On Thin Ice – Roger Tindley

During the Midwinter 1973 Falkland Islands Broadcasting Service record request programme, the Stonington Fids requested “Your Baby Has Gone Down the Plughole” for the Bluffers. This is the story of how such a request came to be made…

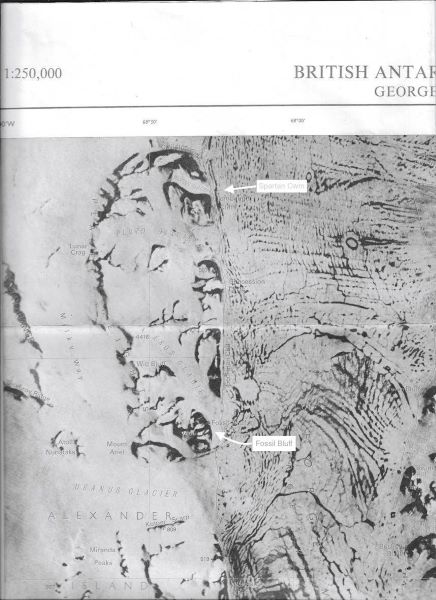

At Fossil Bluff we regularly used Muskeg tractors. They were used to establish large ice movement schemes, to re-supply our field station at Spartan Cwm, and to lay depots for dog teams and our own operations.

The Muskeg tractor was made by Bombardier Canada in the early ‘60’s. Intended for oil exploration in the north-west of Canada, it also served in mining and forestry. The Muskeg could be found all over the world, and there remain many working machines (including one at Fossil Bluff).

This engine was originally designed and built in huge numbers as a truck engine for the US Army in WW2. As you would expect, it was a tough and reliable power plant. However, it wasn’t the most efficient or economical of engines – in soft snow, hauling a couple of loaded Maudheim (large cargo) sledges, we would sometimes only get 4 mpg out of them!

In 1973 there were three of these tractors at Fossil Bluff – one built in 1960 which arrived in 1961 after an epic journey from Stonington that saw one of a pair lost after sinking in Marguerite Bay (the driver escaped unharmed.)

The following year saw another pair built in 1961 make it to Fossil Bluff, and thus we ended up with three to play with.

They were named: “Fred” – red, no driftproofing, just used around base and the airstrip; “Blodwen” – red and probably the best of the bunch at the time, and “Aphrodite” – painted a virulent yellow.

Spartan Cwm was an outstation of Fossil Bluff, where mass balance measurements – “is the ice accumulating or melting away?” – of the small but easily mapped Spartan Glacier were carried out. The cirque was on the Alexander Island coast about 25 miles north of Fossil Bluff. We had a single hut of about 12’ x 7’, comprising two insulated rooms – living space 6’ x 6’ and equipment space, about 4.5’ x 6’.There were two wind generators feeding into the battery banks, which powered 24/7 instrumentation that recorded several weather parameters, including sunshine duration and strength, temperature, wind speed, humidity etc. We took regular measurements of the dozens of snow stakes that had been drilled into the glacier ice, and made occasional forays up on to the mountain ridges surrounding the coire.

It was the most southerly of the network of such stations which were investigating ice, water, and energy balances of glaciers in a wide range of environments as part of the International Hydrological Decade (1965-74). These were the happy times when the world was unaware of global warming and climate change.

Andy Jamieson had previously set up and operated the next station to the north, situated on the Hodges Glacier, South Georgia. There was a very clear trend at Spartan Cwm. Four years’ data showed that Spartan Glacier was melting at an average of about 12” (30 cm) of ice per year over the whole area of the glacier, and at that rate the glacier would melt in about 500 years. It was even more apparent at South Georgia – the Hodges Glacier completely melted away by 2003.

We did regular supply and crew change trips to Spartan Cwm. Getting in and out of Spartan Cwm meant crossing the pressure ice at the bottom of the glacier where it flowed out to merge with the ice shelf of George 6 Sound. As in most of these areas, the movement of the Spartan Glacier combined with the tidal movement of the ice shelf resulted in pressure ice being thrust up into ridges and sometimes exotic shapes. Nothing remained static for very long, so there was no development of a permanent route – each passage through took a different route in the ever-changing ice topography.

In late April 1973 Andy and I had Blodwen towing a Maudheim cargo sledge which was packed with equipment and a skidoo. “Dougal”, our usually trusty machine, had decided he wanted a rest and refused to start. That meant we needed to use the muskeg and couldn’t do a recce the day before and we just had to find a route through when we travelled.

It had been a fairly late start but by early afternoon we had descended the glacier and were approaching the pressure. There were several flat areas which had probably been formed out of refrozen meltwater that was forced up as the two ice streams fought it out. Not exactly crevasses, any fractures in the pressure tended to fill up with meltwater at the end of the summer, and then this water would be expelled to the surface if the ice contracted. This was all fresh water, of course – the ice shelf at this point was about 300 feet thick, so no seawater was present. This meant that the expelled fresh water would freeze over quite rapidly, forming just the sort of flat surface that we liked.

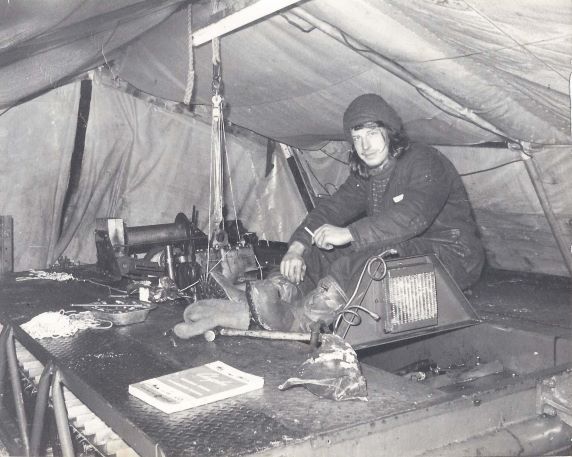

Andy went ahead with a bog chisel to have a bit of a poke at the surfaces and signal the best direction of travel to me. I was accompanied in the cab of the Muskeg by Rasmus, the Bluff husky – not for him the menial task of probing a safe route; the cab was warm and dry and if required he could advise me from the comfort of the adjacent seat.

As we moved on to a flat section of ice, something prompted me to swing open the cab doors to let me hear and see the surface better. I got a dirty look from Rasmus as a chilly breeze blew through our previously cosy cab. We progressed a few metres, but then suddenly the Muskeg gave a lurch to the right and the nose dipped towards the ice. I heard an unusual crunching sound followed by a further tilting to the right.

Muskeg drivers will remember the gear shifting system – two stubby levers between your legs, no synchromesh except from 3rd to 4th gear, and the propshaft whirling between your knees on its way to the differential. I downshifted into first gear to reduce the chances of the engine stalling and in the expectation that the track cleats on the right would get a grip on whatever was in front of them. But it was not to be. The tilt increased to the right followed by a distinct nose-dive.

It was time to leave – I gave Rasmus a good thump to get him moving out of the cab and let me out behind him. We both climbed over the seats and out of the left-hand door.

As I climbed out on to the crevasse plank over the still-turning left-hand track, it was clear that this wasn’t going to end well. The muskeg was gently driving forward as the engine idled in first gear – nothing would stop these long-stroke 4 litre engines – and I stepped gracefully off onto the ice as it quietly drove ahead into the water-filled hole it had created. There was a burst of steam and bubbles as the water reached the exhaust manifold, and a few seconds later, the engine stopped as the intake manifold flooded. It was suddenly very quiet.

It was a good job I had opened the cab doors – the tractor was wedged solidly in the ice and it would have been difficult to get out with the doors being held firmly shut. But there was no time to dwell on such thoughts – we had a complete Nansen sledging unit and skidoo on the Maudheim, so got them off quickly in case the whole lot sank.

What to do? Well, smoko, obviously. But at that moment a cup of tea was a longish walk back to the hut. I suggested we see if Dougal would start, so we humped him off the Maudie, I gave a tug on the starting cord – broooom! And so we didn’t have to walk.

We took the Nansen unit back up to the hut in the Cwm, had a brew and then put together some gear that we hoped would be useful. Returning to the scene, we drilled in a scaffold pole belay in the firm ice behind the tractor. The rear-mounted winch and its clutch control was still visible, so we ran out the wire and belayed her as best as we could. The Maudie was belayed as well, although the ice seemed solid enough (except for the spot I’d chosen to drive over, of course.)

Simon and Jim were thirty miles further north with the other Muskeg, Aphrodite, and we called them up, asking them to come down to the Cwm. Andy and I did some prospecting and found a route through for them about a mile north of where we had come to grief.

They arrived in the late afternoon the next day, leaving the caboose outside the pressure. We hooked up Aphrodite’s winch wire to Blodwen and gave it a good hard pull but there was no movement at all. In the gathering gloom and with snow falling we called it quits for the day and had supper together in the caboose.

There was much discussion on how to proceed before Andy and I drove Aphrodite up to the Cwm hut in the darkness later that evening.

The next day we were up and about early. We had devised a plan for a couple of belays, to which we attached snatch blocks with the winch cable reeved through:

When it was all assembled we had a five-purchase arrangement, which with the powerful winch on Aphrodite, proved more than adequate to snap the winch cable. The cable was old and rusty, and was roughly wound on to a small plain steel drum at the back of the tractor. The combination of old cable, tight bending radius and plenty of engine power meant that I had to take it easy with the pulling.

Another try and we parted the rope securing Blodwen’s towing hook to the winch wire, and she slipped further underwater. This was all very time-consuming as the day wore on. We made another few pulls to no avail before we twigged that she was still in gear, preventing the tracks from turning, which would allowing her to roll up and out of the hole. By this time we had all had enough and we called it quits for the day.

Day Three and it was a lot colder – ice had re-formed across the Muskeg-shaped hole in the ice. After some thought, we smashed the rear cab window, and after a lot of fumbling about, managed to depress the clutch pedal which resulted in a very satisfying lurch followed by a less satisfying movement further underwater. We set up a precarious arrangement – Simon perched on a plank, depressing the pedal whilst we pulled with the winch. Some movement but again we ran out of daylight and enthusiasm.

Day Four…the cold morning started with another hour or two of chipping ice. A mixture of brash ice, petrol and oil had been obscuring our view, but after we cleared it we could see that the rear of the tracks were wedged under a lip of ice. (The EP-80 gear oil floating on the surface soaked into my Dachstein gloves. Years later winter climbing in Scotland, I would catch a whiff of it and be reminded of our antics.)

After clearing the brash it became possible to probe around the gear levers and knock them into neutral. (The gear shifting wasn’t done with a “stick.” The clutch and gearbox faced forward from the engine, and Bombardier had simply extended the gear shifting actuating rods into a couple of levers. By depressing the clutch pedal with one bog chisel, we could select neutral gear with a second one, fumbling around in the icy water)

At the same time we attacked the ice lip with the bog chisels. Then we took one of the long planks from Aphrodite, shoved it under Blodwen’s arse and Andy and Simon bounced up and down on it whilst I operated Aphrodite’s winch. Jim was filming at this point, but joined the other two. With the added weight and leverage, she slowly came up and over the ice lip and back on to solid ice! We towed her up on to solid ice, and I set about filling her every orifice with antifreeze and oil.

Four very happy Fids had a celebration that night!

It was now nearing the end of April, and there was science to be done, so Blodwen was left freezing in the pressure whilst we four went off doing glaciology for the next few weeks.

On the 10th of June, a couple of weeks before Midwinter, Andy and I went back to Spartan Cwm with Aphrodite, loaded Blodwen on to a Maudheim sledge, and finally got her back to Fossil Bluff. She was winched up the ice and screes and manoeuvred into the scaffold pole and canvas shelter that constituted “the garage.”

During the following weeks Blodwen was thawed out, stripped down and rebuilt.

There was remarkably little damage done to the engine (I was expecting bent push- or connecting-rods, at least), and it was a good opportunity to service some of the areas that would normally be left until they blew up (clutch bearings and plates, universal joints, etc.)

Much of the electrical system had to be replaced, and the opportunity was taken to move the fuel tank from above the differential (where it prevented any maintenance being carried out) to an external position where it was also a lot easier to clean out.

Blodwen was back at work by the end of July, hauling several tons of equipment and depot material north for the summer 1973-4 operations.

Roger Tindley – GA – Fossil Bluff 1973 & 1974