On the 7th February, after an extensive period of cargo work at Stonington and Adelaide bases, the John Biscoe headed for the Jones Ice Shelf which in 1972 occupied the Jones Channel between the Arrowsmith Peninsula and Blaiklock Island. It has since disappeared. The aim was to cull around 400 seals for the dogs. Killing that many animals when I had never killed anything in my life was a bit hard to take initially. However, the BAS scientists told us that it helped keep the general seal population at the right level. Also, there was a scientific need to measure the seals and take various body part samples (I won’t go into which) for study later by BAS. Sealing activity took place in between other base relief activities such as general cargo work. Here I have focused just on the sealing. When we arrived at the ice shelf late in the morning there were around 200 – 300 seals, mostly Weddells and Crabeaters.

After lunch the shooting started. This was done by the crew quickly and humanely and then we joined them on the ice shelf to begin our journey along the dog food chain.

After watching the experts, I did get to gut my first seal but initially the removing body parts for science bit I couldn’t cope with for some reason.

It was so sunny and ‘hot’ that most of us were stripped to the waist. Gradually more and more seal were dragged to the edge of the ice shelf ready for loading on the ship. I was quite surprised how little the general scene bothered me.

It became clear that sealing was a very necessary activity to keep the dog population alive and healthy. Unlike civilised society where you go to the butchers for meat, we were cutting out the middle man.

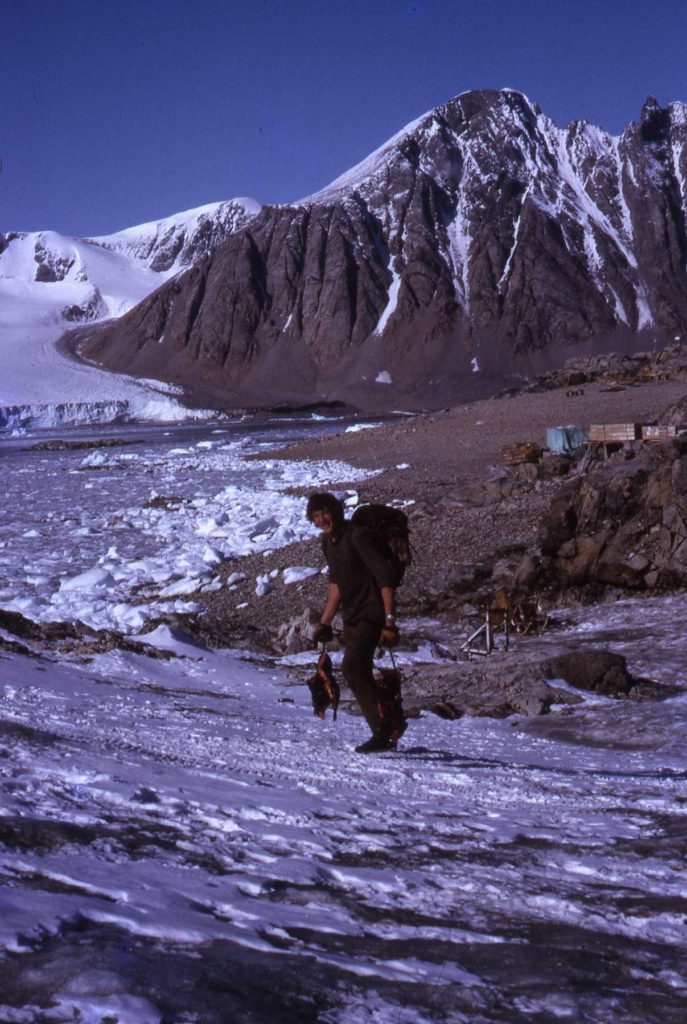

The next day strong katabatic winds resulted in most of the seals leaving the ice shelf. So, the John Biscoe set off for Ryder Bay on the southeast coast of Adelaide Island to continue sealing. I was still a bit uncomfortable about certain aspects and so opted out for the day by doing gash for one of the other FIDS. There was a benefit to this. It also meant I could take some hassle free photographs which was a good plan until four people asked me if I would take pictures for them using their cameras.

The cameras were all different so it was quite a challenge but I managed in the end. Next we sailed back to Stonington but a period of high winds delayed offloading any seal for a few days. We started unloading the most evil smelling festering seal on the 11th February which wasn’t my most favourite job in the world. The next time seals were on the agenda was some time later on 16th February when we sailed back to Ryder Bay. I was mainly on the scientific team measuring seals etc. and by the end of the day we had loaded around 50 for the dogs at Adelaide base. One of the crew gave me a lesson in knife sharpening, something that would serve me well over the next two years. The trouble free unloading of this batch of seals occurred the next day before we sailed back to the Jones Ice Shelf.

So, on 18th February we were anchored and set for yet another days sealing on the shelf. I was again detailed to do scientific work so most of the time was spent measuring seals. The highlight of the day was bagging a large leopard seal on one of the ice flows. Needless to say the skin was in hot demand and soon taken.

During all of this we did have the odd FID who conscientiously objected to the whole sealing operation and today was no exception as he yet again refused to do anything. Needless to say he wasn’t recruited to work in the field with the dogs which was just as well. Most of us by this point had fully accepted the need to hunt seal and had even embraced the smell. After anchoring close to Horseshoe Island for the night we sailed back to Stonington the following morning and by 9am were ready to offload seals again. The weather was a bit manky but as the wind increased the scow ride with the seals became pretty desperate. In spite of having on all my waterproofs I still got rained on by seals blood as they were lowered to me waiting below in the scow.

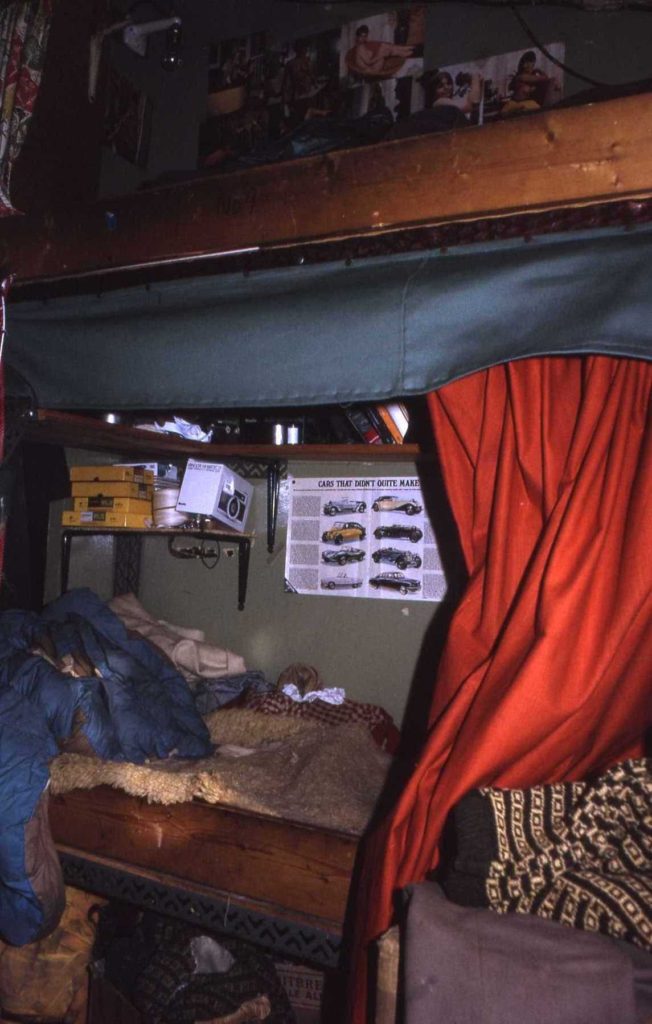

This was not a great day because I also got landed with the last scow when everybody else had disappeared. As a result I was late for tea on board ship and having had no time to shower ate it while stinking of seal. That day the base FIDS came on the ship to watch a film while us new FIDS took our gear to the base with the exception of the conscientious objector who chose to stay on board. That night I slept uncomfortably on a wide shelf by candle and Tilly light in what we used to call the hotel (the old American base). This was only temporary though and I did eventually get a proper bunk on the main base – luxury! This is where I switched from ship FID to base FID.

Having landed all the seals, the next job was to get them stored safely so they could be accessed during the winter. Some were stocked in the derelict building (known by us as the seal store – no prizes for that name!) next to the hotel and the rest right on top of the island where drifting up would be relatively minimal. In 1972 this job was carried out by teams of FIDS man hauling but later in my final relief in 1974 we had an old Land Rover to do the job.

I did quite a bit of hauling over the next few days and because I was now a base resident I started to chop seal and feed my dogs, the final part of the dog food chain experience. We did the chopping in small teams. The 24th February was a typical example with 3 of us, Miles Mosely (GA), Rob Collister (GA) and me working together.

This is where the sharp knives and axes come in. During the winter especially, and at other times when the weather was bad, seal chop mainly took place inside the seal store. In winter, because the seals were frozen we used chain saws. I’ll never forget the first time I did this. Nobody told me about the fowl smelling minced meat that flies out of the back of the chainsaw. My over trousers were plastered in it.

Dog feeding took place every couple of days and was generally carried out by each team’s driver. As with all the teams, feeding the Ladies generally involved filling a smelly old rucksack with big lumps of seal and carrying them up the ice ramp on to the North East Glacier where the dogs were spanned. This could be quite hairy especially when the ramp had glare ice on it. However, it was great to see the dogs tucking into their dinner and feeding them helped bond drivers to their new found friends. So at this point the dog food chain was complete.

This concludes my account of the first experience of sealing and the subsequent tasks I had to do along the dog food chain. Each year sealing was the responsibility of the incoming FIDS and the crew of the ships. So, I never got to experience it again after the 1972 relief. Although later, we did bag a stray seal that had wandered onto the island; great for our Sunday lunch! It was very nice too; tasted a bit like very rich beef stew as far as I can remember. Sealing was not talked about very much back in the UK when I was recruited and briefed. Most of the slides I was shown by old experienced FIDS were the usual beautiful Antarctic grips. So, no wonder I was shocked initially. However, it was a big part of our lives on base and I soon realised it was very necessary and yes, it didn’t take long before I smelled as bad as that first smelly FID I met on the John Biscoe at the start of Stonington’s 1972 relief.