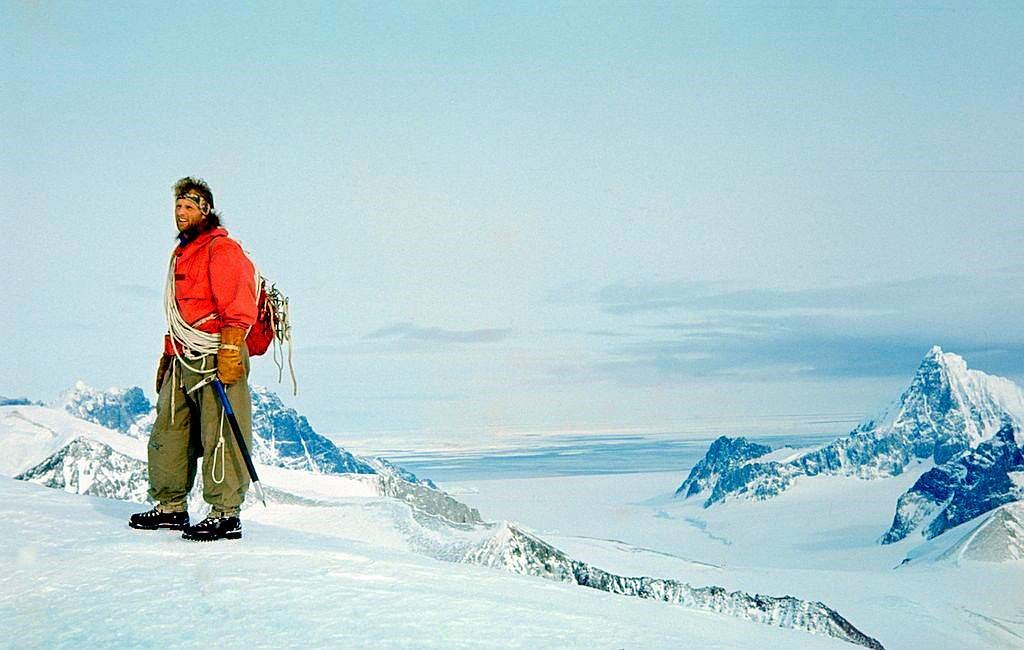

Mount Rendu and Blaiklock Refuge

(Photo: Malcom McArthur)

FIDS Exploration in Northern Marguerite Bay

Multiple Authors – Edition 1

Where to Start….?

Most of the effort during BGLE, RARE, USASE and Fids prior to 1948 had centered around exploration to the south of Stonington, along the Palmer Land Plateau, the East Coast and to Alexander Island.

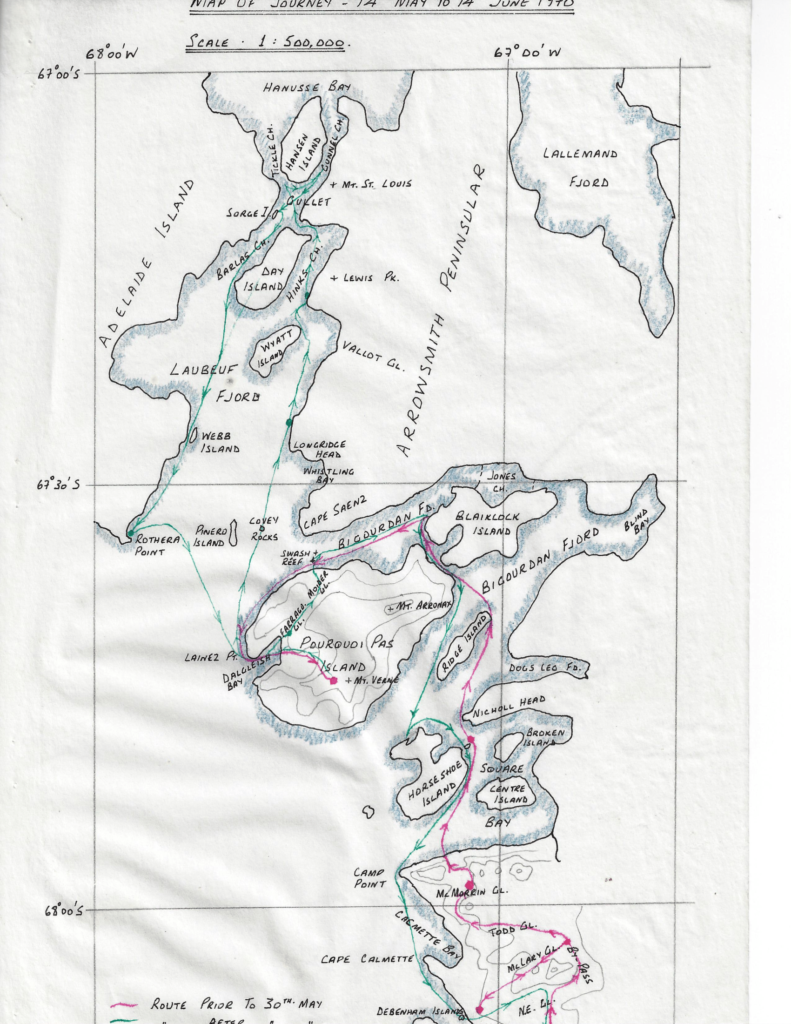

Attention turned to the Northern Fjords, Pourquoi Pas and the Arrowsmith Peninsula during the Winter of 1948. Ken Blaiklock, based at Stonington, surveyed the islands in northern Marguerite Bay and the east coast of Adelaide Island as far as The Gullet where there was open water, and then continued to survey the fjord area, running closed traverses around the major islands. Blaiklock also discovered the emperor penguin rookery on the Dion IslandsIn the winter of 1949.

Blaiklock again went North, and surveyed Bourgeois and Bigourdan fjords, visited the Faure Islands and carried out an astro-fix but the sight of open water brought a hasty conclusion to the work.

Horseshoe Island was established as a new base in March 1955 but poor sea ice in 1955 and 1956 curtailed activities. Derek Searle, working with Geologist Jim Exley, produced a 1:25,000 detailed map of the island for the geological work. They also recced a route up on to the plateau and another northwards. From a sun-fix at base and a baseline measured on the sea ice, a small triangulation scheme was beaconed and observed on the NW of the island and extended eastwards. A new field hut was erected on Blaiklock Island for further work.

Detaille Island Base was established in 1956, primarily for mapping, geology and meteorology as well as to contribute to the science programmes of the International Geophysical Year in 1957. Detaille operated for three years and in spite of the difficulties, much was achieved in terms of geological mapping and surveying of the surrounding areas. Before the sea ice formed a small triangulation scheme on the island was beaconed and observed and a detail map of the island performed at 1:2,400 scale. In 1956, sledge wheel and compass surveys where carried out along the mainland coast and eventually up onto the Avery Plateau at 1680m where they were able to link to work from Mason’s 1946 plateau survey and obtain a sun-fix. Hedley (Paul?) Wright conducted geological work alongside the survey work.

In 1957, sledge wheel and compass surveys of glaciers were made, into Darbel Bay and Lallemand Fjord and onto Avery Plateau. Better weather allowed some star fixes to be observed, while Denis Goldring conducted geological work. FIDASE photography had become available and the survey work changed to systematic triangulation to provide control points for mapping. Angus Erskine and Jim Madell measured a baseline near base and reconnoitered a triangulation scheme from 66.5s along the coast and down Lallemand Fjord which was observed in the spring. When the sea ice was unsafe further work was done on the local map for the geologist and a 16 star astrofix observed.

Based between Horseshoe and the Blaiklock Refuge in 1957, Peter Gibbs and John Rothera worked north into the Arrowsmith Peninsula between them and Detaille Island and west to Laubeuf Fjord with chains of triangulation and a 20 star astro-fix at Blaiklock.In 1958, John Rothera extended the triangulation into northern Adelaide Island and south to the work in Laubeuf Fjord and down the Lallemand Fjord to connect with the work in the Arrowsmith Peninsula, and Brian Foote extended the work northwards into Darbell Bay.

Further detailed survey work was done for geologist Denis Goldring, and in March 1959 Horseshoe Base was closed.

1965 – Restarting Work in Northern Marguerite Bay – From Mike Cousins BC Report

(Photo: Mike Warr)

The air unit comprising two Single Otter aircraft was incapacitated when VP-FAL, DHC-3 Otter, crash landed in poor visibility at Adelaide, 28 December, 1964.and was written off.

As a consequence, the KG VI Sound program was cancelled, and precipitated a last-minute upheaval, which in turn had a considerable effect on the Stonington personnel and programmes for the coming season.

Initially a wintering party of 8 was proposed, with considerable curtailment of field work. After various deliberations it was decided to winter a full complement of 13, with little, if any, cutting down of field work; in fact, the field work was necessarily increased, as the change in working areas meant that an Autumn programme could be undertaken, and so depot running had to be carried out. Coupled with this, the fact that a major effort was put into the construction of a much-needed extension of Stonington base hut, and that with subsequent modifications to the base hut resulted in a fairly busy year for most people.

The work program for field parties included the plan for Neil Marsden and Tony Rider to extend the local survey scheme control for the 1:50,000 map, and when ice conditions allowed acces to the Horseshoe/Pourquoi Pas area, work to be commenced on the interconnection of the previous schemes fromDetaille Island, Horseshoe and Adelaide Islands, involving both trig. and tellurometry.

A depot was dropped at Horseshoe base by the ‘Biscoe’, for the survey work which was intended using Horseshoe as the centre.

During the local work which extended from March to May, Neil Marsden’s partcipation was cut short at the nd of April by the loss of a tent and severe frostbite in his fingers. The Horseshoe survey program when Tony Rider, with GA’s John Tait and Jimmy Gardner left base to carry out reconnaissance and set up stations. The plan was for Neil Marsden with GA Edwin Thornton to join them at the end of September, after Neil’s incapacitation with frostbite was completed. Unfortunately the Programme met with an abrupt end at Detaille Island where the party became stranded when the sea ice went out, having called there to check on the hut and survey station.

Marsden and Thornton did make a trip to Horseshoe in November, so that Marsden could familiarise himself with the area in preparation for the following season.

None of the geologists had any specific instructions! and so it transpired after signals with London HQ, that MikeThomson and Keith Holmes would work on the East Coast, and Dave Matthews would be based at Horseshoe to continue the Northern Marguerite Bay geology program.

A Year of Geologising in Northern Marguerite Bay – Dave Matthews

The Landing at Horseshoe

(Photo: Dave Matthews)

I arrived at Stonington on “John Biscoe” in late February 1965 after the usual four months of pent up inactivity, to be greeted by two bits of news.

1) Jim Steen was to be my field assistant on an ambitious field programme sledging in southern Palmer Land.

2) One of the two old Otter aircraft had just had an accident and would not be available to support such a long range project, which was therefore cancelled.

Jim and I were instructed to return to UK on the “Biscoe“; a plan that did not appeal to either of us.

In the end, new plans were proposed and accepted by BAS HQ in London; some of the field teams to sledge down the east coast of the Peninsula, and myself to do geological survey in northern Marguerite Bay. Jim decided to go along with the latter and be my ‘gash hand’ for the bulk of the work, rather than go back to the east coast where he had been with Garrick Grikurov the previous season.

For the autumn, though, I was to start by basing myself on the old Horseshoe Island hut (Base ‘Y’) with Soopsey Vaughan as assistant and Noel Downham’s old team – the ‘Terrors’.

Soopsey and I and some basic supplies were to be dropped off at the old base on 1st April, extremely late for the “Shackleton” to be so far south, and it gave me only a few hours to discuss the work on the ground with Garrick who was on his way back to Russia. When the day came, we were onboard overnight as the ship moved from Stonington Island, across northern Marguerite Bay and into Bourgeois Fjord.

All night the sound of the rising wind rushing past the porthole kept me half awake, wondering if the weather would get too bad for a landing, but in the grey dawn light of a polar autumn things started to happen on deck. The launch on the “Shackleton”, its engine kept running all night so that the fuel pumps would not freeze, was jerked out of its cradle and was swung out over the ship’s rail. The winch held it at deck level, swaying and banging against the ships side while supplies were loaded into it with the waves hissing just below.

First the dogs; no easy matter to coax seven nervous huskies one at a time to jump across the gap into the swaying launch before being tied firmly so that no fighting could break out. Scared huskies are one thing, but a full-scale fight in that precarious situation could have been a big problem.

The winch man picking a good moment, there was a sudden sickening drop and a sheet of freezing spray flung up against the ice-caked side of the ship now towering above us, then the heavy throb of the diesel as it pushed us away from the shelter of the ship’s side, butting into the chop with icy spray flung stingingly into our faces by the wind.

Soon the landing place loomed ahead through the murk, the grey shuttered bulk of the old hut appearing fitfully. Hands and feet scrabbled for some grip on the snow-covered rocks of the shore, then the heavy frozen ropes were thrown and made fast. Manhandled once again, the dogs looked unhappy, but cheered up visibly as their feet touched solid ground again.

More loads of supplies followed as the launch shuttled backwards and forwards between ship and shore. Sledge, tent, personal belongings in bags and boxes and then the heavier stores; our lifeblood for the unknown months ahead. Heavy boxes of food, sacks of coal for the stoves, gallons of diesel fuel in heavy drums and finally fresh dog food in the form of seal carcasses shot a few days earlier but now frozen rigid and appallingly heavy. Many hands came to help as the rest of the ship’s passengers woke up, muffled against the unpleasant weather as they emerged from breakfast in the bright warm bowels of the ship.

Soon the last load was ashore, and people were shaking our hands and wishing us luck. Already the ship’s main engines had started and it was slowly hauling up to its anchor, while the launch finished its last run and was winched back on board with great sheets of ice flaking off the red sides of the ship; dramatic witness to the need for haste. The Antarctic winter waits for no one. No ship had been so far south this late in the season and if the ice should close in….., yet in five or six weeks time she could be steaming serenely through the tropics towards England and home. Such thoughts ran through my mind, but in no time at all, the ship was swinging round and threading its way through a group of icebergs. Fragments of sound from the engines and the ships’ bell reached us onshore against the rising gale, but there was no friendly hooting or waving goodbye. In a couple of minutes she was gone, lost from sight behind the giant bergs and the rocky headland, running for safety and a more northerly latitude.

No pennies for my companion’s thoughts; he had already endured one polar winter, but this would be my first. Just the two of us as we turned towards the darkened hulk of the hut, empty for the past few years. We were cold, wet and tired although it was not yet noon. It was 1st April and we were utterly alone – except for the dogs. The hut was dark and not a little ghostly, but once the stove was lit and the generator fired up, things began to feel slightly less forbidding.

Working for the Autumn and Summer from Horseshoe Base – Dave Matthews

Due to poor sea ice, Soopsey and I were still at Horseshoe for midwinter. A ‘rescue’ party of Keith Holmes and Jim Steen sledged over from Stonington in early July with more dogs to lighten the loads and help us for the 35-odd miles back to Stonington on thin ice.

The journey was eventful. In the winter darkness, Jim broke through a newly frozen and nearly invisible lead off Beacon Head and, following him, I could see three heads bobbing in the water; Jim’s and two seals.

We managed to pull Jim out and get the sledges across by charging the lead at a narrow point but it was my first experience of Jim’s toughness and obstinacy. Bearing in mind our precarious situation on thin sea ice off Beacon Head with no more land to the west of us, he refused to hang around putting up a shelter and changing clothes, insisting on battering on to Stonington (approx 25 miles) in clothes which were frozen rigid almost immediately. He survived with no more than extensive chafing and severe chill.

July 30th – Winter Survey Journey to Horseshoe and Detaille

(Compiled and summarized from John Tait’s Journey Report and Base Reports)

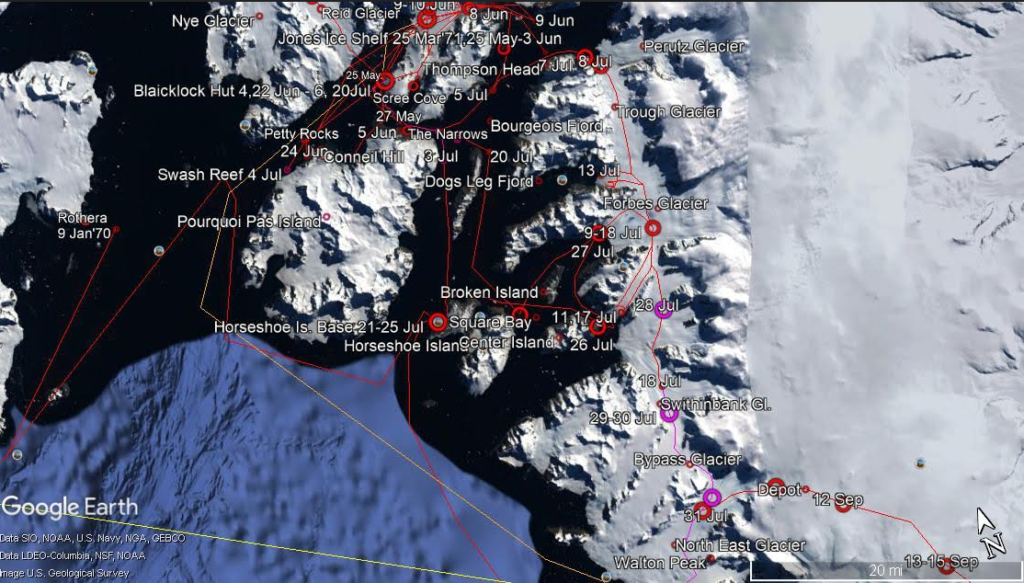

On July 30th, 1965, a three-man party departed Stonington with three teams, for the purposes of establishing a topographical survey connection between Bases W (Detaille Island), Y (Horseshoe) and E (Stonington); to lay depots for the Summer Survey; visit Detaille Island Base; and if possible to visit Adelaide, to pick up “certain items” necessary to the survey.

BAS Archives Ref: AD9/1/1996/14/27)

Tony Rider (Surveyor) was driving the Spartans, Jimmy Gardner (GA) the Vikings, and John Tait (GA) the Komats. The Journey had remarkably good surfaces and mostly excellent weather during the first half of August, enabling the party to lay all the necessary depots and reach Detaille Island (Base W) three days earlier than expected. The Sledgers established five (5) survey stations in preparation for the Summer Survey. Little did they expect what happened after that…

They left Stonington with a temp of 1 C, much of the surface being salty, wet sea ice which later improved and then worsened again as they approached Cape Calmette. They decided it was prudent not to travel to the next available camping point being Camp Point, 13 miles further. While camped at Cape Calmette after a lie-up day with wind and drift, they climbed a col on the Cape and noted that the open water was less than 20 miles away, seemingly stretching up into Bigourdan Fjord.

They lay up the next day in wind, and then on the 2nd August, a cloudless calm day gave them moderate travelling surfaces. They found the ice-edge to be much nearer to Horseshoe Island than they had anticipated, too close to be able to reach Horseshoe Base by the sea ice, and so they had to traverse overland, dropping most of their loads at the landfall onto the Island, arriving at the Base at 1700 hrs, with a temperature of -12 C.

The weather was good the next day, which they spent hauling the rest of the loads from their landfall point to the Base, and getting depots ready for departure to Blaiklock Refuge the next day, with temperatures at -18 C.

The next day, August 4th was fine and calm, with low lying fog, causing sea level visibility to be very limited. The dogs worked well, and they arrived at Blaiklock at 1600 hrs, having traveled 21.7 miles, with temps now – 20 C.

On the 5th, there was a lot of cloud, but calm, no wind. They laid a depot at the refuge hut, then travelled up Bigourdan Fjord to the Jones Ice Shelf. They had some difficulties getting up the ice cliff, but they eventually accomplished this and pitched camp half a mile from the cliff at 1500 hrs, having travelled 7 miles, with temp at -19 C.

On the 7th, the weather was generally clear except for some fog. They travelled to the opposite side of the fjord and set up a Survey station on a ridge. By the time they returned to camp, the fog had closed in, so the rest of the day was a lie-up, with temps at -18 C. The next day was a lie-up in wind and drift. On the 9th. August, they left camp later than usual at 1100, travelling to the Bucher Glacier where they set up a Survey station, and laid a depot. They returned to Horseshoe Island and Base Y, travelling almost 30 miles, with a temperature of – 23 C. The next day was beautiful and was spent at Base Y, preparing for the next trip. Temperatures now at -28.5 C.

August 11th brought continuing good weather, and the party travelled 25.7 miles to their previous campsite at NE Blaiklock, with excellent surfaces all day. They depoted most of their load. Temperature -25 C.

The “Glorious 12th” clouded in later, as they travelled up the Heim Glacier, encountering many crevasses. The Spartans dropped one dog into a crevasse, but he was recovered safely. A Survey station was established of the Heim, and they travelled until making camp at 1645 hrs, having travelled 14.6 miles in a temperature of – 27 C.

Over the next three days, they established two more survey stations, and Gardner and Rider recced the sea ice into Lallemand Fjord and reported it good. On the 16th they travelled up Lallemand to Detaille Island and Base W, including over some brash fields in the lower fjord. The base was found to be in good structural condition, but messy due to burst food cans in the loft which had dripped through the floor, and so spent the next couple of days cleaning up, and also killing a Leopard Seal which they fed to the dogs.

They awoke on the 19th to a Southerly gale, to see the sea-ice breaking up in all directions, temperatures at – 7 C. On the 20th the wind lessened, and they were able to see the damage to the ice – open water to the North, broken pack to the South. The situation looked bad to the party, but they had great hopes of the sea-ice reforming, temperature at – 2 C.

On the 21st, another gale, this time Northerly, at an estimated 60 knots, and so the day was spent establishing order in the hut, and bringing in food supplies. Temperature now – 1C. By the 22nd, most of the ice had disappeared, except for some fast ice in the bays of the island. Temperature now at +2 C. A recce of the ice on the 23rd indicated a possible strip of fast ice some 6 miles to the south. The party was hoping for colder weather, but at that point, and the next day, August 27th, the temperature was still only -4 C and there was no apparent way to reach the mainland.

On the 25th, with fine and calm weather, new ice was forming rapidly; later in the day, the barometer dropped and the wind was rising. “Is this the knell of doom for the new ice?” By the 26th, the new ice had broken up, and then started re-forming the next day. They tested the ice daily, and on the 30th, took the decision to leave the next day, but that day dawned with cloud, warm weather and heavy snow, preventing them leaving.

Overnight a Southeast gale blew up, playing havoc with the new ice. The next day, although the wind had died, the gale had opened up new leads everywhere, causing tremendous pressure in the new ice nearer shore, making for difficult sledging. They still hoped to make Johnson’s Point on the mainland on the first good day, but on the 3rd. September, the barometer dropped again, resulting first a Northern gale, then a Southern hurricane. The party were not expecting any new sea ice in those conditions.

The next day, September 4th, the wind was still blowing strongly from the South, but observations from the top of the Island showed that most of the ice had blown completely away, except for a strip attached to the mainland. The next day, there was “not a scrap of fast ice to be seen.” The Fids decided that they now seemed to be stranded permanently, or at least until a summer relief ship could reach them.

“The Further Exploits of the Stonington Castaways” – Keith Holmes, based on Tony Rider’s Report:

John Tait noted in his report that much conjecture arose, presumably at Stonington, as to whether they should have gone to Detaille. John stated that there was every indication of a continuation of the cold calm weather and that they saw no reason not to make the trip. That they did get “stuck”, rendering the completion of both the Spring and Summer Survey to be impossible, was due to the abnormally high temperatures accompanied by very high winds, which broke up the sea ice.

John Tait, Tony Rider and Jimmy Gardner became isolated on Detaille Island when the sea ice went out totally in warm temperatures and high winds. Following that realization, John Tait referred to themselves as the “The Stonington Castaways” in his Journey Report.

Tony reported on the state of the hut and wrote an account of the stranded party.

Their concern about being out of contact was alleviated when Jules Brett flew over them in the Single Otter 294 from Adelaide Island on October 4th. Becoming frustrated by inactivity, they dug out the fibreglass boat between October 12th and 18th, and thought about making an escape. They then had to spend several days excavating the limited amount of coal that was buried in a dump under the snow. Living off the land, they dined on roast shag, penguin eggs, and even skuas.

From October 24th to December 7th, Jules Brett made five more runs from Adelaide Island to drop 16 boxes of Nutrican for the dogs, 29 bags of coal, six batteries, and miscellaneous bits of clothing to them. On October 29th, John, now having enough coal, was able to cook a cake, but it needed eight hours in the “oven”.

By this time, they were thinking more seriously of escaping to the mainland in the hope that they could sledge back to Stonington along the plateau, although this had never been done before. On November 29th and 30th they floated the boat, repaired a hole in it, got the Arzani outboard motor working, and started to shifted sledging rations, camping gear, sledges and dogs to the tiny field hut at Orford Cliff (informally known then as ‘Johnston’s point’) on the mainland some nine miles away. This was already a dangerous venture because of winds, currents, and their reliance on a single motor, but, after a week, John, the helmsman, was eventually cut off by dense pack ice. Then the outboard packed up, and on December 7th, Tony was stuck with his team at Orford Cliff. Jules overflew him, but was unable to land because of crevasses.

Tony’s report noted, laconically, that on Detaille Island they got the rifle working on December 10th.

On January 7th, after a fortnight of strong wind, Jules made his last visit in 294 to drop a note telling the castaways that they should wait there until about January 20th, when RRS Shackleton would relieve them. The ship arrived on the 21st. The men and dogs were, fortunately, in good shape.

Returning to the Work Area in the northern Fjords – Dave Matthews

(Photo: Dave Matthews)

After three weeks on Stonington base to prepare for a long season, build sledges etc, Jim (Steen) and I set off for Horseshoe again, Jim with his team the “Ladies” and myself with the “Terrors”, and by now on slightly thicker sea ice. Jim’s plan (to avoid the risk of getting caught by unreliable sea ice on such a tricky journey, where only the inhospitable Camp Point afforded a possible refuge between Horseshoe and Stonington), was to recce an escape route from northern Marguerite Bay (Blind Bay) via the Plateau.

(Photo: Dave Matthews)

This meant laying depots up the Forel and Finsterwalder Glaciers from Blind Bay, which proved far from straightforward and was very time consuming, due partly to poor weather (including a record 16 day lie-up) and also avalanche dangers. The Forel Glacier was eventually “conquered” and the latter depot was eventually flown in, much later, to the upper Finsterwalder by the one remaining serviceable Otter.

With all the to-ing and fro-ing of building depots and so on, Jim’s great skiing skills were a big bonus and made me feel thoroughly inadequate, especially on the old wooden Fids skis. He could cheerfully ski down a steep slope with a food box on one shoulder and no sticks. That really pissed me off and I resolved to learn to do better.

(Photo: Dave Matthews)

The plans worked out well and we were able to progress to doing field work on and around Pourquoi Pas Island by later in September. This included an opportunity to make a First Ascent of Mount Verne, the prominent peak in front of the old Base Y, which Jim led with casual skill. Sadly a first ascent was wrongly credited, in the Damien Gildea book, to ship-based tourists some years later, when in fact it should have read “Jim Steen and Dave Matthews on Wednesday 3rd November 1965, via the North Ridge”.

Eventually it came time to retreat from the sea ice; we had already had one scare when we both broke through unexpectedly thin ice in the Narrows between Pourquoi Pas and Blaiklock Islands, presumably where under ice currents had eroded it to almost nothing. Also a survey party had become marooned on Detaille Island (Base W) when all the ice blew out of Lallemand Fjord, and there was some discussion of possibly picking them up, but to get them to nearby Prospect Point (Base J) from Detaille Island would have been a challenge and the idea was dropped.

We managed the ascent of the Forel and Finsterwalder Glaciers up the route we had already scouted. With adequate supplies, Jim decided that we could then afford to sledge north from the head of the Finsterwalder along the Plateau towards where Wally Herbert had reached his furthest south on the Plateau in 1956-57.

We reached Slessor Peak which we climbed and collected volcanic rock samples, enjoying stupendous views out to the west, but by that time, a Detaille Island rescue was no longer a plan. The “Shack” had already done it.

In spite of poor and intermittent radio contact, we gathered that the “Biscoe” had reached Stonington early for the annual relief, so decided that it was time for us to return south although I think Jim would have been quite happy to carry on up to the Catwalk and beyond. He insisted that we carry all our surplus supplies back south with us rather than waste them by dumping them, so it was heavy going but we were by now fit and used to adjusting loads between the two sledges to get maximum efficiency along the undulating plateau. Jim had to put down one of his old dogs who could no longer keep up and it was the only time I ever saw him in tears as he returned to the tent with a ‘smoking gun’.

We had both developed a tremendous bond with our dogs after six months of sledging.

At the Plateau Edge, we added our surplus supplies to the depot there before carrying on down Northeast Glacier under the threat of deteriorating weather, with Jim leading the way towards the fearsome Sodabread route so well known to Plateau sledge parties from Stonington.

Return to Stonington – without Claire – Dave Matthews

This part of the story really belongs to Claire, a ten year old bitch with several fine litters to her credit and a sledging career longer than that of most dogs in the harsh Antarctic conditions. She was born in 1957 at Hope Bay (Base D). By the time of this story, in 1965, Hope Bay had closed and Claire transferred, along with several teams, to Stonington Island a thousand miles or so further south (a journey, incidentally, that can never be repeated now that the Larsen Ice Shelf, along which the sledge route lay, has completely broken up and disappeared).

Two men and two teams (17 dogs in all) were returning to base at Stonington at the end of a six months journey. For Claire, her last journey was almost over and she would certainly be retired if not put down before the next winter came. Already too old, this last gruelling day returning to base was proving too much for her, coming after 180 days on dried rations and over 1000 miles of pulling. We were pushing hard to reach home before a threatened spell of bad weather moved in, making this a day which eventually found its way into the record books. After thirty tiring miles with heavy loads in seventeen hours along the undulating surface of the Plateau, a brief rest to unload the sledges and leave a depot of all unused ration and dogfood boxes, then the prospect of a final 26 miles running light and downhill all the way. The younger dogs were still setting a fine pace, and impending bad weather did not encourage any further delay so after unloading, old Claire was taken off the trace and lifted on to the back of the sledge astride the tents and gear, where she tried to maintain her dignity – though drooping with exhaustion. The rest of the team would run too fast for her to keep up, when they had only light loads to pull.

Descending from the Plateau edge down to Stonington Island was a formidable undertaking at any time. This was Sodabread, described earlier. Four thousand feet of very steep often dangerously angled glacier – icefall really, and seeming quite impassable – down which the sledging route took a sinuous line into a huge natural amphitheatre (The Amphitheatre); culminating in the infamous Sodabread Slope, a straight 500 foot plunge down a gradient of around 1 in 2.5 to the valley glacier below. The dogs behaved well. These were teams and drivers who had been through a lot together and the dogs seemed to sense that it was an especially tense moment. The precariousness of the route was not the only danger, for this ice fall was notorious also as a breeding ground for bad weather and fierce storms which plagued the area; a natural cauldron where winds could build up in minutes to a strength which could (and had) at times meant death to men and dogs.

No sooner was the difficult descent started than tell-tale streamers of snow began to appear on the tops of the surrounding peaks and the wind rapidly increased to a local gale. It was hard to believe our bad luck. Less than a mile below us on the valley floor it was still a fine calm evening while at the Plateau edge we had difficulty in seeing our lead dogs forty feet ahead, through the rapidly rising drift. The snow surface was difficult to see too – almost a white-out.

By the time we reached The Amphitheatre, conditions were really unpleasant but this was no place to camp and wait for an improvement. As we turned left onto the long, narrow oblique line of the traverse, standing on the uphill runner of the awkwardly side-slipping sledges while at the same time trying to keep the foot brake hard on, we shouted a continuous Rrrr, Rrrr – left, left – to keep the dogs high on the left side of the traverse. To let them head too steeply down to the right would lead to almost certain disaster in the broken chaos of the main icefall.

Then the inevitable happened on the icy surface being exposed by the wind. First, one sledge tilted awkwardly on a small hump, slipped violently sideways, and then tipped over onto its side. For the driver this was always a nasty thing to happen and, even with a lightly loaded sledge, a problem to sort out. For the luckless Claire, it was the last straw. Thrown violently from her perch astride the load, she staggered to her feet, dazed and shaky and then set off up the slope, deaf to all shouts and entreaties. In no time she was just a white shadow in the drifting wilderness of snow; then she was gone. In moments, neither she nor her tracks were visible. ‘She has gone to die’, we thought. Searching for her was out of the question. There were other lives at stake now and with heavy hearts we turned our attention urgently to sorting out our own tricky situation, before it became seriously dangerous. With two teams and two sledges still to be extricated from such unpleasant circumstances, the complications and risks of starting a search for a single dog did not even bear thinking about.

Throughout the rest of that long descent there was no time to spare for recriminations. At the end of the traverse there were rope brakes to pull out and fit for the final hair-raisingly steep plunge to the valley floor. The number of turns of the rope around the sledge runners depended absolutely on the depth and consistency of the snow; getting it wrong could mean all sorts of trouble. Then, the moment of commitment. Like starting an abseil down a cliff face, there was no turning back. The whole team hung forward in their harnesses, their weight inevitably adding to the strain on the footbrake. The sledge hurtled downwards, almost over-running the dogs, and kicking up blinding clouds of snow from the ropes and the foot spikes. At last, just as men and dogs were at the limit of their endurance, the run-out onto more level valley glacier and, on my sledge at least, the ropes frayed to within one strand of parting by the icy crust hidden beneath the surface powder snow.

Now, after hours of intense effort and strain and with easier gradients and not too many crevasses in front of us for the final 20 miles, most of the tension drained away and there was time to relax a little and take in the grandeur of our surroundings. The wind howled impotently across the cliffs above and behind us, and while the sledges and skis hissed over a hard surface and the teams ran at an exhilarating speed through the long sunset of the polar summer night, we wondered about Claire. It was a dramatic way to meet her end. Perhaps she fell into a crevasse or perhaps she curled up and went to sleep in the storm. In either case, the end of a life but not without a certain sense of ‘rightness’.

After our safe return to base, the bad weather developed into two whole days of storm over the area, obliterating all our tracks and making us heartily glad not to be pinned down in our tents on the Plateau edge. Normally we might have kept an eye open for a stray dog to return; a young dog perhaps, returning over the sea ice where there was food in the form of seals and penguins. But an old dog lost in an icefall 20 miles up a difficult crevassed glacier with no food and no tracks to follow…… there was no point. Besides, there were all the delights for us of a return to relative luxury. A bath – if you filled the melt tank – and the rare experience of a whole year’s mail to read. The teams had to be settled onto their summer spans and fed fresh meat and blubber to bring them back to condition. So the days went by, soon running into weeks

It was five o clock one morning that several of us heard more noise than usual from the dog spans, but not enough to get us out of bed to investigate. The spans were a quarter of a mile away and there were over 100 dogs there. Probably an inquisitive penguin or something causing a bit of excitement. It didn’t sound loud enough for a fight or a loose team. Those of us who heard it, turned over and went to sleep again.

As luck would have it, the first person out of bed at the more normal breakfast hour was Jim. No-one knew Claire better and yet he hardly recognised her where she lay by the hut door in the morning sun. She could hardly stand up to be greeted or to accept food and she looked little better than a furry skeleton. She submitted to being fed a little and fussed over before turning away from us and giving in to a long, long sleep in the warm sunshine. The two of us, still blinking with surprise and emotion, crept back indoors to consult a calendar. It was eighteen days since that epic descent when we had lost her.

The story might have ended there. Claire took food only slowly and appeared to regain very little of her condition in the weeks following her return. It was decided that she had earned a chance to survive the oncoming winter at a more northerly base so she was retired to what was at that time the Antarctic’s closest approach to a rest home for old dogs, where she would be treated well and where she might be used occasionally for short recreational journeys.

One year later I saw her there and once again could hardly believe my eyes, such a sleek and contented-looking animal came to greet me. Only a trace of stiffness in the legs and a tinge of grey around the muzzle gave her away. By then she was eleven years old and few huskies lived to such an age in those days in that part of the world.

Our six month trip together was over, but it had included many shared moments of deep emotion and of course our share of tensions and disagreements. Jim was a strict disciplinarian in many respects, especially with his dogs, but usually it paid off.

I heard from Jim once more when he was back in Norway before returning to his adopted Canada. It was written on the headed notepaper of his family shipping business in Oslo and was already full of nostalgia for his time south. I realised then how little we knew of each other’s lives outside BAS. I knew that he had been a good skier (one major accident) and I knew that like me he was unmarried. My abiding memories of him are of an extremely able and competent mountaineer and skier, and of a trustworthy, reliable and rewarding companion and friend.

Dave Matthews – Geologist – Stonington – 1965 & 1966

1966 – Continuing Work in Northern Marguerite Bay – from Terry Tallis’s BC Report

The tragic loss of John Noel and Tom Allen in May, together with two dog teams, inevitably necessitated some reorganisation of base duties, but did not curtail the field programmes as might be expected, and with the excellent support of the Single Otter VP-FAK, piloted by Bob Burgess and at the latter end of the season, Bob Vere, the program was carried out to the best of everyone’s ability.

The geology field programs were such that Keith Holmes continued the work he and Mike Thomson had commenced in 1965 on the East Coast of Palmer Land, and Dave Matthews, with GA John Noble, returned to Horseshoe to continue the work in Northern Marguerite Bay. The ‘Biscoe’ landed them at Horseshoe at on March 13th. Matthews finalized his work from the previous season on the Island, and returned to Stonington on June 12th when the sea-ice had formed.

Matthews and GA Ken Doyle again left base on September 14th, to complete his work in the fjords from the sea-ice, and finally returned to Stonington on November 25th, having virtually completed his work except for finalising Calmette Bay, which he did in two days from Base withTerry Tallis and a day with Ken Doyle.

1967 – Continuing Work in Northern Marguerite Bay – From Alistair McArthur’s BC Report

The Single Otter aircraft VP-FAK was grounded in March 1967 due to metal fatigue, leaving only the Pilatus Porter, and then in December 1967, the replacement Single Otter, because of the volcanic eruption at Deception Island, was offloaded at South Georgia and never made it to Marguerite Bay. Consequently air support for the southern programs was limited, and much of the aircraft time was used in evacuating personnel from Fossil Bluf in addition to re-supply.

Concentration in the field programs during 1967 was in the King George VI Sound programs, with eight Surveyors, Geologists and GA’s and eight dog teams sledging south starting in August and September. Before that, with the sea-ice in good condition, and permanent between Stonington and Horseshoe from May through to December, several journeys were made to Horseshoe from Stonington, and one to Adelaide, whereas to the south of Red Rock Ridge, the sea-ice was unuseable until September.

A journey was made to Horseshoe from May 26th to June 16, making use of the good sea-ice, for Geomorphology by Dick Boulding (Surveyor), together with Dave Horley (GA), George McLeod (GA), Owen Collings (Carpenter) and Bob England (GA) and four dog teams.

George McLeod and John Noble (GAs) with two dog teams sledged to Adelaide in July, but were prevented from returning due to unstable sea-ice.

Multiple trips for reconnaissance and vacations were made to Horseshoe during July, involving Horley (GA) Smith (Geologist). McArthur (GA), Postlethwaite, (Surveyor) DAwson (DEM), Williams M.O.), Madders (Radio Op) and four dog teams.

1968 – Multiple Journeys into the Northern Fjords – including from Alistair McArthur’s BC Report

On 26th February 1968, the BAS single-engine Pilatus Porter piloted by RAF pilot John Ayers landed on the Grahamland Plateau at the junction of the Millet and Meikeljohn glaciers in order to pick up a geological field party consisting of Rod Ledingham and Graham Smith with their team of 8 dogs.

During the subsequent take-off, an under-carriage weld failed, causing a ski to turn outwards, and in bringing the slewing aircraft under control, the tail ski was torn off – damage that could not be repaired in the field.

However, John Ayers assessed that with skis removed, the crusted surface might allow a take-off on wheels, and this nearly succeeded until a wheel broke through the crust, tipping the plane onto its nose and bending all three propellor blades.

The location where the Turbo-Porter crashed was named “Porter Nunatak” by Flt Lt Ayers and is still referred to by that title. The crashed aircraft from thereon became to permanent marker for Porter Depot.

After the Pilatus Porter became “unserviceable” (crashed!), once again the year’s field program was somewhat altered.

As an alternative to the planned work south of Ablation Point, geologist Lew Willey surveyed the local islands around Stonington and Neny Island in detail.

The Survey party comprised Surveyors Mike Fielding, Derek Postlethwaite and Phil Wainwright, and GA’s Jack Donaldson, Ken Doyle and Ian Sykes, with four dog teams. They continued their planned work (under appalling weather conditions) in the Fjords on the Graham Land scheme, returning to Stonington on the 8th July after 4 months in the field.

The Geophysics party comprised Geophysicist Ian Flavel Smith, Geologist Lew Willey, and GA’s Alistair McArthur and Shaun Norman, with four dog teams. After Midwinter, the party travelled to Horseshoe Base for a month over June/July and continued the program successfully. A further six weeks was spent from October 26th, travelling from Stonington to Adelaide and then back to work in the Debenham Islands.

The work of both the Survey and Geophysics parties was curtailed when an estimated 140 knot wind took out out much of the ice in Northern Marguerite Bay.

1969 – Arrowsmith Geology & Geophysics – From Shaun Norman’s BC Report

At the end of the relief season 1968/69, the ‘Biscoe’ landed a four man field party and reopened the old disused base on Horseshoe Island. Geophysicists Ian Flavel Smith and Mike Burns, Pete Rowe (Geologist) and Ian Sykes (GA) with three dogs teams were taken by the ‘Biscoe’ to spend the winter doing geology and geophysics, before setting out south for the spring journeys. Close detailed magnetometer and gravimeter surveys were carried out from the Base hut and also from camps. Sea ice magnetics were commenced about May 25th, and continued almost to Midwinter.

After Midwinter, the party travelled to Adelaide Island, where they met up with two Adelaide GA’s, Ian Curphey and Rod Pashley, travelled back to Horseshoe and then continued work in Square Bay before returning to Stonington in early August.

Pete Rowe was able to get in some geology during the geophysics,

Added with the Kind Permission of Ian ‘Spike’ Sykes from his book “In the Shadow of Ben Nevis” (available on Google Books).

The ‘Biscoe’ left the four us waving goodbye from the beach among a pile of boxes. Ali MacArthur our Base Commander, Chris Madders the radio operator and Derick Postlethwaite were all leaving for home having completed their two year contract, and we had become the old hands. It was a strange, lonely moment watching the ship moving slowly out of sight among the icebergs. In a few weeks they would be back among their families, the humdrum of normal life, trees and grass and fresh fruit and perhaps the scent of a girl. I suffered one of those pangs of desperate loneliness that all of us must have felt at times. It was a rare feeling, usually we were too occupied to worry about home so on these occasions I found it best to sit with my dogs.

The old base was in a bad way but we soon had the generator running and a roaring fire in the main hut and settled in for a cosy winter. The scientists were doing a detailed gravity and magnetic survey of the island and I followed along with the theodolite, mapping the position of their work. It was a relaxing time with just the four of us, a time to dream and make plans.

We listened to the news on the world service, the Cold War was at its height and young American soldiers were coming home in body bags from Vietnam, closer to home Bernadette Devlin was tearing up pavements in Northern Ireland. This, the start of ‘the troubles’, seemed unbelievable to us, such things couldn’t happen on the streets of Britain. It all seemed a long way off; our little world was one of ice, storms and stars, of dogs and cold, warm fires and good books. Work was relatively easy doing a gravity and magnetic survey of Horseshoe Island and Square Bay. Midwinter was a cheerful time with just four of us on the island.

With the return of the sun we set out to meet Ian Curphey and Rod Pashley who were sledging from Adelaide Base to meet us for the summer sledging in George VI Sound. Curph and I had become friends on my journey south and he had returned to Britain as an engineer on the Shackleton and then managed to get a job as a dog driver with the Survey and here he was back again, as large as life.

19th July

Leaving Horseshoe we sledged up Bourgeois Fjord passed along Ridge Island and through The Narrows between Pourquoi Pas and Blaiklock Island and then nervously across the long twelve mile open sea crossing of Bigourdan fjord and passed Pinero Island on very wobbly thin sea-ice. We reached Adelaide Island at Rothera Point which was a small gravel spit of land which we knew had been the original planned site for Adelaide Base. Here we met up with Shaun Norman and Tony Bushell, more Stonington sledgers heading to Adelaide base and the whole lot of us set off up the island in appalling deep wallowing snow and made camp just over the McCallum Pass. We discovered we were less than a mile from Rod and Curph. A disappointing radio message that evening from Adelaide Base said that the doctor had let off a common cold virus and didn’t want us to visit during his experiment, of all places not to be welcome!

The following day we met up with Rod and Curph. They had driven their dogs across Adelaide Island in deep wallowing snow and were glad to join up with us. We all headed back over the pass and down to Rothera Point where we camped on the sea ice in a small bay.

**(This is now the site of Britain’s largest Antarctic base with a jetty capable of mooring research ships and a tarmac airstrip running out into the sea, laboratories, aircraft hangers and a small town of buildings. Visiting it in 2002, Curph and I found it unrecognisable to the lonely place where our two parties met thirty years earlier. We felt like two old buffers from the dark ages.)

We stayed another day at Rothera, my party heading up the fjord geologising and Rod and Curph sorting out a depot of man and dog food on beach. Tony and Shaun headed off back towards Stonington. We then followed our old tracks back across the fjord and camped on the sea-ice in a small bay on the tip of the Arrowsmith Peninsula at Cape Saenz. The following day we sledged up the coast of Bigourdan Fjord in beautiful but freezing cold weather through glorious mountain scenery and reached Blaiklock Hut where I had spent an enforced Mid-winter the previous year.

An incredible event began to unfold as we packed up our tents the following day on our journey back to Horseshoe Island. The surveyor Mike Fielding with Mick Pawley and Brian Sheldon were camping on the far side of the Jones Ice-Shelf shelf and called us up on the radio.

“Can you come over to our camp tonight,” Mike asked? “There’s something I want you to listen to.”

It was a long cold day (-30) and we had difficulty getting on to the Jones Ice-shelf with some big crevasses to cross. It was getting dark but once on the shelf it was relatively safe on its flat surface and it was the most perfect night, not a cloud in the sky and a full-moon lighting the ice-shelf and surrounding mountains.

We set off on the last six miles of our journey casting long moon-shadows on the perfect crisp and flat snow of the shelf with the Milky Way, a gleaming mass of stars leading our way overhead. With a mile or so to go we could see Mike’s tent lights and the two teams of dogs with him began to howl. Our four teams burst into a gallop and we had an exhilarating race into their camp where the men rushed out to help us picket the dogs. Mick Pawley began calling urgently from the tent.

“Quick, come in, listens to this, and leave the dogs!!”

We all scrambled into the tent and sat around the radio where we were just in time to join millions of people the world over, crammed around television and radio sets as Neil Armstrong’s crackling voice came over the air.

“Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

It’s hard to describe the thrill of the moment as Neil’s voice came scratchily through the static. Surely in the entire world there wasn’t a place more remote and beautiful to listen to such an event. It was a terrific moment; there were nine of us crammed in the tent and parked outside were well over fifty dogs. The full moon was gleaming overhead and the dogs howled into the night with us joining in. Incredibly there was a better map of the moon’s surface than the part of the world where we lived.

Sometime later Neil stepped gingerly out onto the moon’s surface.

“That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.”

There were nine of us crammed in the tent Rod Pashley, Ian Curphey, Ian Flavell Smith, Mike Burns, Pete Rowe, Mike Fielding, Mick Pawley, Brian Sheldon and myself. Like everyone else we waited for the next thirteen hours with our ears pinned to the radio praying for the safe take off of Eagle with Neil and Buzz Aldrin, to join Michael Collins orbiting in the main capsule to take them on the long journey home.

Ian Curphey’s diary is well worth reading on that day and gives a wonderful picture of what polar travel was like.

Sunday July 20th 1969

“Very cold today minus 30 C. Left Blaiklock at 1045 and travelled up Bigourdan Fjord to the western end of the Jones Ice shelf, beautiful scenery on the east side of Blaiklock, towering pinnacles of rock enhanced by the light that painted the summits pink. A low bank of cloud that drifted out of the great valley that the Heim Glacier has carved, making everything seem very still and eerie.

Access to the Jones is on the north end where a large mass of ice stands proud of the shelf. To the left was a ramp which was quite easy to get up. The surface (snow) was very good but the cold was unpleasant, especially for Rod and I who were going too well and had to ride a lot (on the sledge to slow it down). We encountered many crevasse and Rod turned over (his sledge) on one bridge. I went back to help him and did a bloody stupid thing by walking back without skis. Sykes, rightly so, went spare. I deserved a bollocking for behaving so bloody daft in such a desperate place. About 100yds further on I went through one (crevasse) and only my sledge loop stopped me. Not a very nice feeling. At the eastern end of the Jones we camped where we met the survey party of Sheldon, Fielding and Pauley. Went into their tent for a brew (9 of us all told) and listened to the Yanks land on the moon! What next? Fids on the moon, lunar sledging? A good day but very cold for travelling.“

Curph’s quite a bit bigger than me so it can’t have been much of a bollocking. This was his first sledge journey and he and Rod Pashley had taken over dog teams at Adelaide Base with nobody to teach them the ropes. They had done a marvellous job of self-training and had only just joined us in the fjords. He seems less impressed with the moon landing than I was.

Sometime later I discovered that we were not the only polar travellers listening to Neil and Buzz landing on the moon. Almost directly opposite, on the other side of the planet, Wally Herbert with three companions was floe hopping, over breaking up pack ice, the final miles to Spitsbergen after a 3600 mile traverse of the North Pole. They had started from Point Barrow in Alaska on 21st February 1968 and reached the pole on April 6th 1969. They reached Spitsbergen 15 months later on what must be one of the greatest of all sledge journeys. He became the first man undisputedly to walk to the North Pole. Unfortunately their triumphant return coincided with the Lunar Landing and hardly got a mention and it was to be many years before his great feat was recognised. He was knighted thirty years later in the year 2000.

Geology & Geophysics – The Arrowsmith Peninsula – 1970

Following arrival of the R.R.S. John Biscoe at Stonington in early 1970, a party of five comprising two geologists, Gwynn Davies and Ali Linn, two geophysicists, Mike Burns and Pete Butler and one general assistant, Mick Pawley, were dropped off by the ship at Dalgliesh Bay, Pourquoi Pas Island on 21 February.

Sledge Bravo comprised Mike Burns with the Terrors and Gwynn Davies with the Ladies, and Sledge Charlie comprised Mick Pawley with the Giants, Pete Butler with the Spartans and Ali Linn. Supplies and equipment were included to keep the party until the sea ice formed to allow the group to sledge back to Stonington. On 9 March Alpha-Mike the Turbo Beaver landed on the Moider Glacier to bring in additional supplies and equipment and Mick, Mike and Gwynn were taken on an air recce of the island which was very useful to determine sledging routes and access to outcrops.

The island was found to be fairly easily travelled for the geophysical surveys and rock outcrops were very accessible from the glaciers. A lack of snow cover and good light conditions helped greatly in recognising rock types and relationships on the steeper rock faces; consequently, it was possible to map the geology of most of the island in the three months spent there. Coastal work from the sea ice was left until last but was hampered by lack of time and lessening daylight.

The sea ice formed in late April, and following a recce of the sea ice in Dalgliesh Bay by Mick and Mike where the ice thickness was 7 inches, Sledges Bravo and Charlie sledged to Blaiklock Island. The sea ice was accessed from the Swash Reef ramp and while the ice thickness at the ramp was 5 inches it increased northwards.

The geology and geophysical surveys of the PQP area continued through May until 2 June after which preparations were made to return to Stonington. During May the group were joined by additional sledges from Stonington and some changes of personnel occurred.

The system of being put ashore by the ship was successful in providing an extra two months work in what turned out to be good weather with longer daylight hours. Total days on PQP were 103 with 16 lie up days. The dog teams travelled an average of 500 miles.

The success of the PQP venture led to the reconnaissance of the Arrowsmith in July 70 and the planning of the 71 Autumn Arrowsmith programme with the Bransfield.

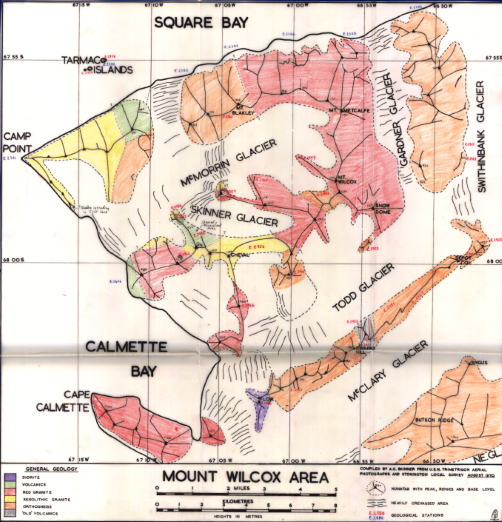

The Geology of the Mount Wilcox area, between Calmette and Square Bay Coasts, McClary and Swithinbank Glaciers – Ali Skinner

This year, with the formation of two new dog teams at Stonington, logistics permitted a local geological survey to be carried out ae well as the usual ground survey for aerial photograph control.

As no instructions were to hand for local work in Northern Marguerite Bay this autumn, and the previous year’s Blackwall Mountains work still could not be done as there was no sea-ice, it was decided to attempt a survey of the Mount Wilcox area between Calmette Bay, Square Bay, Mclary and Swithinbank Glaciers. This work would tie In with the work done the year on the McClary, Swithinbank and Northeast Glaciers and also be of value as the area was still untravelled, the geology of the area being done from coastal outcrops only.

Henry Blakley (GA) with the Vikings, and Ali Skinner Geolgist) with the Gaels set out to follow a route from the McClary Glacier into the Todd Glacier, which was known from a previous journey, and it was hoped that with time and good weather the area could be ‘opened up’ to sledges. This in fact proved to be much easier than anticipated and a very successful autumn was spent in geologising the area. Cape Calmette itself could not be visited from the glaciers and the Gardner Glacier was too badly crevassed to travel.

As the map of the area was almost blank and the rest of the contoured area largely meaningless, plane tabling was carried out in each of the glaciers by Henry Blakley.

This was later used to provide additional control when a map was produced of the area using the United States Navy Trimetrigon aerial photographs and the local Stonington Survey scheme for ground control. This map (on a scale of 1:50,000) was considered accurate enough for plotting purposes and travelling – more ground control and more photographs at the Square Bay end (where many points are fixed only by two intersections) and a knowledge of the area would have been useful).

Following the completion of the Wilcox area, Neil McAllister and the Debs joined Alistair and traveled to the west end of Butson Ridge was visited in order to complete work outstanding from last year and a few days were also spent in Square Bay so that the programme commenced there in August of last year could also be completed.

Alistair Skinner, Geologist (Stonington, 1969 & 1970)

May 1970 – First Winter Reconnaissance Journey – Steve Wormald

In May of 1970, Tony Bushell, Steve Wormald and John Newman (DM heading to fix the Horseshoe generators), headed out on the First Winter Reconnaisance Journey from Stonington.

The sea-ice had gone out from the Stonington local area so with vague ideas of reaching the ‘good ice’ in the fjords, we decided to try to reach Square Bay, overland from Stonington, using the McMorrin Glacier outlet into Square Bay. Having succeeded in doing this, the whole world was open to us. We joined the party of geologists and geophysicists that had been left by the ship on Pourquoi Pas Island and helped them complete the work on the interior of the island. John Newman (DEM Stonington) then joined the Geology Party so he could go to Horseshoe Base and fix the generators. Mike Burns (Geophysicist) joined us and we headed north up Laubeuf Fjord . Keeping to the East on the on the way we got through The Gullet, not without incident, but were eventually stopped three miles up Gunnel Channel by open leads.

We then south keeping to the Adelaide coast and met up with Adelaide Sledge Whisky (Hesbrook, Bird and Scoffam) with the Huns and The Rabble. This party came with us to PQP and helped move the remains of the winter depot, some 2500 lbs, over to Blaiklock.

All through the trip we had the most marvellous weather and sledging surfaces were near perfect all the time.

May 14th – Away from Base by 10:00 with clear skies and three weeks of food, rapidly up the Northeast Glacier and the By-Pass with the Admirals leading. Arrived at the col between McLary and Todd Glaciers to meet up with Sledge Alpha (Woodhouse and Blakely), who were waiting for the new tent poles and laminated Nansen bridges we had brought up (that’s a whole other story). After sledge repairs, and ferrying nutty up to the col, both Sledges travelled rapidly back down the McLary to camp at the extreme western end of Butson Ridge, in beautiful weather and -15C.

Four days of lie-up followed, in snow and wind, but in occasional clearances, we watched the sea-ice go out from Stonington.

May 20th – All three teams ferried 1,000lbs up to the col, with the Komats leading. Heading down the other side from the col, the second team, the Admirals, decided on a short cut instead of following the track along the edge of the bergschrund, and Steve and the Admirals all crashed across the bergschrund and down the other side of the col. Luckily, everybody still in one piece.

We spent the next day finding a route down the northern outlet of the McMorrin Glacier, and after crossing crevasses throughout the day, the route narrowed down to two or three yards in the gully next to the rock, and then dropped suddenly for 50 feet to a flat area leading off into Square Bay. We camped just above the gully, and then the next day, after lowering all the gear, 1,000 lbs of stores, and all the dogs, we were able to head off across Square Bay on excellent sea-ice to Reluctant Island, where we and the dogs dined on seal that night.

A week was spent reorganizing the sledges and people, including John Newman joining Jim and Gwynn to geologize and also take John to Horseshoe to work on the generators, and then working with the geologists in the rocky corries around the Wells Glacier. On June 1st, after 13 successive travelling days, a lie-up day, with temperature soaring to -3C while snowing and blowing.

The next day, June 2nd, brought clear skies again, and 15C, and with the Admirals leading with a light load in the dark at 9:15 am, surfaces were good until the area where the Hinks Channel met The Gullet, where the sea-ice went from two feet thick, down to 6″ of soft ice. Three times the Admirals sledge went through the ice, each time the dogs pulling sledge and Steve out with their momentum.

Later in the day, having reversed the sledge order, with the Admirals at the rear and fully loaded, again the sledge went through the ice, and one of Steve’s skis disappeared into the icy depths, causing a one-ski technique for the next 100 miles, much to the amusement of the others.

We then headed across towards Tickle Channel but encountered open water again, and so we crossed back over to The Gullet, a very narrow and impressive channel with surprisingly, good solid ice again until, three miles up the Channel at the narrowest point, we encountered open leads, and a Leopard seal. Further progress was impossible and we camped on Serge Island after a 20-mile day.

On June 3rd, heading out in the black dark, there was some fun first finding and then descending the ramp back onto the sea-ice, then travelling and doing gravity readings until meeting up with Sledge Whisky (Hesbrook, Bird and Scoffam from Adelaide) just short of Rothera Point, and then sledging through heavy brash to camp on Rothera Point. The next day, leaving through heavy brash again, with the dogs and sledges getting a hammering through the first four miles of brash with very little snow cover, and then an easy run to Dalgleish Bay on PQP, another 20-mile day.

Two days of lie-up again. Windy in Dalgleish Bay, and so we were not surprised to hear of 100 knot winds at Stonington and Adelaide, and much of the sea-ice disappearing, although still holding fast in the fjords.

On June 7th, we cleared all the geological rock boxes from the depot, and then the Admirals led up the Ferrago Glacier to the depot at the top, which after we cleared the depot gave us a total load of 3,700 lbs. Running quickly back down to the sea ice, a 6′ cliff with a ‘Fids ramp” smashed up the sledges badly – the Terrors broke a runner, and the other sledges broke bridges. After some reorganisation, the Admirals, Huns and Rabble went ahead to break trail, while the Komats and Terrors limped along with a runner completely snapped in half, all sledges arriving at Blaiklock in the dark.

A day was needed at Blaiklock to repair sledges – Mike fixed a ski under his broken runner, and Steve found out he also had a broken runner, and so travelled backwards to Horseshoe before both sledges could be fitted with new runners there. We also redesigned Blaiklock, pulling down some interior walls, and building four decent bunks around three of the walls.

After two days at Horseshoe, fixing Squadcal radios and sledges, we headed back to the Debenham Islands (‘Debs’) and after a 32-mile day, with the last three hours in bright moonlight, we arrived to find Sledge Alpha (Jim Woodhouse, Henry Blakely and John Newman) stoking up a very welcome fire. As the sea ice was bad or gone between the Debs and Stonington, we were forced to head up the ramp and head back via Walton Peak and the Northeast Glacier to reach Stonington, a 15-mile detour to cover the last five miles.

The Journey took 32 days, with 6 lie-up days, and covered 368 miles.

July 1970 – Second Winter Reconnaissance Journey – Steve Wormald

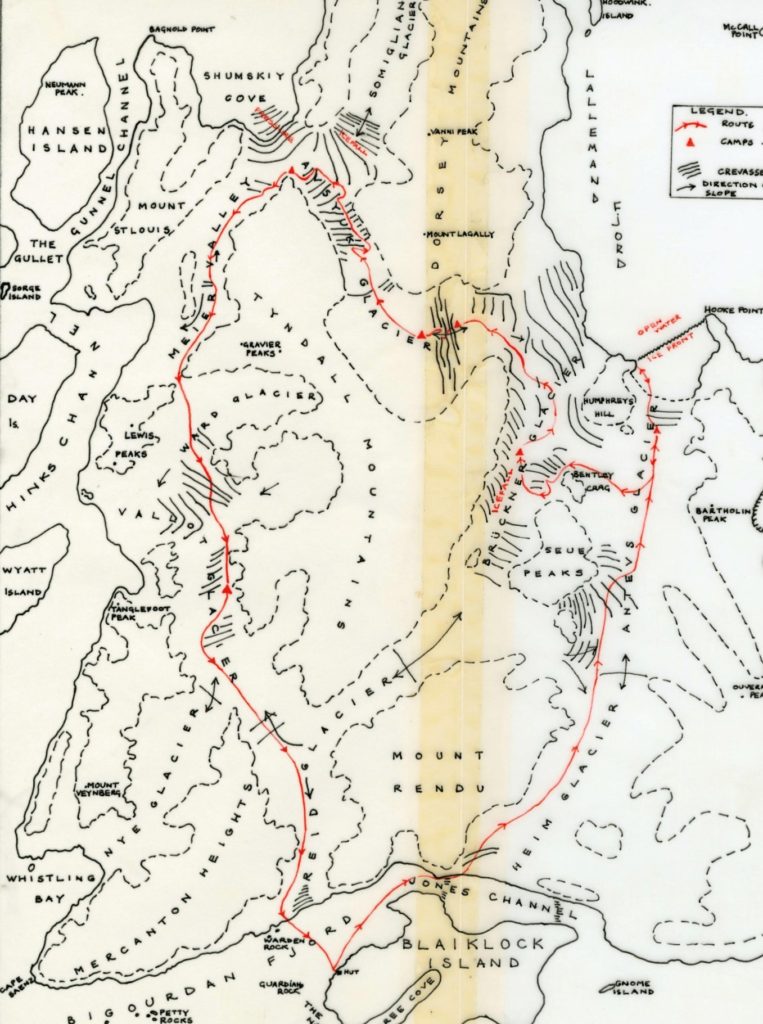

The purpose of the journey was to head to Lallemand Fjord and then recce the Arrowsmith Peninsula glaciers and recce routes from the fjords for the future Arrowsmith geology and geophysics programs.

Gwynn Davies (Geologist with the Ladies), Steve Wormald (GA, with the Admirals), travelled from Stonington to Horseshoe in company with Jim Woodhouse (GA) and Ali Linn – (Geologist). We then moved on to Blaiklock Refuge hut and met up with (Mike Bell (Geologist), Richy Hesbrook (GA) and Rod Pashley (GA) travelling from Adelaide

Rod Pashley with the Picts joined us – (an ideal party – 3 teams, one tent) and we left Blaiklock with the primary aim of finding a sledgeable route up the Heim Glacier from the Jones Ice Shelf. This proved much easier than anticipated, and we traveled up the Heim and down the Antevs Glacier in to Lallemand Fjord in a single day.

The next aim, to sledge up the Bruckner Glacier from the sea-ice was prevented by open water. Retracing our steps up the Antevs Glacier, an alternate route was found into the Bruckner, and then, via the Avsyuk ‘East’ and ‘West’ Glaciers into Shumskiy Cove.

From there, our route lay along the Meier Valley to find a way into the Ward Glacier, returning to Blaiklock via the Vallot and Reid Glaciers.

As a result of this journey, Gwynn Davies was able to form some ideas of where geology can be carried out with little or much difficulty, in preparation for the proposed Arrowsmith program in 1971.

The journey was uneventful other than the bad weather, and the usual route-finding and crevasses on the multiple glaciers. The 233-mile journey took 19 days, with 5 lie-up days.

The glaciers were found to vary greatly for ease of travelling and some interesting routes were found and sledged. Several possibilities were also seen for ‘empty sledge’ work in the area, notably a possible short cut by a low col from the Avsyuk to the Ward glacier. The easy col into the Ward from the Meier Valley also cuts out the need for sea-ice to completely circumnavigate the Peninsula. The ‘Reid Interconnecting’ appears to be easily sledgeable when viewed from both ends, although it will need approaching from the southern (Heim) side, as the access into the Antevs appears to be an icefall.

1971 – Arrowsmith Geology & Geophysics Program – Gwynn Davies

(Photo: Steve Wormald)

The Arrowsmith Geology & Geophysics Program formally started in 1971, after the reconnaissance journeys in 1970; in 1971 and 1972 Autumn Geological and Geophysical programmes were carried out on Pourquoi Pas Island and on the Arrowsmith Peninsula respectively.

Arrowsmith Peninsula Geology & Geophysics – 1971 – Brian Hill

(Photo: Steve Wormald)

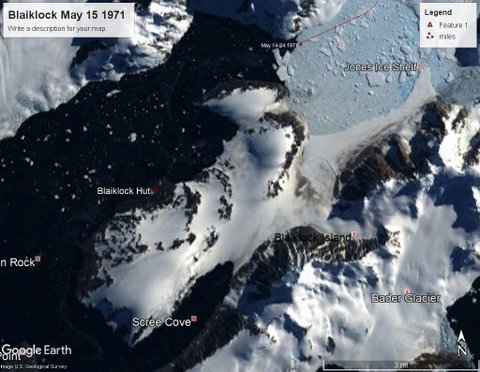

Six of us were landed on the Jones Ice Shelf from the Bransfield in March 1971. This was the autumn party of four teams plus two pups, with Nick Culshaw & myself, Neil MacAllister and Gwynn Davies, and Malcolm McArthur & Rob Collister which was to return to Stonners over the sea ice by mid-winter. We were plagued by the foot-lurk, and mild conditions so the sea-ice never safely formed. We spent some time at Blaiklock and Horseshoe waiting for conditions to improve.

(Photo: Malcolm McArthur)

Arrowsmith Climbs – Rob Collister

Sledge Sierra (Gwynn Davies and the Ladies, Rob Collister and the Picts)

Diary Extracts

(Photo: Rob Collster)

May 9th – Nearly climbed a mountain today! We are camped on the west side of the Reid glacier by the depot and the weather wasn’t good enough for plane-tabling this morning so we decided to give it a go. We are right at the foot of a spur which is the obvious line so from the tent we only had to cross the floor of the wind-scoop, jumping a couple of small crevasses, and we could start up the first slope of steep, soft snow. Several hundred feet of this, sweating in too many clothes, and a short awkward section where rock and hard ice lay under the snow, brought us onto the actual spur, having by-passed an initial rock buttress.

From there the line was beautifully inescapable. On one side plunged an icefall, a mass of white gouged and chiselled with blue, deep gashes sweeping right up to the crest of the ridge in places. On the other, rock walls dropped away abruptly to a hanging glacier, another chaos of ice. We tiptoed between the two, edging along unstable arêtes and up and down unexpected notches, experiencing no real difficulty but always conscious there was no room for error. Two hours of steady climbing, spoiled only by descending cloud which shut off any view, and our spur joined the broad summit ridge. We moved along it cautiously in decreasing visibility, suddenly exposed to the full blast of a vicious wind.

Two hours of steady climbing, spoiled only by descending cloud which shut off any view, and our spur joined the broad summit ridge. We moved along it cautiously in decreasing visibility, suddenly exposed to the full blast of a vicious wind. We were aware of a cornice but found it difficult through mist and ice-coated specs to gauge whether we were a safe distance from the edge. Cramponing on a hard wind-crust meant there would be no track to follow in descent which was worrying. A serac loomed up and was skirted. Several holes were discovered when we put our legs into them, glad to be on a rope. The angle was easing off and it felt as if we were almost there. But we could see next to nothing and finally discretion proved the better part of valour. Reluctantly, we turned round and groped our way back the way we had come. Halfway down we dropped out of the cloud and could see the pink dot of the tent far below, the howling of the dogs carrying clearly on the wind.

Postscript

Inevitably, the weather next day was perfect, the best we have had since being dropped on the Jones Ice shelf in March. We can see that we were literally 50ft or less from the summit so we are claiming it as an ascent. On my map I’m calling it Mount Dersingham after the village in Norfolk where my folks live but I don’t suppose that BAS will adopt it.

May 15th (with Malcolm McArthur and the Spartans)

Back at the Jones’ for a spell in charge of the animal sick-bay. Seizing the opportunity of a day’s interval between our arrival and Delta’s departure, Malcolm and I today climbed the west face of the large peak on Blaiklock overlooking Scree Cove. This time we had excellent weather, making it one of the most exhilarating, worry-free day’s climbing I’ve ever had. We have been calling it Christmas Pud because of the way snow seems to dribble down it but I think I’ll put it on my map as Mount Sandringham as a sequel to Mount Dersingham.

It was still dark when we left camp but by the time we reached the col above Scree Cove, an hour and a half’s run, the sky was rose in front, saffron behind. It was after 11 by the time we had picketed the dogs and sorted out boots and gear and as we plodded up the first snow slope the sun came down it to meet us. Thereafter it was with us most of the day, only briefly obscured by the bulk of Mount Rendu, and at times we were climbing in shirtsleeves and bare hands. Our route involved straightforward if strenuous step-kicking up a long shallow couloir, on a line left of the summit, until further progress was barred by a continuous ice-cliff. Malcolm climbed a short but steep pitch on rather rotten ice to take us over a weakness in the barrier and onto the summit icefield.

The view down Scree Cove, suddenly revealed, was breathtaking, the long black arm of gleaming water directing the eye to the glowing, golden peaks of Pourquoi Pas. The icefield really was ice and brittle too as we discovered when we tried to drive a peg into it. Fortunately, it was at an angle that made front-points unnecessary but serious ground, nonetheless. Crossing it on a rising traverse we were relieved to hit soft snow and headed straight up, threading a way through a number of donglers, great cauliflowers of sugary snow and rotten ice that are a feature of the mountains down here.

The summit proved to be another of them, like the pom-pom on a ski hat, and we had to climb fifty feet of very steep, unstable snow to reach the top. It gave a final airy flourish to the climb adding to a wonderful sense of space and light all around. It was utterly still, utterly quiet. In every direction stretched mountains and glaciers, intersected by fjords in which leads of open water glinted in the dropping sun.

Far away Mount Wilcox stood out above all else, like a prominent arrowhead, still waiting to be climbed…

But time was short. It had taken us three and a half hours to climb about 3500ft. The descent, after a flurry of photos, took another hour and a half. We were back on the col to a frantic reception from the dogs as the light faded and sledged back to camp in the dark and minus twenties.

May 21st

Lying up today as the wind rose and the mist came down just as we were getting up. Yesterday Gwynn and I climbed the southern of two small peaks at the foot of the Heim’s true left bank, overlooking the Jones’. It’s going on my map as Mount Wolferton to continue the Norfolk theme.

It was very straightforward, about 2000ft of steepish snow with some hard neve at the top. Again we had fine weather, magnificent views and a sun-bathed summit. We were sweating as we kicked steps upward yet the air temperature kept our beards a mass of ice all day.

The hardest part of the climb was sledging to and from the foot of it through a belt of crevasses. When we set off for home my dogs took off with enough force to put a rocket into orbit, as they always do after a long wait. Since we were on a slope I had no hope of holding them with the brake and, unfortunately, instead of following the track in a wide arc round to the left they made straight for Gwynn’s team, already half a mile below.

As a result we thundered straight across the crevasse lines we had so carefully skirted on the way up. While I yelled desperately at the dogs and vainly tried to brake, we opened up one hole, charged across another and then, whoosh, Jet and Yuri were on the far side of a six-foot gap and the trace showed that Morag, who had been leading, was dangling somewhere below. I went forward hoping to lift her straight out but made the fatal mistake of leaving the sledge unpicketed. The other dogs panicked and before I knew what was happening dogs and sledge were careering downhill, leaving me stranded in the middle of the crevasses, forlornly clutching a single ski. I felt not a little foolish.

Patient as ever, Gwynn picketed my dogs when they reached him and drove back up with his team. It turned out that Morag’s harness had broken. I abseiled into the crevasse and found her about 60ft down on a small snowbridge, presumably the snow which had collapsed under her, with a further hundred foot drop on either side. She seemed none the worse for wear, just very pleased to see me! I attached her to a second rope, passing two loops under her stomach, and then jumared out, taking longer than I should have done. By the time I eventually re-emerged it was dark and together we hauled Morag out. Gwynn had driven his team across the crevasse further to the left where it narrowed so that his sledge could act as a bridge if we needed to set up a hoist. The problem now was to bring his dogs back to the lower side of the crevasse without pulling his sledge into it. As I led the dogs around I fell up to my armpits into another crevasse whose existence we hadn’t suspected.

Finally, however, we were once more on our way home, me leading with old Jet up front as he seemed the only dog able to follow the faint trail back to camp in pitch darkness. Troubles never come singly though and, sure enough, I had no fewer than four major punch-ups on the way. The temperatures must be in the minus thirties at night now and we were glad when the tilly lamp and primus were alight and the tent a haven of warmth. An eventful day and more than one one lesson learned the hard way!

Arrowsmith Diary – Rob Collister

6th June – All six of us are ensconced at Blaiklock hut. It is crowded but cheerful with plenty to talk about since we have not all been together for several weeks. A lovely smell of wood and food greets you as you enter the hut, like an alpine chalet. At least it did – it has quickly become submerged beneath other, less pleasant, smells! The nearest equivalent to its cosy squalor that I know of is the CIC hut on the Ben. The weather is bad and the sea-ice is slushy and melting, showing every sign of leaving us stranded. A holiday atmosphere prevails, however, and there are plenty of repairs to sledge equipment and odd jobs about the hut to be done. After living in a tent it is luxurious to be able to stand, sit and move about inside. This evening we had a huge meal of tinned steak and peas with real potatoes which have somehow survived prolonged freezing since I bought them in Stanley, followed by Christmas pudding. At the moment Malcolm is playing his mouth-organ, between tunes helping Brian with a crossword, Nick is splicing a side-trace, Gwynn is mending a harness while Neil is busy making doughnuts to stonker us even further.

11th June – Malcolm, Nick and I have Blaiklock to ourselves at the moment which is very pleasant as we are good friends and the hut is less cramped. We get up at 11 and go to bed correspondingly late and, since the weather is bad, we have been doing a lot of cooking. I have made macaroni cheese, curry, risotto, apple pie and fruit cake with varying degrees of success but all a welcome change from meat-bar! Nick has produced excellent wholemeal bread from a recipe sent over the radio from Stonington. Malcolm is a pancake and drop-scone expert. Unfortunately, the paraffin stove must have been salvaged from the Ark and is temperamental, fumey and not very hot. But beggars can’t be choosers.

One evening we walked along the coast to look for seal since our supplies of Nutty are limited and there is no knowing how long we may be stuck here. Malc took his leader Elphine and I took Morag. They behaved just like pets at home, running on ahead and then rushing back for reassurance. I wouldn’t dare let any of the dogs off here, though. They would come back but in their own good time, probably after rifling the seal-pile and a fight or two.