Header Photo: The camp where we spent a week in a blizzard, in better conditions (Photo: Ian Curphey)

Autumn Journeys on Adelaide – Ian Curphey

It was to be 2 weeks before I could embark on my first field trip with the dogs proper. Rod and I had much to do and even more to learn. Under normal circumstances new GA’s join a base at the start of an incumbent GA’s second year and so get the advantage of learning the ropes by the tried and tested method of ‘Sitting by Nelly’, Nelly being the font of wisdom and experience, which brings understanding alongside knowledge.

Sadly we did not have the benefit of this. Bug’s had left base on the ‘Biscoe’ but even had he remained, Ian Willey had already intimated that “You’d have learnt bugger all off him – he was as much use as an ashtray on a motorbike in looking after dogs.”

So we had to learn the hard way. Fortunately both Rod and I were mad keen and we had all the help and experience of the other men on the base.

We spent several days just finding out where things were, what state the field equipment was in, checking stores, and all the essentials for camping out in temperatures down to -40 degrees and in winds that could blow at hurricane speed. We also had to make sure that all the seals we had brought ashore were properly stacked as failure to do so would have made life extremely difficult when the winter set in properly.

In addition to the particular interests associated with one’s official position on base, all hands were expected and needed to carry out the many duties that constituted what might be termed ‘Activities of daily living’. While these were not odious to any of us, they involved much more work than in a normal situation. For example, there was no water supply on the island for obvious reasons, so a big task for two people each day was to go out and cut enough ice either from icebergs out in the bay or from the ice of the Piedmont itself, to fill a large melt tank sited in the bathroom to ensure that water was always available. Similarly, our sanitary arrangements consisted of two cut down 45 gallon oil drums, one fitted with a seat and the other open. We only used the former for faeces and the latter for pee, the pee tin needed emptying more regularly than the ‘Honey Bucket’ which believe me had no sweetness about it. These had to be carried out on a very regular basis, taken down to the jetty, and emptied into the tide crack. For these fundamental tasks, and other more domestic duties like assisting the cook, we all had to comply with the ‘Gash’ rota. This was either loathed or hated, depending on our disposition.

These mundane matters were arguably as important as one’s official ‘work’, but attending to them ate into one’s time, so making haste slowly became the norm. Getting familiar with handling the dogs, sorting out the masses of equipment absolutely essential for surviving off base and building a new sledge ready for the anticipated long southern journey involved many late nights. Rod and I often worked in our sledge store (Stevenson Hut) until late at night, often with a ‘Tilley’ lamp for light.

Every day seemed to bring new insights into the amazing situation we found ourselves in and quite significant events were somehow transformed into the mundane.

From my diary:

March 3rd

‘Spent the morning trying to find a decent field tent from amongst the rubbish gear we have inherited. Clearly, there has been neglect by persons unknown that has resulted in this ruination of much originally expensive and fit for purpose equipment. Two of the three-man tents have great mildew marks on them, which makes one worry about their ability to withstand a 100 mph blow. Another has been burnt right through by the heat from a muskeg exhaust. Mike Bell gave me a hand and I finally decided that a two-man tent was the best bet. I stripped the old outer off and replaced it with a new one. Only problem was that the new outers are two guy and the inner is only one guy. This involved a big sewing job, but soon cracked.

During the afternoon, on a depot flight from Stonington, the single Otter’s engine cut out and the pilot Mick Green, had to crash land on the plateau. Yet another BAS plane bites the snow. A write off, fortunately, at the end of the season but nonetheless a blow for the survey. Derek Smith flew in with the Twin Otter and brought all the bods out, proving how indispensible two serviceable aircraft are for operations down here. No one was hurt, but yet another dead plane now litters the pristine Antarctic.’

Later on in the year, I sledged for months with Mick Pawley, a fellow GA who was onboard the single Otter when it crashed. I remember him remarking that he had only ever flown twice in his life – the second time in the rescue aircraft!

The preparation work continued apace, and by the middle of March things started to really come together and Rod and I received the official word we had been waiting for.

From my diary:

‘Did the seal feed with Ian Willey. As base leader, he has devised a helpful system which pleases Rod and I. Only one GA does the feed now, assisted by one of the other lads on base. Ian’s idea is to ensure that everybody has an interest in the dogs and it seems to work.

Continued working on my sledge and its really starting to take shape now, only a few small things to do (fit a rope brake, lash a fuel tray between the bars and rig a sledge wheel).

It’s getting colder now -9˚C last night. It doesn’t feel too bad, but its nippy around the ears if the wind blows at all. We are trying to get out on a proper shake-down trip in the next few days. Fortunately, we haven’t got a lot to do due to really getting stuck in earlier on. Terry the doc and Ian are coming with us.

The word is out that Rod and I are to be included in the Stonington’s Summer Field Programme so we are delighted, especially as Bug’s had put in his field report to BAS that, in his opinion, ‘the Adelaide dogs were no longer fit for field work.’ I’m sure Ian Willey ensured that the powers that be had a word to the wise. After reading the field reports, I suspect that with a bit of luck with the weather and ice conditions, we can look forward to a summer trip of four or five months duration. The whole concept of being here and travelling in the Antarctic revolves around dogs and the Nansen Sledge. It really will be a great pity when this model of travelling dies the death, as it undoubtedly will.’

By 16th March all was ready and I had made my decision as to which dogs to run.

The weather was a bit harsh for our first trip. Snow was falling and the temperature was down to -12˚C. In these conditions we were all aware that we would not be setting any records, but our enthusiasm was unbridled. At last we were underway.

Without exaggeration the work involved was tremendous. Trying to push the sledge when the dogs wouldn’t pull was heartbreaking. Ian Willey came with me and Terry ran with Rod. We had hardly got away from base when it became obvious that the dogs would not lead through, as the snow was so soft the poor buggers were up to their stomachs in the powder. With a tenacity born of ignorance, we plodded on, but after a couple of dog fights brought about by my beating Count to make him work and lead the team, we had to take it in turns to ski ahead, breaking trail for the hounds, as it was the only way we could get them to travel at all.

By three o’clock we were all completely knackered so we stopped and made camp for the night, still some miles short of the mountains. A lousy day’s run really, but good training for man and dog. I got terrible cramp once we got in the tent but felt better after we’d eaten. During the evening Ian told me that old Count had a habit of starting a fight when he knew he was in for a dose of the thumper. The cunning old sod must have worked out that, if he started a bit of a set to with the other dogs, by the time you had sorted that out by judicious use of the thumper, you would have a lot less energy to expend on him!

The frustrations felt during my first day out in the field were not easily overcome. We not only lacked knowledge, but more importantly experience. It was clear from the outset that this would be hard won. Even the routines associated with simply camping in these conditions caused endless problems. There was always something more to do and something you had forgotten. Clothes to dry out, harnesses to alter, Primus stoves that leaked, Tilley lamps flaring up and threatening to burn down one’s tent because you had failed to prime them properly. At times the task of simply surviving long enough to gain the necessary experience seemed tenuous.

These difficulties, each in themselves quite trivial, seemed to pile up on each other and steal precious time. Simply getting sorted out in the morning, cooking, packing up, harnessing the dogs etc took forever with the result that we never seemed ready to leave until the noon hour was past.

By the third day we had only covered about 17 miles and had spent more hours of hard labour to achieve this. The weather deteriorated and for the next three days we were tent bound. The wind howling and visibility down to almost nothing due to the spindrift and low clouds. Ian, who was a Met man before he became base leader estimated that the wind speed was up to 90 knots. It certainly shook the tent a bit. However, as Gino Watkins, Arctic explorer of the 1930’s once wrote ‘The weather always improves if you wait long enough’ and on our 8th day out things changed and we were able to ‘escape’ back to the base.

From my diary:

‘Up at 0730, wind still howling and it looked like another lie-up day. However, the wind dropped and we decided to travel. Digging our camp out took a long time. The tents were drifted up and deeply buried under snow, packed hard by the wind. It was 1400 before we got away. But what a difference. The blizzard conditions had packed down the surface and we fairly whistled along. Never have I spent my birthday like this. The utter joy of being behind a team of dogs all working well and even Count, my ‘Nemesis’ leading properly (doubtless aware that he was homeward bound!) He responded to the merest whisper of command. All the horrors of the outward journey forgotten as though by magic.

‘Still very ill, my head is a throbbing mass. My eyes remain permanently half-closed and puffed out with infection. The ‘plague’ is spreading. Great festering patches of bulging flesh keep creeping further and further around my wretched body. Every bloody inch of me throbs and aches with a sustained discomfort that I cannot find words for. Genuine sympathy has been shown by the lads but I’m not responding very well to the quips and the cracks – it’s all too serious to me.’

We arrived back at base at 1800 hours, having covered 17 miles in 4 hours. Three days to get out to Lincoln Nunatak and 4 hours to get back. The contrast between a bad and good days sledging was burnt into my mind forever. I’d had a very happy 27th birthday!‘

A week later we were out in the field again, this time Bill Taylor, a Met man but a GA at heart travelled with me on a trip that was chalk and cheese to our last.

From my diary:

‘A beautiful day, crisp and calm with a temperature of -9˚C. Visibility was several miles, with Alexander Island clearly discernible to the south. Rod’s team, the ‘Picts’ were a dog short, as Kon, who had come off worst in a team squabble the last time we were out, had a bad infection from the bite he’d received so he’s been left on the span.

We managed to get away by 11.30 and made good progress, passing our ‘farthest north’ of the last trip, some 4 hours later.’

The difference from our last struggle is almost unbelievable. We continued to make good progress and by our fourth day out we had reached the Shambles Glacier. This was of particular importance as it marked the route to the Leubeuf Fjord – our gateway to Stonington and beyond, the key to our hoped for southern journey.

From my diary:

‘A beautiful night. Enormous moon casting a halo and a lunar pillar on the snowy wastes. Up reasonably early and away by 1100. What a day, temperature down to -15˚C but brilliant sunshine. We headed towards the northern end of Mount Mangin and really leapt along. We had to wait a while for Rod’s depleted team to catch up. We felt the cold then.

We descended the Shambles Glacier to get a view of the high mountains of the Arrowsmith Peninsula. One could see down into the Leubeuf Fjord and I noted that the sea ice hadn’t formed yet. All information of significance as we now know the way to the foot of the McAllum Pass, which is but a day from Rothera Point, where we will be able to leave Adelaide for the south. We covered 17 miles today without great effort’

This trip continued in like vein and we took the opportunity to explore the main mountain range which afforded some spectacular views, but after ten days away, it was time to return.

From my diary:

‘Blew up most of the night and was still windy this morning. We suspect we had camped in a bad place and caught some sort of katabatic effect from the mountains.

We left camp at 1100 and had a great run back and arrived at base early after a 10 mile trip.

On arrival we found the muskeg and a fully equipped party all ready to come and look for us. This was due to the fact that we had been unable to make contact on two separate radio schedules due to the lack of signal. Made our apologies to Ian but explained that there was little we could have done in the circumstances.

Repaired a torn guy on my tent during the afternoon and in the process, managed to ram a needle, eye first into my palm. It went in about 2 inches and, as it wasn’t too clean, Terry gave me a stab in the arse (Penbritin) just in case. With the muskeg being ready for the field, we are off as soon as possible to resupply the depots at Lincoln Nanatak and The Pinnacle. Dave Hill and John Newman will accompany me and Rod.’

By the middle of April we were out in the field again, but this was far from successful due to the bad weather and we were forced to spend some days tent bound, with the wind blowing at 60 knots. With the wind came warmer temperatures and at one stage we experienced freezing rain alongside full whiteout conditions. ‘What a waste of six days this has been. All we have to show for it is an iced up tent and two teams of ice-encrusted and utterly miserable dogs.’

During this long lie-up, I had started to clean up and engrave a sperm whale tooth I had purchased in Port Stanley. The old seaman’s pastime had long fascinated me, so armed with a file, a bit of sandpaper, and a sailor’s triangular sewing needle I whiled away the endless tent-bound hours. Little did I realise that this seemingly harmless activity would cause me so much anguish.

From my diary:

‘When I awoke this morning, great lumps had come up on my arms, so after chatting with Rod, we decided we should return to base. It was pretty cold, -20˚C with a nasty wind from the south which made travelling very very unpleasant. Within minutes of leaving, beards were frozen hunks of ice and the cold bit cruelly into one’s face. Due to the swellings on my arms, I couldn’t fasten the cuffs of my sledging anorak, which resulted in my adding minor frostbite to my ‘new lumps’.

On arrival at the hut I felt physically ill, and my mood suddenly changed, as though a black cloud had descended upon me.’

For the next several days I felt really poorly. Terry diagnosed my condition as an allergic reaction to something – though he couldn’t determine what to. He thought it highly unlikely to be the penicillin he had given me, as the reaction time was too great. It was only years later that I discovered my ‘giant urticaria’ was most probably caused by my inhaling dust from the whale’s tooth, which I had rigorously filed and sanded in the confines of my tent.

It was all academic anyway, I was unwell for weeks and had to miss the next training trip as I was unfit to undertake such work. Fortunately, Ian Willey and Bill Taylor took the ‘Huns’ out, so while I missed out on the benefits of more sledging my dogs didn’t.

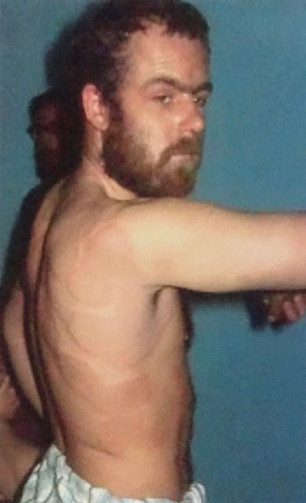

My condition deteriorated considerably during the period of the affliction.

From my diary:

‘My arms swelled up to gargantuan proportions, the crater like lumps joining together into a hard, swollen mass. Throbbing and aching all the time, there seemed no way of getting relief. Great puffs of fat appeared round my waist. My wrists and elbows and other prominences vanished. I had the body of a 20 stone slob. The antihistamine treatments that Terry assiduously tried seemed to bring no relief.’

Three days later there was little change.

I remained base bound until the end of May, when I finally got out again, on a last training trip prior to the winter setting in proper.

From my diary:

‘At last! Sat in a tent again with the wind attempting to stir things up. Steve, Rod and I got away by noon. With the onset of winter it’s no longer possible to travel before 1100 now. No difficulty getting off the base, as soon as the dogs were on the trace they were full of enthusiasm. It was ‘Up dogs, Huit’ and they were off like crap off a chrome shovel.

It’s exactly 37 days since I was last out in the field; a long time. My urticaria has gone at last, I’ve not had Phenegan for three days and not a sign of a lump anywhere.

Quite a nice day, temperature -14˚C and virtually no wind. We made good time, pushing on for 2.5 hours and covering about 9 miles. We discussed whether to carry on, but as it started to snow and we didn’t have enough time to reach Pinnacle Depot, we made camp.

The dogs went pretty well but Count played me up a bit near the end of the drumline, (markers to keep us clear of bad crevasses). He kept turning off course. I put this down to the low angle of the sun which was right in his eyes. A headwind with drifting snow didn’t help. We are using a three-man tent, all very cosy and comfortable.’

At this time of the year, travelling time is very limited, as it doesn’t get light enough until gone 11 and its dark again by 1530. The sun never appears above the horizon, just a dull glow to the north, with a slight shift to the west before darkness descends again. We made camp by the light of a Tilley lamp and packed up in the morning the same. Winter really is a bleak time at these latitudes.

We travelled as far as Pinnacle Depot in order to check that we would be able to find it, as we planned to make use of it at the start of our trip to Stonington in the spring.

From my diary:

‘The depot was intact, but two of the man-food boxes were buried in the snow. They must have been blown off the rocks. Rod re-stowed them, while Steve and I steadied the dogs.

On the way back, Rod went in front, suddenly he cried ‘crevasse’. We could see nothing, just undulating sastrugi. We gingerly moved forward to take a look. Jesus! I’ve never seen such a nasty hole, a lateral split, with just a few breaks in the snow both hiding and revealing a horrible rift. Peering in from the lip, it opened up like a great blue mouth, gaping and hungry.

The walls of this seemingly bottomless chasm glistened with an intense blue. Enormous stalactites of ice added the only beauty. It’s hard to place one’s feeling. A foot wrong and one of us could so easily have been through it. I’m writing this after time has passed and the realisation of ‘What if?’ burns into one’s thoughts.

I was acutely aware of the complacency that’s brought about by having travelled to this depot often. In one fell swoop one’s life could be over. It’s truly a hostile place for the unwary, even the places we have grown to look on as ‘our own’. The crevasse runs east to west about 300 yards off the Pinnacle, bearing 20˚ Mag from our camp to the Pinnacle.’

We returned to base for the last time on 4th June. No more field trips now until the spring. We had a fine run back, driving in close hauled to the mountains. At one stage, I stopped to wait for Rod to catch up. A great sight as he came snaking down in my sledge tracks, shooting across a windscoop with the light on his back and nine hounds in full flow. The whole team was enveloped in shrouds of mist, born of their own breathing, tongues lolling out, all full of life and the joy of running. The sky turned pink and spiral bands of grey and pastel blue streaked and spiralled over the mountains.

We learnt later from a radio schedule with Stonington that the ‘Picts’ and the ‘Huns’ were the last sledges to return to base before the onset of winter. We both felt confident we were ready.

We settled in for a month of darkness and cold, as we planned to set out as early as possible for our summer journey, and with this in mind we started to make our plans and overhaul our equipment in preparation. There was always plenty to do.

We continued to use the dogs round base for doing the dog feeds, and on one occasion, just to keep them used to being run we shifted almost 2,000 lbs of coal from the heap to the hut store. It was interesting shall we say, trying to work the dogs round the base. In fact, it was more for fun than work, as many came out to take part in what was really part of mid-winter hi-jinks. As one can imagine, with the permanent darkness, there were many extended ‘evening’ parties.

Midwinter’s Day or FIDS Christmas was spent in fine fashion.

From my diary:

A fine meal followed, really excellent, and lasting some two and a half hours. A nudie-film show caused laughter and finally a few beers. We ran a radio programme for those isolated at Fossil Bluff and Horseshoe Island. I went to bed relatively early, but at 3 am the ‘lads’ brought the folk group into my bunkroom.’

Rod and I took the ‘Huns’ out, wishing to give Barrie Whitaker a share in the outdoor sports. (He had injured his leg and wasn’t up to solo sledging).

Unfortunately the sledge tipped over and he ended up worse off than had he gone solo! After we had returned him to base, we went off the end of the jetty on the sea ice, but deep slush discouraged any serious wandering. On our return, we discovered that Kelly, who had been left on the span had slipped his chain, was severely ‘locked on’ to Rita. Resounding cheers from the lads drowning out the yelps from Rita.

On the eve of our departure I wrote:

‘Took all the boxes and the tents down to Stevenson Hut, as the base was getting littered with our travelling gear.

Bill and Steve have also assembled their gear, as they intend to accompany us up the Piedmont with the ‘Rabble’ (Base dog team).

All we need now is the weather to break and give us the chance to travel.

Bill Taylor wrote a will out for me and Willey is holding a copy in the base safe. It makes sense to do this as the monies that will eventually be bursting the seams of my bank account should be whacked out evenly.

Really looking forward to charging off the island now the daylight is returning. Within a few days we should be getting the sun with us for a brief glimpse each day. Spring is on its way and the whole prospect of the next six months is enervating.’

The morning of 5th July 1969 broke calm and clear. The temperature was a perfect -16˚C and at 1130 Rod and the ‘Picts’ and myself with the ‘Huns’ set off up the Piedmont bound for Stonington and as yet undetermined points south.

Ian “Curf” Curphey, GA – Adelaide 1969