (because of weather or other logistics) as for anything else. The service was not quite complete when they had to leave in the autumn: one of the two tracks was still missing many of its running plates that bore the weight of the vehicle on to the travelling surface.

However, during the period when we were grappling with those Foxtrac and charging set Gremlins, Mike Bell took it on himself to continue with replacing the missing plates. This was an extraordinarily selfless “something to do”, involving heavy steel levers, nuts, bolts and spanners out in the open at temperatures between -20˚ and -30˚C. He actually managed to complete the task well enough by the time we had at last resolved our other problems to make a rescue journey possible. It allowed us to plan a significant sledge caravan with enough equipment to give the best chance of successfully retrieving the stranded items.

Score: 1 to us, 6 – 5

And that is basically what happened; and in the process we were able to hit back at the Gremlins through the extra load-carrying capacity given by the unexpected second Muskeg.

Also stationed at the base was a space heater used by the aircrew to enable the petrol aero engines of the previous Otter aircraft to be started up in extreme cold conditions. (Gas turbine engined light aircraft were still a rare novelty in those days.) This amazing device was in a cabinet of about the size of a chest-freezer. The main parts were a rotating fan driven by a petrol engine (!) with a burner and heat exchanger in an air duct. Flexible plastic hoses led heated air from the duct to wherever it was required around the device to be started. To make sure the internal motor could itself be started in the cold there was a neat methylated spirit based preheater wick around the relevant parts.

This was the only prime mover that never gave us any trouble during the two years I spent at the Bluff. It solved the problem this time. The second Muskeg trundled away driven by Andy and Mike Elliott, pulling the heater as part of the cargo on the sledge, leaving Mike Bell and me behind at the base. And, having reached the abandoned vehicle and camped for the night, they were able to start up both Muskegs and bring everything home, retrieving all the various jettisoned items, sledges, tents etc. along the way. So we were at last well enough set to experience the oncoming winter.

Score: 1 to us 6 – 6 Result!

But the Gremlins hadn’t quite finished with us yet. The main power supply was going to be needed for the winter, and needed some further attention after its summer working season. We needed it for battery charging, of course, but it also provided mains voltage for lighting (nice to have!) and auxiliary equipment.

I was elected as “diesel mech”, having a bit of experience handling diesel engines on construction sites. In those days diesel cars were very unusual and skills in managing them were rare amongst the public. I successfully did an oil change and cleared out the fuel pipes, investigating a possible change of fuel tank. I started up the engine in the normal way, rumbling and vibrating as usual as it settled down. But to my horror I saw a spanner left lying, now sliding down the casing of the cooling air intake. I lunged to grab it – too late! It vanished into the intake and the engine shrieked to a halt in a cloud of sparks.

Score: 1 to Gremlins 7 – 6

Now what? First: get the casing off. Badly dented and holes torn from the inside, but still in one piece. Next: visible damage to the engine? Two cooling vanes snapped off the flywheel, not apparently crippling. Then: mobility? Engine turns OK, quite as freely as ever. Hmm, could be worse? But go and own up to the other three guys. Humiliation!

So now I straightened out and mended the casing as well as could be done, replaced it, and carefully started up again. No problem with the engine, but when running at normal speed it swayed significantly, hunting on its bearings. Flywheel out of balance! Would this cause secondary damage? Better get some advice. On the evening radio schedule I could speak to Barrie Whitaker and John Newman, respectively diesel-mech and tractor-mech at Adelaide. They couldn’t commit to anything seriously without an examination of the situation, and unsurprisingly their advice was not to use the generator unless really necessary. We should save it to cover any possible necessity later on. I still can hear the ringing voice of Barrie (from Accrington): “I reckon you’ve f—–d it, Georrrge!”

Yes. So we had to pass the winter’s night without mains power, apart from Midwinter’s Day when we indulged in the customary Antarctic celebrations under full power. The generator rig survived. The rest of the time we used Tilley kerosene lamps and the 12v lighting circuit, thanks to the working Briggs and Strattons. We all agreed afterwards that it worked just fine. It let us feel that we were part of the Myth, the Heroic Age, and not just the victims of somebody’s incompetence. Well, I would think that, wouldn’t I?

George Kistruck – Glaciologist/OIC – Fossil Bluff 1969 and 1970