Veterinary Corner

A Summary of Vets and Huskies in the Antarctic – Tony Palmer

With Acknowledgment to Veterinary History and Thanks to Dr John Clewlow, BVSc MPhil FRSB MRCVS (Editor)

Huskies or sledge dogs were first introduced to the British Bases in the Antarctic by the Falkland Islands Survey (FIDS, later British Antarctic Survey, B.A.S) in 1945. No professional attention was provided for these animals until 1963, when M.F. Godsal, a Cambridge veterinary graduate, was recruited by BAS.

Read on to Dr. Palmer’s Veterinary Summary here

A Few Notes on Veterinary Conditions – Bob Bostelmann

Basically the dogs were extremely healthy and most problems were caused by trauma, especially fighting.

There were two major outbreaks of disease. ‘Signy Neck’ occurred at Signy between 1956 and 1960. This was a cervical lymphedenitis from which 17 dogs died. The lymph nodes in the neck swelled up (like mumps) and, as I understand, the head swelled as well so the dogs could not eat. This was said to be caused by Erysipelothrix which is a bacterium found on seal’s skin which caused ‘sealer’s finger’. This disease was a very swollen finger. This association was never proven.

In April 1971 eighteen huskies were simultaneously affected with a condition known as ‘foot lurk’ although the dogs at the time were at Stonington, Adelaide and Argentine. Over the next 10 months another 21 dogs were said to be affected although I question this and think that drivers were calling any skin condition ‘foot’ lurk. The proper condition was a severe ulceration of the pads and the skin around the pads so the dogs were severely lame and unable to work for up to 5 months. Working backwards the common demoninator was that all the dogs were working seal at Stonington a month previously when they had dragged seal up the beach in which the rocks were exposed for the first time in recent years. The theory put forward was that the ringworm which I found in samples that had been sent to me in Cambridge had lain dormant in the soil around husky carcases near the old Finn Ronne base and that, due to the enormous thaw that took place in the austral summer of 1970, this was exposed to the dogs who also had small cuts around the pads from working over the rocks. Unfortunately, while I was south I was unable to culture the fungus from any samples I collected.

(Dr. Bob Bostelmann – Stonington, January 1974)

Most of the skin conditions I saw were associated with ice and snow in which various bits of harness had become frozen to the dog, or the snow had frozen into the coat which the dog often then pulled off leaving bald patches, the famous ‘donglers’. I drove two Greenland huskies and found that they were for ever stopping to chew their feet where the snow had become balled up between their pads, while the BAS husky would still pull even though he had a great mass of snow under his foot. The BAS dog however hated having snow all over his face and would frequently stop to rub his face along the snow while a Greenland dog would run all day with a great mask of snow over his face.

BAS Dog Food

BAS huskies were fed approximately 6 pounds of seal meat every other day while they were on base; any extra blubber, skin or bone attached to the joint was extra. This was fed whole, usually frozen hard but was demolished within 10 minutes by the dogs.

When sledging the dogs were fed Nutrican (Nutty) which came in individually wrapped blocks of one pound. They were given one block per day for two days and then 2 blocks on the third day but like their human drivers they lost up a third of their base weight especially at the beginning of the season when the snow was deep and it was still very cold.

Bob Bostelmann, DVM – GA Stonington, 1973

Why Have a Breeding Program?- Andrew Bellars

Unfortunately, from the breeding point of view, the BAS Husky population is very small and so provides a very limited genetic pool. In the past breeding has been very indiscriminate and as a result two hereditary conditions have appeared — Haemophilia and Entropion.

Haemophilia is a condition in which one of the blood clotting factors is missing so that the dogs bleed very easily. Entropion, discussed in the eye section, is an inturning of the eyelids.

It is not known exactly how these conditions are passed on genetically but as they are both recessive characteristics they will become more apparent by inbreeding. Thus these genes are probably present in the BAS husky population but by out-breeding they will not become apparent; by not breeding from families that we know are carriers (i.e. they or their offspring have shown clinical signs of these conditions) we hope to breed these genes out of the population.

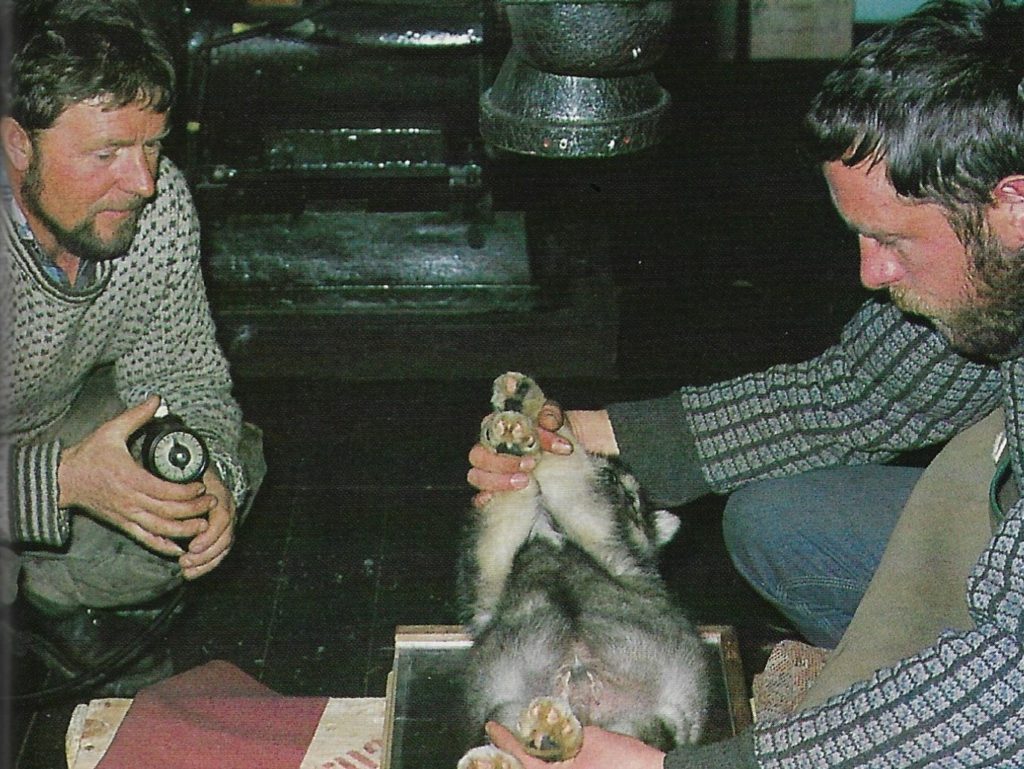

Some of the Work of Mike Godsal and Andy Bellars

From 1955 onwards the regulations about breeding of BAS dogs had been property established. All dogs had registered names that indicated the date and place of birth with details of the mother and sire. The record cards were kept up to date and details sent back to England at the end of each season. Dog numbers had steadily increased and there were now over 170 on the register. However there was some worry that the dogs were tending to age and become stiff sooner than they should after only 6 years, compared with 8 or 10 years for other dogs. A qualified Vet, Mike Godsal was asked to visit the Peninsula in the season 1963/4 to give advice.

The Last Antarctic Amateur Vet – Charlie Siderfin

During the winter of ’93 (at Rothera) the majority of the dogs were getting on. True, we had the five “Pups” who were two years old, but the rest were all over six and some of the dogs were nine. As a result we seemed to get more than our fair share of dog illness.

The week before leaving the UK, I paid a flying visit to Bob Bostelmann (Stonington Vet 72-74) en route from Aberdeen to London, having just completed three months training with the BAS medical Unit. Bob had kindly offered me the opportunity to spend a few days with him to learn some tricks of the trade, but time only permitted an afternoon. As it was I was late and my veterinary training was limited to an overweight poodle and two cats.