Why (or How) I Became a Fid

Recollections of how and why Fids Became Fids. We would welcome other contributions from Fids with interesting or crazy stories, to be added to this page.

This is a collection of stories as to why previously normal and sane people became Fids, typically involving Eric Salmon and Bill Sloman, who were well known to Fids in the 50’s, 60′ and 70’s, as the selection “committee” for new Fids.

Bill Sloman was a former Army officer, an imposing character with the obligatory handlebar ‘tache, who knew what type of man (no ladies at that time) was needed to live in close proximity with 15 to 20 other men for 24 months, including long periods at sea.

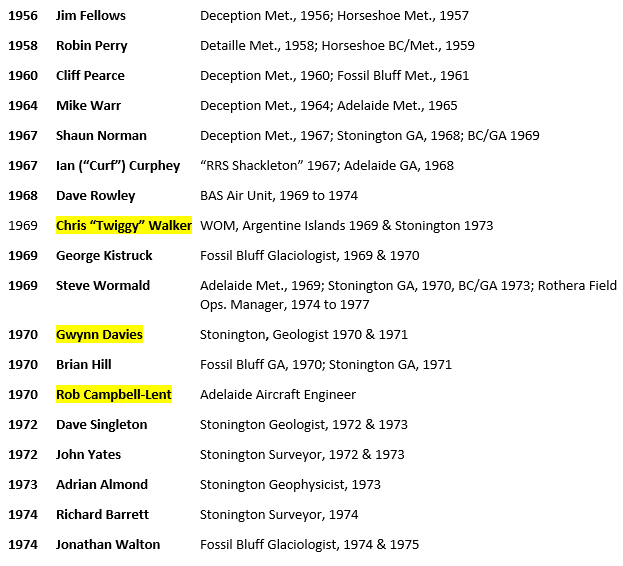

“Why I” Stories related by:

Jim Fellows – Deception Met. 1956, Horseshoe Met. 1957

At that time, I was in my mid-twenties, and as I looked around the office at the senior designers and engineers in their late forties or early fifties, some married to tracers in the office, all having a mortgage, a couple of kids, a car, all the trappings of sedate life. All already talking about their plans when they retired. I thought that that was me in 20 years’ time. The prospect of those secure but boring 20 years did not seem very inviting. I wanted some challenge in those 20 years before settling down and planning retirement, so I used to spend my spare time with my nose in the ‘Situations Vacant’ section of the Daily Telegraph. In particular, the section advertising ‘Crown Agents for the Colonies’ vacancies, which seemed to all be in exotic-sounding places like Malaya, Fiji, Aden, Palestine, Saudi Arabia and the rest. Offering a variety of work from police posts, oil prospecting to government officers.

I do not really know what I was looking for, what I expected to find, I guess it was my own form of escapism. Then one day an advert did catch my eye and a bell rang in my head. The advert ran ‘Wanted General Assistants for Antarctic Expedition. Apply Crown Agents for the Colonies, Box Number 6357’. It went on to give the full details on how and where to apply.

Robin Perry – Detaille Met. 1958; Horseshoe BC/Met. 1959 (continued)

In the summer of 1956 when I was working in the met. office at Aberdeen airport, a certain R.H. (‘Dick’) Hillson was sent for a few weeks’ further training in meteorological observing prior to going south with FIDS. I had always wondered what it was like to experience really low temperatures, I was intrigued to see the southern hemisphere night sky (although born under it in New Zealand, I had been brought back to Britain when still a baby), and the very notion of exploration was irresistible.

So when the next circular inviting applications for FIDS came round, I applied. At my interview at the Crown Agents in London, I was rather surprised to see a bloke working at a table in the corner of the room but taking no part in the proceedings. Naïvely I assumed they were short of office space!

Cliff Pearce – Deception Met. 1960; Fossil Bluff Met. 1961

Mine is a story of escape. I spent the years from five to twenty-three in the sheltered confines of the world of education at school and university, then – armed with my BA degree in geography and economics and a Diploma in education, I took up a teaching post at Stevenage in Hertfordshire. I soon realized that this was a mistake; and appalling prospect of another forty years in education opened up before me. I had to do something different.

My first escape route was to follow up an advertisement for a job in Saskatchewan – ‘No weaklings need apply’, ran the text provocatively. I was not successful. However, I soon spotted an advertisement for the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey, who were looking for meteorological assistants to man their bases in Antarctica. At that time (1959) there were eight such bases thinly distributed along the Graham Land peninsula, (now called the Antarctic Peninsula), and its off-shore islands, as well as a base at Halley Bay on the Weddell Sea coast. Between five and nineteen men wintered on each base, a total of seventy eight. This looked a really exciting opportunity to escape and, in due course, I was interviewed at the Crown Agents in London and appointed on May 5th 1959.

My headmaster was not amused and warned me of the dire consequences of losing my annual increments and of having to start my career all over again. My colleagues were much more positive – many of them already ground down by many years in the classroom. The pupils too were helpful with their knowledge and advice – ‘Mind the bears, sir,’ suggested one; ‘I saw an Eskimo on the telly last week, sir,’ offered another; ‘It’s dark there, what d’yer want to go there for?’ asked a third.

See more extracts from Cliff’s book “the Silent Sound” here

Mike Warr – Deception Met. 1964, Adelaide Met. 1965

Extracts from Mike Warr’s book “South of Sixty”, with his kind permission

Many started out their ‘career’ as a Fid in a similar manner as that which Mike Warr describes in his book, (but not all for the same reason), and below are some extracts that set the scene for the first part of the journey, to South America, before crossing to the Falkland Islands and Deception Island, and then heading south to the Antarctic Peninsula.

“Bill Sloman, the BAS personnel officer, stated I had not enough snow and ice experience to be a general assistant out in the field, and I was just twenty. Would I like to be a meteorologist instead?”

Sure!

Five references were found attesting to my ability to live at an isolated Antarctic base, though until I was there it would be difficult to prove. Then I waited, not sure of what would happen.

Despite misspelling “shop assistant” I got signed on for two years with the British Antarctic Survey; I felt better. My climbing, camping, and skiing experience had helped. Only later did I realize how lucky I had been. In 1963 less than eighty or so new personnel went south to the British Antarctic bases. How many men had not been accepted? (British women did not get to winter in the Antarctic for another thirty years).

Basic medical checks were done. Other Antarctic organizations made sure their employees had their appendixes removed. This was something the British Antarctic Survey didn’t insist on.

Shaun Norman – Deception Met. 1967; Stonington GA, 1968; GA/BC – 1969

Encouraged by Mum’s interest in the geographical world, I half lived in our local library at Upper Norwood and read all the explorers of oceans, lands, caves, peaks and ice. During the school holidays, the library also ran lecture series on intrepid journeys of exploration, often illustrated with six-inch glass lantern slides on an ancient epidiascope. It is interesting to look at those hard-won Ponting and Hurley (both early polar photographers) pictures taken with a full plate camera on a 40lb/18kg tripod. Then to compare the effort involved then, against the easy, palm of the hand, ‘point and shoot’ photography of today.

Sir Vivian Fuchs focussed my interest in Antarctica with his 1956 Trans-Antarctic Expedition and this, together with some inspiring slideshows by men just home after two years ice time must have quietly steered me southwards in thoughts and intentions.

In 1962, not yet 20, I wrote to the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) in Gillingham Street, London, SW1 to apply for a mountaineer’s job. I failed for lack of alpine experience – and failed again a second year.

In 1964, an ex-wintering man I was quizzing told me that BAS always needed – and trained – weather observers. I knew very little about weather but, determined to go south, applied as a meteorologist. At the interview I was asked the difference between cumulonimbus and stratus and, guessing wildly, probably told them about cirrus and alto-cumulus. My amused interviewers admitted that my route was the same as they – also with no weather knowledge – had taken a few years before to get in to BAS and I was promptly signed up.

Gwynn Davies, Deception Island Geologist – Summer 1968/69, Stonington Geologist – 1970 – 1971.

I was born and brought up in Denbigh, a small market town in North Wales and the seeds of my adventures started in school when my favourite subjects (and the ones l could do best) were geology and geography. We had two excellent teachers in these two subjects and a big attraction was the field trips. The first, when l was quite young, was to climb Snowdon and a large group of us were strung out on the PYG track in lousy weather. There were many other field trips to Snowdonia and the Pennines, and later a new schoolteacher, who was also a mountaineering instructor, introduced me to rock climbing, canoeing etc. I often hitchhiked to Snowdonia in the holidays to walk the various tracks or walked my dog, a Labrador, across the hills in central Wales. One summer, during school holidays, I hitchhiked to Switzerland, stayed in Youth Hostels and spent time walking above Grindelwald and Zermatt (staying in huts) which gave me my first introduction into glaciers and crevasses.

I continued with these activities at Swansea University. A few friends and I from the mountaineering club set up an exploration society and ended up organising two expeditions, one to Iran and the other to Arctic Norway (the latter with the assistance of a geology lecturer, Peter Hooper). At the time I didn’t know that Peter Hooper had been a FID, having been based in Anvers Island, but when it came time for me to decide what to do after University (I had thought of doing Voluntary Service Overseas before becoming a teacher) Peter said “have you thought about going to the Antarctic”? This seemed an interesting idea and the next thing was a trip to the BAS London office. Fortunately, I was accepted and I then joined Mike Bell and Ali Skinner as Fidlets in Birmingham University, where we spent three months studying relevant geological reports and learnt Plane Table Surveying at a local park. The crash of the Porter aircraft in 1968 caused a revision of the work program in Marguerite Bay and I went down on the R.R.S John Biscoe to Deception Island for the summer to assist the Royal Society geologists in evaluating the 1967 volcanic eruption. I returned South in 1969 to spend two years in Stonington.

George Kistruck, Glaciologist, Fossil Bluf, 1969 and 1970

How did I end up at Fossil Bluff? Well, Sir Vivian Fuchs himself arrived one day when I was at university, to give a “milk-round” recruiting lecture for BAS. I found myself thinking “Hey, I could do that. I would like that! Good fun! The sort of things that I like to do”. But apart from the film he showed I don’t remember much at all about what else was said on that occasion. It was several years later that I applied to join.

Learning the Trade

I had assumed that I would be put on to map making, which is where most civil engineers who went South ended up. I was surprised to be told by Bill Soman “with your background you could be a Glaciologist”. I managed (just!) not to blurt out ‘Oh? What’s a Glaciologist then?’ I went to Cambridge for a second interview with Charles Swithinbank and Paul Robin. They had known each other very well on an international Antarctic expedition of the early 1950’s, and they knew very well what life on a remote Antarctic outpost base was like. I was surprised by the sorts of thing that they wanted to know: not much about glaciology or surveying, or hard sums; but much more on “practical mechanics” type engineering. They were interested that I used to run old motorbikes, and could manage to keep them going. I had joined an expedition to Spitzbergen at the end of my time at university, which had involved me in lots of fiddly work keeping outboard motors going in bad conditions, coping with skis on melting glaciers, living on porridge and rehydrated food, things like that. This was interesting to them, and seemed to work for me – and I was offered the job.

I didn’t know anything much about glaciology as a subject, so I had to be trained from scratch.

I was given lots of material to read. It was like being back at University again with a director of studies, tutorials, and so on. I had the run of the library at the Scott Polar Research Institute – and that was terrific! It didn’t always have to be technical things that I read. There were hundreds of other books about exploration, about Nansen, and Arctic Canada, and so on – and I was getting paid for it! I was sent on a course in northern Sweden to learn the basic nuts and bolts of glaciology, drilling holes in ice, using dyes and that sort of thing. So I was a reasonably competent apprentice Glaciologist by the time I eventually sailed from Southampton on the six week voyage to the BAS bases. The first of these was Halley Bay, to collect glaciology equipment to bring to Marguerite Bay for the new BAS glaciology programme.

Read More about George and his Gremlins at Fossil Bluff here

Ian (“Curf”) Curphey – RRS ‘Shackleton’ and Adelaide, GA, 1969

I obtained a berth as Third Engineer on the 900 ton, 11 knot Antarctic Research Ship ‘Shackleton’, and reported for standby duties onboard ship in early August 1966 and was directed to Thornycrofts Shipyard, Southampton, where the vessel was undergoing her annual refit.

For the next 6 weeks I watched and learned as the shipyard workers thoroughly overhauled the main engine and all the auxiliary equipment. She was also hauled into dry dock for inspection below the waterline, anti-fouling, and overhaul of the variable pitch propeller. This extensive annual refit was absolutely essential, as the ‘Shackleton’ only had one engine with direct drive. While this did not cause anyone much concern at the time, we were all well aware that should we experience main engine failure into the southern oceans, our little vessel could be in dire straits, as little external assistance would be available in the remote Antarctic waters in which we would be operating. Irrespective of these sobering thoughts, I instantly felt at home in this little ship with its small engine, squeezed into a coffin-like engine room.

Towards the end of September, with the refit almost complete we went out on sea trials and swung the compass to check its accuracy. All this went well and after a few final minor tweaks we set sail for Montevideo at the beginning of October. For two days I felt as though I was at death’s door. I never really got on well with crossing the Bay of Biscay, where the long lolloping swells of the North Atlantic made our toy boat roll like a bitch. However, the eventual return of my sea legs brought with it the joys of being at sea again. In my diary I quoted Captain Scott:

‘Far better this than laying in too great a comfort at home!’

Steve Wormald – Adelaide Met. 1969; Stonington GA 1970, GA/BC 1973; Rothera Field Ops. Manager , 1974 to 1977

My Dad was a coal miner at a pit (colliery) near Barnsley, South Yorkshire. Looking back, life was pretty hard, not the least being for my Mum. My Dad spent many years, with a pit-damaged back and still working. I had managed to pass the 11+ Exam to go Grammar School, which at the time was the first step needed to go to University (although I didn’t realize that at the time), as compared to Secondary School, which invariably led to the “trades”. I passed enough “GCE’s” to move up into Sixth Form, the second step for Uni., but instead I was told to “get a job – but not in the pits”. I applied to several engineering firms, interviewed at a couple, and finally settled, at age 15, for an Apprenticeship at Brook Motors, which made industrial electric motors and control gear systems.

Being an Apprentice in Electrical and Mechanical Engineering gave me one paid day each week to attend the “Tech” – the local Barnsley College of Advanced Technology, (later, Barnsley College) on condition of attending additional courses three evenings each week, after work, to study for an ONC and HNC. This was not the easiest way to earn an engineering education, working, as I remember it, from 7:00 each morning; later in the apprenticeship, I was eventually deployed to two other factories in Honley and Huddersfield to learn different aspects of the production engineering, which entailed catching the “works” bus at 5:00am, to be there for 7:00am. And still, three evenings in school, after work.

Dave Rowley – Pilot – BAS Air Unit – 1969 to 1974

“In Awe Of FIDS” was a genuine sentiment because I could not, by any stretch of the imagination see myself sledging 4 miles, let alone 4,000! fraught with all kinds hazards and pitfalls. You guys were unique. I had 5 years of utter flying bliss, and always trying to find out what that marvellous, (not the prettiest of aircraft) the Twin Otter was capable of.

I saw the job advertised in the back pages of the Daily Telegraph in July 1969. It said that the survey were looking for a commercial pilot to ferry a Twin Otter from Toronto to Antarctica and to work in the Antarctic for the Austral summer, supplying base camps and field parties. The advert leapt out of the page. I banged off a handwritten letter , and not expecting a reply, completely forgot about it. A week later I received a reply from BAS, Gillingham Street inviting me for interview.

Read more about Dave here

Rob Campbell-Lent. Adelaide Base T. Aircraft Engineer – 1970-72

I am writing this story on 23 October 2021. Quite by chance, in just a few more days on 1st November, it will be exactly 51-years since I first flew from London Heathrow to Canada with pilots Dave Rowley and Bert Conchie and engineer Dave Brown, to begin my Antarctic experience with BAS. On arrival at the De Havilland aircraft factory in Downsview, Toronto, I started my engineer’s training courses on the Twin Otter and Turbo Beaver, before the ferry flight South from Toronto to Base T, Adelaide Island.

In early 1970 I was 21-years old, locked into a 9-year term in the British Army as an aircraft technician in the REME, with another 5-years to run before I could get out into the big wide world, and hopefully find the same kind of aviation engineering job but with a radically different employer.

My job description and work experience at that time is documented in a paragraph of the MBW Adelaide story about the 1972 Twin Otter VP-FAP Engine Change at Fossil Bluff. So there’s no need here for repetition.

I was getting a bit discontent with my lifestyle and wanted to try something different and bit more challenging. Fortunately, I did something I had been warned never, ever, to do in the Army, and that was to volunteer for anything. I volunteered for what was called a ‘Secondment’, and filled in a lot of forms presented to me by military people who I think, were trying to hide their doubt, pity or incredulity at what I was doing.

Read more about Rob here

Brian Hill – Fossil Bluff GA 1970, Stonington GA 1971

From my earliest childhood snow, ice and mountains always had a fascination for me. I can still easily recall a black and white sketch of a trapper plodding through the deep soft snow of Labrador in some kid’s book. I would have been 6 years old when I first saw the documentary film of the “Conquest of Everest” and who knows when I first saw “Scott of the Antarctic”. Both films left lasting impressions.

I was born in Glasgow although I was brought up in the small community of Linlithgow Bridge, in the Forth Clyde valley of lowland Scotland about 20 miles west of Edinburgh. My folks loved the Highlands and I can remember when Dad got his first car, a green Ford Anglia, and most Easter and summer holidays saw this wee car struggling up the valleys to the hills. I have many memories of the sound of the windshield wipers shedding sheets of rain off the glass while I struggled to peer out at the looming ominous mountains. The Torridon and Cuillin mountains in particular left me with a sense of awe and I often wondered what it would be like to climb them.

Years later, at secondary school while the smarter ones were getting ready to take their “O” Levels we were shipped off to Glenmore Lodge in the Cairngorms in the hope we might learn something there. It was all great fun and we were introduced to the various crafts of orienteering, hillwalking, canoeing, first aid, and rock-climbing, which I fell in love with right away.

Read more about Brian here

Why (or How) I Became a Fid – the 2 Shortest BAS Interviews Ever – John Yates

“I was bitten by a dog when I was very young , so I’ve never been very fond of them……….” I desperately tried to suck the words back in before they could reach the interview panels ears. I failed, I just wanted to stand up and leave. I needn’t have worried I was soon sent on my way with a doleful ”We will be in touch”. It was spring 1968 just as I was finishing my Civ Eng degree at Salford Uni. My course had included one year working on site, full-time surveying, constructing a new cement works near Ipswich and the new Coast Road between Newcastle and Tynemouth. I knew I didn’t want to be a civil engineer. I wanted to be an Antarctic surveyor and I’d just blown the only job I had applied for.

Read more about John here….

Adrian Almond – Stonington Geophysicist, 1973

Like most of the big changes in my life it happened by accident; serendipity combined with an “it seemed like a good idea at the time” attitude to decision making have ruled my life, and probably still do… but I will not know for sure until the next occasion.

I was, in 1970 and ’71, studying Earth Sciences and Physics at Leeds University. One day I saw a notice, probably in the union, probably in the bar; it was advertising a talk and slide-show about Antarctica by a man from The British Antarctic Survey, in the Civil Engineering Dept. some evening of the week. ” That sounds interesting” thinks I but only because it was an extraordinary place which had impinged upon my interest in 1958 or ’59 when I went, with my family, to see the exhibition about the Trans-Antarctic Expedition, complete with Snowcat, bright orange, parked on the museum forecourt; it had largely receded to a corner somewhere in the memory replaced by more immediate things: beer, travel round Europe, beer, pot-holing, beer, girls…. I was, in ’71, completely unaware of the existence of BAS. Later that week, I went along.

Read more about Adrian here

Chris “Twiggy” Walker – Radio Operator – Argentine Islands 1969, Stonington 1973

I was born in Poole Dorset and went to Poole Grammar School. I read all the usual stories of Antarctic and Arctic exploration while at school but always thought they were inaccessible places to me. I was in the Sea Scouts and obtained the Queen’s Scout award and also the Duke of Edinburgh’s Gold award through the Scouts.

I left school and was accepted for a two year course in Marine Radio and Radar in Southampton to gain the qualification to be a Radio Officer in the Merchant Navy. I went to work for Marconi Marine and was sent to join a banana boat called Changuinola in Southampton Docks. While waiting to sail to Jamaica we were berthed next to a little red ship – the John Biscoe – which I was told was going to the Antarctic. This was the first time I had heard of B.A.S.. I thought I wouldn’t mind some of that so I wrote to B.A.S.. About a month late I received a reply while we berthed in New York (all the American refrigerated ships had been sent to Vietnam with ice cream and supplies for the American forces so we were drafted onto the American coast instead of coming back to the U.K. from Jamaica). I was asked if I would go South straight away but unfortunately I couldn’t get off the ship until it docked in the U.K. so I had to say no for that year. I arrived back in Southampton in July the following year and left the Changuinola.

Two weeks later I went to Gillingham Street for an interview with Bill Sloman. It wasn’t really an interview at all, he just told me about the job I would be expected to do at Argentine Islands. I came out thinking “Bloody Hell they must be hard up for Radio Operators”. I then had my medical immediately afterwards. The doctor told me I had a good pair of athletes legs and if I died in the Antarctic could he have them !

So I went to Cambridge in September. This was the first time I had met a FID, everybody else seemed to know each other, where they were going and what they were going to do. I didn’t know anything ! I then did a couple of courses, one at Racal in Reading about the new radio equipment being installed at Argentine Islands and the other bases and one at Creeds in Brighton covering the teleprinters.

I had my appendix out at the beginning of November and at the end of November I went to Buckingham Palace to receive the Duke of Edinburgh’s Gold award from Prince Philip. He seemed pretty bored with it until I went up and he asked me what I was doing. I said I was going to Argentine Islands with B.A.S. and he immediately became quite animated and said “I’ve been there” and so we chatted for a bit. Afterwards several people asked what we talked about as he didn’t chat to anybody else for long. Two weeks later I sailed on the Perla Dan and so became a FID.

How I became Twiggy?

There were 12 of us at Argentine Island in 1969. We had two Robins, two Alans, two Brians and three Dicks. It was suggested some of us needed a nickname. As I was quite thin and the model Twiggy was a real super star at this time I was called Twiggy and the name seems to have stuck in FID’s circles.

Dave Singleton – Stonington Geologist, 1972 & 1973

Why did I become a FID? Well, it’s complicated! The reasons why FIDs go south seem generally linked to interests in outdoor activity, mountaineering or perhaps books they have read on Polar exploration. For me, there was some of that; it certainly wasn’t just for the geology. In fact, it was a lot to do with escaping from the family turmoil.

Unfortunately in my early teens it became clear that my parents were never going to get on. Life up to that point seemed to career from one argument to another, dad’s affairs, the odd separation when I ended up at another school for less than a week, and finally – the divorce. No surprise then that this was about the time I started to develop my independence, something that set me on the road to Antarctica although at the time I didn’t realise.

Read more about Dave here

Richard Barrett – Surveyor Stonington 1974, Adelaide 1975

In the Autumn of 1957 I was in Miss Skelton’s Class 4 at Teynham Primary School in the County of Kent, and it is only as I write this it had occurred to me to wonder if she had an Antarctic connection because she was very keen on the subject. We had a poster on the wall, possibly from a national newspaper, showing the TAE route and every Monday morning we marked up Fuch’s position on his journey across the continent. Not much happened in that Autumn term, weeks went past and it was difficult to see any progress at all and many in the class lost interest. When we returned after Christmas it was a bit of a surprise to see Hillary at the Pole, but we ignored that and eventually Fuchs reached the Pole, crossed the plateau and descended the Skelton Glacier to Scott Base. A few years later when I was given the book of the crossing I learnt that out in front of the Snocats leading the way was a surveyor with a dog team and I knew that’s what I wanted to do. Thank you Ken Blaiklock.

When I told my school careers advisor that I wanted to be a LandSurveyor, we checked it out and there were only two courses approved by the RICS one in Kuala Lumpur and the other in Walthamstow and I wasn’t allowed to go to KL. At Walthamstow I found on the staff Pete Forster and Mike Fielding both ex-Stonington surveyors who further inspired me. At college I spent way too much time caving which apart from caving all over the UK included expeditions to County Clare and Arctic Norway. How much I stressed that “Arctic” bit in my application to BAS.

I have no recollection of my interview at 30 Gillingham Street, only my medical in Stag Place. The doctor, who retired that year, met you in reception then took the stairs two at a time up to his office on the fourth floor, – if you kept up with him I think you passed. I must have impressed at the interview for unknown to me the other candidate for the survey post that year was Jon Walton and thankfully he was lured away to glaciology, thank you Dr Swithinbank, and so I was on my way to Stonington and the Terrors.

Jonathan Walton – Fossil Bluff Glaciologist – 1974 & 1975 (& Rothera Surveyor)

As the son of an early FID, many of my friends and colleagues assume that this was an ambition of mine probably before I even entered this world in 1950 in the house at the end of the platform of Eskdale Green station. Dad (Kevin Walton) was at the time one of the first 3 instructors employed by Outward Bound for their “Course No1”. However, this assumption is far from true.

However, I did grow up in a house with a pet husky and many visitors to our home had Antarctic connections. One of these visitors was Launcelot Fleming, geologist and Chaplain with BGLE who was my Godfather and after whom I was named (the “L” in J L Walton). Dad wrote “Two years in the Antarctic” when I was 4 years old and as soon as I was able to I read it of course. I used to attend some of the lectures he gave and I became a not very proficient projector operator for which I used to get paid two shillings! We had an adventurous upbringing, moving house every few years as Dad had a restless spirit – and Mum (I assume willingly) put up with it.

However, I really knew very little about Dad’s Antarctic involvement until much later, apart from what I read in his book. I certainly had no overriding passion to go to the Antarctic – that was what my Dad had done after the war, it had been a Naval operation and was done and dusted. I knew nothing of the continuation of FIDS and then BAS.

Read more about Jonathan here