Bransfield days 1972 to ’74 – Bosun Robbie Peck

Photos by Robbie Peck unless credited otherwise

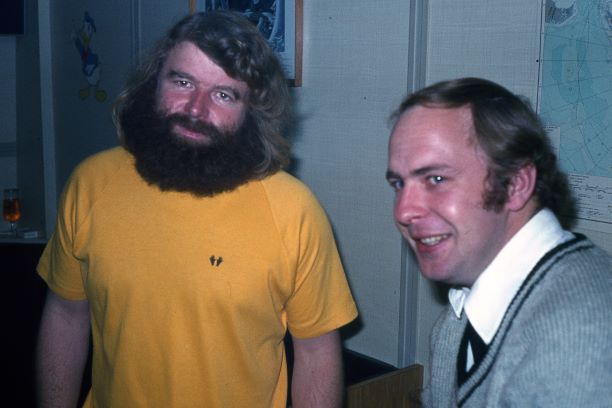

Sorting out a crew

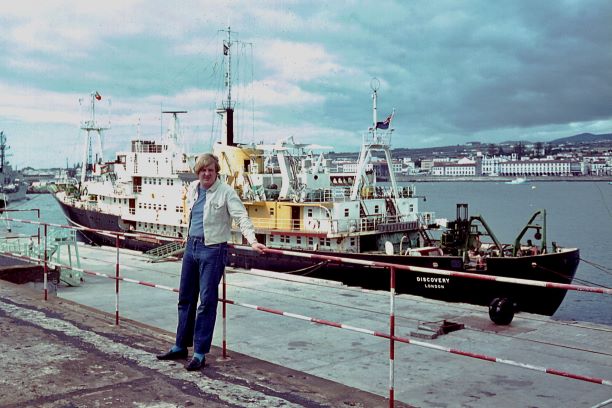

How I got the bosun’s job on the Bransfield was a funny old coincidence really. I’d been working on the Discovery for NERC for a couple of seasons after the Shackleton.

Then, one day the Discovery tied up in Southampton and I went into my local pub, what I’d always used before and the landlady said “There’s a bloke been looking for you, called John Morton”.

I said I reckoned it was for a drink and she said “Oh, no, it’s about work”. I told her I was okay for work at the moment.

Continuing from “Ships & Mariners” Page….

Anyhow, I phoned this bloke, John Morton, and we agreed to meet the following day and he said to me “Don’t get too keen about the next trip because you’re not doing it”

“Oh, aren’t I?” I said.

We met over a pint and he kind of interviewed me and told me about the Bransfield; he convinced me I could do it, should do it or whatever. Anyhow, they didn’t want me for a few months so I did sail on the Discovery for a bit longer.

Then, it was up to Leith in Scotland, for the guarantee refit work. This is where I met Captain Woodfield for the first time and of course Ella, who became his wife. She was our office girl.

In the same yard they were building a large tug called the “Englishman”. The mate tried to persuade me I’d be better off with them, but I didn’t fancy tugs and Bransfield was already beginning to excite me. So, I was bosun right from my start on the ship.

Captain Woodfield used to look me up and down, I think I was rather frowned on in the early days. We used to mix with the Biscoe boys and I think there was a bit of a thing between the two captains. Anyway, once I’d been on there a few weeks he sort of accepted me and we got on fine. Still, I was always a bit cautious of him because, like Frosty on the Shack, he had a bit of a look about him.

When it come to crewing up the mate got me involved because I think they’d had a pretty rough lot that first trip, rough like useless, cos they had had to leave in a bit of a hurry. Ship was late, all the ships is late, aren’t they when they come out from the building yard?

I got a couple of crew off the Discovery, one was a lad from the Shetland Islands, he had been the launch man there.

The mate would say – ““Do you think he need’s an interview, I’ll get him down?”

I’d give him a look over “No, he’ll be fine” and so it went on. He’d ask about this bloke and that bloke and I’d say “Yes” or “No”.

We interviewed two blokes who’d been south with Salvesen on the whalers, they could do a bit of grafting. Ron Dixon stayed but two thirds of the crew were new on her second voyage in 1972.

One morning the mate said to me “I wish I’d had you last trip because a few of them needed a bit of roughing up.” It’s how it was in them days; Crewing has changed a lot since then in BAS and in the merchant navy.

Kneeling L to R: ?, ? , Dave (Chin) Richards

Heading South – Leading from the front

I kind of led from the front, I got out and did the jobs with the boys. You’ve got to work to create happiness amongst the crew, the bosun has to work with the Fids too because to a great extent it’s their domain.

I remember when we’d sailed from Southampton my first trip I’d gone and done something and when I come back round the corner all the lads were standing by the hatch having a cigarette, then they all disappeared. I said to them afterwards.

“Look, I’m just a crew member as well. I work with you and just because I come round the corner I don’t expect you to scarper. If you’re having a ciggy, you’re having a ciggy and that’s fair enough with me.”

That’s how I got on. I tried to lead from the front. I always enjoyed Bransfield; it was one big happy family. I liked to get myself known, I’d work with the engineers, got along well with the chief engineer, Tony Trotter. I always worked closely with the King Fids.

Once we’d got away from the UK and were clear of the land and the weather was improved we’d get the Fids out helping on deck. We generally had a lot of chipping and painting to do on the decks and bulkheads. I think most of the Fids quite enjoyed it really. If they didn’t have something to do I expect they’d have gone bonkers just sitting around all day and night. They had a good mess room and bar at the for’d end of the accommodation block and their dining room was as the aft end. Also, they were doing the lookout job during the night with the watch keeping officer. Now, we could have all our lads on daywork doing the splicing as well as the ship maintenance. I suppose we got an idea which of the Fids was going to be good when it came to cargo work and working in the scow and that sort of thing. You know, you’d get a feel for it just talking with them. Some was really keen and interested and some, well you just knew they couldn’t be put anywhere they might get their fingers or head in the way. Same with painting, it would probably have been easier to give them another job cos you knew there’d be a lot of clearing up later. But, a lot had come straight out of university so why should they know, I accepted that and really, I was glad of their help. I think it really helped with them getting to know each other, and us bunch. Some of the mechanical Fids worked in the engine room and a few liked it so much that after their Fid time south they signed up on the ships.

I didn’t get involved much in hobbies. I think I was just busy keeping an eye out on things. One of the interests in these early trips was making belts, this macrame fad. They’d do all sorts of different weaves with the nylon strands making up the belts. I was into that, I made a belt, my son, Dave, has now got my belt, spike and knife. I was also given a belt, it’s upstairs somewhere. Of course, the Fids wanted one too, so there was a lot of making and teaching, it was good because it brought people together too. The three decks, officers, Fids and crew seemed to work pretty well. We mixed quite a bit with the Fids and sometimes the officers would come down to our bar and the Fid’s. It’s all a bit different now on the new ships, not even sure they’re allowed a drink, which seems pretty sad to me.

Once we’d left Montevideo everyone began to get a bit excited and the weather usually began to change. We’d start getting rough seas again before Stanley.

In Stanley the Fids would break out their full base kit. They looked really clean and smart in those hairy shirts and moleskin trousers and I always wondered how long they would stay like that. I don’t think their washing facility on the bases was much in the 70’s.

Peninsula bound but Halley in mind

After Stanley we might go left or right. A lot depended on the ice conditions down the Peninsula and Halley. Anyhow, that wasn’t my problem, thank goodness. There was a lot more interest now from everyone as we got in closer with the ice or the islands and I think the Fids, particularly the first timers, were changing; you could tell they were beginning to think they were almost home. They’d had a month of stories from the older lot, the second and third timers, so something must of rubbed off.

Halley Horrors

It didn’t matter whether it was Halley or the Peninsula, cargo work was often dangerous and I don’t know how we never had a fatality, I never heard of a serious injury.

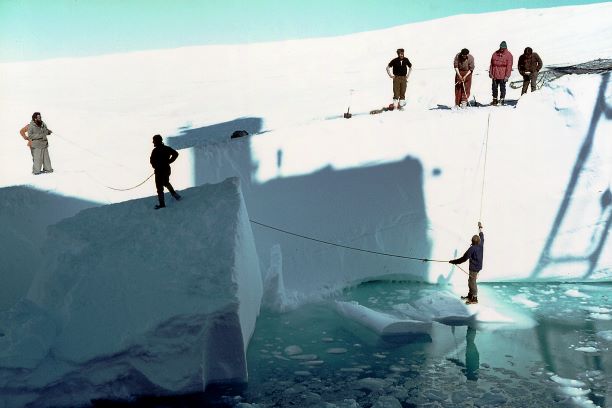

At Halley Captain Woodfield would try to find one of those creeks that he could stick the ship into because then he could tie up with a big bit of flat sea ice to work cargo but there had to be a ramp up onto the ice cliffs for the vehicles to tow the sledges. Sometimes there wasn’t any sea ice or it might break away during operations and we’d have to find somewhere else and that might be the ice cliff level with the bridge.

When we had to leave an ice edge it was often in a rush, with the wind and swell getting up and then we might have to go outside and wait on better weather.

The Halley Fids would send a tie up party down and we would offload people on the end of the crane hook, really health and safety stuff. Then they’d all go pulling the head lines and stern lines up over the massive cornices and ice cliffs, along the shelf to where the deadmen were dug into the snow and about four hours later the ship would be tied up. Cargo discharge would start soon after. Halley was always a twenty four hour operation, so two shifts were set up. Everyone got stuck in and the cooks were on shifts to provide meals round the clock. The mate on duty and I or the bosun’s mate had to have eyes in the back of our heads because now was the time someone could get damaged by a swinging bit of cargo or a wire whipping suddenly or just a dangerous cargo lift. There was just so much going on in the holds that we were responsible for and these guys had usually never been involved with anything as dangerous. Then, there was the ice edge to watch for.

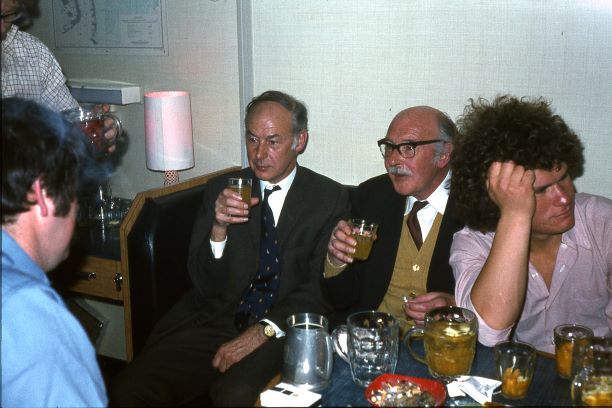

One year the ice did break up and we had a couple of blokes stranded on lumps of ice. We got ropes to them and we picked them up with the crane. I remember, one was fishing around for his glasses which had fallen off and of course he couldn’t see anything without his glasses. Captain Tom was shouting at Stuart Lawrence, the mate, to hurry up “I can’t keep the ship here any longer”. Yes, we had our moments. This was the trip we had Sir Vivian Fuchs on board, so it must have been his good bye trip, 1972/73.

Another time, Ron Dixon and I went out for a walk to get some grips of the ship. We took some of the ship lying all quiet but when we got back on board and we was sitting in the mess all hell broke loose and she done a violent roll. All the beer kegs we kept in a cupboard came flying out and you could hear the fiddery above us being demolished by chairs and everything going over. When she finally came upright I shot out of the watertight door and could see she’d dipped the gunwhale because there was water and slushy ice on the foredeck but there was a mass of ice right across the deck where the cliff had collapsed on us. We spent the next fifteen hours or so just clearing the ice off and eventually assessing the damage, which luckily was only bent bulwarks and some broken air vents. It was just incredible that no one was around and I think it was because we had a delay with cargo sledges otherwise people would have gone straight down into the water when it collapsed and anyone on deck would of got crushed. We didn’t have any safety gear in the early seventies. No hard hats, no lifejackets. Even our warm clothing was really whatever you could find to keep warm at minus 20C or colder. We sometimes managed to get Fid gloves, which were a bit better than our cheap working gloves. Our issue clothing was pretty poor.

Getting the big vehicles off and on the ship was always a challenge, well the whole operation was. You just didn’t know from year to year and it was the place that tested everyone’s nerves, especially the captain and mate. I don’t think the engineers rested either because they would be called to get the engines started if the ice broke up. So, they couldn’t do any serious maintenance tied up at Halley.

We had our funny moments too. I remember Gordon Ramage, ”Ramage the Damage”. He was one of the base mechanic and had just received a new consignment of skidoos. A few hundred yards from the ship he was having a bit of trouble with this bright yellow beast and he was giving it a good talking to. I got up to him and we was joking about this stroppy machine and he was pulling and pulling the starter cord and I don’t know what happened but it burst into life and Gordon, who was knackered by this time, was on his knees and just couldn’t get up in time. This yellow skidoo just started to go and it didn’t stop. I was laughing and weeing myself and poor Gordon was watching terrified as this skidoo just got smaller and smaller and the gang of people on the ice unloading the ship suddenly parted into a very large V as this machine roared past them, slammed into the side of the ship and quietly sank. Gordon turned to me and said “I think I’ll be coming back with you”. He wasn’t laughing.

The Odd Dingle Day down the Peninsula

The Peninsula had its moments too. It was great when the weather was dingle. Even Adelaide was a treat, well you needed it good when you had a large vehicle to get on or off at Adders. There was some funny occasions there and we lost a few over the years but I’ll let the mates responsible tell their own stories about disappearing vehicles.

The big difference between Halley and all the other bases was the scow. We had a large wooden one and then in later seasons we also had the big steel one, “Big Red” which was great because it didn’t leak, but getting it into the water or back on board in a swell was really difficult. You had to have it well bowsed in when lifting and swinging and then two of the lads had to go down in it to unhook it. You could have the whole lot swinging around and the scows going up and down, seas breaking over the bow and I’m thinking ‘ is this lot safe’. I thought that occasionally but I knew I had a good Mate in Stuart Lawrence and I had some damn good lads on deck. It made all the difference and I could discuss it all with Stuart. We didn’t take chances, well, not too many. But, the pressure was always on to get a base done and move on.

The Fids who helped in the scow when we were working were keen most of the time. They quickly got the hang of a moving scow, a moving cargo sling and even their moving stomach cos sometimes it was that bad and it was all happening at the same time. The temperatures were often around minus something and if it was windy and snowing and water coming over the bow it wasn’t much fun in that scow. Then, the work boat “Terror” or sometimes the posh one, “Erebus” with the cab, would tow the scow in to the base. Even then they might have to be fending off growlers and bits of pack ice. Adelaide was the worst of the lot in anything but a calm day. If there was an Adelaide swell the scow would be up on a wave one moment and landed on the jetty the next. The workboat was stood off to protect it from damage. It wasn’t much fun.

We used to call Adelaide Iceberg Alley because those bergs would come flying down where we were anchored. It wasn’t too far from the base but sometimes we’d have to move the ship if the berg looked like it was going to come at us. At night the crew used to do the anchor watches and if a berg looked like it was getting too interested in us or if the wind got up or it looked like we were dragging anchor they’d call the duty mate to check it out. We’d always be glad when Adelaide cargo was finished.

Now, I’ve got to tell you about the speedcrane, that’s the one at number three hatch. It was a bit of a devil and I enjoyed driving it once I’d got the knack. Early on when Chris Elliott was mate he’d say “I don’t know how the hell you do that…” I had a secret challenge, I used to try and make him run as fast as I could from one side to the other when he was doing the hatchman’s job. I’d have my knee on the cut out button and use the override button, which would let the derrick go lower and it was ages before I told him how it was done. Once you got used to it it was a brilliant bit of kit if you mastered it. But, if it mastered you it was a different ballgame. The year I joined Bransfield they had put the slewing guys further outboard, which made it a lot more controllable, but I wouldn’t say friendly.

The work boats were on self tensioning falls so in bad weather you could release them and retrieve them, but it could be hairy stuff too. You had to have competent and confident blokes on each hook ready to lock on otherwise the boat could be left dangling from one fall. Late nights back for an Adelaide party was always one to be wary of when you had a boat full of pumped up Fids to collect or deliver.

Times up for Adelaide

My last season, which was 1973-74, we were looking at a new site for Adelaide and a bit further up the island a spot called Rothera had been numbered. I remember we had to go and do some sounding work. There was two bays and we didn’t really know what they were like. Well, South Bay was too deep to anchor and North Bay was too full of rocks to get in safely. Captain Woodfield did get into North Bay and we poked around getting a lot of soundings, which kind of proved the point. It was only in the following years after I had left that they started to build the new Rothera base, which today has grown to something I can’t even recognise, what with a massive jetty and airstrip with a control tower.

At Adelaide Captain Woodfield said to me “If you want to work nights here I’ll make sure we have new Years at anchor…” Well, he didn’t need to encourage us further. We got Adelaide done and had our Christmas there then after a quick visit up to the Argentine Islands we headed off for the Beagle Channel and anchored for New Year’s eve. Ella was with Captain Tom, it was their honeymoon trip and I’m sure Tom wanted to show her the Channels by twilight.

I knew this was going to be a massive party and I kept myself alcohol free kind of thing. Sometime after midnight and what seemed like the whole ship was in the Fiddery, but not everyone because there was this bloke, forget his name now, but he was from the British Embassy in Monte and he was a passenger and he started off. I saw him leaving a fire extinguisher on our deck outside the messroom, then he started up to the Fids deck and was outside the fiddery when I caught him. He’d just got hold of a water extinguisher and fired it into a Fid’s cabin. In those days they all had big cameras and reel to reel decks. I’m afraid I just lost it and landed him one.

Then I thought – Not a good move, Robbie! Anyway, it had happened. Stuart Lawrence, the mate, wasn’t over impressed. “Robbie, that was a bit silly”. This gentleman gets taken in to see the doctor and had some stitches put inside his mouth and everything’s alright again.

Ah, I was going to be on the wheel when we lifted the anchor next morning so I was going to be facing Captain Woodfield. Not so good, Robbie.

I’m on the wheel, its calm and still, and the cables coming up. Five shackles, four shackles. Oh, God I’ve got to say something soon. Three shackles. Come on, say something. Then I blurt it out.

“Captain, I’ve got to report myself” as he’s passing the steering console.

“Oh, what have you been up to Robbie?”

I replied as calmly as I could “You know this Second Secretary chappie, well, I lost it with him last night for letting off fire extinguishers and I smacked him and he’s had to have stitches in his face”

“Okay” he replied, with that stern look of his. And then he marches straight to the phone and calls Ella.

“Will you come to the bridge”

And I thought, oh Christ, he’s going to have her as his witness for a logging. Anyhow, he says.

“You better give Robbie a pat on the back” and she says “Why’s that?” He’s looking straight at me now, with a big smirk. A pause, then – “He thumped your mate last night”

And I thought my God, I’m safe.

Captain Woodfield told me he wasn’t going to do anything about it, but only problem was that on his way home the Second Secretary would be meeting Dr Laws, our new director, in Santiago. Give him his due, when the Second Sec. left the ship in Punta he did apologise.

When Dr Laws got aboard that night, Captain Woodfield called me up to his cabin and said – “You’re alright, he told the director he fell off a table being silly”.

I’ve talked of Halley and its problems and challenges for a bosun, but that was in a general sense. We took our memories and hung on to them because they were very strong.

Frozen Memories and Epic Futures

Dr Laws is now aboard and we are heading for Halley, it’s January 1974. It wasn’t a bad passage through the ice although one trip blends into another but nothing bad happened. We got in to one of the chips and done our unloading and then waited for a Twin Otter aircraft to fly over from Adelaide. That was a big deal back then. The plan was to head off south towards Shackleton base, Sir Vivian Fuchs trans Antarctic depot hut. Last season(72/73) with Sir Vivian aboard they found it. This year Captain Woodfield again stuck the bow up onto the ice edge and people clambered off over the bow striking out with ice axes and ropes. There it was, not far inland. I was privileged to go along this time and remember thinking I’m going to keep one step behind him ‘cos he knows where he’s going and I don’t want to be disappearing down any of them crevasses. I don’t know how, but he just seemed to sense his way in and down and we sat in the hut sort of suspended in space under the ice. It was an amazing feeling and I was so glad. I felt honoured to be in such high company.

Blowing Snow at Shackleton BAse

Nose-in

Going Ashore

Sir Viv leads the way

Shackleton Base

That’s maybe how I felt then. We had our methods and now our memories. My son, Dave, started on the Bransfield in 1986 and moved across to the James Clark Ross and there he was bosun/science officer. He and my grandson, Daelyn will shortly be joining the SDA. Dave will be science officer, working with the head of science, operating all the winches. They, as members of the crew, have become part of a massive organisation, a business really. It’ll be another world. I’m happy to remember the sense of adventure then and happy to recall each voyage was called an expedition. Different pressures, but I’m proud the pecking order has allowed three generations of Pecks to experience a great organisation.