Early Exploration in Marguerite Bay – Richard Barrett & Steve Wormald

Marguerite Bay lies on the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula to the south of Adelaide Island and to the northeast of Alexander Island around 68ºS 68ºW. The exploration and subsequent surveying and mapping of the Bay area has been hugely influenced by the presence or absence of the annual sea ice. A three degree celsius rise in average temperatures in the Antarctic Peninsula over the last half century has seen a 60% decline in Marguerite Bay sea ice. This is in contrast to the slight increase experienced by the remainder of Antarctica.

1819-21 Russian Naval Expedition

Admiral Fabian Gottlieb Thaddeus von Bellingshausen in his ships ‘Vostok’ and ‘Mirnyi’, on a circumnavigation of Antarctica.

Bellingshausen was born in Saaremaa, Estonia, in 1779 and joined Kruzenstern’s circumnavigation of 1803-6 as fifth officer. He demonstrated great ability and in subsequent years rose to the rank of Admiral in the Black Sea fleet. He was chosen to lead the 1819-21 expedition to complement the Antarctic voyage of James Cook 1772-5. Bellingshausen was to command the expedition with Captain Zavadovski on the ‘Vostok’, a 3-masted frigate of 985 tons and 130 feet overall, built in St Petersburg in 1818. ‘Vostok’ was unusual in having 3 decks, with heating in the tween decks and having a sauna. Captain Lazarev on the ‘Mirnyi’, a 3 masted sloop of war of 530 tons and 120 feet overall, built in the Lodejno-Pol’skoj shipyard. Bellingshausen left Kronstadt on 13 July 1819. They extended Cook’s exploration of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands and on 27 January 1820 sighted the coast of Antartica at 69.35 S 02.23 W, but failed to recognise that the ice covered coast was in fact land. (This was 3 days prior to Bransfield’s sighting of Trinity Land) The expedition wintered at Port Jackson (Sydney) and explored South Pacific islands before continuing the circumnavigation of Antarctica. They discovered Peter Island 20 January 1821.

Continuing from History Page:

27 January 1821 – The first close approach to the Marguerite Bay area was by the Russian exploring expedition. They sighted and named Alexander Land from the NW but fast ice prevented approach closer than an estimated 40 miles and the bad weather then forced him northwards. In the sea, now named for Bellingshausen, the winds are predominately westerlies making the west coast of the Antarctic peninsula a lee shore.

The expedition met up with Nathaniel Palmer in the ‘Hero’ and with other American sealers while they charted the South Shetland islands. Only Captain Lazarev had any English so their conversation was limited and not recorded in Palmer’s Log. Accounts of their conversation were recounted by Edmund Fanning in his book of 1833 and by Palmer’s niece in 1907, 86 years later. Which party sighted what and when has been the subject of various claims over many years. Bellingshausen’s account was published in Russian in 1831 and subsequently translated into German, but only became available in English in 1945. (For Polar book collectors, a Bellingshausen 1st edition in Russian complete with atlas is on sale for $325,000)

1830 – 1833 Enderby Brothers exploration and sealing expedition

John Biscoe on ‘Tula’ and George Avery on ‘Lively’

John Biscoe entered the Royal Navy as a volunteer in 1812 and served in several fighting ships during the 1812-1814 war with the United States, including the ‘San Domingo’ and ‘Colibri’, reaching the rank of acting master of HMS ‘Moselle’ in 1815. After the war he joined the mercantile marine. The whaling company Samuel Enderby & Sons appointed Biscoe, at 36, as master of the brig ‘Tula‘ and leader of an expedition to find new sealing grounds in the Southern Ocean.

(Enderby Brothers was the firm that had sailed into Boston Harbor with a cargo of tea in 1773, thus triggering the “Boston Tea Party” and the American War of Independence).

Accompanied by the cutter ‘Lively’ (82 tons), the ‘Tula‘ (148 tons) left London and by December 1830 had reached the South Sandwich Islands. The expedition then sailed further south, crossing the Antarctic Circle on 22 January 1831, before turning east at 60°S.

A month later, on 24 February 1831, the expedition sighted bare mountain tops across the ocean ice. Biscoe correctly surmised that they were part of a continent and named the area Enderby Land in honour of his patrons. On 28 February, a headland was spotted, which Biscoe named Cape Ann; the mountain atop the headland would later be named Mount Biscoe. Biscoe kept the expedition in the area while he began to chart the coastline, but after a month both he and his crew’s health were deteriorating. The expedition sailed toward Australia, reaching Hobart, Tasmania in May, but not before two crew members had died from scurvy.

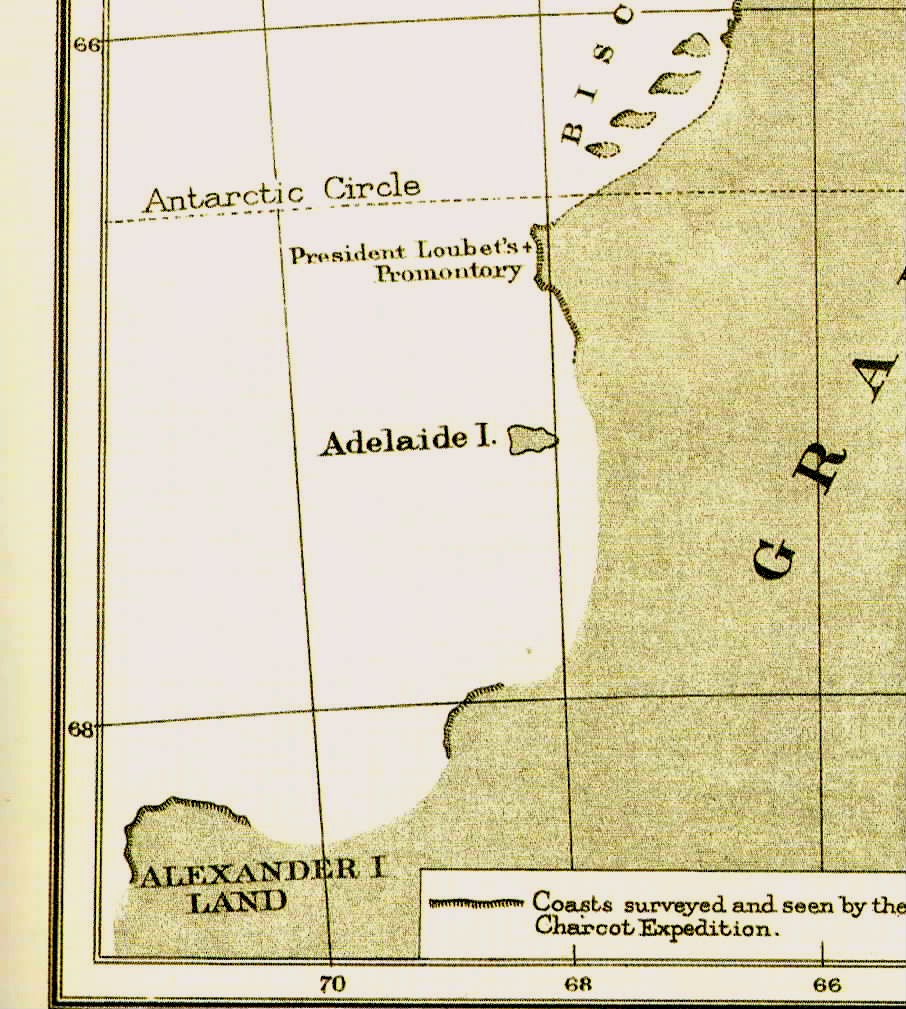

The expedition wintered in Hobart before heading back toward the Antarctic. On 15 February 1832, Biscoe sighted an island with high peaks above the clouds, surrounded by snow slopes, ending in ice cliffs going down to the sea. He estimated the island to be about 4 miles from north to south (actually 85 miles), and named it Adelaide Island after his Queen. Fast ice and rocks prevented a close approach. Sailing north, two days later ‘Tula’ sighted the island group, now named after him, the Biscoe Islands and landed on Pitt Island. A further four days later, on 21 February, more extensive coastline was spotted. Surmising again that he had encountered a continent, Biscoe named the area “Graham Land”, after First Lord of the Admiralty Sir James Graham. Biscoe landed on Anvers Island and claimed to have sighted the mainland of the Antarctic continent.

Biscoe again began charting the new coastline the expedition had found. By the end of April 1832 he had become the third man (after James Cook and Fabian von Bellingshausen) to circumnavigate the Antarctic continent. On the journey home, ‘Tula’ was driven aground on Livingstone Island abandoned but later re-floated, and the ‘Lively’ was wrecked in the Falkland Islands. The expedition, with no hope of a profit, headed home in the ‘Tula’ with a crew, after deaths and desertions, of only 4 men and 3 boys, reaching London in early 1833.

1893-1894 Norwegian sealing expedition

Carl Anton Larsen on ‘Jason’, Morten Pedersen on ‘Castor’ and Carl Julius Evensen on ‘Hertha’

Larsen visited the South Shetland Islands and Hertha explored to the south. Larsen discovered King Oscar II coast, Foyn Coast and Robertson Island, reported a volcanic eruption at Seal Nunataks, penetrated the Weddell Sea coast of the Antarctic Peninsula to 68.17ºS and made the first collection of fossils and the first use of skis in Antarctica.

22 November 1893 – Carl Evensen, in the sealing vessel ‘Hertha’, sailed inside the Biscoe Islands and almost reached Charcot Island at 69.1ºS 76.2ºW. En route he sighted Adelaide Island and Alexander Island but again fast ice prevented a closer approach. This voyage, so early in the season, indicates the variability of the sea ice, but Evensen was hunting seal, not new geographical discoveries.

3 August 1895 Sixth International Geographical Congress

Meeting in London the Congress adopted a resolution “…that the exploration of the Antarctic Regions is the greatest piece of geographical exploration still to be undertaken…” It was also resolved that the governments of the leading countries should be urged to equip expeditions for this purpose. Great Britain and Germany took up the challenge with the Scott and Gauss expeditions, and five private expeditions also sailed south. These were the Belgian, de Gerlache, the Norwegian/Australian Borchgrevink, the Swedish Dr Nordenskjold, the Scottish Dr. Bruce and the French Dr. Charcot.

1897 – 1899 Belgian Antarctic Expedition

Adrien De Gerlache, in ‘Belgica’, was notable as being the first expedition to the Antarctic of a purely scientific nature, and was the first time that anyone had over wintered south of the Antarctic Circle.

(A group of sealers had involuntarily wintered on King George Island in the South Shetlands in 1821 after their ship, ‘Lord Melville’, was blown off course in a storm and rescue was not possible until the next summer)

It was also an unplanned winter, perhaps not for the expedition leader de Gerlache, but for the rest of the men there was neither intention nor notice of overwintering. De Gerlache made important discoveries in the north of the Peninsula, and when sailing south at 69.8ºS 70.6ºW sighted Adelaide Island and Alexander Island, but once more fast ice prevented approach. The ship’s complement included Roald Amundsen (first at the South Pole) and Dr. Cook (who later claimed to be first to the North Pole and the first ascent of Mt. McKinley).

After much late season surveying, the ship was iced into the pack on the 3 March 1898. The disparate crew, with their several nationalities and languages, started the winter well, keeping themselves as busy and making themselves as cosy as they were able. This did not last very long however, as unprepared for the winter as they were, they had insufficient equipment and supplies to keep them comfortable, occupied or properly nourished. On 21 March 1898 Cook wrote:

“We are imprisoned in an endless sea of ice… We have told all the tales, real and imaginative, to which we are equal. Time weighs heavily upon us as the darkness slowly advances”

All of these factors took their toll on the men and by the 19 May, when the sun disappeared below the horizon for the start of the long Antarctic night where it would not be seen again for another 63 days, their plight was starting to become desperate.

The return of the sun on the 22 July lifted the men’s spirits, but illness still prevailed, de Gerlache and Lecointe wrote their wills and took to their beds able to do little else. Two of the crew, Tollefsen and Knudsen started to show signs of mental illness and morale in general was at rock bottom, Cook (the ships surgeon) also noted heart irregularities in several of the men, scurvy was rife by now. A particularly bitter blow was the death of the ship’s cat “Nansen”, once bright and friendly, the cat too became withdrawn, would growl at people and eventually faded away to excessive sleep and then death.

Cook and Amundsen then took command as de Gerlache and Lecointe were unable to fulfil this role due their illness. Cook in particular reversed their fortunes by retrieving the frozen penguin and seal meat and making sure that each man ate some each day and spent some time in front of the fire. He improved morale by not allowing them to become totally introspective and organising complicated games – huge sums of imaginary money were gambled in card games. Even de Gerlache began to eat the meat that he had previously hated so much, slowly the men all recovered their health and to some extent, their spirits. By 31 July, Lecointe was sufficiently recovered to be able to join Amundsen and Cook on a sledging trip away from the confines of the ship.

As spring came, the health of all returned due to the fresh meat, but the ‘Belgica’ was still trapped in the ice that was now about 7 feet (2.1m) thick around the ship. By January, the possibility of another winter in the ice was becoming real. Explosives were used to try and blast a passage out or split the flow they were stuck in – open water was about half a mile away. Cook suggested that two trenches should be cut to open water from the bow and from the stern to try and speed the melting that was taking place. The trenches were duly dug and cut with saws and axes in what was a huge effort, on St. Valentines day, 14 February 1899, the ‘Belgica’ emerged from its frozen-in position. Loose (not frozen in) pack ice was still tight around the ship however and it was a month before it was free and able to head out into open sea, having been stuck for 13 months.

The ‘Belgica’ reached Punta Arenas, Chile on 28 March 1899 de Gerlache was feted as a hero in Belgium and France. Despite the difficulties, the ‘Belgica’ returned with an important collection of scientific data and the first annual cycle of observations from Antarctica. The stage was now set for later expeditions to winter in Antarctica with invaluable lessons having been learned.

1903 – 1905 – Charcot – French Antarctic Expedition

Jean Baptiste Charcot was born in 1867 in Neuilly-sur-Seine to a wealthy family. His father, a renowned neurologist, encouraged his son to train as a doctor but his main interest was the sea. A succession of larger and larger vessels extended his sailing from local waters to Jan Mayen in the Arctic. He studied bacteriology as he feared following his father’s career, and was very well connected socially. His father-in-law was Lockroy, Minister for the Navy, his sister Jeanne was married to the proprietor of Le Matin and his half sister Marie was married to Waldeck-Rousseau, Prime Minister of France 1899-1902

Charcot led and financed the French Antarctic Expedition with the purpose built ship ‘Français’. The ship was a relatively small 3 masted schooner of 250 tons and 105 feet overall, but was “exceptionally well built of first class materials”. On the advice of de Gerlache, whom Charcot consulted, the ship was strengthened at the waterline with transverse beams, the bow was reinforced with iron. The Achilles heel however was a poor quality engine that at 125 hp underpowered the ship.

The expedition departed Le Havre 15 August 1903, in haste, to help the search for the Nordenskjold expedition but the Swedish party was rescued by the Argentine corvette ‘Uruguay’ while the ‘Français’ had just reached Buenos Aires. ‘Français’ visited Smith Island in the South Shetlands and then coasted the Palmer Archipelago, struggling with the engine. They discovered and named Port Lockroy before finding a site to winter the ship on Wandel Island. It was not until 25th December 1904 that they were able to escape the ice and head south, but soon met with very bad weather.

15 January 1905 – ‘Français’ ran aground south west of Adelaide Island, within sight of Alexander Island, and Charcot had to retreat northwards sighting the coast of Loubet Land to the east. The ship was badly damaged, with the engine unusable, the crew worked 3 man shifts pumping 45 minutes every hour, but made it to Puerto Madryn, Patagonia and finally back to Buenos Aires where ‘Français’ was purchased by the Argentine government to support their Laurie Island meteorological station.

During this season the Argentine corvette ‘Uruguay’ headed south to check on the expedition but finding no trace, pronounced the expedition lost. While in the Antarctic, Charcot was divorced for desertion by his first wife Jeanne, a grand-daughter of Victor Hugo.

1907 – Charcot married Marguerite “Meg” Cléry. She was a painter and illustrator who accompanied him on some of his voyages and was constantly supportive. At the end of the year their daughter, Monique, was born.

1908 – 1910 French Antarctic Expedition

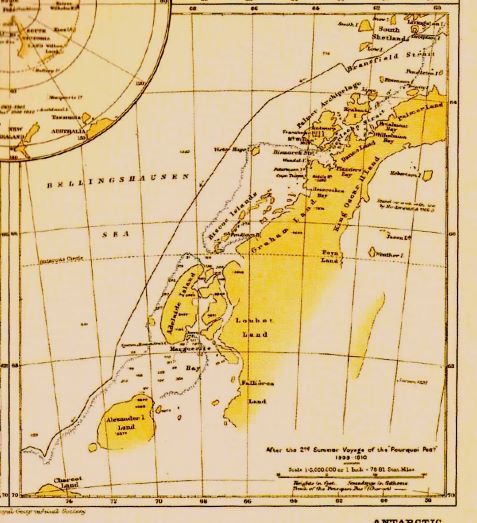

Jean Baptiste Charcot’s second expedition had a much easier time in raising finance and another new ship was constructed, a 3 masted barque of 445 tons and 131 feet overall. Charcot named the ship rather whimsically ‘Pourquoi Pas?’ (Why not ?) it was Charcot’s fourth ship bearing this name. The ship was equipped with a crow’s-nest and with a telephone to the bridge. With the object of extending the work of the first expedition, they left Le Havre on 15 August 1908 reaching Deception Island by Christmas Day which now hosted a thriving whaling station. They travelled south to their previous wintering station on Wandel Island but on 1 January 1909 found a wintering location on Peterman Island able to accommodate the extra length of ‘Pourquoi Pas?’. Using the ships launch Charcot explored the Berthelot Islands but became trapped by ice. Bongrain in ‘Pourquoi Pas?’ came to the rescue but on the return trip they ran hard aground on a submerged reef. After 24 hours hard labour they escaped and returned to Peterman Island to re-stow the cargo that had been shifted to raise the bow. In early January they set off to explore southwards, charting Pendleton Bay and Martha Bay and skirting Adelaide Island.

15 January 1909 – Charcot, in ‘Pourquoi Pas? ’ rounded the southern cape of Adelaide Island and named it Cape Alexandra after the royal spouse of Edward VII. This was in honour of the English Captain John Biscoe who had discovered the island.

Charcot named the bay after his wife Marguerite, and Jenny Island after the wife of second officer Bongrain.

A sledge journey north in Laubeuf Fjord indicated that Adelaide Island was indeed separate from the mainland. Charcot approached within 3 miles of Alexander Island and added detail to the chart but was hampered by ice and weather. Unable to find a place to winter he headed north and wintered on Peterman Island. In November 1909 the ship returned to Deception Island and collected mail and coal from the whalers. ‘Pourquoi Pas?’ was making 2 tons an hour from leaks due to the grounding and the whalers supplied a diver to examine the damage, which was severe, but Charcot did not disclose this information to the ship’s company. Charcot returned south in 1910 but, reluctant to enter the ice with a damaged ship, he turned away from Marguerite Bay. Following the ice edge SW he discovered Charcot Land which he named after his father, and sighted Peter Island before heading for home, pausing in Montevideo for repairs to the hull.

1928 – 1930 The Wilkins-Hearst Expedition

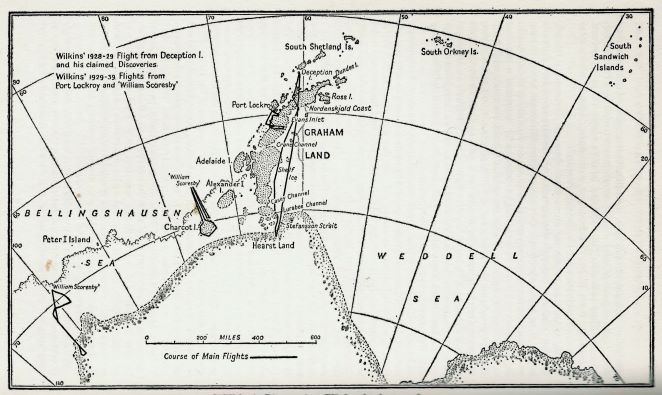

George Hubert Wilkins was an Australian pioneering aviator who was knighted after completing a flight from Port Barrow, Alaska to Spitsbergen. Equipped with two Lockheed Vega aircraft supplied with wheels, floats and skis they were transported to Deception Island by the whale factory ship ‘Hektoria’. There were two pilots, Carl Ben Eielson and Joe Crosson, also an engineer and a radio operator. The sea-ice in Deception was not suitable for skis and the water had too much ice for floats. A runway was therefore made by hand on the volcanic ash foreshore.

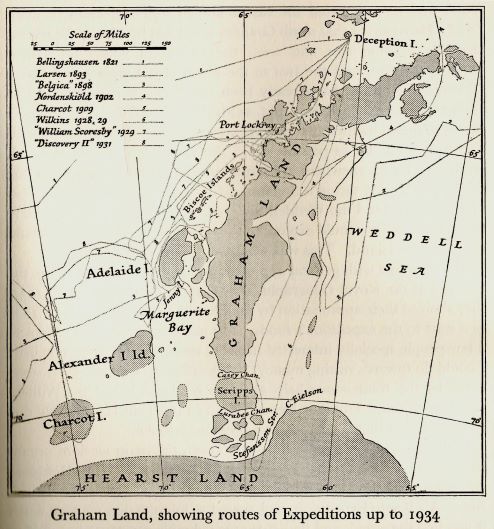

28 November 1928 saw the first aeroplane flight in Antarctica from Deception Island by the Wilkins expedition. (Read the full story HERE.) A flight down the East Coast of the Antarctic Peninsula gave the mistaken impression of a series of islands separated by ice filled straights. The planes were left at Deception for the winter. The Discovery Committee were so impressed by Wilkins accomplishments that they offered the ‘William Scoresby’ for his use in 1929-30. Eielson had been killed in Siberia and Crosson opted out, so two new pilots were obtained for the new season, Parker Cramer and Al Cheeseman. Flying conditions were no better at Deception in 1929 but flights were made off floats from ‘William Scoresby’ that year (1929) from Port Lockroy and Charcot Land was shown to be an island.

1933 – 36 The Ellsworth Antarctic Expedition

Lincoln Ellsworth was born in 1880 into a wealthy family in Chicago, he was an indifferent student and sent down from Yale. Working as a survey assistant in his father’s coal mine he nearly lost his life on a railroad hand-car. He was more successful studying railroad surveying at McGill and when his interests turned to Polar ventures studied under Mr. Reeves at the Royal Geographical Society in London. Ellsworth enlisted in the army for WWI and learnt to fly in France but caught the flu in the pandemic of 1918 and his recovery took 4 or 5 years. His father funded the attempt to fly to the North Pole with Amundsen in 1925 but died before the explorers returned. In 1926 Ellsworth and Amundsen with Umberto Nobile flew the dirigible ‘Norge’ from Svalbard to Alaska via the pole.

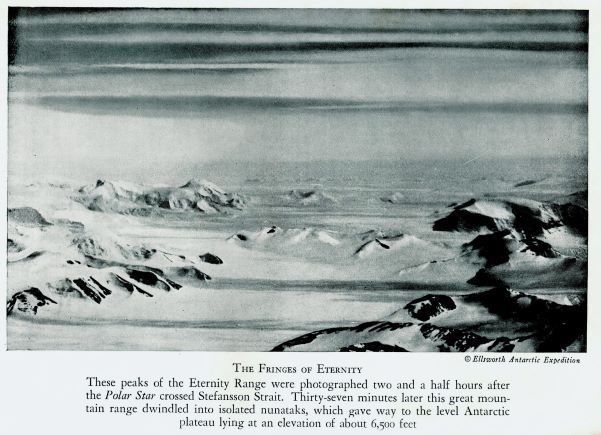

In 1933 Ellsworth turned his attention to the South Pole and teamed up with Hubert Wilkins. Aboard the ‘Wyatt Earp’ they sailed from Dunedin to the Bay of Whales, and unloaded their Northrup monoplane onto the sea ice which broke up overnight. The plane was recovered severely damaged ending operations for the season. The plane was rebuilt in California and the plans were changed to fly from Deception Island which they reached in October 1934, where there was enough snow for a runway. Turning the engine over by hand, resistance from oil in a lower cylinder was sufficient to break a con-rod, and there were no spares. Pan-Am flew spares to Magallanes where they were picked up by the ‘Wyatt Earp’, but by the time they returned to Deception all the snow had melted. They relocated to Snow Hill Island where the pilot Balchen had reservations and after a flight south of one hour turned back, ending flying operations for another season. In 1935 Ellsworth returned with a new pilot Herbert Hollick-Kenyon and they set up base on Dundee Island where they found a firm snow surface for a runway. After two trial flights on 21 November they flew south past Wilkins’s Stefansson Strait and sighted the Eternity Range before turning back.

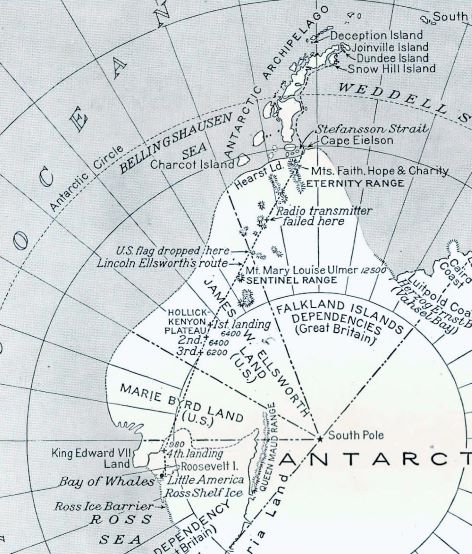

22 November 1935 – Ellsworth made the first powered flight across Antarctica from Dundee Island, appearing to confirm Wilkins mistaken impressions, and discovered the Eternity Range. They landed and camped four times en route to sit out bad weather, finally running out of fuel some miles short of Byrd’s Little America, which they reached on foot on 15 December. A month later ‘Discovery II’ arrived in the Bay of Whales and picked up Ellsworth who had a frostbitten foot. Hollick-Kenyon awaited the arrival of ‘Wyatt Earp’ whose crew used one of Byrd’s tractors to recover the plane.

A re-interpretation of the Ellsworth photographs by Joerg showed a conjectured fault depression separating Alexander Island from the mainland.

These two flights demonstrated the difficulty of putting features onto the map from aerial photography without adequate ground control points.

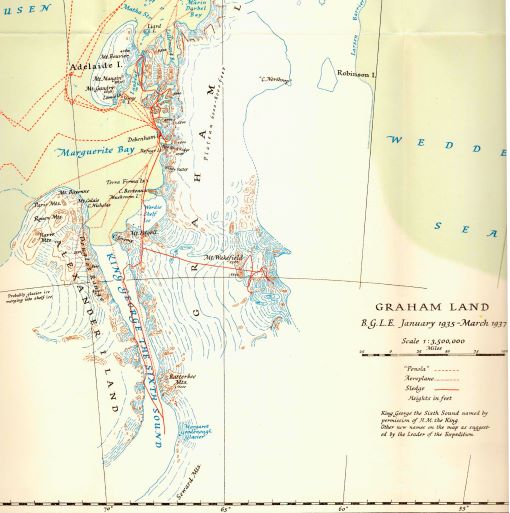

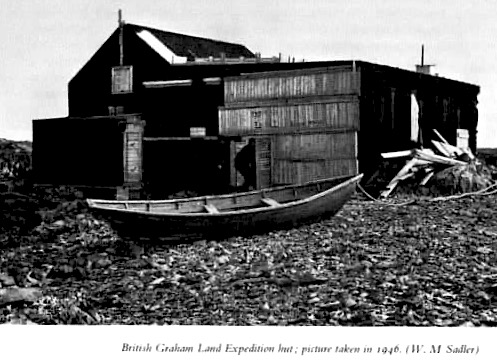

1934 – 37 The British Grahamland Expedition (BGLE)

John Rymill joined Gino Watkins’s 1930 British Arctic Air Route Expedition (BAARE) in Greenland and learned to understand the ice conditions with guidance from the Inuit people. He returned on Watkins’s second Greenland expedition and, following his leader’s death, took control of the expedition. Rymill was born at Penola, South Australian in 1905 and had always determined to be a polar explorer and to that end studied anthropology at the University of London. Like Ellsworth he studied surveying and navigation under Mr. Reeves at the Royal Geographical Society then snow and ice conditions in Switzerland and Scandinavia. He also qualified as a pilot and aircraft mechanic.

After returning from the BAARE expedition, in 1934 Rymill led his own expedition the British Graham Land Expedition to the Antarctic Peninsula on the ‘Penola’, an elderly three-masted topsail schooner of 137 tons and 102 feet overall, built in Brittany in 1908 for the Iceland cod fisheries. Fitted in 1931 with twin Junkers diesel engines, they had to pay £74 to get a Junkers technician to overhaul them.

BGLE planned to establish a base in Marguerite Bay and sledge through Stefansson Strait to explore the Weddell Sea coast with a second party exploring south of Alexander Island. Ultimately their work would prove that Graham Land was a peninsula of the main Antarctic continent, and not a series of islands and straights as believed by Hubert Wilkins in his aerial survey of 1928/29.

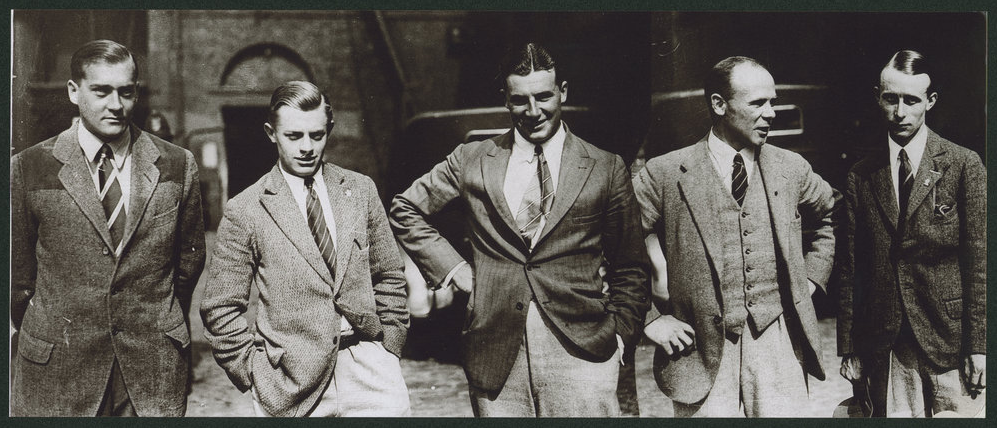

Rymill was joined in Antarctica by four of his companions from Greenland:

- Surgeon Lieutenant-Commander Bingham (“Doc”, “Ted”)) was the expedition doctor and also had charge of the expedition’s sledge dogs.

- W. E. Hampton (Ham) was one of the first to join Rymill for the Antarctic expedition. He served as Rymill’s second-in-command and was in charge of the flying operations. He had studied aeronautical engineering at Cambridge, and then worked for a further year with de Havilland’s. On returning from Greenland Hampton joined the staff at Vickers Ltd.

- Alfred (“Steve”) Stephenson had served as chief surveyor in Greenland and in Antarctica was appointed as chief surveyor and meteorologist.

- Quintin Riley was another of the first to join the Antarctic venture. He was in charge of stores and the two boats used by the shore party for coastal surveying and transport. He also served as one of the meteorologists. One of the boats – ‘Stella’, a motor launch – had been used in Greenland and was also used to sound the depths for the ‘Penola’, and also on occasion towed the schooner.

BGLE departed England on ‘Penola’ on 10 September 1934 and proceeded via Madeira and Montevideo to Port Stanley, where they met up with Hampton and Stephenson who had travelled with stores on a cargo boat and with Bingham who had bought huskies from Labrador. Discovery II carried heavy stores, 34 dogs and the de Havilland Fox Moth aircraft to Deception Island and on to Port Lockroy. The ‘Penola’s’ engines had gone out of alignment and were used sparingly, but arrived at Port Lockroy on 22 January 1935. Rymill made an exploratory flight in the Fox Moth and chose the Argentine Islands as a wintering site. ‘Penola’ ferried all the stores to the base site and was frozen in for the winter. The expedition explored the coasts and islands by sledge, launch and aircraft and proved that there were no straits through the Peninsula in this area. They were in radio contact with ‘Wyatt Earp’ at Dundee Island when Ellsworth confirmed the existence of Stefansson Straight. The expedition decided to move further south for the following year but ‘Penola’s’ engines were a problem. On 3 January 1936 the ‘Penola’ was freed from the ice and sailed north to Deception Island and the now abandoned whaling station. While there they used the workshop to realign the engines and scavenged some supplies of timber. Then they returned to the Argentine Island and picked up the expedition party before proceeding south around Adelaide Island.

24 February 1936 – The “Penola” entered Marguerite Bay and anchored in the Leonie Islands. After air reconnaissance John Rymill selected a base site at the Debenham Islands. Flights showed the country was very different from the existing information on the chart so they modified their plans accordingly. The repairs to the engines were unsuccessful and it was decided the ship should winter in Port Stanley and go to the whaling stations on South Georgia where Vestfolds Whaling Company refitted the engine beds. (While returning from South Georgia the ship received a radio message that Discovery II had lost contact with a party in a small boat at Esther Harbour and they joined the search. The party were found by Discovery II having spent 9 days under an upturned dinghy.)

An initial flight on 13 March to the SW of the base in the Debenham Islands showed no break in the coast until near to Alexander Island, no sign of Wilkins’ Casey Channel. Meanwhile the new base with aircraft hangar was under construction using salvaged timber and was completed on 23 March where the Fox Moth could be safe from winter storms. A second flight on 31 March to the north explored Bourgeois and Bigourdan Fjords and up a glacier which linked to Lallemand Fjord at all points finding no openings through the Peninsula. A flight on skis on 1 June to the south of Red Rock Ridge confirmed the sea ice and a depot journey set off with dog teams and a tractor. They had a bad time off Windy Valley and abandoned the tractor but found and named, the Terra Firma Islands. In July surveying and geology journeys was made to the north into the fjords and linking with Charcot’s Laubeuf Fjord survey. A flight on 14 August to the north tip of Alexander Island showed that the sea ice was broken in this area and not suitable for sledging.

A flight on 4 September entered King George VI Sound and flew to 70.5º S and on the return explored the Wordie Ice Shelf. Sledge journeys started the next day with 5 teams. On the Wordie Ice Shelf, Rymill and Bingham turned back to base, while Stephenson, Fleming and Bertram went south over the Relay Hills and down on to the Sound where, by 19 October, they reached 72ºS before turning for home. They made the first landing on Alexander Island finding fossil bearing sedimentary rock, shells and plant fossils at a site they called Fossil Bluff. They met Rymill and Bingham at Relay Hills and returned to base on 19 November. Rymill and Bingham had used the aircraft to fly in a depot to the Wordie Ice Shelf but when they returned only 2 inches of the depot flag was visible, which they recovered then sledged up to the Relay Hills. The original plan had been to sledge west towards Charcot Island but they found no route through Alexander Island so the plan was changed to go east across the Peninsula towards the Weddel Sea. This route was a hard climb in soft snow and on 24 November they reached their highest camp at 7,500 feet by Mount Wakefield. They then explored the plateau and further mountains to the east before returning back to base, which was reached in early January 1937 after some very wet sledging over the last of the sea ice.

More flights had to wait until sufficient sea ice had broken out and the plane could operate off floats. This was achieved on 1 February 1937 and a photographic flight was made to Alexander Island along the Hampton and Sibelius Glaciers. A flight on 12 February was made to check on the sea ice which was sufficiently clear to send a radio message to the ship to pick them up. Another photographic flight was made on 13 February north up Laubeuf Fjord and into Marin Darbel Bay connecting with the previous years work from the Argentine Islands. They then returned flying south down Lallemand Fjord.

The launch ‘Stella’ went north to Horseshoe Island where they surveyed for an anchorage before heading across to Leonie Island to meet the ‘Penola’ which arrived on 23 February. They proceeded to Horseshoe Island but found the entrance to the anchorage blocked by ice and so went on to the base at the Debenham Islands. The work began to load the ship which was hampered by a seven day gale which sank the ‘Stella’. She was later recovered, and the expedition left on 12 March. After leaving Marguerite Bay and finding clear water the ship sailed SW for 70 miles hoping to reach Charcot Island but pack ice prevented this so the ship headed north to South Georgia. The scientific staff went home on the whale transporter ‘Coroda’ and after setting up the topmasts the ‘Penola’ left in early May, arriving back at Falmouth on 4 August 1937.

For the first time Marguerite Bay began to take on a recognisable form. Exploratory surveys were carried out by sledge wheel and compass traverses between star or sun-fix positions. A wireless receiver allowed the surveyors to receive accurate time signals from Washington or Buenos Aires. Plane-table equipment was used to carry out the detail mapping together with panoramic sketches and theodolite angles.

The expedition was equipped with a small de Havilland Fox Moth plane which could operate off floats, wheels or skis and was used for reconnaissance and for laying depots to support long journeys. The Williamson Eagle III air survey camera was used to take photographs specifically to assist the mapping, but the camera had to be hand held on long flights as the heavy camera mount used up too much of the aircraft’s limited payload.

The expedition is regarded as the most cost efficient of all time with a budget of only £20,000 which covered the ship, an aircraft, dog sledges and two bases. Their effective field operations showed the way for FIDS and BAS for the next 40 years.

NB Mt. Wakefield was found to be coincident with Ellsworth’s Eternity Range, which BGLE were not aware of, so Ellsworth’s names had priority.

Read more about BGLE on the Stonington page

These five men were the first polar explorers to receive polar medals with both Arctic and Antarctic bars after the British Graham Land Expedition in 1937. It is presumed that this cut-and-paste image was prepared, perhaps for newspaper publication, after they received their medals. This photograph was taken at St Katharine’s Dock, London.

(Photo: Courtesy of the State Library, South Australia)

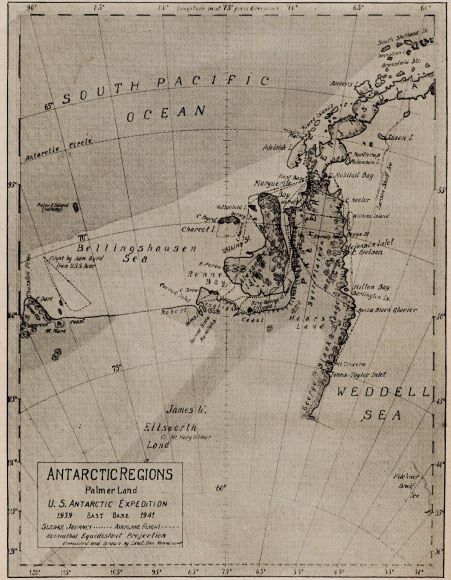

1939 – 1941 United States Antarctic Service Expedition (USASE)

Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd (USN)

The ‘Bear’ (689 tons, 190.4 ft. long) was completed in 1874 by Alexander Stephen in Dundee, and had already served 40 years in Alaskan waters as a USCG Cutter. In 1927, President Calvin Coolidge officially signed ‘Bear‘ over to the City of Oakland to become a historic museum ship. However, the venerable ‘Bear‘ was destined for greater glory. After the cutter’s retirement by the Coast Guard and its brief career as a floating museum, Richard Byrd re-activated the famous cutter. Byrd used ‘Bear‘ as one of two ships for his first Antarctic expedition in which he established the well-known research base at Little America. He returned home in 1930 and used ‘Bear’ on a second expedition in 1933. Byrd’s expeditions were the first American scientific missions to the Antarctic, and they resulted in advanced discoveries in weather, climate, and geography. All the while, Bear still relied on its 19th century sail rig and coal-fired steam engine.

In the late 1930s, President Franklin Roosevelt placed Rear Admiral Byrd in charge of the United States Antarctic Service and an expedition was organised with a West Base at the Bay of Whales, under Paul Siple and an East Base on the Antarctic Peninsula, under Richard Black. In 1939, Byrd employed ‘Bear‘ once again to reach his bases in the Antarctic. Prior to this cruise to the Antarctic, technological change had overtaken ‘Bear‘s’ original design and construction. ‘Bear’s’ coal-fired steam engine was replace with a modern diesel power-plant that no longer required a tall smoke stack, and ‘Bear’s’ barkentine rig was altered to support a scout sea plane. The ‘Bear’ was accompanied by the ‘North Star’, a wooden hulled ice cutter built in 1932 in Seattle for the Bering Sea Patrol. She was 86.6m (225ft) long, 12.5m (41ft) beam and 5.03m (16.5ft) draught and registered 1,434 tons, with a 1,500 bhp diesel engine, she had a maximum speed of 13 knots and range of 14,500 km.

After both ships established West Base in the Bay of Whales, ‘North Star’ went to Valparaiso for more supplies while ‘Bear’ followed the ice edge eastwards and Byrd explored using the sea plane, with both ships meeting up in Marguerite Bay.

5 March 1940 – Byrd, on ‘Bear’ and ‘North Star’, as part of the US Antarctic Service Expedition (USASE), entered Marguerite Bay and established East Base on an island that they named Stonington after the home port in Connecticut of Palmer’s sloop, ‘Hero’. The expedition was equipped with a Condor biplane, 75 dogs, 1 light army tank and 1 light artillery tractor. The aircraft was equipped with aerial survey cameras and exploratory flights were made as shown on the following map (fig 10). The aircraft was also used to fly in depots for the sledging parties but made the same mistake as BGLE and lost their depot on the Wordie Ice Shelf in deep snow.

USASE pioneered the route up the Northeast Glacier from Stonington to the plateau at over 5,000 feet, and established a plateau meteorological station to assist flying operations. They pioneered, with some success, the use of field radios for sledge parties, and they were able to supply field parties with aerial photographs of unmapped areas. From the plateau station they also pioneered a hazardous route down Bills Gulch to the Larsen Ice Shelf.

Sledge journeys were made to the SW by Ronne and Eklund following Stephenson’s route down King George VI Sound, then turned west and reached Eklund Island, so proving the insularity of Alexander Island. Dyer, Healy and Musselman sledged SE from the Relay Hills towards the Eternity Range. Knowles, Hilton and Darlington sledged over the plateau, down Bills Gulch and south down the East Coast of the Peninsula to 72ºS. Flights disproved the existence of any of the straits seen by Wilkins and Ellsworth and showed that the Peninsula was part of mainland Antarctica. Aerial photography was taken for mapping using the ground control established on the sledge journeys, but only the rudimentary map Fig. 10 was produced and the photography was not made available in the UK.

The probability of US involvement in the 1939-45 war forced the expedition to be curtailed in 1941. Ships could not approach because of heavy sea ice and the personnel were evacuated from the base by air to meet the ‘Bear’ at the Mikkelsen Islands where the Condor was abandoned (now renamed Watkins Island in the Biscoe group). The impending war saw the majority of the personnel called up for military service and only a limited number of their results have been published. Preliminary results were presented at a Symposium of the American Philosophical Society on 21 November 1941 and published in April 1945

(Having spent the winter of 1974 at Stonington, clearing up a considerable amount of abandoned USASE and RARE equipment, I was surprised to see in 1993 reports that the tank and tractor are still there, unseen in 1974 – Richard Barrett 26 January 2022)

The War Years 1939-45

Marguerite Bay was quiet during the 1939-45 war but further north on 8 February 1942, the Argentine ship ‘Primero de Mayo’ entered Deception Island and took possession of Antarctica between 25ºW to 68º34’W. The BGLE base in the Argentine Islands was also visited and an Argentine flag installed. In 1943 Primero de Mayo returned and visited Marguerite Bay. Legal advice to the British Foreign Office was that evidence of use and occupation was necessary to support disputed territorial claims. However, to avoid confrontation with Argentina, use of the territory by German forces was used as an excuse to patrol the area. In January 1943 ‘HMS Carnarvon Castle’ visited Deception (see story on “Ships & Mariners” page), removed all evidence of the Argentine visit, and hoisted a British flag. They then proceeded to enjoy a cordial visit to the Argentinian meteorological station on Laurie Island. A month later ‘Primero de Mayo’ returned to Deception and removed evidence of the British visit.

1944 – The British Admiralty instigated Operation Tabarin to confirm British sovereignty and established bases at Deception Island, Port Lockroy and Hope Bay. At the end of hostilities in 1945 this operation was transferred to the Falkland Island Dependencies Survey (FIDS). See related story here of the 1944-45 Voyage of the Newfoundland Sealing Ship Eagle” – Brian Hill (LINK)

FIDS

23 February 1946 – Surgeon Commander E.W. (Ted) Bingham of FIDS, formerly of BGLE, in ‘Trepassey’ entered Marguerite Bay which was now free of ice and established a second base on Stonington Island. Bingham was equipped with a Gipsy Moth aircraft, huskies and sledges for a programme of surveying and geology. The full story can be found on the Stonington page, Base E.

(Visiting in 1974 the San Martín base was derelict and with no evidence of the old BGLE base which had been intact in the late 1940s – Richard Barrett)

20 February 1947 The Chilean naval ship ‘Iquique’ visited Stonington.

12 March 1947 – RARE – Finn Ronne in ‘USS Port of Beaumont’ (1200 tons, 183 ft. long) occupied the old USASE buildings with his Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition (RARE). Ronne brought 3 aircraft and 43 huskies (they unfortunately suffered many losses to disease), a weasel tractor and rather controversially the first 2 women to winter in the Antarctic.

RARE was equipped with planes with Trimetrogon cameras capable of taking pictures from port horizon, vertical to starboard horizon which were excellent for producing mapping when coordinated ground control points were available. Extensive flights were made along the Weddell Sea coasts and across Alexander and Charcot Islands.

The 4 man joint US UK party lead by Duggie Mason and supported by RARE planes sledged down the east coast from 68S to nearly 75S where the Bowman Peninsula meets the edge of the Ronne Ice Shelf, travelling 1930km in 105 days. Exploratory surveying by sledge wheel and compass with sun azimuths at camp sites and minor details fixed by compass bearings. Aneroid heights were supplemented by sea level reading in rifts in the ice shelf. Panoramic photographs were taken at survey stations which proved invaluable when plotting the maps back in the UK. Features on the existing maps were found to be up to 80km in error.

More info on RARE

19 February 1948 – US Coastguard Cutter icebreakers USCGC ‘Burton Island’ (6,515 tons, 269 ft. long) and USCGC ‘Edisto’ (5,957 tons, 269 ft. long) arrived at Stonington through extensive sea ice to break out ‘Port of Beaumont’ which was still frozen in the ice at Stonington.

22 February 1948 – USCGC ‘Burton Island’ returned to accompany RRS ‘John Biscoe’ (1,554 tons, 220 ft. long) into Stonington with Vivian Fuchs as the new FIDS Base Commander and unloaded 65 tons of cargo overnight before the scheduled departure of ‘Burton Island’ on the 23rd. Heavy sea ice outside Marguerite Bay prevented the RRS ‘John Biscoe’ returning later in the season when it was planned to supply a new aircraft, and the sea ice was equally bad in 1949. It was not until February 1950 that the ‘John Biscoe’ returned with instructions to close the base, evacuating it by air if necessary.

8 March 1951 – Santiago Farrell, on ‘Santa Micaela’ of the Argentine Navy entered Marguerite Bay accompanied by the tug ‘Sanaviron’ and established a base on the Debenham Islands. In March 1952 they were relieved by helicopters from ‘ARA Bahia Aquirre’ and on 20 June 1952 the base suffered a major fire. In March 1953 they received supplies by an airdrop. The base was closed in 1960 and reopened in 1976. More info here: San Martín.

11 March 1955 – Ken Blaiklock, in ‘Norsel’, entered Marguerite Bay to establish a new FIDS base as the access to Stonington had been so difficult. He chose Horseshoe Island, with Gaul as base leader, equipped with huskies and sledges for a programme of meteorology, surveying and geology. The sea ice was very poor for travelling which confined their work to the island except for a short run to visit their Argentinian neighbours at Base San Martín. The full story of the occupation of Horseshoe Island (Base Y) is the on Horseshoe page.

The 1956 relief of Horseshoe by the ‘RRS Shackleton’ saw Searle promoted to leader but the sea ice was again bad for travelling.

Because of the difficulties of travel from Horseshoe a new base was established in early 1956 at Detaille Island at the entrance to Lallemand Fjord, with Tom Murphy as leader. They were equipped with huskies and sledges for a programme of Met, surveying and geology. The full story of the occupation of Detaille Island (Base W) is on the Detaille page. For information on Blaiklock Refuge: Blaiklock Refuge

1957 Relief at Horseshoe by the ‘John Biscoe’ included the installation of a refuge hut on Blaiklock Island but the winter saw good sea ice and the field work progressed well with another refuge at Orford Cliff to assist the Base W fieldworkers. For information on Orford Cliff Refuge: Orford Cliff Refuge

FIDS Director – Vivian Fuchs

A history of exploration in Marguerite Bay must include the effect that Vivien Fuchs had on its progress. Fuchs had wintered at Stonington in 1948 and 1949 and had conducted many extensive dog sledge journeys, together with Ray Adie (who inadvertently wintered for three consecutive years), and who eventually became head of Earth Sciences at BAS. Fuchs returned to the Falkland Islands Dependencies Scientific Bureau in London at the end of 1958. In 1962, with the introduction of the Antarctic Treaty, the FIDS was renamed the British Antarctic Survey (BAS). As its first Director, Fuchs built up an effective team of administrators and set about turning the Survey into a Public Office.

The Treasury proposed the closure of BAS, so Fuchs sought support from various Ministries, from the Royal Society, and from his now extensive network of influential contacts. The proposal to sustain BAS was put forward for consideration by the Cabinet Office and the Survey’s fate was referred to the Council for Scientific Policy, which advised that BAS should continue given the scientific output already proven. The Council also supported the need for a new ship for the Survey. Fortunately the Cabinet agreed and the BAS was formally transferred to the National Environment Research Council in April 1967, with an annual budget of £1 million (today about £12 million). At last a sustainable structure and continuity in the scientific programmes was possible.

A variety of research groups that included Geophysics, Biology, Medicine and Zoology were established throughout the country, some with research stations in Antarctica. BAS cooperated with the Scott Polar Research Institute at the University of Cambridge and in 1971 a BAS Glaciological Section was established there.

By 1971 the total number of men in the Antarctic was 92, including 45 scientists, surveyors and meterologists. By 1973 permanent staff in the UK numbered 53, increased each summer by an influx of contract staff being trained for Antarctic service, others writing up their research, and the additonal administrative staff required. In the UK it had long been planned to amalgamate the Head Office and various research groups scattered around the country, and so the transfer of the BAS to Cambridge was approved. In 1972 NERC agreed a site and sufficient funding, planning permission was granted a year later, and the BAS complex was operational by 1976.

During Fuchs’s 14 years as Director, the British Antarctic Survey had undergone a transformation. By the time he retired in 1973, the total number of staff was around 350 and the annual budget around £1.5 million (equivalent to about £8 million in 2022). With skill and vision Fuchs had guided the BAS from its political origins and emphasis on geographical exploration, to also become a world leader in Antarctic research.

1958 – Detaille Island (Base W) was closed at the end of that year as the poor sea ice had so restricted the work. Typically the sea ice stayed in and the base party had to sledge 30 miles to the ice edge to board the ‘John Biscoe’. One dog, Steve, obviously didn’t like the look of the Biscoe and escaped, turning up at Horseshoe Island base 60 miles away and three months later.

March 1958 – Stonington was reopened with Peter Gibbs in charge, equipped with huskies and sledges for a programme of surveying and geology.

7 March 1959 – It became clear that even with the assistance of US ice breaker ‘USCGC Northwind’, ‘John Biscoe’ could not break through the sea ice to reach Marguerite Bay. Stonington was closed and the party sledged over the sea ice to Horseshoe Island where they were picked up by US helicopters.

1959/60 – The season had plenty of sea ice which was bad news for the ships. The Argentine ice breaker ARA ‘San Martín’ had to rescue the Chilean ice-strengthend supply ship ‘Piloto Pardo’ but then lost a blade off its propellor and called in assistance from the US icebreaker ‘USCGC Glacier.’

‘Piloto Pardo’

The ‘Glacier’ then broke out ‘Kista Dan’ which was trying to relieve Horseshoe and establish a new base on Adelaide Island. The ‘Kista Dan’ was carrying an aircraft on deck, and tangled with the ‘John Biscoe’ on a tight mooring in the Argentine Islands which wrecked the aircraft.

South of the Argentine Islands an unbroken stretch of sea ice was located and the Otter aircraft at Deception flew down to meet ‘Kista Dan’. It then made several flights to Horseshoe to withdraw the party and take in a party of four who would then sledge south to Stonington for a seasons surveying. The Base E buildings were found to be in very poor condition, buried in ice which turned to flood water as the summer warmed up. The full stories of these bases and journeys are on the Horseshoe and Stonington pages in 1958 and 1959.

Exploration in the 1960’s and 1970’s

The 1960/61 season fortunately saw open water in Marguerite Bay. The ‘John Biscoe’ sailed into the Bay with a party of 12 to re-open Stonington and another party, initially intending to establish a base at Access Point (later renamed Rothera Point) on the south-east side of Adelaide Island, but were blocked from doing so by heavy pack ice. Instead a new FIDS base was opened at the most southerly point on Adelaide Island, together with men and materials to be flown into King George VI Sound for a new southern base, Fossil Bluff.

Adelaide Base T was established on 3 February 1961 and equipped with a tractor to help move materials. Read the full story of the establishment of Base T in 1961 on the Adelaide page. The Otter aircraft VP-FAK and VP-FAL flew down from Deception on 20 February 1961 to begin flying 23 tons of materials to Fossil Bluff. The three man party to winter at Fossil Bluff was flown in during March with a programme of geology.

Two Muskeg tractors for Fossil Bluff, being too large to fly in the Otter, were landed at Stonington together with materials for a new base hut at Stonington. The two Muskegs were to to be driven to Fossil Bluff over the winter sea ice.

In July 1961 a reconnaissance journey was made from Stonington as far as the Terra Firma Islands. They found a route and a depot laying journey began on 24 August which laid a fuel dump at the Mushroom Islands. They planned to return to base for fresh loads but became stranded on Compass Island as all the ice to the north went out. They returned to the Mushroom Islands and waited for the ice to reform and dog sledges to bring supplies from Stonington. They then travelled south as a joint party of Muskegs and dog sledges but one Muskeg was lost through the ice off Cape Jeremy. The Muskeg became bogged down and water spurted through the floor, Bryan Bowler jumped out and cut the sledge free and in two minutes he was looking into a pool of water with bubbles rising. They were able to carry on with one Muskeg hauling three sledges and reached Fossil Bluff on 24 November, 1961.

For the full story see the Fossil Bluff Base page, 1961

The following season two more Muskegs travelled to Fossil Bluff without incident.

The air facility at Adelaide Base was found to be very useful and it was expanded in the following years. Stonington and Adelaide were provided with Eliason motor-toboggans which were greeted with limited enthusiasm by the dog sledgers. The Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey was now re-organised as the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) though the personnel were still known colloquially as Fids.

Sea ice was obstructive to shipping in the 1963/4 season and the ‘John Biscoe’ was unable to reach the Adelaide base and instead unloaded stores on a rocky beach under an ice cliff 30 miles north. However bad weather prevented the immediate collection of the stores and much was lost. The construction of a small wharf at Adelaide began as a priority.

The resulting shortage of fuel at Adelaide meant that ‘John Biscoe’ was scheduled to make an early relief and arrived in clear water on 28 December 1964. The unusually mild spell reduced the ramp up to the airstrip to slush and the Muskegs were unable to manage the haul. A decision was made to land fuel drums on the sea ice and fly them up to the airstrip. This worked well for 20 trips and then VP-FAL crash landed on the piedmont above Adelaide Base and is there to this day. The other plane had been damaged earlier in the season, and was being used as little as possible, still had to retrieve surveyors and geologists from the field. In February 1965 the Biscoe returned for the main relief of Adelaide and Stonington and the unoccupied Horseshoe.

During the next decade or so Adelaide Base T continued a programme of meteorology and logistic support to the field parties and Fossil Bluff, while Stonington Base E maintained its programme of geology, geophysics and surveying, and was also the home of 100 plus huskies for the sledge teams.

During the winter of 1965 a party of surveyors from Stonington visited Detaille Island Base but were marooned when the ice went out. They were stranded and received air drops in October but were not picked up until the ‘Shackleton’ arrived on 25th. January 1966.

In May 1966 at Stonington the radio operator John Noël, and the diesel mechanic Tom Allan, sadly died on a leisure trip with two dog teams. The full story is detailed on the Stonington page, 1966. The bodies are buried on Flagstaff Hill at Stonington, where there is cross and Memorial plaque.

(Photo: Richard Barrett)

The 1966-7 season began with support from the Otter aircraft from Deception and later with the Pilatus Porter, the first turbo engine plane to be used. The Scott Polar Research Institute (SPRI) had developed airborne ice depth sounding equipment which was fitted into the Otter. Thus began a new field of study of measuring the depth of the ice cover. The equipment was later fitted in the Pilatus Porter and used to sound both the Larsen and Wordie Ice Shelves from altitudes ranging from 10,000 to as little as 15 feet. As the recordings measured both the surface and bottom trace this was a method of determining the surface elevation without the laborious heighting by surveyors. When the Otter returned to Deception it was retired.

For the 1967-8 season, with initially only one plane, the first task was to establish a line of food depots between Stonington and Fossil Bluff to enable a safe method of retreat for field parties, should it become necessary. The flying season proceeded with the single plane until the last pick up on 26 February 1968 which was from the Meiklejohn Glacier. During take off, a weld in the undercarriage failed damaging the skis. The pilot hoped to take off on wheels, but the wheel broke through the surface and the plane crashed. Unhurt the party and pilot sledged to safety at Fossil Bluff where they were forced to spend a very cramped winter.

With the possibility of no planes for the coming 1968-9 season Alastair McArthur, Base Commander at Stonington attempted an early relief journey to Fossil Bluff but this was prevented by bad sea ice.

More on this saga in The Cape Jeremy Affair and The Great Puffballs Rescue/Jolly stories on the Stonington page, 1968.

A second hand Otter VP-FAM had been procured from the Norwegian Air Force. This was shipped south the previous year but the volcanic eruptions at Deception meant that it had been landed in crates at South Georgia. These were now taken to Deception where it was assembled and flown to Adelaide. But on 3 March 1969 after a sudden power failure, it crash landed near Armadillo depot on the Plateau above Stonington with no injuries to pilot or passengers.

A new Twin Otter had been purchased and the greater range of this aircraft meant that it could be flown, in numerous stages, from Toronto to Adelaide. This was to become the new normal, wintering the planes in Canada (their summer) and flying them to Adelaide. The new plane’s first task, on arrival at Adelaide, was to take 8 men and a cargo of rations to Fossil Bluff. The full story of this flight and ensuing problems is detailed on the Adelaide page, 1968, “The Larsen Ice Shelf Incident”

The field programs designed by the Heads of the various departments in the UK created the need for extensive travel as the work areas moved further south. Each additional field scientist created the need for an additional General Assistant; and two new dog teams. The 1969-70 season was a very good weather year at Stonington, allowing extensive surveying and geological journeys, with ten dog teams covering 20,000 miles. Over successive years, starting at Horseshoe in 1955, when there was one Surveyor and one Geologist, with two dog teams, the programs steadily increased until, in 1973 there were 2 Surveyors, 3 Geologists, two Geophysicists, and 14 dog teams.

The early 1970s saw an almost regular pattern of activity with surveyors, geologists and geophysicists at Stonington with their dog teams and glaciologists at Fossil Bluff with their Muskegs and skidoos. All were supported by Adelaide who handled meteorology and logistics. Relief from the ships went without disruption and aircraft travelled down for the summer season from Canada.

Various medical emergencies and evacutions took place in these years of extensive travel, which are detailed on the Stonington page of this website, including the treatment and evacuation of John (Rock) Hudson (Stonington 1972) and serious problems in 1971 at Fossil Bluff where in the four man party one fell ill with liver damage. The nearest doctor was Dr. Mike Holmes at Stonington, he consulted by radio and was backed up by medical officers in Stanley and London. The Argentinians came to their assistance with an air evacuation to Buenos Aires where both men recovered. In December, Mike Holmes was at Adelaide on route home when Malky Macrae suffered a serious eye injury which caused him to lose all the fluid from his eyeball. With the doctor on hand he was successfully treated before heading home to make a full recovery.

Fuchs, with Dr. Adie, retained his support for travel using dog teams as the safest, if not always the most efficient, method of extending the work already performed in topographical survey, geology and geophysics. The programs put in place, and the increasing number of scientists in the field each year, came with instructions to Base Commanders to continue and increase the husky breeding programs to be able to place more teams in the field, firstly to keep up with the increasing number of scientists being deployed to the field programs, and secondly to work towards achieving the safety of field personnel operating in two-man parties with two dog teams. Veterinarians were deployed to investigate and monitor the health of the dogs, including in 1973 when Veterinarian Dr. R.W. (Bob) Bostelman wintered at Stonington as a Vet/GA, and drive his own dog team.

With the retirement of the now Sir Vivian Fuchs as Director of BAS in 1973, considerable changes were implemented during 1974. More info on Fuchs: Sir Vivian Fuchs.

New BAS Director – Dick Laws

Unlike Fuchs, the new Director, Dr. R.M. (Dick) Laws had no experience in dog team travel, and no interest. Laws came from a zoology background in Fids and then BAS, his major interest and published papers being related to seals. (Sledging Fids also had a great interest in seals, but in this case, as an augmentation to dog food on extensive journeys, and the occasional seal steak for the men).

Laws had joined Fids as a Biologist in 1947, had been Base Commander at Signy in 1948-50, and South Georgia in 1951-52. He became Head of Life Sciences for BAS in 1969, after various other careers. Laws toured the BAS Bases in the 1973/74 summer, including the Marguerite Bay bases. He intimated while at Stonington his dislike for the dog teams and the apparent deleterious effect they were having on the environment. During 1974, it was announced that dog travel would be discontinued, and Base E at Stonington Island was closed in February 1975 and is now maintained by the UK Antarctic Heritage Trust – UKAHT).

Base T on Adelaide Island closed in 1977 and was transferred to Chile. It is now operated as a summer only base named ‘Teniente Luis Carvajal Villaroel Antarctic Base’.Jerome and Sally Poncet wintered nearby on Avian Island in 1978 aboard their yacht Damien II and carried out important ornithological work. For more details of her life and career: Sally Poncet

Rothera Station, known as Rothera Point until 15 August 1977, was established as Base R in 1975 to replace Adelaide, as the glacier ski-way at Adelaide had deteriorated rendering the operation of ski-equipped aircraft to be hazardous. A party camped at Rothera Point in the 1975/76 austral summer to open up the air facility, and a small base hut was established for the first winter in 1976, with a four-man wintering party. The full stories of this first summer, winter and subsequent years are told on the Rothera page.

There was a phased construction programme so that by 1980 the station provided accommodation, electrical power generation, vehicle workshops, scientific offices and a store for travel equipment. During the 1980s the male only staff policy was abandoned and women began to take on many roles in BAS, culminating perhaps in 2013 when Professor Dame Jane Francis was appointed Director of the British Antarctic Survey.

From Rothera’s inception to the 1991–92 austral summer season, BAS Twin Otter aircraft used a glacier ski-way which was 300m above the station on the Wormald Ice Piedmont. During that summer a gravel runway and hangar facility was commissioned bringing a more reliable air operation and also the possibility of a passenger aircraft link from outside the continent. Before that everyone coming to Rothera had to be shipped from the Falkland Islands. A new wharf was constructed which allowed the relief ships to moor alongside – no more transhipping cargo to shore by scows and Fid-power, as cargo could now be containerised.

The new BAS air facility was available for use by other nations and was used, for example, as a staging post for a mid-winter medi-evac from Pole Station. It was the site of a fatal accident in 1994 when a Twin Otter, undertaking radio echo sounding for the Italian Antarctic program, crashed on take off into an iceberg that had drifted to a position just off the end of the runway – details on the Rothera page, 1994.

Today the development of the Rothera site continues. This is not an expansion but an ongoing programme of replacing old structures while making best use of new technologies. Improved insulation and energy production and management systems can further reduce the environmental footprint of the station.

Rothera is now home to marine biology, deep-field support to glaciology, geology, geophysics and survey, and is the main air facility and field work centre.

Memorials in Marguerite Bay

S.E. Black, D. Statham and G. Stride, 27 May 1958 (Horseshoe): Memorial at Rothera Point

T.J. Allen, J.F. Noel, 26 May, 1966 (Stonington); Memorial on Flagstaff Hill, Stonington Island

J.H.M Anderson and R. Atkinson, 16 May 1981 (Rothera Point): Single cross on Rothera Point

N.J. Armstrong (Canada), D.N. Fredlund (Canada), J.C. Armstrong (Canada) and E.P. Odegard (Norway), 23 Nov 1994: Memorial at Rothera Point.

K.M. Brown, 22 July 2003 (Rothera): Memorial at Rothera Point

.

References:

F. Debenham (Editor) – The Voyage of Captain Bellingshausen to the Antarctic Seas 1819 – 21

R. K. Headland – A Chronology of Antarctic Exploration

Adrien de Gerlache – Voyage of the Belgica

J. B. Charcot – Towards the South Pole aboard the Francais

J. B. Charcot Voyage of the “Why Not ?”

John Grierson Sir Hubert Wilkins – Enigma of Exploration

Lincoln Ellsworth – Beyond Horizons

John Rymill – Southern Lights

Proceedings American Philosophical Society Vol 89 No. 1 April 1945 – Reports on the Scientific Results of the United States Antarctic Service Expedition 1939-41

J. S. Pedersen and P. Curtis – The Mapping of Antarctica

D. J. H. Searle – The evolution of the map of Alexander and Charcot Islands, Antarctica.

The Geographical Journal Vol 129, Part 2 June 1963

Sara Wheeler – Terra Incognita

Jennie Darlington – My Antarctic Honeymoon

Tom Woodfield – Polar Mariner

Finn Ronne – Antarctic Conquest

Sir Vivian Fuchs – Of Ice and Men

Barbara McHugo – Topographic Survey and Mapping of BAT

Kevin Walton – Two Years in the Antarctic

Stephen Haddelsey – Operation Tabarin

And of course frequent searches on Wikipedia etc.

Richard Barrett & Steve Wormald, 2021

Memorials:-

Tom Allan & John Noel May 26th 1965 should read May 26th 1966

Terry, Will correct. Apologies.