Summer Surveys in Palmerland – Steve Wormald

Due to the generally unstable sea-ice during the Winter of 1970, it was decided that all the journeys to the southern work areas would take place via the Antarctic Plateau. This meant using the only viable access route to the Plateau, the infamous Sodabread slope, 3,000’ feet of snow, ice, and known for its katabatic winds that could spring up, even on clear days, in a matter of minutes.

Our 1970/71 Geology party, using radio call signs Sledge Sierra (Gwynn Davies and Rod Pashley) and Ali Skinner and myself as Sledge Tango, planned to travel overland to Quintin Depot, established the previous summer. The first step was to establish a food depot, 28 days of manfood and dogfood, at the top of Sodabread on the Plateau edge, which was accomplished over three days without any serious incidents, in good weather.

Continuing from Stonington Page…

That done, we returned to Stonington, loaded up in anticipation of a six-month long Summer journey, and traveled the 14 miles back up the Northeast Glacier to Sodabread on the 3rd September.

We had an abortive start the next day, as wind and heavy drift sprang up, not good conditions to be caught halfway up the route. We tried again the next day, leaving the tents standing at the foot of Sodabread, and ferried one set of loads to the Plateau edge, returned to the campsite at high speed, packed up camp and ferried our second loads to the Amphitheatre, a feature halfway up Sodabread that typically offered some respite from the katabatic winds. We were stuck in the Amphitheatre the next day, although we did pack up camp, only to have to pitch the tents again in a 40 knot wind and heavy drift again.

The whole next day we were beaten up by 30-50 knot winds, but finally, on the 8th September, we were able to ferry the last loads from the Amphitheatre to the Plateau Edge, and continue on the six miles to the first food Depot at Armadillo Hill, carrying loads of 600/1,000 lbs., where we camped in strong winds and drifting snow again.

The first 23 miles had taken six days, and the journey from Stonington to Quintin Depot, where our next food was depoted, was 196 miles, so we still had 173 miles to go. Because of the soft snow surfaces, we averaged only 6.9 miles each day over 18 traveling days, with 8 days of “lie-up” in bad weather that made travel impossible, and two days waiting as two of our bitches had their pups (which then had to then be culled).

In deep soft snow, no dog team could be expected to break a new trail and pull a loaded sledge. In an attempt to keep four teams traveling at about the same speed, the lead sledge would be lighter in load, making it easier for the dogs to break trail. Under these conditions the dogs would pull their loads at about 4 miles per hour. Exceptions happened, where crevasses were unexpectedly encountered, or where it took six days to travel 10 miles of eight to ten hour days of pushing, pulling, generally struggling, before collapsing into the tent, exhausted.

Each Geology party had 90 days food depoted at Quintin, and a further 30 days each at Ball Point (in George VI Sound) , which had been re-stocked during the winter by Fossil Bluff personnel.

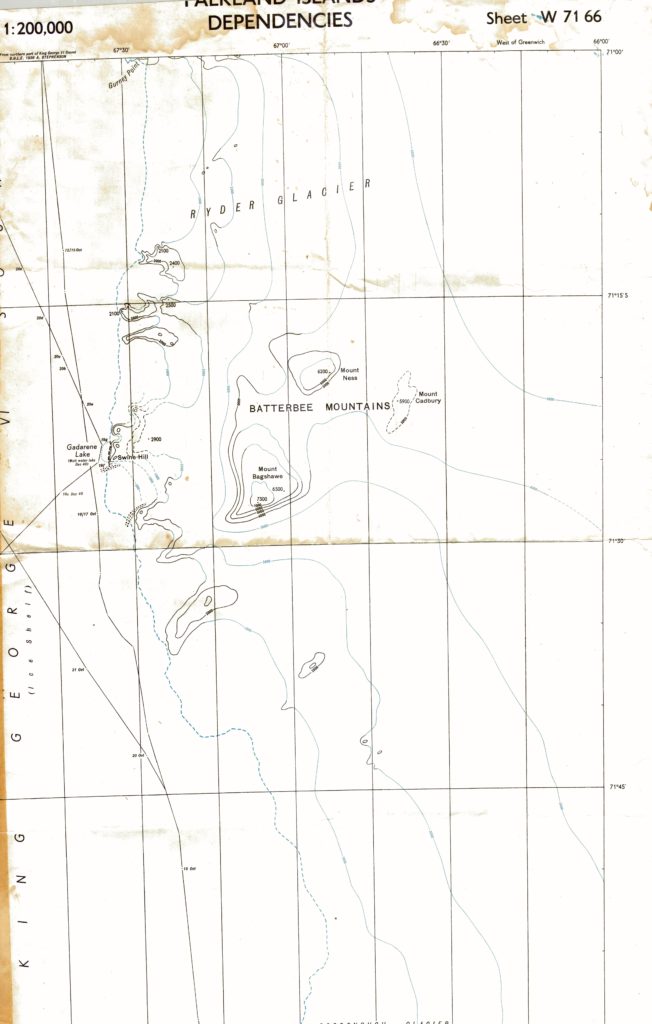

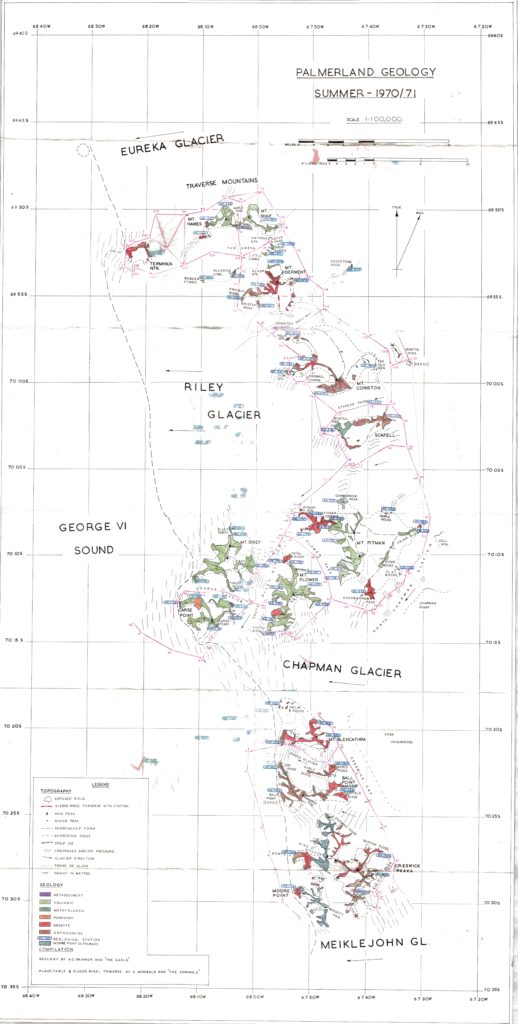

Eventually, after almost a month of travel, we reached our work areas, and an altitude and time of year where conditions began to improve and traveling became easier. We began the geology work programs, in our case South of the Eureka Glacier, as far as “Creswick Peaks”, using all the Ball Point food and some from Quintin, while Sierra worked the area north of the Eureka and East in the Fleming Glacier, using Quintin Depot solely. Both parties were planned to be re-supplied by the aircraft towards the end of the season.

All this area was virtually untraveled by any other sledge parties since work began in 1936, and so the detailed geology work allowed us to visit many previously untraveled areas and places.

Existing maps were almost blank, and we were in a beautiful area with mountains, nunataks (rocky outcrops) and untraveled glaciers, so it was my task and joy to give everything a name so that Ali could locate his geological specimens, on the maps I prepared using a plane-table and a bicycle wheel. I used features exclusively from the English Lake District on the map, of which, many years later, none were adopted by the all-powerful Antarctic Place Names Committee!

The work went on for weeks, with mostly good weather (at least as I remember it many years later), where Ali with the Gaels would head off to the next outcrop and the next, and myself and the Admirals would carry on the plane-table mapping of the peaks and nunataks, and establish the locations on the map for each of Ali’s rock specimens.

Occasionally we would get into trouble with our teams and have to haul one or more of the dogs out of a crevasse, but generally, sledging was routine and efficent, for both ourselves and the dogs, who were now quite happy to go for a run with a light sledge, and then sunbathe between runs.

Fom time to time, we would load up and move camp to another locations closer to where we were working, at which point to dogs had to work again, or make a run to a depot to offload rocks and pick up manfoor,, dogfood and fuel.

On our first aircraft re-supply trip I had arranged to have two replacemement dogs sent in. These were to replace ‘Gloin’, whose age and arthititis were causing him some problems in the summer sun and faster pace of the team; and ‘Twisty’, who on the southern journey from Stonington had got himself into trouble and had his anus ripped apart before I could stop the fight.

I carried out several stitching sessions, but none were successful, his sphincture muscles were not performing, and he constantly dropped poop on the trail. All dog team drivers know the problems with dog poop, a major hazard as it stuck onto the sledge runners, and then froze, and had to be removed or the sledge ground to a halt, not easy with a loaded 1,200lb sledge.

So I was delighted when I was offered ‘Sam’ and ‘Kirstie’, that I had helped rear as pups at Adelaide a year earlier, and after the usual training and being beaten up by Big Jim, Dai and Waldo for a few days, they settled down to be great working dogs.

Steve Wormald, Met – Adelaide, 1969, GA Stonington 1970 & 1973.