Dogs, Theodolites and Crevasses – Angus Erskine (continued)

From Radio conversations with Tom Murphy, the 1956 Base Leader, I knew there were two dog teams, of 8 dogs each and that since the death of the old lead dog, teams were always led by a man on skis. I should mention that Tom and his crew had done a great job in 1956, building the base and finding a route up on to the mainland plateau among other things and they had had little time to spend on training dogs. I made up my mind to build up 4 teams of 9 dogs each with a good leader – dogs who would pull hard and who would obey steering orders without having to follow a man in front. It would then be possible to have a team for each of the two surveyors, another for the geologist and a fourth for general duties, each of which could, if necessary, travel independently. I was keen on one man looking after and driving one particular team throughout the year so that the dogs got to know their own driver, for maximum efficiency. Although I had driven dogs in Greenland in the fan formation (line abreast) I had decided to drive them on a centre trace (line ahead, 4 pairs and one leader). My reasons were partly to follow FIDS tradition, partly because I thought it was probably safer for crossing crevasses (admittedly a debatable point) and partly because I was interested in comparing the two methods. I was pleased to find that one of the new men arriving with me was a shepherd by profession, Frank Oliver. He turned out to be excellent with the dogs and play a special part in caring for the pregnant bitches and litter on base.

I was delighted to discover 5 dogs already at Detaille Island who had been with us on the British North Greenland Expedition 1951-54 although they were getting rather old now. Joanna had been the only bitch in my old team and had been spoilt abominably. She produced a litter of 7 pups, almost without fail, every seven months and her progeny was always high quality. I cannot pretend that she recognised me after a gap of more than two years but I certainly recognised her. As of old, she was allowed to run around loose and was as happy as ever although becoming too old for pulling.

We had about two weeks to unload the stores and take over from our predecessors before the ship was due to leave for a year and during this period I realised there was an immediate logistics problem; the fjord was unlikely to freeze over until June and we had no boats other than a small dinghy. So if we wanted to sledge on the mainland in the 3 month Autumn period, we needed to persuade “Kelly” (Captain Bill Johnston to give him his correct title), the ship’s skipper, to land a group of us, with dogs, on the mainland as soon as possible. Thankfully he agreed to do this and better still, he first put ashore at our landing place the timber needed for a depot hut which was duly built by a work party in just a few days on one of the few bits of flat rock on the coast. We called it Johnston Point. I made frantic preparations and on 2nd March, in somewhat inclement weather, four of us clambered ashore with 21 dogs selected rather at random, 2 tents, 3 sledges, a portable radio, a Valor stove for the hut as well as camping stoves, together with fuel and about 4 months food, part sledge rations, part tinned food. We waved goodbye and the ship departed.

As soon as we had got ourselves organised in our little wooden hut we established a training camp half a mile inland and from there begin to try out our dogs, taking them for runs on short flattish glacier surfaces, covered in snow. The snowline at the end of the summer, in contrast to the Arctic, is virtually at sea level. I had brought 21 dogs, thinking it would be easier to form 3 teams of seven while both humans and dogs were learning the game; in the spring we could add another couple of dogs to each team to teach the younger ones at base. It was soon clear that the dogs varied enormously in age, strength and experience.

It would take too long to recount the battles we had to identify suitable lead dogs, to stop dog flights, to catch loose dogs, to persuade any group of 7 dogs to pull in the same direction, to fix up harnesses and traces and so on. The pecking order in each team had to establish itself, hopefully without any casualties! Suffice it to say we endured weeks of exasperation, frustration and weariness. Eventually 3 teams began to take shape. We named them the Trogs, the Counties and The Girls. In contrast to my experience of the fan formation I soon discovered that with centre trace it was necessary to have a very special dog in the position of leader, on whom everything depended; without such a special dog you might as well stay at home and play chess. He (or she) alone of the whole team had to obey your orders to turn right or turn left – the others followed. Of course, the whole team had to obey the order to “Go” or “Stop”. In the course of time your leader would understand how many tens of degrees to turn, depending on the urgency of your voice and also, perhaps orders such as “Pull Harder” or “Trot Faster” or (when stopped) “Lie Down. Above all, the leader had to pull when ordered with no person or other team ahead to follow, nor any track, ands perhaps nothing to see except a white-out.

After trying out several dogs I eventually selected Bodger to be my leader. He was intelligent (for a husky) but he was also strong and, indeed, the top of the pecking order, the “King”. I knew from discussions with old hands that it was not necessary for the Leader to be King as well although it helps if he is a large dog when he has to make trail in soft snow. Bodger was black and white, aged 3, weighed 104lbs, had done a lot of travelling at Hope Bay and I became very fond of him in a year of sledging. His ability to understand my wheel orders was crucial in certain conditions on glaciers or sea-ice, and for navigating. My team was the Trogs. Jim Madell developed a strong team with two powerful dogs close to the sledge calls Herts and Beds, so his team was named the Counties. He had a Greenland dog called Jaikie as his leader. Finding we had several bitches, we formed a team called the Girls which Denis Goldring, our Geologist, took charge of, led by “Vesta”, a rather elderly but steady bitch from Base F.

I realised that the Autumn was a bad time to be on crevasse ridden glaciers. The first blizzards and snowfalls of the winter occur and new snow-bridges over crevasses have not always had time to consolidate so that the crossing of crevasses is particularly dangerous. We experienced some nasty situations with lead dogs hanging over gaping holes in their harnesses, but were able to rescue them with care; we took great trouble in making personalized harnesses for each dog, well fitting yet not too tight. Luckily the autumn snow was often soft so that the team was going slowly when the leader went down and the leading pair were able to stop at once.

Once the dogs were moderately controllable, we managed to make some useful journeys within a radius of about 20 miles. We were also training ourselves to get used to traveling on skis with winter bindings, with the ability to kick them off quickly when a dog fight started! Denis started to check out the rocks and Jim and I reconnoitred the area to select some prominent points for our triangulation and erected beacons on some of them.

In the middle of April we returned to our hut just in time for one of our bitches, Angela, to produce a litter of 5 pups. After a discussion on the radio, two of our colleagues from Detaille Island took advantage of a calm day to come across in a dinghy with an outboard motor, bringing another bitch and various items of stores and food; they returned to the island two days later, taking Angela and her puppies in a box full of wood shavings.

We were only a few miles South of the Antarctic Circle, so we knew we could continue outdoor activities throughout the winter, although in June there would only be about 5 hours of twilight each day. The main handicap to winter travel was the bad weather, blizzards which kept us pinned down in our tents, sometimes for days. In such conditions we would go out and feed the dogs every day, checking they were all right and that the drift snow wasn’t solidifying around their span. They would curl up with their noses under their tails and let the snow pile up round them. The best time for travel is always the spring and the summer, provided the snow is well below freezing. Wet snow makes for impossible and thoroughly unpleasant travel conditions. Meanwhile we were constantly asking on the radio whether the sea ice around Detaille had started to freeze yet, because I wanted to get back to base to do the necessary chartwork for our survey and to prepare for our main spring journeys. The answer was always “No”.

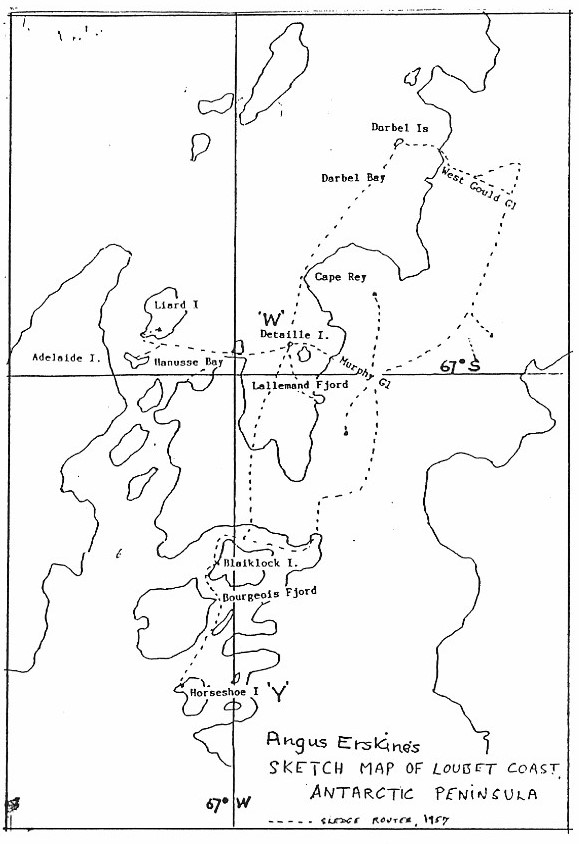

On 7th May we loaded up our sledges and set off on our purposeful Autumn journey. We ascended the glacier to the plateau, relaying loads all the way up, following the route pioneered by Tom Murphy last year. (This has now been named Murphy Glacier by the Antarctic Place Names Committee. Tom sadly died in 1985). It was hard going but the weather was good and we camped at the top, about 2000m above sea level, ten days later. Here we established a depot of food for future use, then Denis with The Girls, accompanied by John Smith, turned back, planning to visit rock outcrops all the way back to the hut at Johnston Point. Jim and I turned South along the summit plateau, starting a running survey but following a route close to that taken by D.P, Mason in 1946/7. Based in Marguerite Bay, he had sledged along the plateau in the summer but not descended any of the glaciers in our area. We made careful progress, steering a course by means of an aircraft compass on the handlebars and checking our distance with a cyclometer attached to the back of the sledge.

After one day the weather broke. We remained stuck in camp in a snowstorm with appalling winds for seven days. It was the most frightening experience I ever had in the polar regions. The drift snow built up outside the tent, bending the poles and outer fabric alarmingly and our daily expedition to check the dogs, feed them and sometimes dig them out became downright hazardous in the savage conditions. On one occasion I got temporarily lost only a few yards from my tent, with the wind swirling from different directions and hard snow flailing horizontally. I only found the tent when I bumped into a guyrope. But we were also worried about how Denis and John were faring – we could make no radio contact. We later heard they were in an even worse predicament than us, being caught in the open, away from their tent and had to spend two nights in snowholes, eating cold dog pemmican.

Mercifully, a short lull in the gale allowed them to regain their tent and safety. When we were finally able to travel, Jim and I dug out dogs and sledge; the dogs, incredibly seemed stiff but fit. We drove back to the depot to collect more food then proceeded Southwards along the plateau and after four days turned down the Finsterwalder Glacier towards the South end of Lallemand Fjord. This was new territory; no-one had set foot on this glacier before so we prayed that it would “go”. Going downhill was a perilous business, peering ahead to detect crevasses in the twilight. A snow petrel silently flying overhead was an ominous sight – they do not go far from open water. Sure enough, we soon sighted Lallemand Fjord with clear water despite the temperature of 0 degF. Instead of turning right towards Lallemand Fjord we turned left for Bourgeois Fjord which for some reason was still well frozen, intending to visit our friends at Base Y, Horseshoe Island, about 70 miles South of Detaille Island, and spend Midwinter’s Day there while waiting for Lallemand to freeze over. Percy Guyver, the leader at Base Y agreed to this on the radio that evening.

We found a route down a snow ramp leading from the vertical tongue of the glacier on to the sea-ice of Bourgeois Fjord. Two days later we were met by my old colleagues, surveyors Peter Gibbs and John Rothera from base Y with their team “The Admirals” and they led us to a refuge hut on Blaiklock Island where we stayed a while in comparative comfort and discussed plans for joining up our surveys. There was plenty of food for both dogs and humans here. A few days later, in temperatures of -28 degF, we hitched up and galloped down the smooth ice of the Fjord, 22 miles in five hours, where we had a great reception from the men there and revelled in the unaccustomed heat and light of a base hut. I even had a bath! Midwinter’s day, June 21st, was celebrated in great style and I talked with Johnnie Green at Port Stanley on the radio. On the 23rd came the welcome news that Lallemand Fjord was frozen over.

On 7th July, Jim and I and our dog teams were back at our own base, Detaille Island, 127 days after we had set out. The journey from Horseshoe Island had included the first crossing of the isthmus between Bourgeois Fjord and Lallemand Fjord via a col about 500m above sea level with a glacier on both sides. My leader, Bodger, excelled himself in obeying my steering orders through some difficult terrain and I was very pleased with him. I had given up using a whip at this stage. Denis Goldring and John Smith had, thankfully, got back from Johnston Point before us and were both well.

I was amazed to find out how much some of the young dogs, left at base, had grown and Frank Oliver showed me their youngsters as well as the new puppies who he was looking after so carefully. He had a small hut like a potting shed which was the maternity ward and mothers were fed well and given calcium tablets. During the next six weeks, as the days began to lengthen, Frank and others took our various teams out on relatively short runs, erecting beacons on several of the islands to help our triangulation network. We added two more dogs to each of the three teams, to make them up to 9 each and they were able to haul 900lbs with ease on the smooth sea-ice, although in practice their loads were not usually more than 500lbs. We also started a fourth team, mainly of young dogs, which we called “The Scrags”.

In August, Jim and I started the triangulation stations in earnest, taking advantage of every single fine day to set up our theodolites and measure angles between beacons. This involved sledging on sea-ice between the islands and the mainland and also on the lower slopes of glaciers. Denis also managed to reach rock outcrops on many of the islands around Hanusse bay to the West. From hilltops we could see that there was open water not too far away to the North. Among the sea-ice there were scattered icebergs, castellated, shining aquamarine in the sun and we soon found that if we sledged too close to the base of one of these silent giants we might put a foot through thin ice because they were rocking slowly and imperceptibly and the ice would not solidify around them. The sea-ice varied a lot. Sometimes it was as smooth as a billiard table; in other areas it was broken up into small bits by the wind and then re-frozen. Near the front of a glacier it was wavy from the pressure, in narrow channels it might be thin because the swift current prevented the formation of thick ice. In windswept areas we had to watch out for open cracks.

We revelled in the longer days in September but to our dismay the air temperature rose into the +20’s F and the surfaces became soft and slushy making sledge travel slower and heavier for dogs. We dog-drivers were fussy; we wanted no wind, good visibility and temperatures between about -20F and +10F – so did the dogs. We managed to position more beacons and to build cairns but the bad weather prevented us from actually taking the angles, a process that could take five hours.

Then at the beginning of November the whole situation changed. Denis Goldring and his companion Ossie Connachie, with The Girls, were overdue for their trip into Darbel Bay to the North. From high up we could see open water off Cape Rey so it became obvious that they could not sledge back to base and must have retreated to a small group of islands called the Darbel Islands where we had left a depot of food from the ship last February. I decided to set off with John Thorne, our most experienced all-rounder, with The Trogs, land at Johnston Point, sledge up Murphy Glacier to the plateau, travel North then descend to Darbel Bay down the only reasonable looking glacier named by Mason the “West Gould” Glacier, so far untrodden; thence we hoped to drive out on the sea-ice, if it was still there, find Denis and Ossie at the Darbel Islands and all of us return the same way. As it happened we would be covering sections of the Antarctic Peninsula which needed to be surveyed anyway.

And so it came about. The weather in October was far better than in September, and colder. The journey went as planned although there were excitements aplenty descending the West Gould Glacier whose lower reaches were riven with gaping crevasses. Denis and Ossie were at the Darbel Islands; the expressions on their faces when we arrived were joyful to see. We returned via the plateau again, ascending another arm of the glacier and keeping a running survey all the time. On the day when we were to pick up a food cache we ran into fog and I had to navigate from my own map, steering a compass course. Thank goodness, Bodger was in an obedient mood and followed my wheel orders carefully until out of the gloom the pile of boxes and bamboo poles appeared ahead.

By mid-November we were safely back at Johnston Point but alas the sea-ice was breaking up and we were unable to sledge back to base. We were stuck in our own little refuge hut until the ship came. So that ends my story about dog travel at Base W – but there is a PostScript.

The ship came and brought a new team of surveyors and supporting staff, except that Frank Oliver and Denis Goldring were to stay another year. The rest of us said a sad farewell to the dogs and sailed away. Years later I head the following story from him. After another year of hard work, tying up the loose ends of the survey and geological reconnaissance, they were faced with an unusually cold summer of 1958/59. The John Biscoe could not get close than 20 miles from Base W because of the thick pack-ice and even an American Icebreaker was held fast. A snap decision was made by the FIDS commander on 31st March to evacuate Detaille Island completely. Brian Foote and his men had to load all their personal belongings and scientific results on to four sledges, lock the door and sledge out to the ship. Two old and lame dogs had to be shot. The pups were anaesthetised by the doctor and put in a box that was lashed to the top of a sledge. They carried just one tent and emergency food. The ship shone its searchlights because it was dark by now and the sledge party was thus able to locate it. But one dog called Steve, born at Hope Bay in 1954, a strong dog in the Scrags team, somehow slipped his trace soon after leaving the island and disappeared. Everyone assumed that was the end of him. But, two and a half months later, on 14th June, near to Midwinter’s Day, he turned up at Horseshoe Island, Base Y, seventy miles South from Detaille Island, apparently in good health, having traversed two glaciers, shelf ice and sea-ice but no known trail. What a survivor!

Note: Johnston point is now called Orford Cliff, West Gould Glacier is now called Erskine Glacier.