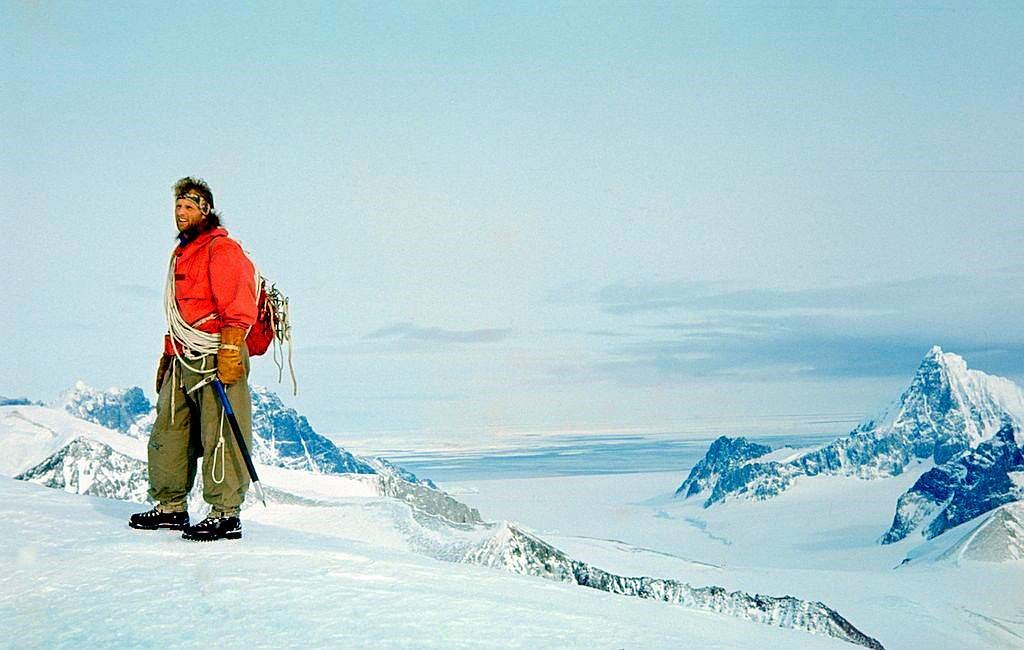

Stonington Island and the NE Glacier (Photo: Dave Matthews)

Our Return to Stonington – without Claire (continued)

Two men and two teams (17 dogs in all) were returning to base at Stonington at the end of a six months journey. For Claire, her last journey was almost over and she would certainly be retired if not put down before the next winter came. Already too old, this last gruelling day returning to base was proving too much for her, coming after 180 days on dried rations and over 1000 miles of pulling. We were pushing hard to reach home before a threatened spell of bad weather moved in, making this a day which eventually found its way into the record books. After thirty tiring miles with heavy loads in seventeen hours along the undulating surface of the Plateau, a brief rest to unload the sledges and leave a depot of all unused ration and dogfood boxes, then the prospect of a final 26 miles running light and downhill all the way. The younger dogs were still setting a fine pace, and impending bad weather did not encourage any further delay so after unloading, old Claire was taken off the trace and lifted on to the back of the sledge astride the tents and gear, where she tried to maintain her dignity – though drooping with exhaustion. The rest of the team would run too fast for her to keep up, when they had only light loads to pull.

Descending from the Plateau edge down to Stonington Island was a formidable undertaking at any time. This was Sodabread, described earlier. Four thousand feet of very steep often dangerously angled glacier – icefall really, and seeming quite impassable – down which the sledging route took a sinuous line into a huge natural amphitheatre (The Amphitheatre); culminating in the infamous Sodabread Slope, a straight 500 foot plunge down a gradient of around 1 in 2.5 to the valley glacier below. The dogs behaved well. These were teams and drivers who had been through a lot together and the dogs seemed to sense that it was an especially tense moment. The precariousness of the route was not the only danger, for this ice fall was notorious also as a breeding ground for bad weather and fierce storms which plagued the area; a natural cauldron where winds could build up in minutes to a strength which could (and had) at times meant death to men and dogs.

No sooner was the difficult descent started than tell-tale streamers of snow began to appear on the tops of the surrounding peaks and the wind rapidly increased to a local gale. It was hard to believe our bad luck. Less than a mile below us on the valley floor it was still a fine calm evening while at the Plateau edge we had difficulty in seeing our lead dogs forty feet ahead, through the rapidly rising drift. The snow surface was difficult to see too – almost a white-out.

By the time we reached The Amphitheatre, conditions were really unpleasant but this was no place to camp and wait for an improvement. As we turned left onto the long, narrow oblique line of the traverse, standing on the uphill runner of the awkwardly side-slipping sledges while at the same time trying to keep the foot brake hard on, we shouted a continuous Rrrr, Rrrr – left, left – to keep the dogs high on the left side of the traverse. To let them head too steeply down to the right would lead to almost certain disaster in the broken chaos of the main icefall.

Then the inevitable happened on the icy surface being exposed by the wind. First, one sledge tilted awkwardly on a small hump, slipped violently sideways, and then tipped over onto its side. For the driver this was always a nasty thing to happen and, even with a lightly loaded sledge, a problem to sort out. For the luckless Claire, it was the last straw. Thrown violently from her perch astride the load, she staggered to her feet, dazed and shaky and then set off up the slope, deaf to all shouts and entreaties. In no time she was just a white shadow in the drifting wilderness of snow; then she was gone. In moments, neither she nor her tracks were visible. ‘She has gone to die’, we thought. Searching for her was out of the question. There were other lives at stake now and with heavy hearts we turned our attention urgently to sorting out our own tricky situation, before it became seriously dangerous. With two teams and two sledges still to be extricated from such unpleasant circumstances, the complications and risks of starting a search for a single dog did not even bear thinking about.

Throughout the rest of that long descent there was no time to spare for recriminations. At the end of the traverse there were rope brakes to pull out and fit for the final hair-raisingly steep plunge to the valley floor. The number of turns of the rope around the sledge runners depended absolutely on the depth and consistency of the snow; getting it wrong could mean all sorts of trouble. Then, the moment of commitment. Like starting an abseil down a cliff face, there was no turning back. The whole team hung forward in their harnesses, their weight inevitably adding to the strain on the footbrake. The sledge hurtled downwards, almost over-running the dogs, and kicking up blinding clouds of snow from the ropes and the foot spikes. At last, just as men and dogs were at the limit of their endurance, the run-out onto more level valley glacier and, on my sledge at least, the ropes frayed to within one strand of parting by the icy crust hidden beneath the surface powder snow.

Now, after hours of intense effort and strain and with easier gradients and not too many crevasses in front of us for the final 20 miles, most of the tension drained away and there was time to relax a little and take in the grandeur of our surroundings. The wind howled impotently across the cliffs above and behind us, and while the sledges and skis hissed over a hard surface and the teams ran at an exhilarating speed through the long sunset of the polar summer night, we wondered about Claire. It was a dramatic way to meet her end. Perhaps she fell into a crevasse or perhaps she curled up and went to sleep in the storm. In either case, the end of a life but not without a certain sense of ‘rightness’.

After our safe return to base, the bad weather developed into two whole days of storm over the area, obliterating all our tracks and making us heartily glad not to be pinned down in our tents on the Plateau edge. Normally we might have kept an eye open for a stray dog to return; a young dog perhaps, returning over the sea ice where there was food in the form of seals and penguins. But an old dog lost in an icefall 20 miles up a difficult crevassed glacier with no food and no tracks to follow…… there was no point. Besides, there were all the delights for us of a return to relative luxury. A bath – if you filled the melt tank – and the rare experience of a whole year’s mail to read. The teams had to be settled onto their summer spans and fed fresh meat and blubber to bring them back to condition. So the days went by, soon running into weeks

It was five o clock one morning that several of us heard more noise than usual from the dog spans, but not enough to get us out of bed to investigate. The spans were a quarter of a mile away and there were over 100 dogs there. Probably an inquisitive penguin or something causing a bit of excitement. It didn’t sound loud enough for a fight or a loose team. Those of us who heard it, turned over and went to sleep again.

As luck would have it, the first person out of bed at the more normal breakfast hour was Jim. No-one knew Claire better and yet he hardly recognised her where she lay by the hut door in the morning sun. She could hardly stand up to be greeted or to accept food and she looked little better than a furry skeleton. She submitted to being fed a little and fussed over before turning away from us and giving in to a long, long sleep in the warm sunshine. The two of us, still blinking with surprise and emotion, crept back indoors to consult a calendar. It was eighteen days since that epic descent when we had lost her.

The story might have ended there. Claire took food only slowly and appeared to regain very little of her condition in the weeks following her return. It was decided that she had earned a chance to survive the oncoming winter at a more northerly base so she was retired to what was at that time the Antarctic’s closest approach to a rest home for old dogs, where she would be treated well and where she might be used occasionally for short recreational journeys.

One year later I saw her there and once again could hardly believe my eyes, such a sleek and contented-looking animal came to greet me. Only a trace of stiffness in the legs and a tinge of grey around the muzzle gave her away. By then she was eleven years old and few huskies lived to such an age in those days in that part of the world.

Our six month trip together was over, but it had included many shared moments of deep emotion and of course our share of tensions and disagreements. Jim was a strict disciplinarian in many respects, especially with his dogs, but usually it paid off.

I heard from Jim once more when he was back in Norway before returning to his adopted Canada. It was written on the headed notepaper of his family shipping business in Oslo and was already full of nostalgia for his time south. I realised then how little we knew of each other’s lives outside BAS. I knew that he had been a good skier (one major accident) and I knew that like me he was unmarried. My abiding memories of him are of an extremely able and competent mountaineer and skier, and of a trustworthy, reliable and rewarding companion and friend.

Dave Matthews – Geologist – Stonington – 1965 & 1966

Back to Stonington…