Recruiting a Fid 1966-7 – Bill Taylor

Given that this website has been set up to collect stories and articles for Fids, family members and friends – i.e. not just those that served in the South – it may interest some site users to know more about the historical employment model, what influences motivated Fids to go South and the official recruitment process that set them on their way. While it is probably the case that the reasons for joining changed very little over the years, the recruitment process and working practices have probably moved a mile.

What follows is a snapshot of how that worked in the late 1960s …

Some Fid traditions and working practices (e.g. rum ration; “smoko” rather than tea or coffee break; weekly “scrub-out”) can be tracked back to the Royal Navy. In 1943, Operation Tabarin was a Royal Navy initiative to establish bases on the Antarctic Peninsula (at this time named “Grahamland” on British maps) to maintain Britain’s territorial claims, particularly against Argentina. Because of the expertise required to establish bases, men with polar experience were head-hunted throughout the Service, the most important being Surgeon-Commander Ted Bingham, one-time member of the very successful British Grahamland Expedition of 1934-37, which had explored large tracts of territory using dog teams backed up by a light aircraft. This meant that the style and ethos of Tabarin was essentially Royal Navy, but adapted to incorporate fieldwork and traveling practices transplanted from BGLE.

At the end of the war, the Navy handed over the Tabarin bases to the Colonial Office and a new, civilian partner – the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey (FIDS). FIDS employees soon became known as “Fids”, and under the directorship Vivian Fuchs, developed new bases and established a range of research programmes that required field work, basic exploration and topographical survey. As with BGLE, the transport supporting the fieldwork programmes was mostly dependent on dog teams that could be supported by light aircraft during the late spring and summer months. In 1962, FIDS morphed into the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) and the survey inherited all the traditions of FIDS that had developed under both FIDS and Tabarin since1943.

My BAS contract began in July 1967, having been recruited in 1966. i.e. when the Director was still Sir Vivian Fuchs, who, as an experienced Antarctic veteran, held very strong views on who would make a good Fid and how they should best be recruited. Assisted by Eric Salmon (a Fid of 4 winter’s experience), Sir Vivian shaped the recruitment process and the selection boards run by Bill Sloman, an ex-army officer and professional Personnel Officer who had been seconded from the Colonial Office in 1956. Part of Bill Sloman’s brief was to visit the major universities across the UK, giving slide lectures and explaining to qualifying graduates the opportunities for both professional experience and high adventure. He toured the universities between October and Easter before chairing the Selection Boards held during the summer, so it was Bill Sloman who was responsible for my own recruitment in 1966 – a time when the Survey only appointed men as base personnel.

What follows is an attempt to summarise my personal understanding of how BAS recruited its personnel and what Bill Sloman and his team were looking for …

New “Fids” – more correctly called “Fidlets” – were mostly recruited on what were called “2-year contracts” but were in fact contracts that would require being away from the UK for around 30 months. In the eyes of other nations that maintained Antarctic bases, these were unusual contractual arrangements, best understood in the context of the travel arrangements required to get recruits from the UK to the Falklands, then onto their allotted base. Given the ever-present threat of problems arising from the territorial dispute between Britain and Argentina, there was no air service to the Falklands and the main link to the outside world were just 10 sailings a year between Port Stanley and Montevideo, where Maclean and Stapledon acted as agents for the Survey. However, the most senior of the permanent BAS staff would sometimes fly to Punta Arenas in southern Chile, where they could be to be picked up by one of BAS’ research ships. Everyone else would make the entire journey from the UK to the Falklands and the bases on RSS Shackleton, RRS John Biscoe or the charter-vessel, Perla Dan.

To live for over 2 years, in the physical confinement of a small base without the normal amenities of western civilization is probably beyond the imagination of most people – particularly given the all-male recruitment policy – and is therefore worthy of further consideration. There were no psycho-symmetric tests, and while the Selection Board required a recruit to have the technical skills to fill the post, more than half the marks were awarded for personal qualities. In a potentially claustrophobic environment, it can be all too easy to adopt a parochial outlook and allow another individual’s personal habits to become exceedingly irritating and the recruitment process had a part to play in reducing the chance of this happening. From personal experience of wintering in Antarctica, some members of the selection board knew that what made bases run well was the fact that most recruits were highly competent, usually well-educated, shared common values, had a strong work ethic based on teamwork and understood what was required of them to make base life run smoothly. Bill Sloman’s team, after 20 years’ experience, had refined the process to a fine art, and my personal experience was that the common ground between base members and above all, their commitment to a team ethic, far outweighed the possible differences in opinion and everyone had to be prepared to work for the common good and maintain respect for the views of others. In this environment, the example set by the Base Commander had a major influence on base morale.

While Britain was unique in its Antarctic operations in using 2-year placements, Fuchs justified this choice on the grounds that it allowed the staggering of personnel change-overs, and the ability to pass on to new arrivals the experience and techniques of those that had already a minimum of one year’s experience, for almost everyone on base was noticeably more efficient in their second year, and it was a particularly useful system in aiding the choosing of the right Base Commander. Contrary to what one might expect, the requirement to sign up for a 2-year contract did not make the recruiting process more difficult.

As a result of this approach, British bases were expected to run on an egalitarian basis, with everyone taking a turn at doing the more menial tasks required to keep the base running efficiently. These tasks included being a “Gash-hand” (a Royal Navy term for the “dog’s body” of the day) who was responsible for general cleaning; laying the table; skivvying for the cook; washing up; keeping fire-boilers topped up and filling water tanks with snow blocks. It meant that from time to time, the most refined and well-educated scientist was confronted by the every-day reality that their research programme would grind to a halt if they did not keep the coal scuttle topped up and ensured that the crap-bucket got emptied. On Base T during the winter of 1969, it was my experience that while the Base Commander might be the Postmaster and a Magistrate, he too took his turn on Gash-duty, as well as helping with occasional, one-off, very physical tasks such as digging out 40-gallon drums of aviation fuel from beneath 10 feet of frozen snow-ice; taking his turn as relief cook and helping chop up rotting seal carcasses as dog-feed. Such was the commitment to base life and its routines, that if a job needed to be done and that fact was made known, it was not necessary for the BC to issue direct orders.

The recruitment process also had a built-in “running-in” period. UK-based training before departure, followed by the prolonged ship voyage, provided an opportunity to analyse character through experienced eyes and, where necessary, weed out any miss-fits.

In his book “Of Ice and Men”, Sir Vivian Fuchs writes:

“Despite every care in selection, in the end it is the quality of the man himself which makes him a success or failure as a Fid. They are all ordinary chaps. We do not seek, or find, supermen. To be acceptable a man must behave naturally, without affectations, he must be helpful to others and capable of self-control, and of course it is essential that he is efficient at his particular job.”

Fuchs goes on to state:

“Everyone is born with his own basic characteristics and temperament, but these are modified by his environment, and his own willingness to learn and adjust to his situations. The Antarctic demands these qualities, and though it may be a hard school, it develops self-sufficiency, self-control and a determination to succeed – all useful in the world at large.”

In these days of instant communication across the globe by telephone, social networking and e-mail, it is probably difficult for the modern generation to understand or accept the limitations that were stark and unavoidable realities half a century ago. While the Survey’s Personnel Section directed considerable resources into the difficult task of maintaining effective communication between base personnel and their family and loved ones, opportunities for an exchange of family news were very limited back in the 1960s. There were no telephone lines, no satellite phones and no internet.

All mail for the bases had to be routed through Montevideo and Stanley. In 1967, an airmail letter posted in the UK reached Montevideo in about a week, while sea mail took about a month. From Montevideo the mail was carried to Stanley in the RMS “Darwin”, which made only 10 trips each year, or by the Survey’s own vessels when they called into Montevideo on the way south. On this basis, mail could only be delivered with any certainty in the same season if it was posted in time to connect with the charter vessel “Perla Dan”, which nearly always called in at Montevideo on 22nd December. The Survey’s ships usually left Stanley for their last visit to the bases early in the New Year and any mail arriving in Stanley after that was unlikely to be delivered until the following season.

Against this background, the Survey offered facilities to families to send parcels (up to a total weight of 20lbs) in the Survey’s ships to men already on base. Families had only to get their parcels to the Crown Agents in London by a specified date, where the agent would take responsibility for crating up the parcels and getting them onto the relief ship.

There was also a “Personal Message” facility to support communication between families and base Fids across the months of the Antarctic autumn, winter and spring. It enabled a person designated by a base member as “next-of-kin” to send a 200-word message to that base member, in the form of a radio message transmitted by a BAS radio operator in Stanley. In 1967, the realities of communication were that the only effective radio link was by Morse code, although a Teleprinter link was installed at Base T during the winter of 1969. To get news travelling from the bases to families, base members would take it in turn to write a base newsletter that was transmitted as a radio message to Stanley, where it could be typed into a newsletter format and mailed.

My BAS service led me to the conclusion that my colleagues wintering in the “Great White South”, crudely fell into two, distinct categories. The first category was the “Career Scientist”, made up of those who were committed to a career in science, and whose line of research could be best pursued by studies undertaken in Antarctica. The raison d’etre of BAS – apart from “flying the flag” to uphold territorial claims – was to make it possible for these men to carry out their Antarctic research programmes, such as topographical survey, geology, geo-physics, astro-physics, zoology, botany, glaciology etc. When these men returned to the UK, they would usually spend many months (possibly years) writing up their work into an MSc or Doctorate.

The second category consisted of “Myth Men” – those who were romantics at heart and, inspired by the tales of the Heroic Era of men like Shackleton and Mawson, had gone south for a prolonged adventure, only achievable by signing their life away as a technician or as support personnel. In practical terms, these were the men that kept the base running or the field party safe, thereby making it possible for the hard-nosed Career Scientists to pursue their research programmes. A “Myth Man” might be a diesel mechanic who kept the generators running so that the base had electrical power; or a tractor mechanic that serviced and maybe even rebuilt a Muskeg Tractor in the field; or a General-Assistant Mountaineer dog-driver that could get a field party safely through heavily-glaciated mountains or across the broken ice of a fjord; or a General-Assistant boatman-diver; or a cook; a builder; an electrician; radio-operator; or a meteorologist. What they had in common is that they had gone south because they had a romantic notion or a driving ambition to be there, in order to savour the experience for its own sake. There would be no tangible, long term career outcomes. They wanted to experience for themselves a taste of the heroics experienced by the expeditions of the early 20th century the opportunity to work in an environment that was sure to provide opportunities for real adventures.

Many Fids have a quirky but interesting tale to tell as to how they came to be recruited, my own recruitment being no exception … Read on …

My earliest recollection of an awareness of Antarctica was as a ten-year-old, around late 1956 or early 1957, when Mum took me to the local cinema and where the “B” feature happened to be “Foothold in Antarctica” – this being the 21-minute documentary (still available on YouTube) recounting the setting up of Shackleton Base by the ice vessel “Theron” in 1955 as part of the British Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition. The film has a very dated commentary (“there are whales in your landing strip”) but it captured my imagination and from that point in time, I retained an awareness of Antarctica as a place for potential adventures, even though I hadn’t got a clue as to how they might be achieved.

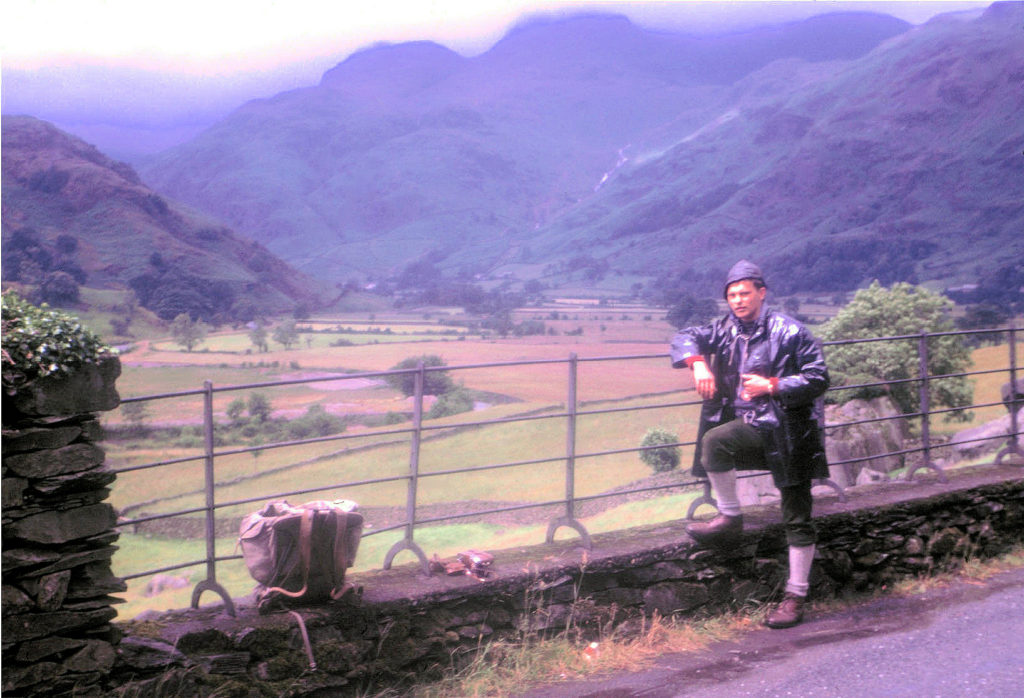

However, I was developing a taste for being in the Great Outdoors through membership of such organisations as Woodcraft Folk, Cubs and Boys’ Brigade, and by 1964, when I left home as an 18-year-old to read Law at Manchester University, I had already begun to muster a portfolio of mountain experience that included mountain walking in the Mournes, Snowdonia, Dartmoor and The Lakes. No surprise, therefore, that during my Fresher’s Week, the stall that caught my eye was MUMC – Manchester University Mountaineering Club. Joining at the same time were fellow Freshers, Denis Kinsella and Ralph Fawcett, both of whom were reading Geography and Geology and who would later be instrumental in precipitating me into contact with British Antarctic Survey.

On Wednesday afternoons, Ralph, Dennis and I would sometimes go rock climbing on the crags and quarries of the Chew Valley, following this up by an evening in the Union Bar or at one of the local pubs. One Wednesday lunchtime in the winter of 1966 when we hadn’t climbed, I saw Dennis and Ralph in the Refectory and suggested that we met for a drink that evening but was disappointed to hear that they would not be able to make it because they had already committed to attend a faculty careers lecture to be presented by British Antarctic Survey. However, they went on to suggest that I should tag along so that we could adjourn to a pub as soon as the lecture was finished. When I agreed the plan, while I didn’t know it, I had just taken one of the most important decisions of my life.

When I entered the lecture hall that evening, my expectation was to be mildly entertained and the possibility of seeking employment never entered my head.

The presentation fronted by Bill Sloman was clearly aimed at the attending science degree undergraduates, but he also explained the availability of support-personnel jobs with the survey where a science degree was not a conditional requirement. He also clarified that the personality profile of the ‘Survey’s recruits were no less important than their academic background, and the job that suddenly attracted my interest was as a “General Assistant /Dog Driver”, usually recruited for their mountaineering skills.

By this time, I had gained some experience of winter mountaineering, and as I listened to what Bill Sloman had to say, I began to wonder whether my very casual attendance at the lecture had in fact led me to a job possibility that may not have been planned but was nonetheless a job that my outdoor interests had always been preparing me for.

At the end of the presentation, I knew what I wanted to do with my life for the next few years, so hung back after the formalities had finished in order to obtain further information. Chatting with Bill Sloman about my background, he gave me some addresses of local Mancunians that had worked for the ‘Survey. If, having contacted them, I was still interested, I should write to him.

A few weeks later, to my great delight, this led to me being invited for interview at BAS Head Office in Gillingham Street, Victoria but at the end of my interview, I was devastated to hear that my mountain experience was far less than required to lead sledge parties of field scientists through heavily glaciated mountains. Then Bill produced an ace from up his sleeve – the possibility of an appointment as a Meteorological Assistant. But the offer was conditional requiring that I completed my Law degree and successfully completed the 10-week Met course that commenced in the first week of July 1967.

So it was that a week before my 21st birthday, I turned up at the Met office training school in Stanmore to begin my BAS employment – the most formative of my whole life. Thank you Bill Sloman!

Bill Taylor – Meteorologist – Signy 1968, Adelaide 1969