Flight Operations and Incidents with ‘Ice Cold Katy’ (continued)

(Photos: By Kind Permission of Jonathan Walton, from Kevin Walton’s book “Two Years in the Antarctic”)

Cape Keeler, a tongue of land known to the Americans during their stay in 1940, approximately latitude 60° 47’, longitude 63′ 15′ W, an estimated 150 miles from base, suggested itself as being another suitable point to establish a depot. “Two Ton Depot” 17 miles from base, sitting on top of the plateau, if revictualled by air and the volume increased, would enable the party leaving base, to make the 5000 foot ascent to the plateau with light loads thereby making for a considerable saving of time and effort.

‘Two Ton Depot’ was the first to receive attention and in this connection, Tommy in the Auster and Chuck Adams in the American Stinson L5 aircraft, had by 10 September 1947 airlifted sufficient to meet the sledging programmes. They had, in fact, transferred as much stores in three days, as it had taken us with several dog teams to sledge and haul the original cache of two tons, in three months: The next depot to be laid was to be that at Cape Keeler. The party nominated for this task were: “Tommy” Thomas (pilot), Bernard Stonehouse (co-pilot), and myself (surveyor) travelling in the British Auster aircraft, whilst Jimmy Lassitter (pilot), Chuck Adams (co—-pilot), Bill Lataday (photographer) and Ike Schlossbach (pilot and Captain of the American expedition ship), would travel in the Norseman (“Nana”), which would be the load carrying aircraft.

Of the respective aircraft, the British plane was very light, small, single-engined high winged monoplane Auster Autocraft (nicknamed “Ice Cold Katy”), powered by a Blackburn Cirrus Minor engine making for 96 HP, speed approximately 100 mph, ceiling 14,000 feet, range approximately 300 miles to dry tanks. The aircraft was built to carry two persons, i. e. pilot and co— pilot (or passenger) with a small area behind the two seats to accommodate up to 300 lbs, of luggage.

The American aircraft to be used was the Norduyn C-64 Norseman (nicknamed “Nana”). A cargo carrying single-engined aircraft, specially designed for cold weather operations, speed approximately 150 mph, range with extra fuel tanks approximately 2,800 miles to dry tanks!

The role of the Auster on this missions, was to accompany the Norseman for the purpose of reconnaissance, gaining knowledge of the first section of the sledging route to be followed, land first and check condition of the surface, select and indicate with orange trail flags the most suitable landing strip for the heavier Norseman and sketch and record prismatic compass bearings to locate the depot when it was laid.

For this exercise it was decided that in the Auster, the two front seats would be occupied by “Tommy” Thomas (pilot) and Bernard Stonehouse (co-pilot) whilst I (who was to be a member of the sledging party going South), would travel as a third member seated in the luggage compartment, with my back to the front seats and the engine. This arrangement meant that a incomplete emergency kit could be carried. This aspect was not overlooked, and it was agreed that apart from carrying the stores to be depoted a full and adequate emergency kit would be carried for both crews in the American Norseman. The possibility of parachuting both equipment and supplies in the event of such an emergency, was also catered for.

Basically, all was made ready for the operation by 10 September, but the weather at that time was quite impossible. There was continual cloud and a fierce blizzard blowing on the plateau for a period of 4 days. However, whilst we were having lunch on 15 September, time approximately 1330 hrs, Commander Finne Ronne hurried over from the American base to say that the weather was improving and opinion was that it would hold for several hours.

It was said that the Norseman could be made ready for take-off in a very short time. After the shortest of discussions, it was agreed that the operation should be prepared with all haste.

Since 10 September, all necessary preparation for the British aircraft, had been completed in readiness for a quick take-off and once the decision had been made, Tommy, Bernard and were airborne in a matter of twenty minutes. The first objective, gas for the Auster to make sufficient height to enable us to see clearly, the general weather pattern over the plateau and indeed beyond into the Weddell Sea on the eastern side of the Peninsula. Based on this assessment, so the Norseman would be advised by radio and the final decision made as to whether the trip should proceed.

The Auster reached the necessary 6500 feet in approximately half an hour, and was able to confirm that the weather was clear over the plateau and indeed, as far as one could see to the east and south. (To understand this procedure — one must realise that the weather experienced in the three areas of interest, i.e. at base, on the plateau and in the Weddell Sea, very often differed very considerably.)

The findings of the Auster were relayed to the Norseman on the ground, around which there was much activity making final preparation for take-off.

There followed a prolonged period during which the Auster circled above the base, waiting for the American aircraft to leave the ground, for it was intended that both aircraft should travel to Cape Keeler together. There were obviously problems, but reports from the ground continually said that take-off was imminent. With the passage of time, “Tommy” became increasingly concerned with petrol consumption, for we faced an estimated 250 mile journey, which with climbing, would require all the fuel we were carrying! With the uncertainties attending this operation, we obviously could not afford to continue this abortive flying indefinitely. The situation reached the stage when decision had to be made, as to whether we should cancel or proceed with the Norseman catching us up en route, or joining us at Cape Keeler itself.

With the sledging season upon us, we were most anxious that the much-discussed southern journey should be started as soon as possible and the Cape Keeler depot was a governing factor in the programme. That being so and the weather looking fair, decision was made in liaison with the Norseman still on the ground, that the Auster would proceed and if not overtaken, would land and prepare for the Norseman’s arrival. in this connection, it was, of course, much less hazardous for the light British aircraft to land on an unknown surface, than it would be for the heavier aircraft.

We were now on our way!

Passing over ‘Two Ton Depot’ and our Plateau Met Station, we noted the glacier which offered a promising sledging route to and from the plateau, and earmarked it for further reconnaissance. It may offer an alternative to that which we had used, known as “Bille Gulch”. We were blessed with a most impressive and spectacular view of the plateau looking to the south and to the many icebergs held in the grip of the frozen Weddell Sea to the west. It was another occasion when the vastness and incredible beauty of the Antarctic continent prompted a feeling of human insignificance and wonder.

Locating Cape Keeler was no problem, it was a conspicuous headland reaching out from the mainland for a distance of approximately 15 miles, The journey was uneventful, the weather was fair and spirits were high, but so far we had seen nothing of the Norseman aircraft!

Tommy set the Auster down on to the shelf ice, without mishap, just north of the Cape itself. The surface was found to be firm and but for limited clearing, offered a very reasonable landing area for the heavier aircraft, when it arrived. The most suitable landing strip was flagged with our small red trail flags, the heaviest obstruction removed and the smoke bombs made ready for firing immediately the Norseman came into view.

There followed a prolonged, puzzling, cold and anxious wait, for the time was passing and the weather began to look less settled. After about 3/4 hour, the American aircraft appeared flying fast and very high on a course taking it due south! A smoke bomb was ignited but hardly before the aircraft had disappeared from view, for landing reasonably close to the north side of Cape Keeler, meant that our view to the south was almost wholly obstructed by the Cape itself! What now? it was expected that after a short delay the Norseman would circle and return to where we were waiting, but with the passage of time and no sight of the American plane, we began to get anxious. From where we were, we could see the tell-tale snow drifts beginning to drift on the plateau and it became increasingly obvious that we would be stranded at Cape Keeler if we tarried too long. How long should we wait?

We delayed for about another forty minutes then to our surprise we saw the Norseman again flying high and fast, heading for base, and now, an “angry” plateau.

Let us at this point, leave the account as told by the Auster and return to the fortunes and sequence of events as experienced by the Norseman and base members, both British and American.

About thirty minutes after the Auster took off from base, word was received from “Tommy” Thomas, confirming that the weather was clear over the mile-high plateau, and indeed beyond and over the Weddell Sea. “Nana” the Norseman, had previously been loaded with food and stores ready for the depot at Cape Keeler, but there were still problems before the aircraft could actually take to the air: ice still had to be chipped off the main plane, the door had to be removed to enable the parachuting of supplies (if that proved necessary) and the proposed “runway” at base had to be prepared for “take off” by the heavily laden plane. The Amtrak vehicles (Weasels) were used to run back and forth to ”pack down” the soft deep snow. This being done and all other problems settled, “Nana” with Jim Lassitter at the controls, took off something like an hour after the British Auster had set course for Cape Keeler:

It should be understood that the two aircraft could not communicate directly with one another, for their radio transmitters were operating on different frequencies. Each aircraft could communicate with their respective bases and messages passed on as required, although in the case of the Auster, the small battery transmitter which it carried was very soon out of range and screened by the mountains of the peninsula.

The Norseman climbed to 7000 feet and crossed the plateau noting that cloud was forming in the North. Reaching the Weddell Sea, Jim Lassitter turned south to Cape Keeler. Not seeing the British party, he proceeded on further south to the next cape, which proved to be another 40 miles further on. Still no sign of the Auster! The weather began to thicken fast over the plateau and Lassitter decided that he would have to return to Stonington at all speed and radioed the American base saying “weather turning bad, but we will try and make it back to base. We have not seen the Auster”. On the return journey, the Norseman ran into cloud at 6000 feet with winds estimated as not less than sixty miles per hour! Weather and visibility continued to deteriorate; indeed, it was closing very fast behind the aircraft as it reached the base area. Without making any of the usual preliminary circuits to assess landing procedure, Jim Lassitter made the extremely hazardous landing without incident. The American flyers had been out for three hours and had seen nothing of the Auster. The time was now 7.00 pm and an Antarctic storm was upon us. As the evening and night wore on and there was no radio reply from the Auster (even though we knew the limitations of the radio they were carrying), great concern mounted for the safety of the party.

Commander Finne Ronne offered all American facilities to Ken Butler – leader of the British base, for it was now likely to be a search and rescue operation. Throughout the night, both camps in swirling snow and bitterly cold strong winds, loaded and prepared the two available American aircraft, to ensure that they were ready immediately it was possible to fly.

Respective engineers checked engines, refuelled etc., and Ken as radio engineer as well as Base Leader, installed a trailing antenna to ensure the very best radio reception. Dawn and indeed the next 48 hours, 16 and 17 September, brought continual fierce gale force winds, which, with the accompanying drift, made flying impossible. The two days were spent in reviewing, debating and planning the search which we hoped would result in rescue. All theories and possibilities were discussed, including:

a) “Ice Cold Katy’t had reached Cape Keeler, landed, had been missed by the Norseman, and as the weather deteriorated and as the crossing of the plateau would be extremely dangerous, had decided to “stay put”, hoping that the weather would improve later!

b) Had reached the prearranged rendezvous, had not been seen, had waited, then in spite of the deteriorating weather, had decided to make a bid for base, but had been forced down en route — but where?

c) The aircraft had come down with engine trouble, either on the outgoing or the return flight, but again where? (This had to be considered, but we had enormous confidence in David Jones our engineer and we thought this possibility most unlikely.) The aircraft had its 100-hour service only two days beforehand!

d) Had the aircraft crashed into a mountain?

The flight had been considered a local one and as previously recorded, only a skeleton emergency kit was carried in the Auster. It was obvious that the aircraft and crew must be found very quickly, for whatever the circumstances, with the passage of time the situation would be very serious indeed

. 18 September dawned bight and sunny but very strong winds continued. “Nana” took off at 0745 hrs with Lassitter, Adams and three from the British camp. The object being to traverse the route it was thought that the Auster would have taken in getting to Cape Keeler. (There was heavy overcast and Lassitter climbed to 7000 ft before crossing the plateau. Flying for thirty minutes due east over the Weddell Sea there was no clear space through which the aircraft could dive to lower levels and be able to see ground level. It was quite clear that the overcast and fog vent from 5000 ft down to the shelf ice. When it was obvious that nothing could be done, the aircraft retraced its route back to base.)

After lunch, Adams took off in the L5 and met extreme turbulence. He reached 7800 ft before attempting to cross the plateau which was still enveloped in fog and overcast. Having proved to himself that the situation for searching was quite impossible, he rerouted back over the plateau. When recrossing he was caught in a down draught, the aircraft losing height in an alarming manner. It plummeted to 6000 ft, but Adams was able to nose his way over the edge of the plateau, which was frighteningly close and so on down to base where the aircraft had to be towed by a Weasel to its parking place and lashed down for fear of it being blown away!

Again, late afternoon, Jim Lassitter took up “Nana” but was forced back by the very high winds and dense cloud. Throughout the day the drift snow on the lip of the plateau was blowing an enormous plume, thought to be several thousand feet into the air.

All in all a very disappointing day.

Next day, 19 September, Adams again took up the L5 for a 30-minute weather recce. On his return he reported that it was overcast and very high winds were blowing, but under the circumstances it was worth a try. Lassitter and Adams then took the Norseman (“Nana”) up over the plateau and thirty miles out over the Weddell Sea before finding a hole through which they could dive and come back in under the overcast. Starting back at Mobiloil Bay, they then began the first search possible since the disappearance of the Auster on 15 September. Working south the Americans combed the coastline down to Cape Keeler, then on to Cape Rymill and Hurst Island. Every area was explored as fully as was humanly possible, flying iov round all islands, mountains, and icebergs. After a 3-1/2 hr sortie, the Norseman returned to base. A sixty mile an hour wind was still blowing and here we were still without knowledge of the Auster and its crew. After this initial recce and in view of the appalling flying weather varying so much throughout the area of approximately 6000 sq. miles, which had to be searched, it was decided to set up a camp and base; one of the aircraft at a point on the east coast, in the area of Cape Keeler itself.

This was achieved that same afternoon, for Lassitter with an overload of 2000 lbs, “Art” Oven (American), John Tonkin and Douggy Mason (British) and food supplies for thirty days, made the journey and landed safely in a very suitable area. setting up base as programmed. It should be noted that very high winds were still blowing with visibility down to half a mile.

On 20 September, Chuck Hassage and Bill Latady (Americans) in a weasel, climbed Neny Glacier to look down Neny Trough, but they reported back saying that an 80 mile an hour wind was blowing in the Trough! Giving rise to dense impenetrable drift, so severe that field glasses could not be held steady to the eyes!

Next day, 21 September, The Norseman was loaded with additional supplies for the Cape Keeler base. Jim Lassitter and Chuck Adams with Kevin Walton aboard, first depoted the stores at Cape Keeler as programmed then carried out a search in the area of the Traffic Circle, Fleming Glacier and Neny Trough (plateau areas), all without success.

A week had now passed during which the weather had been very severe and the missing party was painfully ill-equipped. The search had been maintained as far as was humanly possible, but with negative results. The situation was now extremely serious and with the passage of time, there was a growing sense of despondency and an unexpressed fear for the worst.

22 September dawned bright and sunny, this the first day of its kind since the disappearance of the aircraft. Both American planes were airborne at first light. The Norseman (Lassitter) exploring north of Stonington base camp, whilst Adams in the LS was exploring the east coast and the plateau twixt the base camp and Cape Keeler.

Reviewing the situation, it could be said that basically the east coast and the plateau had been looked at south of Stonington to Cape Keeler, whilst the area north of Stonington had been subject to some scrutiny, but there was still room for a very much more detailed search, before it could be said that the areas had been covered adequately.

Maps had been kept indicating the areas and reliance which could be put on the search so far, and these were now getting filled up, but there was still much to be done. Opinion was still that the missing plane would be found in the Cape Keeler area and indeed, with the weather as of today, 22 September, being so fair, comment was made that “if we do not find them today we will never find them”.

Jim Lassitter returned to base for refuelling then took off again with full load, Art Owen (an American Eagle Scout), John Tonkin and equipment to operate from Cape Keeler for one week.

Let us at this point return to the Auster aircraft, which was left sitting on the shelf ice about Cape Keeler, waiting for the arrival of the American aircraft.

We had seen the American aircraft pass over us going south and again had seen it pass back again, this time heading for base. Decision was now made that we wait no longer but make our way back to base without further delay, however, before taking off we did make a final attempt to contact base on the radio, but as anticipated this proved to be futile. Apart from the limited range of the equipment, the 6000 ft plateau separating us from base, formed a formidable radio barrier.

The time was about 1830 hours and we could see the drift beginning to lift and plume over the plateau. There was no problem in taking off, but the weather blowing in from the north looked ominous indeed. A very strong wind was blowing and as we made height to cross the plateau, we began to feel its effect. Having reached a height of 7000 ft over the plateau proper, turbulence increased to a most disturbing level. The aircraft was buffeted with great ferocity and was subject to frequent air pockets with the accompanying up and down draughts.

Tommy did his best to maintain direction, but we were trying to battle against an almost head-on 60 knot wind and the Auster with its 90 hp engines was just not good enough to compete with this. It became increasingly obvious, that whilst we were making very slow progress across the Peninsula, we were at the same time being swept further and further south! The plateau topography was almost completely blotted out by swirling snow blizzard and glimpses of the mountain summits looked uncomfortably close. Tommy and Bernard in the front seats facing the route of flight, maintained a continual commentary on what could be seen (or rather what could not be seen). It was a commentary which helped to keep me “in the picture” for you will remember I was in the luggage compartment with my back to the line of flight and had a very restricted view of the outside world or would have had if the swirling snow had allowed it. The commentary also helped in assessing the situation and prompted thoughts of what action was open to us. Most certainly we were not going to reach base tonight! We had one very limited and indeed debatable clue as to where we might be and that was the briefest sight of a conspicuous mountainous rock which might have been that known to us as Black Thumb, this we knew to be approximately 50 miles south of base and here we were seeing it (or might have been seeing it), on our starboard side where as we should not be seeing it at all, or if we did, it should be on our Port side. It was about this time that I was violently air sick and that excellent lunch which had been interrupted for this operation was now lost at a most unfortunate time.

A tripartite discussion continued as to the pros and cons of the predicament in which we now found ourselves. What course of action should we take?

a) Attempt to land on the Plateau.

b) Try and get back to Cape Keeler.

c) Fly until we were as sure as we could be, that we had come over the Plateau and then attempt to land on the sea ice (if it was still there!).

The first two possibilities were dismissed as being virtually impossible. The third was hazardous but what else? Decision made, Tommy held as far as he was able to the most northerly course, but he had little or no choice, for the weather dictated the route! After another quarter of an hour, the topography seen in a limited way, suggested that we were over the edge of the Plateau and Tommy felt it safe to lose height and brace ourselves for an unknown landing on the sea ice, which we hoped was there to receive us and in a condition to safely accept a landing aircraft! Whilst no doubt Tommy and Bernard did brace themselves for the unknown, they did have the advantage of seat belts as well. I, for my part, had no such support, but pressed my feet hard against the rear of the luggage compartment and my back hard against the back of the two front seats. I cannot remember there being much said as we lost height. The aircraft gas still being thrown about, but certainly much less violently than as was our experience whilst over the plateau itself. Is bracing myself for the impact. had forgotten the discomfort of air sickness, my thoughts being centred wholly on our landing. With a good runway, landing in this Antarctic weather would have been hazardous enough, but was the ice there? Would it bear the impact, would we hit an iceberg, or a prowler held in the frozen seas, would Tommy have the luck of a clear “Runway

The last instruction from Tommy was “hold tight” . This we did and everything happened so quickly. It was only after the event that one understood what really took place. There was a severe “jar” then I found myself floundering on the ceiling of the aircraft, for we were now upside down! A momentary pause, then cries of, “are you all right switch off — get out”. Whilst we had not time to assess any minor problems, none of us appeared to be in any real trouble. The aircraft was on its back, but the doors were clear and free. Disentangling themselves from their harness, Tommy and Bernard were very soon clear of the aircraft. For myself, was also very lucky, in that with Tommy clear there was no obstruction other than his seat and was able to scramble out very quickly. The fear of fire soon subsided and we were able to take stock of the situation. Whilst we could not see it immediately, we were safely on the sea ice in an area where there were many “bergy” bits, i.e. small chippings of the ice cliffs or small pieces left behind by outgoing icebergs. These varied in size upwards of 5ft across. On making the blind landing, the starboard ski of the aircraft had struck such an obstruction and had broken off! The aircraft had turned turtle and broken its back. Propeller, main plane and tail unit, had all suffered severe damage. All in all, it was a complete “write off”. Of our personal being, both Tommy and Bernard, apart from a severe “shake up” had no immediate evidence of discomfort, whilst for me, I only suffered a bruised shoulder and ribs, but what luck and what might have been.

Visibility was very limited and there was a most unpleasant drifting of snow, but were spared the gale force winds experienced whilst over the plateau, We did not know exactly where we were, except that we must be south of base, off the west coast and from judgement of our glimpse of Black Thumb (if such it had been), we estimated that 80 miles separated us from a comfortable bed at Stonington!

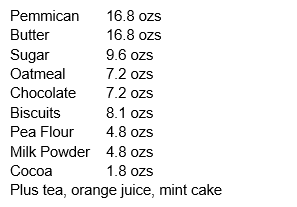

It will be remembered that we were not carrying a complete emergency kit. Our total survival food and equipment were as follows:

Of the three of us, Bernard was the most warmly dressed, whilst Tommy without a windproof was at a clear disadvantage.

For an understanding of the food situation the following would be the total normal sledging rations, per day, for a party of three men:

The time was 2025 hrs and it was agreed that we should camp the night and hope for better weather tomorrow! The radio was tried and effort made to contact base, but the radio had paid the price for the heavy landing. We found that it was possible to receive, indeed it was rather moving to hear familiar voices at base persistently calling us to “come in”, but we could not transmit.

Unfortunately none of us were radio experts. Of the three of us, Bernard was perhaps the most qualified and as such, sitting in the right hand seat of the aircraft, he was i/c radio. He worked hard and long to make the set serviceable, but without success and we eventually had to accept that although we could know what action base was taken, we would be unable to make contact and advise them of our position.

It continued snowing though the night and early morning saw the wind increasing considerably. Heavy drifting snow made for poor visibility and conditions were such that we were discouraged from making an early start, however as the morning progressed the weather improved and we eventually broke camp at 1200hrs.

We removed the aircraft fuel tank and using it as a sledge, on which we set two cine cameras and tripod, two cushions from the aircraft, wireless, receiving set, ‘Pup’ tent, two smoke bombs, petrol stove, cooking pots, our small can of petrol, pemmican, sleeping bags, ice axe, climbing rope and lengths of place fabric, we set out manhauling.

We still did not know where we were, except that the Base must be somewhere to the North of us. It was very hard going, for we were without snow shoes or skis and the snow was deep, but we persisted for about two and a half hours. by which time conditions had become quite impossible with an estimated 45mph cold head-on wind and drift. Tommy (Thomas, pilot) without a windproof was finding conditions very difficult and Bernard Stonehouse, co-pilot) volunteered his leather Jacket for Tomrny’s pullover. To this Tommy readily agreed and a change was made. We had covered a distance of what we though to be about three miles before making camp.

Further efforts were made to transmit on the radio without success, but we could still hear base calling us, indeed telling us that the weather was impossible for flying and for the moment no airborne search had been mounted.

We were all very tired and cold especially about the feet. We realised that we may have problems in this connection and each spent time in massaging feet and toes to keep the blood circulating.

Next day — Wednesday 17th September, we broke camp at 0835hrs. Visibility was limited but there was very little wind. Shortly after setting out, visibility momentarily lifted enough for us to see just where we were! We sighted Mushroom Island and Cape Berteaux. We were travelling about two miles off shore and parallel with the coastline. Our sight of Cape Berteaux told us that we were a little nearer to Base than we had at first thought. Out revised estimate was, that we must have come down about 65 to 70 miles from Base, as opposed to our original estimate of 80 miles. This was a pleasing adjustment and it was a morale booster to recognise specific points, for we no longer felt so isolated.

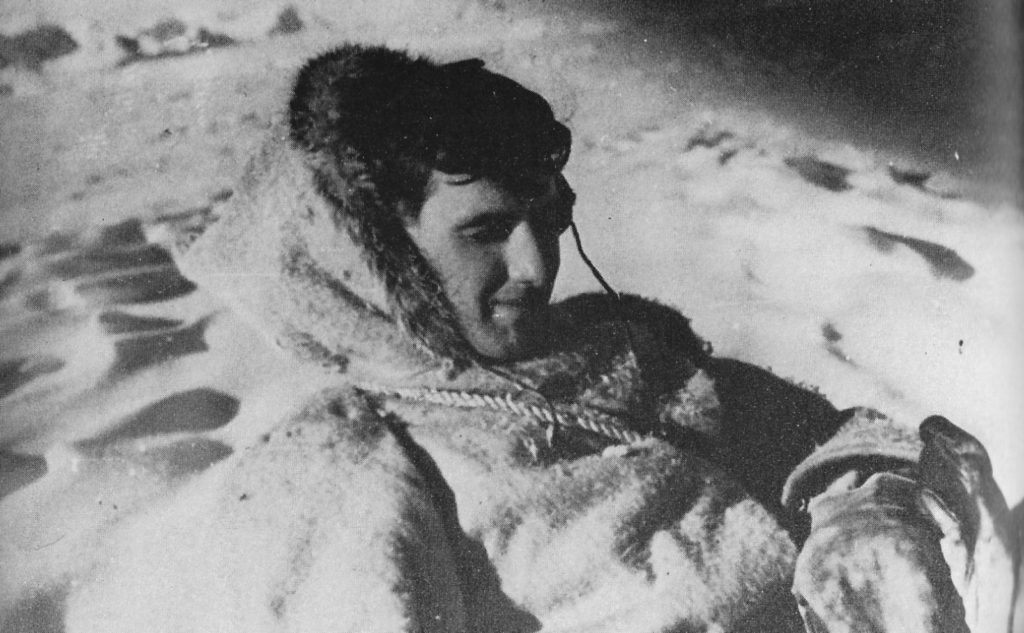

(Kevin Walton: “It is a salutory thought that these could well have been the last pictures taken of them alive had the sea-ice not held, or they had not been found by the American air search”).

We had trouble with the load shifting on the improvised “sledge” and frequently had to stop to relash with the limited twine available. The weather through the morning steadily deteriorated and gave way to fresh wind, driving snow and visibility again down to yards. However, after “lunch” at 1300hrs (a small knob of pemmican a little larger than a walnut in size) the weather in typical Antarctic style, changed dramatically for the better this time. Visibility lifted and we saw that which we recognised as being the island Terra Firma, seemingly very close. We slogged on, but despite better weather conditions, the going was still very heavy indeed. The soft deep snow making for a severe drain on our physical resources.

We were extremely tired by the end of the day — time 1740hrs. We were down to 10 minutes haul 5 minutes rest by the time we decided to make camp. We estimated that the day’s walk counted for about nine miles. A worthwhile contribution, but those nine miles certainly took their toll!

Thursday 16th September — After yet another very cold, wet, miserable sleepless night, morale rose in the morning for the weather started fine and clear. There was much sunshine, but the surface without the benefit of skis or snowshoes, was still atrocious.

We decided to “ditch” the “sledge” and indeed everything that could be left without jeopardising our safe return to Base. The dump was made, sketches drawn and compass—bearing taken to those conspicuous points available to us.

Whilst we were well aware of the curious optical effect as experienced in the Antarctic, due to the absolute clarity of the air whereby objects seemingly very close, prove to be astronomically further in distance, we elected to make for Terra Firma. The island was certainly a little to the West of the route we wished to follow, but it appeared to be only three or four miles away.

However, as was half expected, it proved to be a “snare and delusion”, We plugged away for two hours,- but the island appeared to come no closer At this we decided to change course a few points to the North.

We lunched on our knob of pemmican at 1250hrs, then carried on until 1750hrs, by which time we had covered an estimated 8 miles and indeed, we were still only level with Terra Firma! We were all extremely tired and needed our 5 minutes rest in between each 10 minute walk. We thought we heard an aircraft but certainly did not see one.

It will be remembered that we had a climbing rope. Having parted with the sledge, we agreed to “carry” it with us by roping ourselves together. We did not know for certain what was in front of us, but we anticipated having to climb over Red Rock Ridge at a point not crossed before and it was very likely that a rope would be needed. Apart from this, it kept us all together and should anyone break through the sea ice, there was some comfort in having a rope for support. Another agreement we had was that we should take turns in being the leading file, a position which also carried with it the privilege of wearing the snow goggles of which we only had one pair.

Of the other items we took with us, Tommy carried the small tent on his back, plus ice axe and camera tripod. Bernard carried one sleeping bag, petrol stove, some petrol and meths whilst I carried a sleeping bag, torch, smoke bombs, pemmican, prismatic compass, etc. The question might well be asked as to why we carried the camera tripod? The answer is that with the severity of the wind, the tripod with legs well splayed and veil “dug in” offered an anchor for a very welcome addition tent guy. When leaving the dump we filled the second of our two small pots with petrol and tried to seal it with medical adhesive tape, but, as expected, lost most the petrol before the first halt.

Being roped together had those psychological and indeed practical advantages which outweighed any inconvenience, nevertheless there were problems. To compete with the deep soft snow, we thought it might help to walk in single file, the man in front breaking trail, with those following behind making use of his footprints. Yes, it did help, but not so much perhaps as we had hoped, for with Bernard leading and to a lesser degree when Tommy was in front, I found it difficult to match their pacing. Both Tommy and Bernard were taller and had longer limbs than I. Of course the situation was reversed when it was my lot to be leading file, however we still thought it worthwhile to maintain the formation.

Another very cold, wet, demoralising night, during which having temporarily exhausted our immediate thoughts for our predicament, safety and problems, all to be faced again tomorrow, the very light fitfull sleep was punctuated by the imaginary sound of voices, dogs and music. This strange experience would no doubt, in the view of the psychiatrist, reflect in some way our mental worries and unspoken fears for the days ahead. Certainly we found time to think of our colleagues at Base, in some ways they would be even more worried than ourselves, in that whilst we knew that we were alive and well, they would no doubt be harbouring mental pictures of a ghastly accident, the whereabouts of which they did not know and were presently handicapped by the weather in making a wide ranging search. For us the situation was serious enough, but for those who did not know the facts, there would be a natural tendency to magnify all possibilities.

Friday 19th September we shivered our way through till early morning, when the weather prospects was rather encouraging. We broke camp at 0830hrs and with the surface conditions a little better than they had been the previous days, morale began to rise. Throughout the day we rested every ten minutes, for lifting our knees to compete with the deep snow — 2 to 3 feet deep — was so very tiring. It was still very slow going, but we were moving towards our goal. We saw a Snowy Petrel this morning, the first sign of life we had seen since leaving Base and it did something for each of us, in that here was another presence! A fragile but extremely beautiful bird, the sight of which had its effect on our thinking and morale.

We pressed on, running into an area of heavy brash and splintered bergs and as we did so, a very stong wind started to blow and lift the snow to make for a most uncomfortable swirling drift. We persisted, but Tommy without that windproof soon found conditions too much for him and camp was set up with difficulty at 1800hrs.

It should be recorded that at the start of our walk on the 16th, we had agreed that it was preferable that we kept close together and if anyone felt unable to proceed, he should say so. We did not think it time for heroics.

In spite of having started 9-1/2 hrs ago, estimated progress for the day was only 8 to 9 miles! Our estimate therefore, was that in four days we have walked for 30 hours and had cowered twenty nine miles! Not a very encouraging situation with still something like 40 miles to go. We were undoubtedly losing strength through the energy expended in competing with the knee deep snow and the continual cold to which we were subject.

Later we computed that we were working on 600 calories per day in comparison with the 4000 plus calories which was the normal sledging ration. Our feet were very cold and giving trouble, we had sore mouths and swollen cracked lips and were suffering from dehydration because we could not get sufficient water to drink.

In an effort to improve out lot through the freezing nights, we cut round the two sleeping bags so that they could be opened up and used as two “blankets”. A ouch improved arrangement for the three Of us, but they were so very wet that they were fast becoming useless. As with our clothes, they were first frozen stiff having suffered the elements as we walked, then thawed out in the early part of the night only to freeze again before morning! The problem having cut the bags was the cloud of older feathers which filled the tent. A very small problem perhaps in the light of the predicamentwve were in, but it was a situation I am quite sure we will all well remember.

The night of Friday 19th September was a repeat of the previous nights in that it was bitterly cold, wet and demoralising. Snow drifted and built up over the painfully small tent, which normally allowed the man in the centre to sit up straight (whilst the others could not), but now the weight of snow brought the “ceiling” right in on us! Another discomfort was the excessive “frosting up” within the tent itself, which resulted from three people being confined in such a small space.

Saturday 20th September dawned with the wind blowing very hard indeed, in fact too hard to consider moving immediately. We had a late “breakfast” and spent the first hours huddled together, all very cold and miserable, hoping and praying that there would be a change in the weather, but it just did not come. At 1300hrs, there was no sign of the wind abating, but we decided that in spite of conditions, we simply must try to get underway. It was most uncomfortable breaking camp, for we were all so very cold, but we eventually started off at 1400hrs. The going can only be described as being absolutely atrocious, the strong piercing wind full in our faces was “cutting us to pieces” and certainly Tommy was in trouble finding conditions virtually beyond endurance.

An estimated half mile was sufficient to promote very firm agreement between us; that we should stop and pitch our miserable “Pup tent” once again. The tent was re—erected under great difficulties and we each crawled in very much colder and depressed than before leaving it an hour before.

We had our precious brew of weak pemmican quite early, for morale had taken a “knock”. This cheered considerably for without expressing our thoughts, we all now began to view the situation with very much more concern. With the continual severe high winds, we thought more seriously of the sea ice on which we were now camped. There was now a serious possibility of the ice breaking up and us being carried out to sea!

As we lay closely huddled together with out ears to the ground, we could hear the tell-tale grinding and grating of the ice, as the wind and the disturbed sea played their part, and we were reminded of the experience of the American East Coast Geological sledging party, which had passed that way only two weeks before.

They had travel led parallel to, and half mile from the ice cliff, where the sea ice was two or three feet thick, but their route of march was punctuated by large areas where the sea ice had broken up and gone out, following which the sea had frozen over again, but at that time the ice thickness was only two or three inches! Indeed, on the morning that the support party was due to return to Base, their team of dogs broke through the block and had to be pulled and hauled out to safety. At the same time Doctor Nicholls, who was submerged up to his neck, but was able to scramble out before help could reach him. An extremely cold bath, but it served to remind him not to take liberties, for he should have been wearing skis or snowshoes!

Our progress had been so very poor that we yearned for a changed in conditions, primarily in the atrocious surface, which had been so taxing on our strength. Whilst it had been so very cold with such a strong headwind, we would, given snow shoes or skis (preferable the former), have covered perhaps four times or more the distance now to our credit, in other words we would now have been back at Base, having expended very much less energy!

The wind continued through the night and coupled with the low temperature, our wet clothes and wet sleeping bag, it was truly our worst night so far, in fact it was HELL! However, in spite of perhaps any private thoughts we nay have harboured, at least on the surface there was no doubt that we were going to get back to Stonington, and indeed get back under our own “steam”. we did not expect help from Base, for as we saw it, there had been virtually no flying weather since we came down five days ago, and we realised that the West coast would be the first area to be searched.

Sunday 21st September the wind was still blowing in the morning, but there was less drift, however we did not hasten to get out. The overburdened tent, now had two tears in the end used as an entrance. We had our very thin “breakfast” brew of pemmican at about 1000hrs after which we got Tommy, as one of the worst equipped, to get out and test the elements. This he did, but returned to say that he was quite certain that he could not face it! So followed another day of nil progress. The night was most miserable, continual shivering and it must be said, a certain lowering of morale.

Monday 22nd September saw dawn with the wind still blowing hard with impenetrable drift and we could not move. Re asked ourselves many times, “when would we get a break?” We were now getting very concerned. We had an estimated 35 miles to go, we were very cold and physically tired, our feet were giving trouble, we had wet aching limbs and I as custodian of the tin of pemmican had a keen eye on its contents.

We tried to sleep, but our physical well being, plus the thought of the ice breaking up under us and the worry of the tent which at this time had drifted up to about one third of its original size, all helped to make for an extremely uncomfortable and worrying situation. The wind persisted until 0200brs on the morning of Tuesday 23rd September when it subsided into an uncanny and unbelievable silence. A silence we had not “heard” at any time since the accident. We waited for ten minutes, then decided that if there was no other weather hazard, we would try and get underway. We crawled out of the tent which in itself was quite an exercise, for the tent was now down on top of us and we had to clear the drifted snow before we could move. We found the weather clearing fast and the temperature falling. Preparation was most unpleasant for our clothes were soon frozen hard, but with the weather improving and the knowledge that we would be cutting off more of those miles, which separated us from Base, our spirits began to rise. It would be a hard march, for the going underfoot was still atrocious. We were spared the blizzards of previous days, because the wind had dropped and the surface was frozen over, but it was only a thin crust letting down to deep snow and we frequently broke through.

We set our sights on Refuge Islands, an estimated 17 miles, for there we might get some refuge from the adverse weather if it continued. We saw our first seal in the half morning light. Here at least was food! I held its attention whilst Tommy detoured and came up behind to deliver a singly lethal blow with the ice axe. A quick despatch for which we were extremely grateful. Whilst we did not have the right tools for the job, we found ways of cutting into the creature and removing its liver, some of which Bernard immediately began to cook. We had very little petrol left for our little stove and this thought, coupled with the hunger which we were all beginning to feel, prompted Tommy to attack a portion uncooked! Bernard and I were content to wait until it was at least “par boiled”. This achieved, we enjoyed it, although strangely enough in spite of our hunger, we did not make the large meal as was anticipated. We soon lost our appetite. We cut the remaining liver, of which there was a considerable amount, into small pieces, filled our billycans then we set off again.

We stopped for a pemmican brew at 1300hrs having covered an estimated 10 miles (one mile per hour). The atrocious conditions under foot, found us extremely tired and definitely much weaker now, but we still aimed to reach Refuge Island although we realised it was no small task.

After “lunch” we started plodding our now very weary way, but after about twenty minutes, we were arrested by the sound and indeed sight of an aeroplane! Very great excitement followed, our weariness forgotten. Out with the precious smoke bomb which Tommy was now carrying, and out with the tin lids which we optimistically had to hand for use as helios if ever the occasion arose and, of course, if the sun was shining! A few dubious moments and accelerating heart beats, then it was apparent that we had been seen. The Norseman dipped, then quickly did one circuit before letting down gently to make a perfect landing in a very dangerous area, for there was much ‘brash’ about and as well we knew the snow was quite deep. The stout broad skis in the aircraft, served it well and the plane came to rest within 50 yards of where we stood. The extreme feeling of relief, as experienced by each of us really told us something of that tension and anxiety that was beginning to “take root”. Jim Lassiter was the American pilot with passengers Art Owen, American and John Tonkin from the British Base.

There was a round of handshaking and congratulations, all express with childish excitements again reflecting the mental reaction in us all.

It an occasion which will long be remembered by those involved. More and more chocolate and mint cake was thrust into our hands.

The plane was then emptied of all possible stores and equipment. John and Art undertook to erect a sledging tent and stay with the stores until being relieved later. The object of the arrangement was to lighten the aircraft as much as possible, for there was a big question as to whether the plane could take-off successfully. As it was, there were no problems, for although slow in gathering momentum, we were airborne without mishap.

By air, the distance back to base was estimated as being approximately 25 miles and this was covered very quickly and we were soon shaking hands with everyone we could see.

After the initial warm and excited greetings and the telling of the broadest details of our adventure, we turned to a still neat brandy, cups of hot sweet tea, liberal helpings of porridge, bread and butter, and then that of which we had all been dreaming ever since the 15th September; a nice warm bed and a deep sleep….

The news of our rescue and return to Base. was transmitted to the Governor at Port Stanley, to other FIDS bases and to all field parties where possible.

The news was, we understand, received with great relief and excitement. Quoting the diary of one: “Dave and I were in the tent listening to the BBC, whilst in the igloo next door Douggy was talking to Base on the radio, whilst Chuck Adams cranked the handled of the portable generator which supplied the necessary power to the transmitters.”

Almost at the sane time as the BBC announcer read the words, “aircraft still missing’, we heard the shouts from next door which were, “They are safe”. Chuck apparently forgot what he was doing and stopped cranking and immediately leaped up to shake Douggy’s hand, whilst David and I unashamedly wept for joy”.

Further quote from the diary of another: “There is no feeling quite able to describe the one that is in me tonight. It is more than relief for I know I had given up all hope of seeing them alive again. The word resurrection is part of what is in my mind”.

By evening, most of the field parties who had camped out at strategic points had been brought back to Base by the aircraft, for the weather was still reasonably fair.

To celebrate the occasion, Commander Finne Ronne invited the British Camp over to dine with the American party, where an excellent meal had been prepared by Sig. Qutenko (American cook). In the course of the evening Ken Butler read a message from the Governor to the Americans as follows: “I am delighted to convey to you the grateful thanks of the Secretary of State for the Colonies, for the unstinted help you have given in the search, so happily rewarded, for your three British colleagues. May I also add my personal appreciation and good wishes to you all”, signed Clifford, Governor of the Falklands.

The bed patients were not forgotten, Larry Fiske, the American Geophysicist bringing across attractive samples of the spread that was set before the party “across the hill”. The samples included steak, which had been buried in the ice since the Americans arrived at Stonington, months ago. Yes, it was exciting, but our desire for warmth and rest overrode all other earthly pleasures and whilst we were grateful for the thought and attention we received from our American friends, we hardly did justice to the exceptional meal set before us and we soon turned over to catch up on the last nine days.

Reflections and Conclusions

It is perhaps when reflecting and summarising in the comforts of the warm well run Base Camp, some days after the event, that one can understand and assess the situation quite dispassionately without getting things out of perspective.

It will be remembered that on the 23rd September, Jim Lassitter in the Norseman left Base with stores and personnel for Cape Keeler on the East Coast, but at the last moment he thought that he would fly south, down the west coast as far as King George the VI sound before turning East over the Plateau!

What luck for us!

Following our return to Base. the weather was as hostile and appalling as it had been during the period of our “walk”. There was continual blizzard for four days and the wind reaching gale force with impenetrable drift. In retrospect, although we had certainly not given up hope at the time of being picked up, it is very doubtful whether we could have survived in the conditions which followed.

One fear we had (previously recorded) was that of the ice breaking up and we being blown out to sea with it. In the days following our return, we noted (when we were able to see) that indeed “leads” had opened up in our “line of march”. Whether we would have been able to circumnavigate those leads, or whether we would have been swept out to sea we will never know.

Checking against temperature recording at Base during the period we were missing, suggests that temperature levels would have been in the order of 0 degrees Fahrenheit to minus 20 degrees Fahrenheit (52 degrees of frost). Not excessive for Antarctica but temperature level should not be confused with the wind chill which determines just how cold and uncomfortable one can be. Experience is that, but for frost bite, if one is suitably dressed, on can withstand extreme temperatures without undue discomfort, but if subject to even

a light breeze, a so called moderate Antarctic temperature can become very uncomfortable indeed. Once the strong winds set in, they tend to persist for a prolonged time and indeed present a formidable hazard to the Antarctic traveller, even when properly equipped and victualled. For us, we had experienced very strong persistent cold winds throughout our ordeal and -we were

not clothed adequately to meet the situation. To assist in competing with the cold winds, I tucked my survey field sheet under my pullover to keep my kidneys warm. (The record of work done previously was mutilated but not lost altogether)

.

Whilst repeating that confidence was high at the time Jim picked us up, we must confess that with each passing day we were growing more concerned and viewing the situations more seriously. Indeed, when breaking camp, early morning of 23rd September, we dreaded even more than we had done before, the very thought of spending more nights in the now almost useless tent. But for

the very high winds, we would have preferred to struggle in the deep snow than shiver and freeze in the bivouac tent. We had, in fact, decided (although it had been discussed before), that from then on we would try moving in the hours of darkness, for the lower nightly temperatures may make for better surface conditions. In making this decision, we would of course be hoping and praying that we would not miss a searching aircraft (most unlikely) during those hours of rest taken during the hours of daylight.

For me, my fingertips were very sore and two fingers were frostbitten, apart from which I suffered bruised ribs and a sore shoulder, which resulted from our “heavy landing”.

Taking stock of our physical condition, we were extremely tired and in need of long deep sleep. Apart from the cold and our thoughts which kept us awake, it was all so very cramped and uncomfortable. We took turns in sleeping (lying) in the middle, for that was the warmest place, but it was still debateable as to whether it was the best place to be, for while one’s companions froze on the side pressed against the tent walls, when it came to the frequent turning (as indeed we had to do in unison because of the restricted space), the “middle man” found the exercise very irksome and difficult.

We each wore Mukluks, which in the normal way were most comfortable footwear, but they were oversized unless worn with their quota of socks and duffels. I was wearing two pairs of socks which were inadequate for such a hike and in the course of the nine days continual wear, the Mukluks became very loose and “sloppy” with the soles turning sideways and upwards; so that I, and indeed both Bernard and Tommy who were affected in the same way I was walking on the side of the boot! This aggravated the condition of our feet for they were very sore having suffered badly through being wet and cold resulting in a condition of “Trench Feet”. Bernard was the worst off in this respect and was unable to walk for several weeks, whilst Tommy and I were free from any serious discomfort after a period of about three weeks.

We had great difficulty with our gloves for as with the rest of our clothing they were always wet or frozen stiff, a sequence that continued throughout our journey. We did not have sufficient fuel to thaw and dry them out thoroughly.

A fact which might puzzle some is that we were quite dehydrated through lack of water. When on the “march” we chipped ice off the snail blocks trapped in the sea ice, and sucked at it as we went along, but this was painfully inadequate and coupled with the high wind resul ted in thick swollen, sore split lips. You will understand that it was necessary for us to conserve out very limited fuel supply for making that very weak, but precious pemmican brew.

Being weighed on arrival back at Base, showed that I had lost 231bs in those nine days, but through many cups of tea and other liquid intake, I replaced 121bs in 24hrs.

Of our 71b tin of pemmican, which had been conserved so carefully, we arrived back at base with just under 31bs left, in other words, during “our walk”, ve had rationed ourselves to 2-1/2ozs per day! Normal sledging rations was -1/2%ozs per day, plus, of course, oatmeal, biscuits, sugar, butter, chocolate, etc etc!

After three days we each got up, but very soon sought the comfort of bed again, for we found that we were in a worse condition than we had first thought. Still very tired, aching and cold, however, Tommy and I were declared “fit for light duty” after three weeks, but Bernard’s recuperation took rather longer.

Final page typed up from Reg Freeman’s account of the accident and subsequent adventure involving “Ice Cold Katy” in September 1947.

Following such an accident we must stop, analyse and reflect on what we should have done or should not have done. What was lacking in our preparations and what we would advise others. There were certainly areas we could criticise ourselves but perhaps the main areas were:-

Lack of respect for the Antarctic weather.

Division of emergency stores and equipment twixt the two aircraft.

Inefficiency of our radio.

Lack of snowshoes or skis in our emergency equipment.

We should have considered more carefully what clothes we were wearing.

Proceeding on such a mission so late in the Antarctic Day. We knew of, and indeed had considerable experience and knowledge of what must be coldest, windiest, most hostile, unpredictable, treacherous, changeable weather in the world – but we still gambled on it! One is bound to reflect on the unstinted help given by the Finn Ronne Expedition and the particular parts played by pilots Jim Lassiter and Chuck Adams, in a modest and efficient manner, who displayed great skill and courage, flying in the most hazardous and dangerous Antarctic conditions. In doing so we must remember that they were using up their precious fuel which was essential to their programme and success of their mission.

Of my Colleagues, both “Tommy” and Bernard proved to be the very best for such a taxing ordeal. Always displaying initiative, patience, understanding and spirit. Cheerful – yes, although it would be less than frank to claim that humour was a strong point during the last few days of our walk, in fact conversation generally was restricted.

It was agreed that I, as the oldest of the trio, would assume the role of “chairman” in any discussion or debate, holding that casting vote if it was ever required. (No such situation arose).

Physically, I humbly believe that I was perhaps the strongest, whilst I was of the opinion that Bernard might be the first to find things impossible.

Happily, although circumstances were severe, these possibilities were never put to the test.

Typed by Jonathan Walton, from a copy of this report found by Jonathan in Kevin Walton’s archives – November 2020.