A Fid – with No Camera! – Roger Scott

8th January 1974 – 1315 hrs. During the summer survey programme we were travelling north up the western side of the peninsula and had just crossed from the Seller Glacier to the Airy Glacier at around 69º 15’ south. My diary records that we had slept through our morning alarm (a bad omen?) but it was a fine day with good sledging surfaces. I was leading with the Vikings but as we moved across onto the side of the Seller Glacier the surface deteriorated and became very uneven and lumpy. This is not easy to travel over wearing skis so I had taken them off, stowed them on top of the sledge and continued on foot alongside the sledge.

Continuing from Home Page & Stonington 1973…

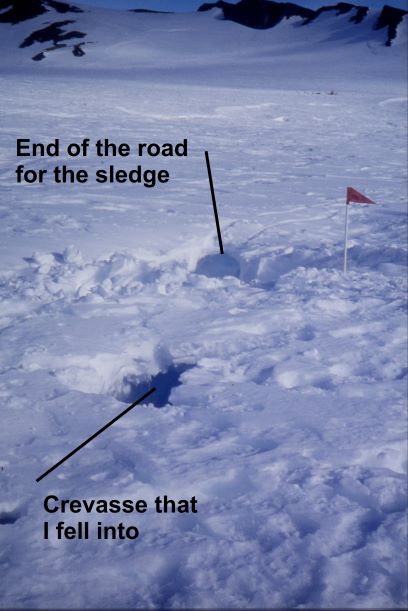

We were going at a good pace, maybe 3-4 mph so I had to part run, part walk to keep up. I remember that the scenery was fantastic, it generally is travelling on a glacier, and with the fine weather and good views and maybe I was not concentrating as much on the terrain as I should have. The next moment, whoooofff. a big noise and I saw my sledge fall away from me into a crevasse. I leapt out to the side, ran a couple of paces, and fell into another smaller crevasse. I was left supported by my arms with my lower body hanging in free air. I just managed to extricate myself and stood in one place surveying the scene. My sledge was nowhere to be seen but fortunately all the dogs were on the surface. The main trace between the rear pair of dogs and the sledge had snapped. The dogs were a bit stunned and surprised, realising that something had happened and they were not moving. Two of them had broken harnesses and it says something for the strength of the dogs that they had taken the strain as the sledge, weighing probably around 750 kgs, had fallen down the crevasse.

My sledging partner, Neil McAllister, was now coming up behind and brought his team to a halt about 20 metres behind me. Using his crevasse probe we did a quick check of the area to determine where it was safe to walk and then collected my dogs and fixed their trace. On investigation my sledge was wedged upside down about 25 metres down in the crevasse where it started to narrow. As the sledge had fallen into the crevasse the main trace had cut into the softer side of the edge of the crevasse and then tried to pull the dogs down as well. There was enough resistance in the whole team to withstand the increased tension of the fall and the rope snapped. I was very lucky as the sledge could have quite easily have pulled the whole team down into the crevasse.

When travelling in the Antarctic two sledges always travel together and each sledge will be loaded so that if one sledge is completely lost then survival would still be possible with the contents of the other sledge. Man food and dog food is divided out and if one sledge carries the regular main pyramid tent the other sledge carries a small two man mountain tent. It was mid-summer with 24 hour daylight so we had plenty of time to set to work on the recovery. Neil stayed on the top and I then abseiled down to see what damage had been done. Supported by the rope I was able to reach the sledge and then had to carefully release the individual items one at a time. They would then be pulled to the surface by Neil. I had hoped to get some photographs of the recovery but the only large item I could not find was my sledge bag, attached to the rear of the sledge, and this held all my personal items including my two cameras. Finally I had to get to the surface and used my two Prusik loops. We always carried two Prusik loops in our pockets for emergency situations and for the first and only time in the Antarctic I had to use my Prusik loops to climb a rope. (A Prusik loop is a short loop of thin cord used to attach around a fixed rope and is used in climbing as a simple alternative to jumar clamp which could not be carried in a pocket). My diary then records that we had everything on the surface by 2000 hrs and then travelled another half a mile to a campsite.

The next day was spent taking stock of the situation. My sledge had suffered quite a bit of damage and apart from my sledge bag there were quite a few smaller items still missing. Fortunately the weather was fine and after recounting my problems the previous night on the evening radio schedule a plane was able to fly in with spare parts. At midday after collecting the spares we set off again for ‘the hole’. I then spent about 4 hours up to 30 metres down searching and shovelling in every nook (and cranny. I had found everything except my ‘thumper’ (for controlling the dogs in a fight) and sledge bag and had virtually given up hope when suddenly I came across a piece of canvas sticking out of the snow. My sledge bag was completely buried under a block of ice about a metre square. This was far too heavy to move so I set about breaking it up with my ice axe. With the sledge bag recovered I climbed once again to the surface and spent a happy evening sorting things out.

The next day was devoted to sledge repairs and after about four hours work I had completely replaced the rear end. Not quite as good as new but substantial and good enough to get me through to the end of the season. The beauty of our Nansen sledges was that they were almost entirely constructed of wood (ash) with bindings of either cord or rawhide. A sledge could be almost totally rebuilt in the field with no need of any tools apart from a knife.