Why I became a Fid – Ian Curphey (continued)

(All photos by Ian Curphey)

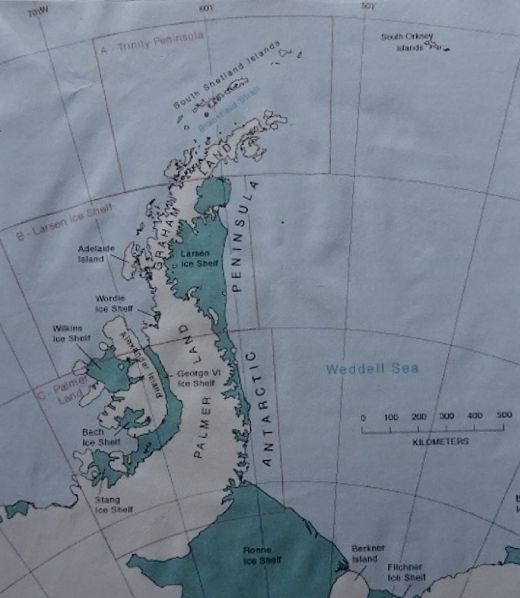

The RRS ‘Shackleton’ was the smaller and oldest of the ships operated by the British Antarctic Survey. The sister ship RRS ‘John Biscoe’ had the benefit of twin diesel-electric main engines, was larger and a bit more robust. The purpose of both vessels was to support the scientific work being carried out in various disciplines at the several British bases on the Grahamland Peninsula and to carry out oceanographic work independently, or in conjunction with the Royal Navy’s Antarctic Patrol Vessel, HMS ‘Protector’. The annual voyage of each ship lasted 6 or 7 months during which time the bases would be relieved and resupplied with essential stores and summertime building projects and maintenance carried out. The ‘Shackleton’ had accommodation for about forty passengers bound for the bases, in addition to the ships complement. The ships hold was packed to the gunnels with base food, dog food, spare parts, general stores, in fact all that was essential to ensure each base could operate successfully for the coming year. The scientific and support staff for the bases were all employed by the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) but tradition demanded that they were collectively referred to as ‘FIDS’, this being the acronym for the organisation that established the bases shortly after the Second World War – The Falkland Islands Dependency Survey. A disrespectful interpretation of this historical acronym was ‘Fucking Idiots Down South’.

The ship’s complement consisted of British Officers and mainly Falkland Islands crew as the ship was registered in Port Stanley, the seamen of those remote islands were born and bred Southern Ocean sailors, many of them having had experience on the whale catchers and at the whaling stations in South Georgia. From my perspective this arrangement could hardly have been better.

Easily settling into life at sea again we slowly edged our way south and west. We were bound for Montevideo in Uruguay where we would acquire bunkers for our Southern Oceans work. At our snail like pace of 11 knots we were at sea for 24 days. We arrived in mid November.

The voyage was without incident but made more interesting because of the diverse backgrounds of our FIDS. Many were kindred spirits in that they were climbers and mountain men. This did not surprise me, as anyone who would sign on to work in Antarctica for 2 years is highly likely to be keen on the outdoors. Talking with the likes of Georgie McCloud about his Scottish and Norwegian ski trips and Joe Porter’s exciting tales of man hauling for months in Spitsbergen and of his epics exploring underground Britain made me feel in good company.

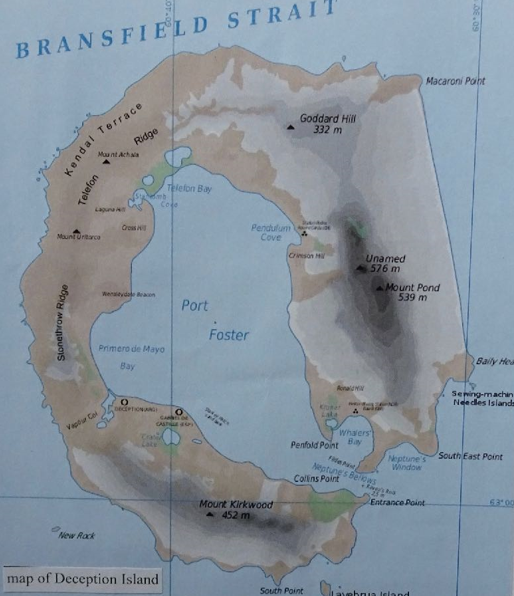

We rolled past Madeira, its high volcanic peak dominating the horizon and onward past the Canary Islands, the heat increasing by the day. The engine room temperature was well up into the high 40’s C and, when the electric deck-head fan in my cabin gave up the ghost, I rapidly made myself a hammock and slinging it under one of the lifeboats I upgraded myself to ‘Deck Passenger’. And so the days slipped astern, with little to break the routine of two watches down in the engine room, sleep when one could, fine food and very congenial company. Eventually we closed the South American coast, sighting Fernando de Noronha Brazil, and with the heat of the tropics now behind us, we arrived in Montevideo, where we anchored for the night to await clearances from the authorities. We finally tied up and started taking on bunkers on 28th October. We also received a signal that an Argentinean FID over wintering at their base on Deception Island was seriously ill and we were instructed to go on a mercy mission to collect him in the hope that we could get him to hospital in Punta Arenas, Chile before his perforated duodenal ulcer proved fatal. We departed for Deception the next day and after a very brief 1 hour halt in Port Stanley, we made all speed for Deception. Unfortunately we sailed into a fearsome Force 11 storm and had to hove to as further progress was impossible. It raged for a couple of days, seriously reducing our chances of success in saving the sick man’s life.

From my diary:-

‘I would not have thought that this little vessel could stand up to the tremendous seas that we are at present encountering. The wind is gusting 70 knots and a maelstrom of massive waves completely engulf the fo’c’sle head, sweep the length of the decks sending green water up and over the bridge. I cannot imagine what it must have been like facing such seas in ships like the ‘Terra Nova’ or ‘Discovery’. It’s epic, absolutely epic. It is almost impossible to keep one’s feet as the ship rolls violently one way and then another. We are, of necessity hove to with our nose just pointed off wind a few degrees. We are barely making any way at all, not more than two knots. This is seafaring in the old tradition’.

Eventually, the gale abated and we made some progress. However, with it being so early in the season we encountered thick but broken ice. As a newcomer into this realm of the frozen sea I was impressed. Great tabular lumps of blue-green sea ice floating in an ocean of slush and smaller chunks of ice (bergy bits). Already the paint was being rubbed off the hull and we can see great red-smeared lumps of ice drifting astern. We were forced to slow down again to a couple of knots and even at this speed the ship was being thrust about by the sheer weight of the ice. Amongst the pack ice wildlife abounds. Penguins and seals on the floes and Albatross and Giant Petrels wheeling in our wake. It was all very beautiful but not helpful to our immediate purpose of making all speed to Deception Island.

Our mercy mission was further delayed by a mechanical problem. Much noise and the engine room full of smoke. ‘All hands below’ where we discovered that a load of ice had blocked the main engine lubricating oil breather, causing the engine to overheat. We were beset by ice while fixing it but in the morning things improved. Sight of the 4,000 foot mountains of the South Shetlands harbingered good news. We were not far from Deception Island, where we arrived and dropped anchor later that day.

Word of our arrival was sent to the Argentinean base and at about 8 pm the sledge bearing the sick man arrived at the British base. We embarked our casualty and set off out to sea. Sadly, as we left the confines of the Neptune’s Bellows, the entrance to the caldera that is Deception Island, we once more encountered heavy ice and had to stop. It was unnerving sitting in my cabin watching the ice rising and falling past my waterline porthole, as the ship rolled against tabular chunks, and bits of floe scraped past the hull. As we had to maintain readiness, I could not turn in until 4 am in case the engine was required. It took us almost five days to get across Drake’s Passage, where we discharged our casualty and immediately set sail for our first proper visit to the Falkland Islands, whereupon we arrived after an easy passage on the 14th November. (We learned later that the casualty survived his long ordeal).

Port Stanley is a free port, so there was much excitement, especially amongst the FIDS. Not only would they be kitted out with all their Polar clothing, specialist footwear etc for their two year stay, but they could also purchase a selection of the very best cameras in the world and endless miles of colour film at duty free prices, less than half the cost at home. So impoverished Britishers went ashore and seemingly filthy rich Texas tourists returned, bristling with Nikons, Canons, and Hasselblads!

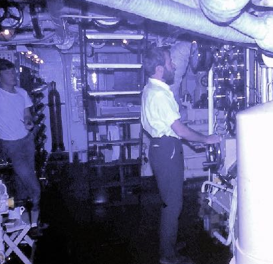

Life was a bit more structured for ships engineers. We had much to do. In order to ensure that our engine and ancillary equipment remained in top condition we had masses of preventative maintenance to attend to. It took us 12 hours to change all the main engine exhaust and inlet valves, and remove all the diesel injectors and replace them with a set that had been serviced and fully tested.

As Third Engineer, it was one of my tasks to take on water and bunkers for the next leg of our voyage, so I spent another half day making sure everything was ship shape and Bristol fashion with regard to these crucial requirements. However, I did eventually manage to get ashore, being desperate to get out on the hill, much needed after so much time at sea. I set off and climbed Mount William and Goat Ridge just outwith Port Stanley, an enjoyable 14 or 15 mile hike.

The next stage of our voyage to South Georgia crossed a notoriously stormy bit of the Southern Ocean. The island is situated due east of Cape Horn, and the seas that batter their way through this infamous gap between South America and Grahamland seem to carry on relentlessly and viciously towards South Georgia. Worsley’s account of Shackleton’s Boat Journey from Elephant Island is arguably the definitive account of sailing in these peevish and vindictive waters. From my diary:-

‘The seas build up slowly at first, a gentle cradling effect encompasses the ship. The wind freshens and starts to howl and eventually it is difficult to stand. Even putting on your trousers and socks becomes more of a fight than a function. You try to balance on one leg and CRASH! You go careering across the cabin, only to fetch up with a sickening thud as you hit the bulkhead.

Walking along the alleyway from cabin to companionway consists of bouncing from one side of the engine room casing to the other until you manage to reach the door which you have to wait to open until you get a favourable roll. Passing through requires good judgment. Any error will elicit a long cry of ‘bastard!’

After being on the ‘Shackleton’ around the Horn and in these Southern Oceans it’s impossible to imagine being seasick again. Our poor ship seems to spend much of its time burying its nose into 60 foot waves.

Sleeping is a problem. Despite packing up the outboard side of the mattress with a pillow and life jacket, to make a sort of ‘Vee’ with the mattress and the bulkhead to prevent being thrown out of the bunk, you lie awake just sliding up and down, down and up always conscious of the bedclothes pulling tight against the skin and dragging one’s body hair in the wrong direction. Such is seafaring in southern waters.’

Our stay in Grytviken in South Georgia was quite limited as our main task was to put Georgie McCloud and Joe Porter ashore with a survey party. We maintained watches as we were at anchor, but when I came off duty at 4 am, I managed to get a run ashore with two FIDS with similar ambitions. We climbed up from the whaling station and up on to the ridge to the West of Mt Hodges in the hope we might see Mount Paget and Mount Sugartop, South Georgia’s most famous mountains.

We plodded up steep snow slopes towards a rising sun and by 6 am were on the ridge with the sunshine lighting up the most spectacular views of the impressive inland peaks. It was good to be amongst ‘proper’ mountains again.

We returned to Port Stanley for orders and en-route I checked the power output of each cylinder of the main engine by making ‘indicator cards’ of the pressure during the piston stroke. By measuring the area of these cards with a planimeter it was possible to ascertain the power being provided by each cylinder. More importantly in my view, these tests would also provide a good indicator of any potential engine problem. As only one cylinder was slightly down and collectively we were generating more than 1000 HP, I felt reassured. We took our job of keeping the old ‘Shackleton’ up to the mark very seriously. We looked after her and she looked after us. I always felt we got the best of the bargain.

It’s true to say that all who sailed in the ‘Shackleton’ took her to heart and I’m sure we all shared a sense of privilege that we were part of her crew. The ship deserved a good crew and she had one. Personally, I found the company of FIDS with their diverse backgrounds and the friendliness and cheerfulness of the Falkland Islands crew much to my liking. I was truly delighted when we reached Port Stanley, that I could accept the invitation of the Peck brothers, Howard (fireman) and Robbie (Bosun’s Mate), to go out with them to the family sheep farm out in the ‘camp’ at Port Louis. We made this journey of some 22 miles over roadless, trackless country on a pair of old British motorbikes, with me adding ballast to the back of Howard’s 350 AJS. After some 3 hours we reached the station where I was made most welcome by their mum and dad. Not surprisingly, we had mutton for tea.

The next day, having borrowed the Peck’s Series 1 Land Rover, we took a tour of the sheep farm, including the shearing shed, where Howard and Robbie demonstrated that shearing sheep and not working on the Shackleton was their real ‘day job’.

We were up and away at 0430 in order to get back to the ship in time for sailing. We had trouble with the bikes as Robbie got a puncture in a boulder field. Howard ran me in and then went back for Robbie. By the time we all got back to the jetty, the ship had slipped her lines and was moving off, but we managed to scramble over the bulwark, much to the amusement of ‘Frosty’, the skipper.

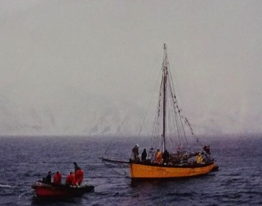

During the next couple of weeks we were engaged in shuttle work between Deception and Punta Arenas, moving people going north and home, and picking up others who had flown down to join the survey. In early December, while en-route for Punta Arenas, we slowed down to take a look at a Bristol Channel pilot cutter, on her way south. With binoculars I saw her name was ‘MISCHIEF’ out of Barmouth. I was to discover more of this incredible little boat later.

By mid December, after weathering another force 11 storm and being unable to get to Signy Island due to the pack ice we started to do some single ship magnetic survey work. This entailed towing a magnetometer well astern of the ship and cruising in a series of parallel lines over a delineated section of the ocean. This work was quite weather dependent because unless we could fix the ship’s position accurately, there was no way of knowing exactly where our readings were being taken. Relatively calm seas and sun sights were essential for this as GPS was still a futuristic dream.

We plodded along, working when we could, steadily plotting the varying magnetic fields with a 3 mile grid pattern over the South Shetland/Signy Island seas. Towards Christmas 1966, the weather deteriorated into another storm so we scurried for shelter and anchored in Potter’s Cove on King George Island, South Shetlands.

I awoke on Christmas Eve to find a holiday spirit had descended on the ship. The weather wasn’t too good but I went ashore and visited the abandoned Chilean Hut and attempted to ascend a glacier with a couple of fellow enthusiasts. We had to turn back after a couple of hours, as the visibility was so poor we couldn’t see where the crevasses were. Fortunately the weather cleared in the afternoon and we managed to climb one of the Three Brothers peaks via a steep snowfield.

On Christmas Day, the holiday spirit persisted. The ‘John Biscoe’ arrived for a joint celebration and after enjoying a morning’s skiing we returned to the ship to find we had been boarded by the crew of the ‘Biscoe’ and party time was in full swing. Our sister ships crew had brought two guests with them to ‘act as waiters’ they said. They had caught two chinstrap penguins, painted black bowties on them and they were wandering about trying to make sense of the antics of dozens of inebriated FIDS and ship’s crew.

On Boxing Day, after going ashore to repair some damage to the old base huts, we left Potter’s Cove and headed for Deception Island hopeful that our passage wouldn’t be blocked by ice. We were lucky and once inside Neptune’s Bellows we discovered that the yacht ‘Mischief’ which we had seen in the Drakes Passage near Cape Horn, was adrift in the bay. The weather was poor so we launched the ‘Quest’, our work boat, and went out and towed her in, berthing her alongside the ‘Shackleton’.

Now, here I was, face to face with a real explorer in the style of Shackleton or Nansen. One of Britain’s most famous mountain explorers, who with Eric Shipton, had ascended Nanda Devi, opened up vast areas of the Indian Himalayas and even led a British attempt on Mount Everest. Truly a man to be in awe of and admired. When we met him on 27th December 1996 he was 68 years old and had just spent a year skippering his 13.7 ton 1906 Bristol Channel pilot cutter from Barmouth, on the west coast of Wales all the way down to Antarctica. Later, in conversation with him, I learnt that his objective was to land on Smith Island, and climb the beautiful mountain that dominated this remote spot.

the old sod didn’t tell me how far south!”

The tale of this epic trip is well told by Tilman himself in his book ‘Mischief Among the Penguins’ but it is worth recording a few personal impressions of a wonderful chance meeting with this amazing man. En-route south he had lost a man overboard at night and they had been unable to find him. As a result of this he had taken on a Canadian hand, ‘Mike’, in South America. When I met Mike at Deception, he was wearing cowboy boots, a pair of jeans, and a thick woolly jumper that Tilman had given him. When I asked him about his clothing he said that he was wearing more or less all that he had. “When I signed on Tilman told me the ‘Mischief’ was on a south sea cruise.” He paused at this point and then added “The old sod didn’t tell me how bloody far south though!”

Onboard the Mischief things were pretty basic, though Tilman argued “They had a frugal sufficiency!” Food was short, mostly double baked bread, and bully beef. They cooked on a gimbal mounted primus. The small heating stove they had was unusable as the flue pipe was badly damaged (I managed to repair this for them before we left – but unbelievably I was severely castigated for this, for reasons I will explain). They had no radio or life jackets. This truly was ‘Expedition’ sailing. The privations they were experiencing reminded me of being underground in the Berger at the more difficult times.

Mike had gone up to the British base and asked the base leader if they could spare any food. They were refused and generally made to feel that they had no right to be there. I told Mike that in the past earlier occupants of the base used to store food in the old whale oil tanks as a backup in case the base caught fire. This emergency food was long since abandoned as a separate refuge building was now available, fitted out with emergency food and equipment in case of mishap. The old tinned food in the oil tanks was years old and forgotten by the current FIDS. When this ‘looting’ (the official word not mine) was discovered, it was announced that we, as employees of BAS should not give any support to ‘unauthorised’ persons’ visiting BAS bases. The reasoning was that to do so might encourage other independent parties to come south, secure in the knowledge that should they get overtaken by adverse events, BAS would bail them out.

While it could be adequately argued that their expedition was indeed ill equipped for Antarctic conditions, I contended and still contend that the spirit of Tilman and his men was to be much admired and his trip was in keeping with the best traditions of polar exploration. I could not envisage someone like ‘Shackleton’ taking that line with Tilman. I wrote in my diary at the time.

‘The same thing always happens when worthwhile activities get overwhelmed by organisations. They disregard the spirit of it and abandon common humanity’.

As a footnote to this rather uncharitable incident, I learnt later on another visit to Deception, that following an inspection by Sir Vivian Fuchs, the then Director of BAS, all the food in the whale oil tanks that hadn’t been ‘looted’ had been removed and destroyed (NOT used). It annoys me to this day that BAS, having been so mean spirited to Tilman’s hungry crew could then, almost peevishly destroy enough food to have resupplied 10 vessels the size of the noble ‘Mischief’.

We left Deception on 29th December bound for Port Lockroy. In the Ward Room that night I was admonished for assisting Tilman and his crew and I confess to feeling some loss of respect for my fellow officers. Perhaps I’m more of a mountain man than I ever was a ship’s officer.

With the year almost at its close, I was glad to be going south at last and within a day we were swinging at anchor at Port Lockroy. A truly stunning place under the shadow of great snow covered peaks. With the dawn we continued south, pushing our way slowly through heavy brash ice in the Numeyer Channel, and thence down the Lemaire Channel, arguably one of the most scenic places on the peninsula. En-route we marvelled at the towering perfectly pointed peaks which FIDS has respectfully christened ‘Una’s Tits’ after a well endowed young woman who worked in BAS’s Port Stanley office. To this day, I remain unaware of the official name of these marvellous mountains. In wonderful and most welcome sunshine we arrived at Base ‘F’ Argentine Islands. This gem of a place, initially chosen by the members of the 1930’s British Grahamland Expedition was a perfect site for a base, being sheltered and affording good access to the impressive Grahamland peaks off the mainland.

New Year’s Eve found me out of the sea ice, close to the base enjoying the last day of the year in a manner I could have hardly expected. At this time the year before I was up the Persian Gulf sweating it out, in the 45˚C temperatures of Khorramshahr, of which it was accurately stated that ‘The Persian Gulf is the arsehole of the world and Khorramshahr is ten miles up it!’ Reflecting on this made me appreciate my current position all the more.

We remained in this wonderful place, discharging cargo and swapping old FIDS for new and headed north by the same route, through the Lemaire and Numeyer. I was fortunate to be on deck as we passed the magnificent Mount Francis, rising straight out of the ice strewn sea for almost 9,000 feet. We headed for Drake’s Passage bound for Punta Arenas to disembark the homeward bound FIDS who had opted to travel the length of the Americas overland, to ease themselves into returning to a life in slightly less adventurous Britain.

In order not to infer that wandering about in Antarctica is all beer and skittles, disagreements and minor resentments did occur. Perhaps this sort of thing is inevitable when people of diverse backgrounds are thrust together in the confines of such a small place as the ‘Shackleton’. I have already mentioned that my personal feelings towards some of my fellow officers had taken a bit of a dive following BAS’s official treatment of Tilman and the crew of the ‘Mischief’ and an extract from my diary in early January 1967 illustrates that darker thoughts occurred at times:-

‘I realise that one shouldn’t put down one’s innermost thoughts with regards to fellow crew members as one’s opinions change regularly depending on one’s mood. However, just now ‘Fuzzy John’ (Second Engineer, an enormous man with a large ginger beard) revolts me. His cabin stinks to high heaven, as most of the time he is off duty he just lies in his bunk belching and farting and generally giving the impression of an overgrown lout with little concern for others. Although our ventilation in the engineers accommodation is poor, as it is situated on the waterline with no possibility of opening a porthole, he makes things almost unbearable as he keeps his cabin radiator on full blast. This ‘enhances’ his aromatic fragrance of farts, dirty socks, and filthy underwear. He’s a dirty smelly git. I’d tell him all this but I suspect it would probably cause unpleasantness.”

We spent 3 days in Punta Arenas, where I had a night ashore with a bunch of returning FIDS. It’s a wild west town ‘Punta’ and I suppose it was inevitable that we would end up in a dive like ‘Maria Theresa’s’, one of the many bordellos which pass for bars here. Sleazy indeed but definitely not a place one would forget. One well known whore came and sat at our table, pulled out a battered tit for inspection and requested to all “You, me, fucky fucky”. There were no takers, despite the advanced state of drunkenness. Finally, she left in disgust when a well oiled FID offered her the 48 centesimo’s (about 1.5 d) that was lying unwanted on the table.

It was well known amongst the Antarctic ships, operating down south this year, that following shore leave being granted to the crew of HMS ‘Protector’ in Punta Arenas just before Christmas, more than thirty men had contracted what was euphemistically called ‘Punta Knob’. The general refusal to participate in any of the ‘joys’ offered was hardly surprising.

We returned southwards, passing Statton Island, south of Cape Horn on 11th January and headed for Deception Island, where I managed to get ashore. We often took on fresh water here as there was a natural spring close to the shore and the fact that the harbour was simply the inside of a supposedly extinct volcanic crater with scoria beaches, it was possible to drop anchor close in and reverse the ship shoreward until her stern dug into the beach. We then ran a pipe from the ship to the spring, connected a small petrol powered pump and filled up our water tanks.

Once ashore, I was watching the base FIDS moving and stowing the cargo which we were discharging and as one of the snow tractors was losing steering due to the weight in the rear bucket lifting the wheels from the ground, I offered to sit on the front to act as ballast. Unfortunately the driver swung the vehicle sharply to the left and I fell off onto the caterpillar tracks. I sustained a badly sprained wrist, a bloody head, and a welt across my back that looked as though I’d been flogged before the mast. It was a bit ironic really; there were only three vehicles within hundreds of miles and I got twatted by one. The next day I was sore all over. My shipmates insisted I was lucky. Frankly I saw nothing lucky in being crunched by a snow tractor.

The ship was now scheduled to commence its seismic survey program. This involved steaming in a similar 3 mile grid pattern to that used for the magnetic survey, but towing a long ‘rubber snake’, which contained a series of hydrophones. These were carefully ‘listened’ to and recorded in the bowels of the ‘Shackelton’ by a team of boffins wearing earphones, with eyes glued to a flickering oscilloscope. What they were looking and listening for was the reflected sound waves from the different strata levels of the seabed when we exploded 25 lb or 50 lb charges of TNT tossed over the stern of the ‘Shackleton’. These were fired by a plunger device held in the tremulous hands of a FID, entrusted to set off the charge, the firing mechanism and the TNT being connected by a thin bit of wire of suitable length. This system of work provided the boffins with a depth profile of the seabed and an indication of the geology of the underlying rock strata. At times this work was carried out in conjunction with HMS ‘Protector’, when she was responsible for discharging larger amounts of TNT and we merely listened. As an engine room officer, I preferred this two ship arrangement as single ship seismic work minded me too much of the WWII film ‘The Cruel Sea’.

The difficulty of carrying out this work lay primarily in the sea conditions we encountered, as heavy weather created too much background noise for the hydrophones to operate successfully. As a consequence of this, the several weeks we spent stooging around up and down the turbulent seas south and east of Cape Horn, was continuously interrupted by the ship having to cease operations and go and find shelter on the leeward side of the South Shetland or South Orkney Islands. This was a welcome relief from being remorselessly buffeted by gales and worse but not very efficient with regards to obtaining results.

On successive spells of sheltering at Signy Island I managed to make climbs of the Observatory Ridge via the ‘Khyber Pass’ and, with Jim Conroy, an interesting and steep snow and ice gully in Paal Harbour, which provided several good pitches and a cornice to be remembered for its gallant attempts to prevent our exit at the top of the climb.

Towards the end of February, we experienced a storm which was unusual in that the skies remained relatively clear. Spindrift raced from the tops of the waves and shards of ice travelled with great speed through the tremendous troughs of the heavy seas. The vast peaks of Coronation Island, festooned with plumed caps of spiralling snow, hovered over this maelstrom of a sea, under a watery sun. The ominous sky was striated with strange pencil-like strands of yellow light, ethereal and awe inspiring. The beauty of such a place at such a time, seeps into the soul. We truly are but intruders in this Antarctic world, as we search amongst the enormous icebergs and the glacier foot for somewhere to shelter from relentless wind and low driving snow. Everything changes so fast here that fine weather must be lived for the moment. We were truly amidst great things.

By early March, we escaped from playing hide and seek with the elements and headed off on another welcome foray to the south. It was good to be underway again. We steamed past the large American base at Anvers Islands which impressed us all by the amount of men and machines that we observed working cargo. Their resupply vessel was the enormous United States Coastguard ice breaker ‘Westwind’ which was some five times larger than our puny, but move loved ‘Shackleton’. We were told she could push her way through six feet of ice, due to the fact that her 10,000 HP engines could thrust the bows of the vessel up onto any floe and then by means of ‘wobbletanks’ she could be induced to rock from port to starboard rapidly, thus ‘cutting’ into the pack and carving a channel for herself. The ‘Wobble Tanks’ were fitted on either side of the vessel and sea water was pumped rapidly from tank to tank at a rate of thousands of gallons a minute to effect the wobble. Of necessity, one has to admire American technology. We eventually arrived at Base ‘T’ Adelaide Island, our first base within the Antarctic proper, as the base is sited below the Antarctic Circle.

Having finally made it south of the Antarctic Circle, I went mad and put wine on for dinner in the ward room. The season was slowly drawing to a close. The main resupply work was completed and the oceanographic programme, though not as successful as had been hoped, was now astern. We now embark on a series of last minute mop up operations prior to our departure. The sea ice further south was starting to freeze up and the prospect of getting stuck in the ice was an added incentive to be cautious.

We returned to Port Stanley as we needed to work on the main engines, in readiness for the 8,000 nautical mile return voyage. We set to as soon as we docked and once more replaced all the main engine valves and injectors and generally made good any minor defects.

All homeward bound FIDS and ships officers were required to attend the Governor of the Falkland Islands cocktail party and while events like this are not really the sort of thing the likes of me were used to, I did my best not to disgrace myself.

A friend and I managed to climb Mount Kent, a large hill, almost on the other side of East Falkland. The weather was reasonable, but at times we were glad of a compass. It was a long walk of some 25 miles which took us over ten hours, but given that this would be the last proper leg stretch before several weeks at sea, it was well worthwhile. I was stiff the next day however!

Despite the onset of winter, we had to make another visit to the Argentine Islands to rendezvous with the ‘John Biscoe’ and take some of her returning FIDS to Port Stanley. This was necessary as she had more people to pick up from the southern bases but not enough accommodation to house them unless she could offload some bodies to our vessel. En-route back to Port Stanley, from where we would finally embark for home, we made a final and enjoyable trip to Grytviken, South Georgia.

From my diary:

‘Arrived in South Georgia at noon today. What a difference the advancing season makes. The snow has almost gone. The peaks once majestically cloaked in snow with the lower reaches riven by sastrugi, are now transformed to craggy monoliths with their lower slopes covered in tussock grass and lichens of a thousand hues. Green is predominant, making the place almost seem fertile.

The air is still, and the waters around King Edward Point are limpid, like a Westmoreland lake. Gulls scream and elephant seals roar, disturbing momentarily the sense of tranquillity that is inherent in this beautiful place. Following the coast round to the derelict whaling station, forlorn and deserted now, one is reminded of older times when Grytviken was full of hard living men, who caught and processed the then abundant whales of the Southern Oceans. It’s quiet now, only the occasional bellow of a seal or the cry of a bird. Proceeding past the crumbling plan, half submerged whale catchers and rusting ironwork, gently flapping in the breeze, one follows the beach covered in rocks still greasy with blubber and littered with giant vertebrae of slaughtered leviathans. Long ago the sea ran red with the blood of the last kill, and washed gently over these shores. Up on a slight hill, almost buried in drift snow, tamped hard by the wind lies Shackleton’s lonely grave, an almost unnecessary reminder that one is indeed amongst great things’.

Back in Stanley a sort of holiday mood prevailed as everybody was aware that we were soon to be homeward bound. I made a couple of interesting trips by Zodiac prior to departure.

Being the first landfall for old sailing ships after they had weathered Cape Horn, it is unsurprising that there are literally hundreds of known wrecks around the islands shores. Many were wrecked, after being storm damaged and unable to manoeuvre away from a lee shore and several who managed to gain the sanctuary of Port Stanley’s fine harbour, were so beyond repair that they were fated never to leave the islands. There were two such ships easily accessible, still in the harbour itself and another, a truly famous ship, that lay holed and aground out with Port Stanley at Sparrow Cove.

I first visited the hulk of the sailing ship ‘Fennia’ which lay at anchor in the bay. Dismasted rounding the horn, she had made it to the Falklands under jury rig, but was too far gone to be repaired. This resulted in her living out her latter days as a wool storage hulk for the Falkland Islands Company. Eventually she leaked so badly this usage had to be abandoned. Being onboard an old ship like that brought back all the ‘Boys Own’ stories about life before the mast that one was steeped in during one’s childhood.

A more interesting, but less stable wreck, which still had all her masts aloft, was the ‘Lady Elizabeth’. She had been towed to the most distant end of Stanley’s long harbour and run aground there, in case, because of her condition she had sunk in the harbour and caused an obstruction or hazard to shipping. A fine bouncing ride in the Zodiac, when we were entertained by Commerson’s dolphins leaping in our bow wave made the visit to this old lady even more memorable.

Finally, to the most famous of the vessels that found themselves stranded here. Isambard Kingdom’s magnificent SS ‘Great Britain’ had limped into harbour, many years ago, having been hard used rounding the Horn. She too, had been used as a storage hulk, but when concerns arose about her possibly sinking in the harbour, a passing Royal Navy ship was detailed to take her out and scuttle her. Fortunately those in command knew of her history, and had instead towed her out to Sparrow Cove where they put a hole in the port side and sank her in shallow water. In the 1960’s she was still in the cove and she produced the most delicious mussels. It was in quest of a few bags of these that we ventured out of the harbour to see her. It was possible to sail inside the vessel via the small hole in her side. We dutifully scraped off enough mussels for a veritable feast. From the landward side it was possible to board her and make one’s way along her creaking decks. Her main mast was still aloft and many of her gigantic spars lay on her rotting plans amidst a tangle of old ropes and rusting steel cables. She was still a beautiful looking vessel even in her dilapidated state. A few years after my visit she was raised by a Dutch salvage company, taken by raft to South America and ultimately returned to the same dry dock in Bristol, which Brunel had had constructed in order to build her. Initially she had had six masts and a steam engine. Built of steel, and the first commercial vessel to be driven by a screw propeller she is a most important part of ship building history. Today she is a major attraction on Bristol’s waterfront, having undergone considerable restoration.

And so with many thoughts of old sailing ships, mixed up with the incredible experience of a first visit to Antarctica, the good ship ‘Shackleton’ departed for more temperate waters. We called at Montevideo, homeward bound, where I experienced being robbed under threat of violence. Fortunately it was only a camera I was relieved of and by 15th April 1967 we were truly homeward bound. We reached Southampton, without notable incident on 7th May, after a twenty-two day passage. On this first voyage to the Southern Oceans we covered in excess of 30,000 nautical miles.

THE SECOND VOYAGE

Part of the summer of 1967 was taken up with standing by the ‘Shackleton’ in Thornycroft’s Yard, ensuring that our annual refit went well. I shared this duty with the other engine room officers, which meant some six weeks duty each. The rest of the time I was on leave. This was dominated by my participation in the successful 1967 Gouffre Berger Expedition, described in some detail in the previous chapter.

I rejoined the ‘Shackleton’ for my second voyage and by the 16th October, I had recovered from my usual ‘Bay of Biscay Blues’ and walked the plates on the sea legs once more. We arrived in Port Stanley on 13th November after an uneventful crossing to Montevideo and the expected rough weather crossing over to the Falkland Islands.

From my diary:

‘We are hove to again, the weather is on the nose and already we are a day late on our ETA even from Monte! It’s impossible to get the better of these southern seas. Everything is an effort, even writing this, the difficulty being remaining seated. The seas are very steep and even at our greatly reduced speed, the pounding of the waves on our tiny vessel is impressive. Great cataracts of spume crested water cascade upon us in opalescent fury. Gargantuan waves thump against the hull and slap playfully on the thankfully very thick armour plated glass of the porthole. My cabin alternates from light to almost night-time darkness as the port vanishes and rises beneath the endless undulating of the sea. There is however, an awe inspiring beauty about it all that captures the imagination. This offsets the discomfort somewhat. One feels very close to nature in a Force II, with the waves lashing viciously on the thin steel hull.’

On our voyage down I’d made some good new friends amongst this year’s FIDS including Ian Sykes, a Lochaber climber with whom I remain close friends, some fifty years on. In the Falklands we went climbing together for the first, but not the last time. Outside Stanley we had a great day on the crags finding several grooves and slabs that were worth putting a rope on for. Later, in inclement weather, we climbed the Two Sisters Ridge, finishing up on a good slab climb of about V Diff standard. The rock was excellent, but being previously unclimbed it was well covered in lichen.

After some four days socialising in Port Stanley and carrying out all the necessary tasks of outfitting the new FIDS and reporting to Government House etc we set out on the 750 nautical mile passage down to Deception Island. As Third Engineer, I was still permanently on the ‘Death Watch’ (12 to 4) but I was blessed with a Falkland Islands fireman who used to vanish topside in the middle of the midnight watch and return with a freshly cooked penguin egg omelette for me, with a mug of tea and a couple of slabs of toast. I particularly enjoyed these when he mashed half a tin of corned beef in with the eggs. Giants would thrive on such a fine fare.

The weather was foul when we arrived, so much so that it was too dangerous to go stern to prepare for taking on water, so we spent the night swinging on the hook in the deep water of Whalers Bay.

Because of the poor holding for the anchor (volcanic ash) we remained on watches and when I went on at midnight it was still light enough to see quite clearly. The old whaling station with its shattered tanks and erratic chimneys set at weird angles amongst a sea of drifted snow. The derelict ironwork, deep brown with the rust of years and blasting winds stood stark and black against an austere backdrop of snow and the caldera rim.

The next day, the weather improved and we moved ship in order to take on water. We also commenced working cargo and although the weather deteriorated again, we managed to continue our work. In my off duty time, I went ashore to help with the cargo, as being an engineer is essentially a sedentary job and I yearned to get the old muscles working again. We remained at Deception for several days and during engine checks we discovered that one of the cylinder heads on the main engine was leaking, so a day was spent getting our spare part down from its storage place in the funnel and replacing it. A long heavy job but far better done here in a safe place than at sea. When we left for Signy Island and South Georgia we had the additional test of checking that the magnetometer was working. Given that none of the ships company particularly enjoyed cruising up and down off Cape Horn, dodging gales or worse, and never being able to sit, eat or sleep in comfort, the general wish was that it would be kaput and beyond repair. Sadly, this didn’t materialise.

Early in December, having only briefly visited Signy Island to deliver mail, we set off for South Georgia. As the FIDS who had wintered over had not received any mail for almost a year, we as the first ship down in the ice, were honour bound to act as postman and visit all the bases as soon as ice conditions permitted, hence our whistle-stop tour.

Coming off watch at 4 pm one afternoon, feeling heady and lethargic from engine fumes, I had an overwhelming desire to go topside for a breath of fresh air. I was pleased I did .

From my diary:

‘Fine views of Clarence Island, softly covered in brilliant snow. Hard rock welded beneath giant haycocks of solid ice. The whole island shimmering in the brassy glare of the sun.

The wind is reasonable with white horses dancing in the lee of the island enhancing the scene. Tilman often wrote lyrically of ‘the mountains and the sea’ and at times like this it is easy to see what he meant.

Elephant Island and Seal Island, close to hand, slink in the misty haze of the horizon. A pale blur almost without true form, but retaining the mystique and remoteness born of the part they played in Antarctic history.

Shackleton’s men must have been hard pressed on these windswept and inhospitable shores. One is very aware of this even though it’s a nice day, the temperature is just below zero.’

On 5th December we received a signal informing us that there was a general emergency on Deception Island due to the island violently erupting. We made all speed to the vicinity in case we were required. En-route we received good news regarding the safety of all the base members on the Chilean, Argentinean and the British bases. So at 1600 hours the same day, we anchored close by in Discovery Bay, Greenwich Island to await further developments.

The ‘Piloto Pardo’, the Chilean Antarctic support vessel had evacuated all the inhabitants of the three Deception bases and was currently on her way to the Chilean base, where we lay at anchor. The evacuations had been carried out using the ‘Piloto Pardo’s’ helicopter so all personal effects, scientific papers and the like had of necessity been left behind.

The decision was made that the ‘Shackleton’ would try to get into Deception Island with a view to collecting the FIDS personal gear. We learnt more of what happened from the evacuated British FIDS when the ‘Piloto Pardo’ arrived. The tales of the eruption varied but by all accounts it was quite epic. Great explosions and cascading ash. The north and northeast of the island being the main site of the disturbance. The ex-Deception FIDS were convinced that we would be able to get into the base. It occurred to me that ‘They would say that, wouldn’t they?’ FIDS cameras and photos were prized possessions.

In reality there was clearly some attendant risk, especially as the only way in and out of the lagoon-like Deception was through Neptune’s Bellows, a narrow steep sided cleft, merely a break in the volcano rim.

On 7th December we arrived at Deception.

From my diary:

‘All the islands round here, up to four miles away, are covered in ash from Deception. As we approached the island great mushrooms of ash appeared on the skyline. Clearly the island is still erupting.’

We went in through the narrows, and I was fortunate enough to join the shore party. It was important that the engine of the ‘Quest’ was kept going, hence my inclusion.

The desolation at the base was amazing, ash everywhere and still falling. All sorts of detritus lay along the beach due to the tsunami-like tides. The FIDS were soon swarming over the wrecked base getting their gear together when she blew again. Great billows of steam, ash and shit, flying thousands of feet in the air like an enormous geyser. The eruption continues at almost regular intervals. The sight was awesome – in the true sense of the word. After hurriedly collecting their treasures; the FIDS clambered aboard the ‘Quest’ and we returned to the relative safety of the ‘Shackleton’. We steamed out of Whalers Bay and out into the deeper waters of Port Foster, where we cruised about trying to get a better assessment of the situation.

It is a bit pointless trying to describe the scene as the enormous force and power of what we were witnessing is beyond words. I was completely overwhelmed by it all. I’ve not been so impressed by any natural phenomena. It was even more awe inspiring than my first sight of the giant stalagmites, the Gouffre Berger’s Hall of the Thirteen. What an experience. Ash was settling everywhere and the ships decks were covered in it. Throughout the weather remained fine. Following a particularly violent blast, ‘Frosty’ put prudence before valour and, in a strange heaving sea, we headed out from Port Foster to the safety of the open ocean.’

As we set off back to Discovery Bay, great palls of steam hung over the island. When we had first arrived here, some twelve days previous, the entire island had been plastered with snow. This winter scene had been transmogrified by falling ash. The island was now completely ‘Mordor Black’. This very dramatic interlude had a pleasant benefit, while being extremely exciting and unique in its own right, it had stolen much time off the incredibly boring and often uncomfortable magnetic survey!

The ‘Shackleton’ was now down by the gunnels with FIDS, many of whom no longer had a home to go to, so we headed north to Port Stanley. We disembarked many FIDS here, several were delighted at getting a couple of weeks holiday in the ‘flesh spots’ of the Globe and Ship Inns, but those who were destined for an early return to the UK were very disappointed. The only upside for them was the assurance that they would be guaranteed to come down again next year, should they so wish.

In mid December, the ship sailed for South Georgia, always a highlight of the trip for me, especially so this year as my new found climbing pal, Ian Sykes and I had schemes afoot to get a climb in while we were there.

From my diary:-

‘Sykes and I got up at 2 am. Just getting light. Not particularly inspiring weather, dull but clear with gentle snow drifting down. We started up behind Grytviken whaling station, and after crossing a stream we started up the screes at the foot of Mount Hodgson (1985 feet). Everything was a bit slippy due to the new snow, but after climbing a ramp we hit easier ground. We couldn’t gain access to the ridge visible from Grytviken, so traversed below a series of rock buttresses finally reaching a steep snow gully which brought us out near the top. By 4 am we were on the summit. The view was great, but the light too dull for reasonable photographs. While on the summit we re-erected a survey mast and then descended steep snow and icy rock to the bottom of our gully. We returned to the ‘Shackleton’ at 6.30 am and sailed at 7.30 am. A clandestine trip, which had I asked permission to undertake, would most certainly not have been granted.’

We both agreed it was well worth missing sleep for, and later that day, when we were hove to in a gale, just off South Georgia, I was doubly pleased that a weather window had presented itself at exactly the right time. We remained hove to, in sight of land, for the next 15 hours in a force 10.

Thanks to my friendship with Sykes, who was heading south for two years to do my dream job of driving a dog team out of Stonington, I acquired some very useful information. I had repeatedly asked BAS in Cambridge to consider me for a base job and they always prevaricated saying I was “too late for this year” etc. However, they also kept my hopes up by dangling the carrot that I would get onto a base someday. I learnt from Sykes that when he applied for a GA’s job (General Assistant/Gash Hand) there were some four hundred applicants for each position offered. In contrast to this, getting engineers for the survey ships proved very difficult, so from a BAS perspective, it was most certainly not in their interests to give a job which could be filled easily with superbly qualified climbers to a mediocre mountain man who happened to be a ship’s engineer.

Having become increasingly disgruntled over this, I decided to give my notice to leave the ‘Shackleton’ at the completion of this voyage and make a final application for a GA’s job on a sledging base. I wrote a letter to ‘Frosty’, the captain, advising him of this using some notepaper left over from the Gouffre Berger Expedition. He didn’t take my resignation very well. In fact his hands were shaking when he read the letter as though my resignation was a personal affront to him, which it most certainly was not. In his anger he castigated me for writing to him on my private expedition notepaper, saying that I shouldn’t implicate BAS in my personal ventures!

Anyway, the deed was done, and no matter what transpired, I would not be making a third trip as Third on RRS ‘Shackleton’.

In late December, we made an attempt to complete the dreaded magnetic survey, and in reasonable weather, we steamed up and down amongst the ice for some days. In reality it was pleasant enough, as we were not plagued with high seas and gales of wind.

From my diary:-

‘A beautiful sunset last night: the cloud heavy and low on the horizon. A band of clear sky, dyed pink by the departing sun, cast undertones of purple on the clouds above. The impressive outcrops of Elephant Island stood out dark and proud with the sun, like a fiery orb, dancing on the surface of the sea. As I stood and watched, the red of the sky grew darker and eventually, about 11 pm the entire horizon was on fire, as far as the eye could see, to port and starboard. It is scenes like this that make the minor privations of shipboard life worthwhile.’

As Christmas Day approached, the magnetometer was hauled aboard and we set a course for Port Stanley where we arrived on the 24th. Christmas in our home port was really appreciated by our Falkland Islands crew, and it was considerate of the BAS and in particular old ‘Frosty’, to ensure that this happened from time to time. For myself, I would rather have been at anchor off some snow covered island with a chance to go walkabout. There was a general coming together of the survey’s vessels with the ‘John Biscoe’ and the chartered ‘Perla Dan’ all being alongside for the festivities. Sadly for me, just prior to our department for Punta Arenas at year’s end, my climbing buddy, Sykes, transferred to the ‘John Biscoe’ as he’d volunteered to go for a jolly to Halley Bay, in the Weddel Sea. Our trip over to the tip of South America was short, pleasant and uneventful, and by 2nd January, we were back in Port Stanley, having spent New Year at sea.

The early part of the year was spent stooging around in the seas of the South Scotia Ridge, between the South Orkney Islands and the South Shetlands. Our oceanographic survey work following its normal pattern, of surveying whenever the sea state permitted and seeking shelter when it didn’t, in the hope that normal service could be resumed as soon as possible.

It has to be confessed that, while this work was of real interest to the scientific staff, desperate to complete the geological and magnetic maps of this obviously geophysically important area, the constant, seemingly aimless wandering about ‘twixt’ scattered islands and raging seas didn’t suit us mere sailors too well. By mid month, we had finished the last run of the Elephant Island Survey and we set off south, intent on getting down to the Argentine Islands, ice permitting. Our route, via the Bransfield Strait, took us past the remote Bridgeman island, which loomed out of the strange obscure light caused by the steady fall of almost hail-like snow. Visibility slowly coming down to less than a ship’s length. Occasionally, isolated icebergs of gargantuan proportions emerged into sight. Silent sentinels observing our tiny ship, dull red in the poor light and moving snail-like through a polka dot sea.

The following day we were off Trinity Island with Smith Island on the horizon, proud and needle sharp on the starboard bow. Through binoculars, it appeared inaccessible and my thoughts turned to Tilman and the ‘Mischief’. It seemed a formidable place for that gallant but ill equipped expedition to land let alone scale the formidable mountain that dominated its skyline. (I learnt later that ‘Mischief’ was indeed unsuccessful in her attempt to land. But far better to have tried and failed than not make a brave attempt). We continued along via the Trinity Coast finally anchoring for the night at Port Lockroy, a safer option than struggling to find our way through ice infested waters. At first light, we continued south, called briefly at Palmer, the American base on Anvers Island, before seeking to enter the Lemaire Channel. Alas, we couldn’t get in due to the ice conditions so we steamed through French Passage, this proved to be a great place for wildlife. Apart from ubiquitous Adélie and Chinstrap penguins there were a lot of seals, including crabeaters and sleek sinister leopards.

Arrival in the ‘Banana Belt’ and Base ‘F’, Argentine Islands, was joyous as usual. A perfect still evening with the surrounding peaks glowing in the low evening light. Jewels sparkling like a giant Kohinoor. We dropped anchor just before midnight.

We had the great good fortune to spend the next three days in this Antarctic paradise.

From my diary (16th January):

‘It verges on the impossible to try to put down the beauty of a day like this. Out of my bunk for breakfast, the sun beating down on brilliant snow and ice with a panorama that defies description.

I worked all morning in just trousers and wellington boots. The heat was fantastic yet the air temperate was only 2˚C.

In the evening I went skiing amidst a glorious blaze of colour. A myriad reflections of the jewel-like mountains in a crystal sea. The skiing was good, getting better as the evening wore on. When I finally came down, after traversing across the island, I was completely mesmerised by the view to the south. Against the setting sun, icebergs seemed to fill the whole ocean as far as one could see. The final run was great. The surface had hardened with the descending sun and my skis slid like butter on a hot plate. Zoom! I’m down by the ship, joining the others, who had been playing with the dogs, waiting for the ‘Quest’ to take us back to the boat. We didn’t have to wait long – a great tabular berg jammed itself between the ship and the shore, and we walked back! I’m as red as hell from the sun, but what a day this has been.’

I skied each evening for the next two days and returning a bit earlier one night, I witnessed an amusing incident. After the shore leave boat had returned, we could see a couple of FIDS doubtless well oiled after a night in the Base Bar standing on the shore. When the boat made no attempt to go and pick them up they in their wisdom decided that they would come back aboard by climbing the two stern mooring lines, which combined with the anchor kept the ‘Shackleton’ in position while she was working cargo. It is clear that they were unaware that even the largest of vessels can be moved by applying weight to a line. As they hauled themselves along the ropes, they slowly but inexorably sank into the sea. As the sea temperature hereabouts is -2˚C they swam to the shore rather rapidly. The ‘Quest’ was sent out immediately to pick them up, as wet men at zero temperatures don’t last long. They caught a bollocking from ‘Frosty’ but survived their unintended dip.

On 19th January, our wonderful summer holiday at Argentine Island ended, as we headed north for Deception Island. The pleasure continued, albeit briefly, when we discovered that the ice had gone out of the Lemaire Channel, so we took this fabulous route northwards.

Our fine passage was interrupted when fate took a hand. We sprung a leak which demanded instant repair. We headed for sheltered waters off the American Base at Anvers Island and made a preliminary survey. We had burst a sea suction pipe and water was flooding in through the hull. We set too building a cement box round the burst pipe, a difficult task. It also meant we couldn’t start the engine until the cement had set. Meantime, our venerable New Zealand captain, the iconic ‘Frosty’, increased his bank balance by selling cigarettes and booze to very eager Americans. As the difference between what he would have paid for bonded stores, sans duty, and the price that rich Americans would pay was considerable, he did quite well for himself. I have to confess to envy, I could have well have done with a boost to my own assets! During this enforced stay it was necessary to put another anchor down to keep maximum stability. This proved impossible as the starboard anchor windlass was found to be damaged. We tried to repair this but discovered that we didn’t have the facilities to do so. We managed with one anchor that night, but the following day we had jury rigged the winch to everyone’s relief.

Bad things come in threes and our cement box repair didn’t prove up to the job so we had to set to again, this time extending the concrete works to encompass the entire sea inlet strainer. This did the job, but the work cost us another day’s delay.

I took advantage of this by visiting Palmer Station Base which was in marked contrast to our own ‘scout hut’ type establishments. There were massive building projects going on. Bulldozers, graders, enormous concrete mixers, all roaring away. It looked like a Manchester Wimpey site. We discovered that all the work was being done by the United States Army ‘CBs’ (Construction Battalion). Their motto is as simple as is true ‘If it can be done, we can do it!’ When one considers that they have constructed a massive base which is occupied year round at the South Pole, this is clearly no idle boast.

With even more time on our hands, I commandeered the ‘Quest’ taking a group of FIDS out to a penguin rookery for a ‘photo shoot’.

When our repair work had been tested, we set off north again and en-route we followed a large pod of Sei whales, getting close enough to take photographs. I noted in my diary:-

‘Some ship this ‘Shackleton’, allegedly on survey yet breaking off to go whaling!’

After these several delays we finally dropped anchor in Whalers Bay, Deception Island on 23rd January. We got stuck here due to poor weather for a further four days, during which, despite the dire conditions, I managed a few interesting walks. There was much to see due to the devastation caused by the eruption. Great fields of pyroclastic ash lay everywhere and the damage caused was hard to comprehend.

We had gone stern to, with the ship anchored to the shore by lines fixed to the old machinery of the whaling station. Unfortunately we had to haul in the lines as the one anchor we had down was dragging, turning us dangerously beam on to a lee shore. A sigh of relief was almost audible when we got the ship clear of the shore. We engineers were acutely aware of the dire straits we would have been in if we had not fixed the starboard anchor windlass. With an hour’s careful and skilful manoeuvring by our deck officers, we finally got two good anchors down and hauled back on them to get the stern back on the beach, and our trusty ship, well aground in the ash, lashed firmly to her shore side anchor points.

The weather continued poor with strong winds and blizzards, but despite this some of us managed to get up to a small glacier high above Whalers Cove which enabled us to peer down on New Island. This long black ash mound at the very head of Port Foster had been ‘born’ during the eruption. It was still steaming but there were no signs of impending doom.

Difficulties with the safety of the ship due to the high winds seemed unending. On 26th January, the 2nd engineer and myself went ashore to de-ice the pump we had put ashore in order to take on water from the spring. When we had sorted this out we noticed that one of our stern lines had been almost cut through due to the excessive movement of the ship in the persistent gales. Frantic shouts to those onboard eventually resulted in a new line coming ashore, which with ice encrusted hands, we eventually got safely anchored.

Following the eruption, the water supply from the spring had slowed down so re-watering the ship was taking forever, and it wasn’t until the following morning that we finally got back out to sea and safety.

We commenced our seismic survey programme which entailed the same sort of monotony as the magnetic survey with the slight advantage of exploding charges of TNT. The ‘Shackleton’ became a ‘Pacifist Destroyer’, lobbing depth charges into the Antarctic seas hoping that we didn’t kill anything. One disturbing facet of this work was that whenever we threw a charge over the side, the Albatross, Giant Petrels, Wilson’s Petrels and Cape Pigeons (Pintardo Petrels) that were always astern in our wake, associated the splash with our regular disposal of kitchen waste, which they clearly looked forward to. They would ‘land’ en-masse, squawking and squabbling in quest of the imagined goodies, only to be rudely awakened when the blast went off, causing a mass take off akin to the start of a Thousand Bomber raid.

I can honestly record that I never observed that our subsea seismics resulted in avian mass murder. In fact the usual effects of our ‘depth charges’ was somewhat disappointing, which was a matter of some concern to the hordes of FIDS who always congregated at the stern, bristling with Nikon’s. For a true FID it was a sort of Shibbolith that, if you didn’t get a photo of it – it never happened or did not exist. Having some sympathy for their dilemma, we decided to try and float a 25 lb lump of TNT using old fenders and the like, in the hope that we could replicate something as dramatic and impressive as the explosion of a depth charge, as seen in your average World War Two film on submarine warfare. Sadly, this was a bit of an anti-climax. A burst fire hose on deck would have been more spectacular.

After days of this work we received a signal that the ‘Grey Ghost’ (HMS ‘Protector’) was on its way to join us for our two-ship seismic work. This venerable Second World War vessel had been dubbed with this nickname as no one ever really knew where she was and invariably whenever we saw her, she would simply emerge from the mist or snow, like a lost wraith.

We rendezvoused with the ‘Grey Ghost’ in mid-February and managed to complete several runs during the following week before she disappeared as ephemerally as she had arrived. The ‘Protector’ had transferred mail to us, and I was informed by ‘Frosty’, with obvious delight on his part, that he had received a reply from Bill Sloman, who was in charge of BAS recruitment, regarding my resignation and request for a GA job with FIDS at Stonington. He seemed exceptionally pleased to read a bit of the letter verbatim ‘With regards to the GA’s job, Curphey will have to take his chance with the others.’ While being gratified that ‘Frosty’ had forwarded my request, the reply did not seem too encouraging!

We continued seismic work on and off for the next few weeks, with occasional visits to Deception, Signy and the Argentine Islands. It was here that I first met Bugs McKeith, a well known Scottish climber, Craig Dubh member, and bound for Base ‘T’ Adelaide Island, as the dogman for the two teams there. I mention this here as his activities during the year ahead were to affect me in 1969. But more of this anon.

Towards the end of the month, as the ice conditions improved we managed to get into the base on Adelaide Island where I contrived to get ashore. This was the first time I’d been on land, south of the Antarctic Circle. During the staff change, Bugs McKeith took up his new post and I had my first encounter with real working huskies. One of them bit me!

During our brief stay, one became fully aware of the potential for adventure on these southern sledging bases. During the summer small single engine aircraft flew down from Canada to provide assistance to remote field parties, and while we were working cargo etcetera, we learnt that the Pilatus Porter short take off and landing aircraft, had landed to resupply a FID camp up on the plateau, south of Stonington and broken a ski hereby rendering take off impossible. As there was no chance of any rescue attempt, the occupants were forced to manhaul down to the survey’s most remote station at Fossil Bluff and spend the winter there. The almost new aircraft was left to the mercy of the wind.

We headed north again arriving in Port Stanley in the first week of March where we overhauled our two generators prior to going out on trials to test a new seismic profiler. This device, which consisted of the means to discharge long bursts of air at some 15,000 PSI was intended to improve seismic survey work and do away with having to carry and use large quantities of TNT. After a couple of weeks of this which produced mixed results and several technical problems, we returned briefly to Port Stanley en-route for South America, where we were to disembark several groups of homeward bound FIDS, intent on making the almost mandatory detour home by wandering north through the Americas. One ambitious troop had even had a brand new Land Rover shipped to Port Stanley and we now had this safely aboard the ‘Shackleton’, along with its crew of intrepid motorists. They disembarked in Punta Arenas on 22nd March and the old ‘Shackleton’ returned to the Falklands for the last time this year. By the 25th we were alongside at Port Stanley.

It was all over bar the shouting now, but prior to leaving the Southern Oceans, probably for the last time, given the feedback I’d received from ‘Frosty’, I did manage a final wander on the hill.

The Chief Engineer had made an arrangement to go on a fishing trip where he would spend a night at a remote sheep farm with a Falkland Islander called ‘Sloggie’, who knew the shepherd. Myself, and John Noble, an outgoing Stonington FID and keen climber, invited ourselves along for the two day trip. It was our intention to go out to the farm, walk over to Mount Lowe and climb there, spend the night in Sparrow Cove and return in time to get picked up the following day.

From my diary:-

‘Up and away by boat at 0630. We went up the Murrel and by 0800 we reached the farm. We all went ashore in the dingy and Fuzzy John set off back in the ‘Quest’. The shepherd at the house was arseholed. We bid him a cheery “Good morning” which earned us a “Bollocks to you” reply. John and I left leaving the Chief and ‘Sloggie’ to get on with it.

We walked over to Mount Lowe, at last a chance to climb the big slabs. After we had eaten and made a brew, we started to climb. The crag was virtually split into three and we made a route up each face. I really enjoyed it, the grades being about V Diff to severe and the longest route some 250 feet. All quite exposed and without any big ledges made for fine climbing. The angle was steeper than Idwal Slabs, a lot steeper.

Definitely one of the best days I’ve had down here in the Falklands and certainly the best rock climbing. As the evening drew in we came off and walked towards Sparrow Cove (where the SS ‘Great Britain’ lies). John had fine blisters on his heels, so he went straight down, while I walked on towards Kidney Cove in the hope of getting some good wildlife photos, but I turned back after a while, as I couldn’t have made it before dark. I walked over to the cove and found John all set up in the house there.

It was our intention to bivi out but the house was empty so we moved in! We cooked a meal and then listened to the house owners radio until about 9 pm, when we turned in. We slept well after our day out on the hill. Breakfast was astern by 9 am and we set off back, arriving at Murrel House about 1 pm. Hector, the shepherd was most welcoming remembering nothing of our earlier meeting, so we spent a pleasant hour or two drinking tea before ‘Sloggie’ and the Chief returned. The ‘Quest’ picked us up and took us back to Port Stanley.

On 1st April 1968, we were homeward bound at last. After a brief halt in Montevideo for bunkers and a run ashore, we docked in Southampton on 30th April, having covered some 35,000 nautical miles, my longest voyage to date. I was glad to be home.

The summer was somewhat difficult personally, and my future uncertain. Prior to departure, I had made arrangements to lead a small expedition to Iceland and this was carried out (details of this venture are included in the previous chapter).

As the year progressed I had necessarily given up any hope of returning to Antarctic as a dog team driver, and my financial status meant that towards the end of July, I was desperately seeking employment. To my amazement and unending joy, on the 28th August, the day I was to attend for a promising interview with a Stockport engineering company, I received a letter from BAS informing me that due to the sickness of one of the GA’s at Adelaide Island, I have a job should I want it. I took it with more joy than I would feel had I inherited a vast fortune. I was going south ‘proper’ at last by courtesy of one Bugs McKeith.

Ian “Curph” Curphey – (eventually) Adelaide GA, 1969

Two more Chapters from Curph’s unpublished book will be published on the Adelaide page, 1969 – two Southern Journeys – surely another great read.