RRS Shackleton

Joining Shackleton for her First Voyage – Captain Tom Woodfield

I ran away to sea aged 14 after an argument with my mother. I only got as far as the railway station, half a mile away. Confidence ebbing, I conveniently let two trains pass without boarding them before my father found me. He worked ashore in the shipping industry and was interested in all matters concerning the sea, and he had an enduring love of mountain: and exploration; all of these he passed to me. He suggested that if I really wanted to be mariner, which indeed I always had, I should go to sea school first.

The Voyage of RRS Shackleton, 1960/61 – Peter Kennett

Recent nostalgic reminiscences about the ‘old’ RRS Shackleton prompted me to get out my own files and to wonder how many others might remember the ship in her grey days, i.e. before she acquired the polar red hull.

(Photo: Peter Kennett)

My first trip on the Shackleton, as a geophysicist was in 1960/61, and in many ways it was an exceptional voyage. I was following the pioneer work of Don Griffiths (Griff) from Birmingham University the previous year. Griff (who died aged 88 in October, 2007), had established a gravity base network and had begun a magnetic survey of the sea bed, which was later to contribute to the plate tectonics ‘revolution’. To build on his foundations entailed taking the ship to some outlandish places for landings with the gravity meter, which was quite popular, and steaming backwards and forwards across the Drake Passage, which was not!

Lowest in the Pecking Order – RRS Shackleton 1964-69 – Robbie Peck

(All Photos by Robbie Peck)

The first ship I joined was the RRS Shackleton in April 1964 in Stanley at the end of the season. David “Frosty” Turnbull, a New Zealander, was our captain. I had just turned 18.

I was a bit scared of him at first because he always looked at you as though he was going to go for you but I stayed with her, and him, until May 1969, when she was handed over.

I’d finished school in Darwin, well, truth be told I was made “redundant” from school after I floored the school gardener, who grassed on me. I’d been teaching one of the school master’s daughter how to drive and she put the Land Rover straight through the back of the garage us boys had just built as a carpentry project. At first, I thought I’d got away with it Read On….

Third Engineer on the ‘Shackleton’ – 1967-1968 – Ian Curphey

The scientific and support staff for the bases were all employed by the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) but tradition demanded that they were collectively referred to as ‘FIDS’, this being the acronym for the organisation that established the bases shortly after the Second World War – The Falkland Islands Dependency Survey. A disrespectful interpretation of this historical acronym was ‘Fucking Idiots Down South’.

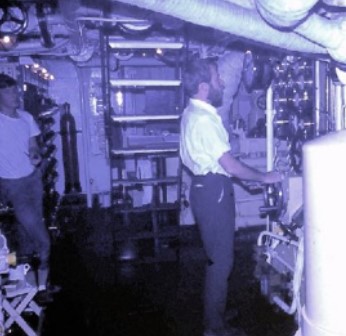

(Photo: Ian Curphey)

The RRS ‘Shackleton’ was the smaller and oldest of the ships operated by the British Antarctic Survey. The sister ship RRS ‘John Biscoe’ had the benefit of twin diesel-electric main engines, was larger and a bit more robust. The purpose of both vessels was to support the scientific work being carried out in various disciplines at the several British bases on the Grahamland Peninsula and to carry out oceanographic work independently, or in conjunction with the Royal Navy’s Antarctic Patrol Vessel, HMS ‘Protector’. The annual voyage of each ship lasted 6 or 7 months during which time the bases would be relieved and resupplied with essential stores and summertime building projects and maintenance carried out. The ‘Shackleton’ had accommodation for about forty passengers bound for the bases, in addition to the ships complement. The ships hold was packed to the gunnels with base food, dog food, spare parts, general stores, in fact all that was essential to ensure each base could operate successfully for the coming year.

The ship’s complement consisted of British Officers and mainly Falkland Islands crew as the ship was registered in Port Stanley, the seamen of those remote islands were born and bred Southern Ocean sailors, many of them having had experience on the whale catchers and at the whaling stations in South Georgia. From my perspective this arrangement could hardly have been better.

Easily settling into life at sea again we slowly edged our way south and west. We were bound for Montevideo in Uruguay where we would acquire bunkers for our Southern Oceans work. At our snail like pace of 11 knots we were at sea for 24 days. We arrived in mid November.