VP-FAP’s Demise at Gomez Nunatak – Mike Landy

I knew when I joined BAS in 1975 that aircraft operations in polar regions could be dangerous – finding a book in the Scott Polar library detailing dozens of US accidents before I set sail on the Biscoe made that plain. The Adelaide BC Steve Wormald deciding to hold a crash landing emergency practice without telling anyone (except our pilot Giles Kershaw) on my first flight into Adelaide from Damoy served only to emphasise the point. Still, my first season in the Peninsula as a glaciologist went smoothly enough and laid the ground for more ambitious fieldwork in the following year.

However the next field season didn’t start well in the Peninsula. In early September 1976 three Fids from our Argentine Islands base (now Faraday) lost their lives while returning from summiting nearby Mt Peary. Then on 15th September an Argentinian aircraft crashed on Mount Barnard, Livingston Island (South Shetlands) while surveying sea ice conditions, with the loss of all 11 on board. A helicopter attempting to recover their bodies was then lost, again with all on board. The dangers of work in the Antarctic were well and truly brought home. But of course you never expect it to happen to yourself.

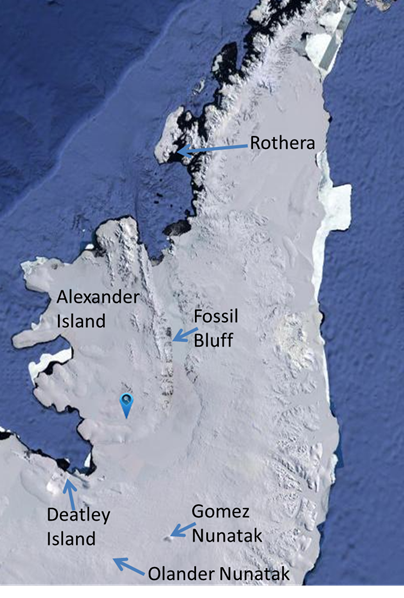

January 1977 found me working with GA Ric Airey and fellow glaciologists Richard Crabtree and Howard Thompson on DeAtley Island at the base of the Peninsula south of Alexander Island, undertaking ground borne radio-echo sounding of the island. The plan was then for Ric and I to fly to the remote Gomez Nunatak (75°57’S 68 38’W, altitude 8,500ft) 120 miles ESE of DeAtley to carry out six weeks of snow sampling and glacier chemistry in the region of the nunatak. An early attempt on 19th January to fly our unit to Gomez had to be curtailed due to cloud on the plateau, so we returned to DeAtley. On the morning of 21st January the weather was fine and the Peninsula plateau nunataks visible so the move looked on. Rothera told us to pack up ready to go and get back on air at 11:00, when we are told that Alpha Papa (BAS Twin Otter VP-FAP) is heading our way for pickup ~12:30. Our new Sledge Oscar will require several loads to Gomez, the first mostly fuel.

Conditions remain clear for Alpha Papa’s arrival ~12:40. On board were pilot Pete Prattis, air mechanic Bob Milburn and trainee pilot John Allan. The plan was to take the loads to Gomez, lay a depot there and then sledge to Olander Nunatak 65 miles SW of Gomez. Ric and John would remain at DeAtley whilst the first load was flown to Gomez and the aircraft then refuelled at Fossil Bluff. Returning to DeAtley, we would then pick up Ric, John and the second load for Gomez.

We were airborne with the first load at ~13:15. Within an hour Gomez was recognised and headed for. When we were ~15 minutes from the nunatak, Pete suddenly informed me that we were short of fuel and asked whether I preferred depoting the load short of Gomez, or returning for refuelling to Fossil Bluff before taking the load into Gomez. I opted for the former, and we landed in fairly soft snow. We offloaded and arranged the load into a depot. I took bearings onto Gomez and the Savin nunataks to plot the depot’s location, just under 20 miles from Gomez. We then flew empty to Fossil Bluff, needing to delve into the emergency fuel tank to get there. We refuelled fully and headed back to DeAtley, by which time it was ~17:00. We took on board Oscar’s second load, as well as Ric and John, and set off for Gomez at ~17:30. In my diary I recorded that, adding up all the cargo and personnel, the total load including fuel would have been ~6,600lbs; maybe this heavy load explained the long take-off and stall warning on leaving DeAtley.

Ric joined Pete in the cockpit, and I sat in the rear talking to John and Bob. When we appeared to be nearing Gomez I transferred to the front of the fuselage to see what was going on and find out where we were landing. I had suggested putting down at the depot short of Gomez and sledging the two loads the 20 miles to the nunatak while the aircrew returned to DeAtley for our last load but Pete decided we should land at Gomez and he would then move the depot back to Gomez if fuel permitted.

The altocumulus cloud bank ~5,000ft above the plateau, which during our previous flight had cast its shadow well to the north, leaving Gomez in sunshine, had now moved south and was covering the plateau till well south and west of Gomez (~20 miles), considerably reducing the contrast at Gomez. We looked for the depot and I sighted it at the expected spot – it was still barely in sunlight as we could see the aircraft tracks.

As we flew the remaining distance towards Gomez I remained at the entrance of the cockpit, next to the auxiliary fuel tank, in order to get the best possible view of it and the surroundings. We passed to the south of the main nunatak and over a smaller rock outcrop to its west then went into a steep banking counter-clockwise turn around the nunatak. I looked out of the port fuselage windows to get a good view of the nunatak – the only things that really registered were melt pools in the bottom of the wind scoop and the very flat lighting. I did not know whether, or if so where, Pete would attempt a landing, but after the first circle I thought we would circle the nunatak again to get a second look.

(Photo: Mike Landy)

I returned to look through the cockpit windows and realised that we had lost considerable height. We were aiming for the ~400m gap between the two rock exposures and from my position it was impossible to see any relief in the snow. I realised that there should be a slope in the gap but I could not gauge its steepness, nor could I see the outline of the ridge between the outcrops against the sky. However Pete seemed to be going into a landing attitude and I assumed that he was aware of any gradient we might be heading for.

Obviously he had not appreciated the steepness of the slope, but did so approximately 5 to 6 seconds before we hit the surface, for I saw him rapidly bring the column back and engage full throttle to return the aircraft to a climbing attitude in order to clear the col. However despite maximum power the aircraft did not seem to react; it simply shuddered and lurched while keeping the same attitude with respect to the slope. I vividly recall the stall warning sounding for around six seconds. The attitude of the aircraft was certainly that of rising, with the nose ski higher than the others, but the aircraft seemed to be flying flat in that attitude, with the fuselage parallel to the slope.

I realised that the aircraft was out of control and I thought that contact was imminent, so I moved backwards and to the left to avoid catapulting through the cockpit door. I shouted a warning to John and Bob who were sitting behind me on and near the skidoo. We must have hit the slope square and bounced before landing again on the fuselage and impacted undercarriage. No reverse thrust came on and it seemed to me that we were sliding for several seconds in that fashion, out of control and without losing much speed. The impact knocked me forward onto the cockpit wall and the auxiliary fuel tank to my left collapsed and started leaking fuel.

When we finally came to a halt I glanced into the cockpit to see Pete holding and shaking himself, having possibly hit his head on the controls, while Ric had already opened his door and exited. I was conscious of acrid fumes and my first thought was of a possible fire, but they did not last long and the accompanying haziness in the fuselage may well have been a product of the impact on me rather than real. As Pete did not look badly injured I turned back into the fuselage to see that Bob had opened the cargo door and jumped out, while John was standing in a daze, holding a badly cut and bleeding lip. Ric and I shuffled him out of the aircraft then, after ascertaining that no fire was alight or imminent, I did a quick survey of the damage.

We had come to rest on a ~15° hard-packed slope halfway between the main nunatak and its satellite rock outcrop. With the poor contrast Pete had thought there was a valley between the two and the higher col had not been visible in the whiteout. Both of the main ski supports had collapsed, the nose oleo and wheel were impacted into the nose of the fuselage and the bottom of the fuselage was on the surface, mangled and twisted. The various doors were either off their hinges or twisted slightly from the fuselage. All the skis showed structural damage, and the undercarriage had obviously taken the brunt of the impact. My abiding memory of the crash was watching red hydraulic fluid from the nose ski squirting out in spurts which gradually stopped, as if the aircraft was dying.

The immediate priority was to treat John, who was losing quite a lot of blood, but since it was from the lip there was little to be done until the flow eased itself naturally (he also said his chest was very sore – possible internal injury). The aircraft’s radio was dead so Ric (an experienced radio operator) found Sledge Oscar’s radio and set it up. He told Steve Wormald at Rothera approximately what had happened – time ~19:00. While he spoke to Steve, Bob and I started unloading the cargo and digging into the highly compacted slope to flatten off two areas for the pyramid tents. We then set up the tents, offloaded the skidoo, sledge and other equipment, and make sure that John was OK. Once the first tent was up I arranged the interior for two, got John in and left him in a sitting position with a brew, obviously in considerable pain.

I then went to the other tent and organised it for Bob, Pete and myself. By then it was after 20:00. We had a brew followed by scradge and took things easy. Ric and Bob gave a preliminary assessment of the damage and later I went to look at the point of impact in the snow. It was approximately 100-150 metres lower than where Alpha Papa had come to rest, and was essentially a large hole, approximately 1-2ft deep. The aircraft must have bounced around 20m before sliding into its final position. It was clear that this would sadly be VP-FAP’s final resting place. A number of photos I took of Alpha Papa after the crash are shown at the end of the article.

John was the only person with serious injuries and Ric made it clear over the radio that he needed medical attention, using the call-sign QSQ so as not to worry John. Pete was badly shaken and in severe shock – he had damaged his jaw and twisted his head on impact. Bob was also very shaken but otherwise OK. Ric seemed OK despite having hit the cockpit roof and my only wound was a scald from boiling water making tea. What I recollect strongly is the rush of adrenaline that accompanied those first hours after the crash, which helped us get the injured parties into shelter as quickly as possible.

What made our situation more difficult was the fact that BAS’s second Twin Otter was being rented out for the season to the US Antarctic operations based at McMurdo, 1,600 miles from our position. In addition we were ~500 miles from Rothera and the nearest other field party was about 200 miles north of us. After a fitful night’s sleep the weather was thankfully clear so Bob and I climbed to the top of the two Gomez rock exposures to survey the surrounding bondu for a safe landing strip. There appeared to be feasible sites both south-east and north-east of the nunatak, especially the latter.

Steve instructed us to minimise radio use so as to not drain its battery but at the planned 15:30 sched he informed us that Giles was on his way to us from McMurdo to pick up the aircrew and was ~70 minutes out. By then we had 7/8 altocumulus and the contrast was moderate to poor, so Ric and I set off with skidoo, sledge, P-bags and radio over the col and then north towards the region of smaller sastrugi. Thankfully the skidoo had started at first attempt. We went 1-2 miles before finding a suitably soft spot – here the sastrugi were much smaller than near the nunatak and a breakable crust had 4-5 inches of soft snow beneath it. We laid out a strip approximately east to west using cocoa powder from our sledging boxes, so that Giles could land into maximum contrast despite a northerly crosswind of 10-15 knots.

I skidooed back to the camp to pick up the aircrew, during which Alpha Québec made its welcome appearance around 16:30. Giles circled the nunatak several times before asking Ric to rearrange the landing strip north to south, then landing flawlessly. We speedily packed up the aircrew’s unit, lashed it onto the sledge and, with John on the rear of the skidoo and Pete and Bob on the sledge returned to the strip, which had been enlarged with some of Giles’s empty fuel drums. They were soon off around 17:00, leaving Ric and I to catch our breath and munch on some very welcome American field party roast beef and salad sandwiches. It turned out that Giles had been transporting an American field party of marine biologists when he got news of the crash. He turned around in mid-air and flew straight to the South Pole Station where he dropped off the poor scientists, refuelled and headed to us via another refuelling stop at Siple Station, a few hundred miles south-west of us.

Steve had asked Sledge Echo (geophysicist Les Sturgeon and GA Brian Sheldon) to sledge south along the plateau to join us in case aircraft access deteriorated and they arrived in the early hours of 24th January. Meanwhile Giles in VP-FAQ had evacuated other field parties back to Rothera. I was evacuated from the crash site to Fossil Bluff with Les on 25th January when Giles brought the two air mechanics to salvage as much of the aircraft as possible with Ric and Brian. They remained there until 16th February, working in temperatures down to -30C and strong winds, managing to return the engines, avionics, skis and fuel tanks to Rothera – quite a heroic effort.

On my flight back to Fossil Bluff we were fortunately able to spot the depot we had laid so we landed and loaded it onto VP-FAQ. I then spent until 16th February at Fossil Bluff with Les Sturgeon to provide weather scheds before returning to Rothera. It was interesting that I didn’t really feel the shock of the accident until I was back on base, when it finally hit me what a close call it had been.

What to make of the accident

It is always easier to see things with hindsight. The accident occurred because we arrived at Gomez hours later than planned, by which time the earlier clear sky had clouded over and any contrast had essentially disappeared. Pete had not refuelled at Fossil Bluff on his way to pick us up at DeAtley, so had to return to Fossil Bluff before we had even got our first load into Gomez. The aircraft was heavily laden and therefore less responsive in the final seconds whilst Pete was trying to regain altitude against a plateau down-flow. The slope and ridge between the two rock summits were impossible to discern in that lighting.

We were incredibly lucky that the aircraft’s attitude was roughly parallel with the slope when we hit, which meant that the undercarriage absorbed most of the shock. Had Pete tried to peel off left or right the result could have been disastrous. We were probably also lucky that the snow slope between the outcrops was rock hard, which meant that the aircraft ‘bounced’ rather than rapidly decelerate and possibly disintegrate. We were lucky that nobody was seriously hurt, though we weren’t sure of that at the time due to the possibility of internal injuries. We were very lucky that Giles was able to reach us within 24 hours and that the weather was good enough for him to land. That was a remarkable feat of endurance flying on his part. It was very unfortunate that everyone’s field season then had to be curtailed, including mine. Obviously the loss of the aircraft was a very serious blow for BAS.

(Photos: Mike Landy)

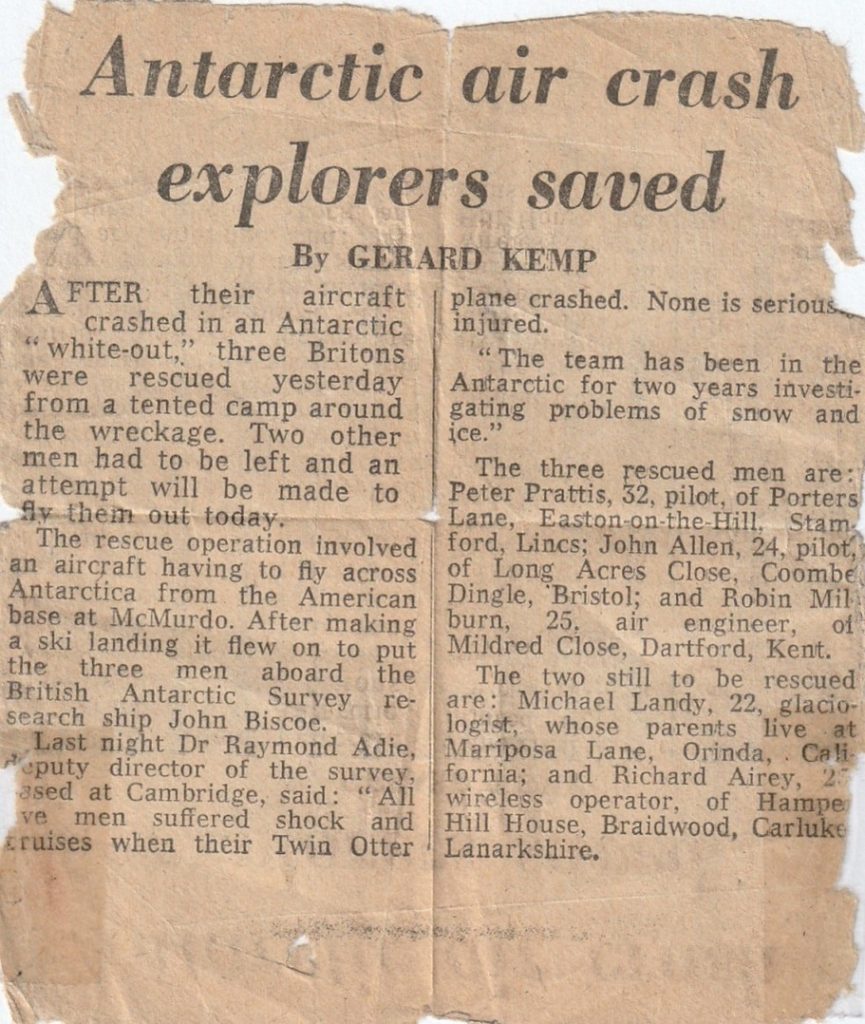

On return to the UK I was given two newspaper articles about the accident, from the Telegraph and the Express, both based on a press release issued by BAS – see them below. The accident was apparently also a major item on television news. The short Telegraph piece is mostly accurate, though describing my work as “investigating problems of snow and ice” felt rather wide of the mark. On the other hand the Express article hilariously excels in the number of mistakes it makes, even getting the hemisphere wrong. It certainly confirmed the old adage – never believe anything you read in a newspaper!

It is sad for me to think of the remains of VP-FAP encased in its icy tomb at Gomez. I was told by someone who had overflown Gomez a few years later that the tail of the aircraft could still be seen sticking out of the snow slope. At least we occupants on its last flight were luckier than those poor Argentinians earlier in the season. Luck of the draw…

With thanks to Ric Airey for filling in the picture, especially for the ‘aircraft salvaging’ days after I left Gomez.

Mike Landy – Glaciologist – Adelaide and Rothera, 1975-77

Addendum – The Props – Ric Airey

Given the place Altitude and Weather, this was a pretty fine effort too, marred only later by HQ ire that prop blades got sawn off!

At 8,500 feet and minus 30c in winds variously 25 to 60 plus Knots, what was achieved was grand and first time I ever got left with a box of spanners and a whole Airplane to Dismantle (it was fascinating and gave me a delight in the skills and wonders of the design and builders).

The Props were a casualty of our ignorance and exhaustion in the conditions; I had a long career in all marks of Twin Otter and in the days of single pilot it was my favourite flying pickup truck with many’s an hour spent doing my own maintenance and finding my way through the memory imprint of VP-FAP, whose main gear shock absorber block is my front door stop 45 years on – Bless the old Girl and Thanks for My Wonderful Life (that Last is the Words of a Pilot who taught us about Micro DownBursts).

He spoke the words as many test pilots have all the way to impact that we who came after could know and in Shackleton’s Way – “To Serve, To Strive , And not to Yield”

Like all accidents , not all injuries are visible. (Airmech) Bob M was seriously Freaked Out by the stall klaxon when landing VP-FAP; the well of courage is only so deep, go too many times and your bucket comes up empty:

Once in the safe proximity to Gerry at Fossil did not want to return to the scene: Hands Full Gerry could not be in two places at once:.

So advice was sought over the radio re: dismantling the prop blades, as whole they were just too big to stow, though Giles and I tried , even considered having the small side door padded and wedged slightly ajar, but No Luck so at least one blade had to come off.

Following instructions, (Brian) Sheldon and I tried to release the root hubs, indeed I snapped a chrome vanadium spanner in the attempt, likely the Cold Temperature had some part in the difficulty. The last instruction was if all else fails saw a blade off, so on we jolly well go; and the Mechs receive the bits box them up and eventually they arrive in Blighty or Canada, where (Paul) Whiteman has done a bang up job of selling them sight unseen as two dismantled props….

The receiver opens boxes and howls of pain flash over the wires to Whiteman, who Growls at the dept who forgot to tell him etc…. they Panic look for a Goat Sacrificial, preferably Dead or Departed,

Hurrah. Cue Ric! Departed dumb GA, obviously boxed up miraculously and never told anyone, and Big Round eyes, We Never told him to saw etc etc…

Big W, Cancels Ric’s Polar medal in absentia, While Chewing the Carpet etc etc. Ric “Happy to be of Service” Airey hears all this years later, and And Laughing Quietly realises the odd rude graffiti now understood

Bob M recovers his equilibrium and continues to good career without the LMC stamp in his service record. Gerry covers the paperwork cock-up with the excellent guile of a Master Engineer; Ric is Bomb proof cos he’s not there, so he can be the Heroic Useful Idiot of the piece:

But Memo to Accident investigators – and irate Accountants – Always Blame the Dead, as the living tend to object. Grin.