The Cross-Wordie Lines – Tim Christie

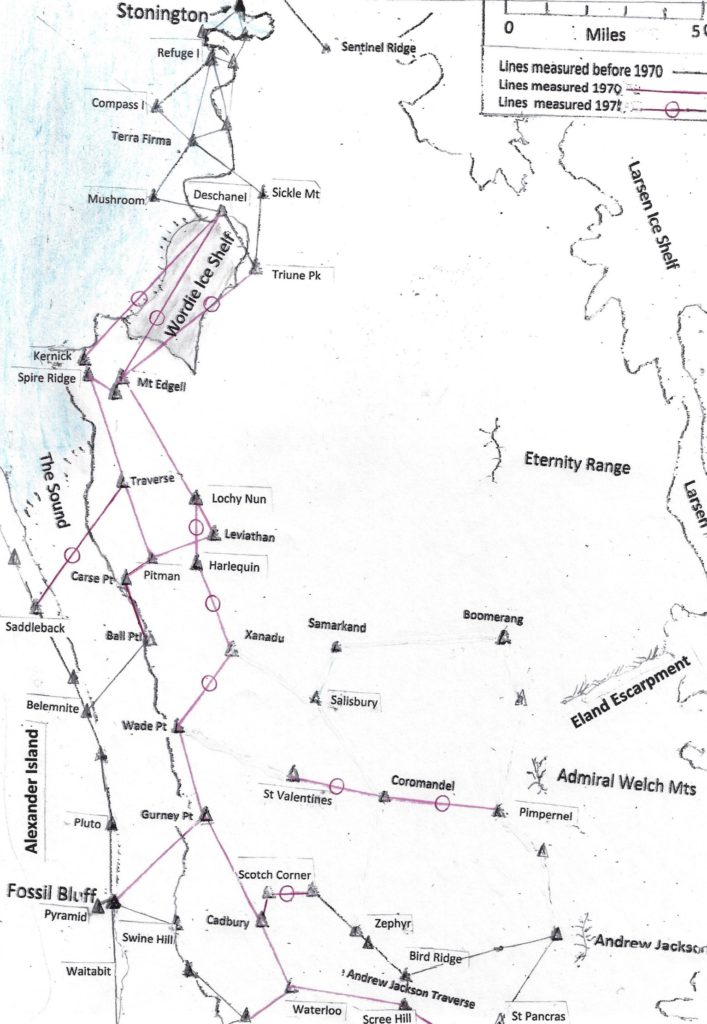

When we arrived at Stonington in March 1970 the main task we had been given by the DOS was to make a survey connection between Stonington to Fossil Bluff with an unbroken chain of tellurometer lines. Up to that time, although some survey had been done from Fossil Bluff, this was a ‘floating” survey with no connection to the survey network on the rest of the Antarctic Peninsula the surveys from Stonington having only come as far south as the Wordie Ice Shelf at Latitude 69 deg S.

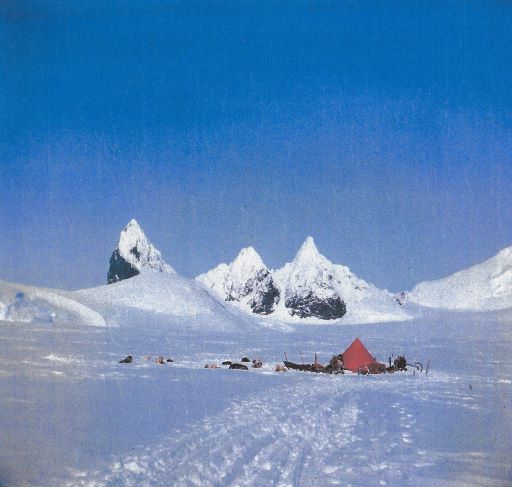

We thought that measuring the first three tellurometer lines across the Wordie Ice shelf might cause us some problems, partly because of their length, partly because of the logistic difficulty of getting the two survey teams on the opposite side of the ice shelf at the same time and partly because the north and south sides of the Wordie were in different weather systems. What we didn’t expect was the crisis that arose every time we were about to measure the lines.

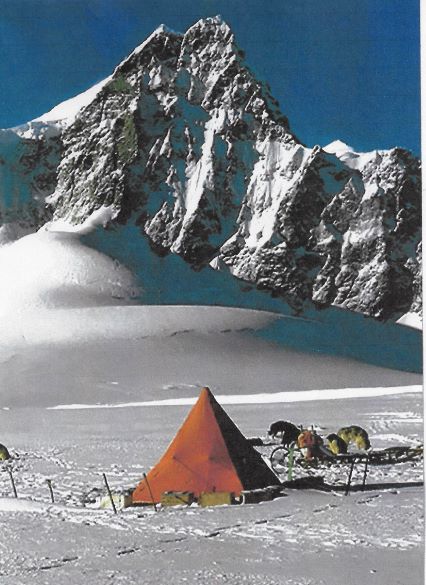

By September 26th 1970 the three of us on Sledge Oscar (that is Richy Hesbrook, Henry Blakely and I) had sledged south over the plateau from Stonington (because there was no sea-ice), crossed the Wordie Ice Shelf, established a new survey station on a spur of Mt Edgell and were ready to measure the first line across the ice shelf to Triune Peak which Paul Bentley and Sledge Alpha had just reached, when he radioed us to say his tellurometer wasn’t working. ( This was a tellurometer he had had to abandon on the Terra Firma Islands the previous year when the sea ice started the break up and they had to sledge off as quickly as possible without loads to avoid be marooned there for a year). We had recovered the tellurometer the following spring and left it on a depot at Deschanel to be picked up on our way south at the start of the season, but for some reason it had not survived its year in isolation and was not working, and we had no alternative but to abandon measuring the lines for a while.

Paul Bentley had however made radio contact with Fossil Bluff where they had a spare tellurometer and they agreed to leave it at the Ball Point Depot, 80 miles south, on the edge of the Sound for Paul to pick up, and we agreed to meet him there so we could measure some tellurometer lines on the way back north to the Wordie.

We had to re-arrange food depots to cover this change of plan and it was a month before we met up with Paul and his replacement tellurometer at Ball Point. We then started to work our way north back to Mt Edge” measuring five tellurometer lines en route to connect the existing Ball Point trig with the new Mt Edgell Stations. However, we had just measured the second of these lines when I inadvertently let my tellurometer roll off the Carse Point survey station and go bouncing down a 400 ft cliff at considerable speed.

My diary recalls:”…When I turned round the tellurometer had just taken its first bound into spacwas splitting itself on the next jag of rock. In this way it continued to bound down the gulley — now at considerable speed sometimes ricocheting from side to side, at others bouncing high jnto the air and smashing itself on the next jag of rock. On the final bounce the front cover sheared off and the tellurometer, the reflector and the delicate dipole crashed separately onto the scree. I was aghast— more concerned at the disastrous effect the destruction of the tellurometer would have on the year’s survey programme than the fact that I had just lobbed something as expensive as an E-Type Jaguar off the top of a mountain!”

It would have been the end of our survey season before it had hardly begun had Ali Skinner and Steve Wormald not, by chance, been camping with us that day at the bottom of the cliff.

“Let’s connect up the bits and see if anythings working” Ali said when we showed them the wreckage, and as they did that, to my amazement a little green light suddenly lit up. Although the tellurometer was clearly totally unusable, there were however parts that somehow were still working and Steve and Ali went on testing them until, eventually, much to their surprise, they found that the power pack was not damaged.

As the rest of the tellurometer was unusable this would not have been much help, except that we knew that it was the power pack on the tellurometer that Paul Bentley had abandoned at Ball point that was faulty, and that if we could recover his tellurometer and swop its faulty power pack with one from our ruined tellurometer, our survey season might yet be saved.

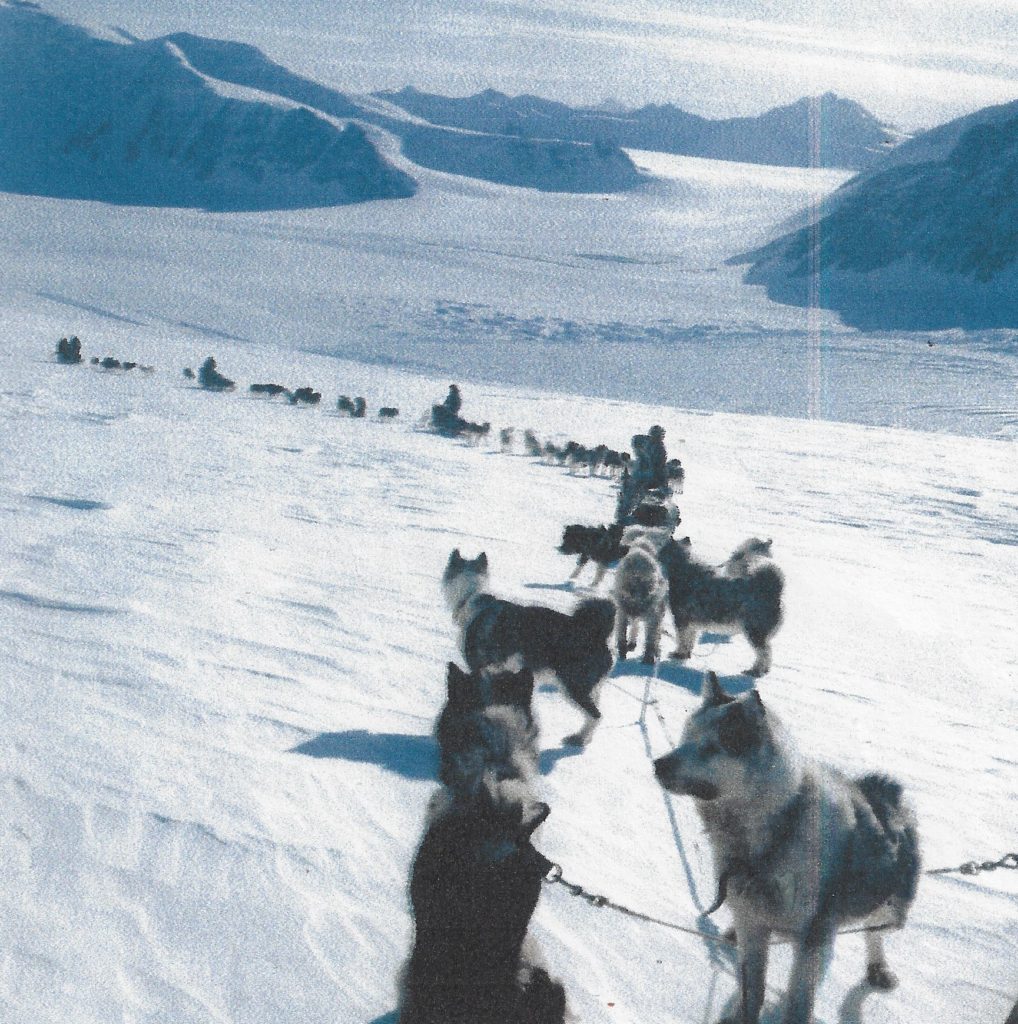

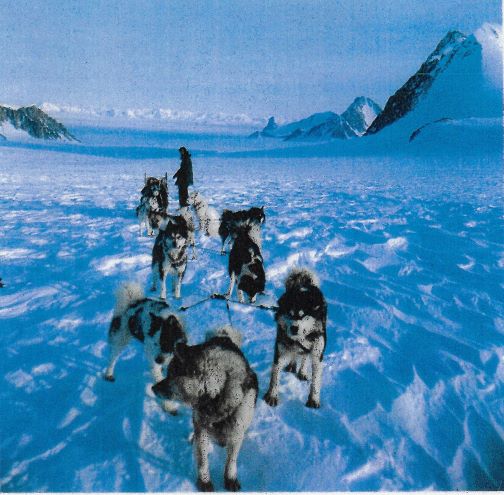

So although it was late evening, Richy and Henry harnessed their dogs and set off to Ball Point, arrived back the next morning after a 30 mile journey with Paul’s “abandoned” tellurometer, passed it to Ali Skinner who changed the power packs over and miraculously I had a working tellurometer again.

Although we then returned to Mt Edgell , Paul Bentley decided it would be best to concentrate this year on measuring the lines from Mt Edgell down to Fossil Bluff and to leave the measuring of the Cross-Wordie lines until next year.

But the initial attempt to measure the Cross-Wordie lines the next year (1971) was even more disastrous than it had been in 1970. I had had a good journey south over the plateau with my new GAs, Miles Moseley and Drummy Small and we were camped at our Edgell Spur Trig waiting for Sledge Charlie (Paul Gurling and his GA, Paul Finnegan) to occupy the trig stations on the other side of the Wordie when we received a radio message from them saying that when they went to the Castro depot to get food they had left all their survey equipment on the Harriot Glacier, and when they got back they found that the whole lot had been blown away – by “winds of unimaginable force” tellurometer, theodolite, generator, batteries, signalling lamp and even their expensive personal cameras.

This was even more serious than last year. Now the Cross-Wordie lines, our whole summer’s programme, if not our whole two years’ work in Antarctica was in ruins. We had sent a spare tellurometer down to Fossil Bluff by plane the previous year for just such an emergency, but replacing the theodolite and the rest of the equipment was just as important and we knew that Martin Pearson and Ian Rose (the current residents at Fossil Bluff) were 200 miles

away geologising at the southern end of the Sound anyway.

When I radioed Martin Pearson he was most helpful and said he could lend us their spare theodolite and at least some of the lost equipment but that they still had several days’ work to do down the Sound. He thought though that he could meet us at Carse Point in about a fortnight, if we could then escort them through some difficult pressure ice into Alexander Island to do some glaciology (dogs being safer than machines when negotiating dangerous pressure).

It took us a nearly a fortnight to get down from Edgell to Carse Point. Paul Gurling and Paul Finnegan arrived five days later and when the Fossil Bluff crew heard that they had arrived there, they immediately left and “drove” up to join us travelling 60 miles overnighte The two Pauls then set off back to the Wordie with their replacement survey gear whilst Drummy, Miles and I accompanied the Fossil Bluff caboose and skidoos across the Sound to Alexander Island.

We had always hoped that we would somehow be able link our West Palmer Land survey lines to those on Alexander Island, with a tellurometer line across the Sound. Now with us on Alexander Island on one side of the Sound and the two Pauls heading northward on the other, the opportunity was too good to miss. So when we heard that they were at our last year’s Traverse Mountains survey station, we climbed up to the Saddleback trig on Alexander Island and measured the very valuable tellurometer line across the Sound.

Next day we descended and headed back across the Sound to Carse Point. Drummy’s ankles had been troubling him so much that he couldn’t really drive a dog sledge, so he agreed to join the Fossil Bluff team and to let Paul Burton take over his dog team for a while. (Drummy was to rejoin us some weeks later).

A day or two later we were heading up the Ryley Glacier onto the plateau on the way back to Mt Edgell. We hadn’t heard from the two Pauls for a couple of days but we were hopeful that they were now descending onto the Wordie Ice Shelf en route for the survey stations on the other side, and that they would be there by the time we reached the Edgell Spur Trig. Imagine our horror therefore when, as we reached the top of the Riley Glacier we saw two sledges far below us heading southward— unmistakeably the two Pauls.

When they saw us they changed direction and came up to join us.

“The ultimate spon” Paul Finnegan said, “Our radio has had it. It’s completely dead, we will have to go down to Fossil Bluff to get another”.

“What’s wrong with your radio?” Paul Burton asked. “Haven’t you looked inside it?”

“No, the radios are all sealed with 12 bolts that need a special Allen key to undo them”.

The resourceful Paul Burton then rummaged through our Primus spares until he found a Primus nipple extractor, and he then spent nearly two hours filing it down until eventually it fitted into the heads of the bolts and he was able to open the radio.

“Looks as if they’ve had a ruddy bonfire inside it” he said.

Fortunately though, none of the critical components had been damaged and after Paul Burton had done some re-wiring the radio crackled back into life. Saved again!

(It was a nice coincidence that Paul Burton who had just saved our 1971 survey came from the same Yorkshire village as Steve Wormald who had helped Ali Skinner save our 1970 survey programme).

This wasn’t quite the last of the Cross-Wordie crises because while crossing back over the ice shelf Paul Finnegan damaged himself falling down a crevasse and Paul Gurling dropped his whole dog sledge down one.

And then: just as we had set up our tellurometers on the two sides of the Wordie Ice shelf and were at long last about to measure our first Cross-Wordie line, Paul Gurling radioed to say his tellurometer wasn’t working. We did however find a miraculous way of overcoming this serious technological problem although it took all night to discover. The method was: using another battery!

So: unbelievably, on November 30th, exactly one month after leaving Carse Point, we had measured all three Cross-Wordie lines in both directions.

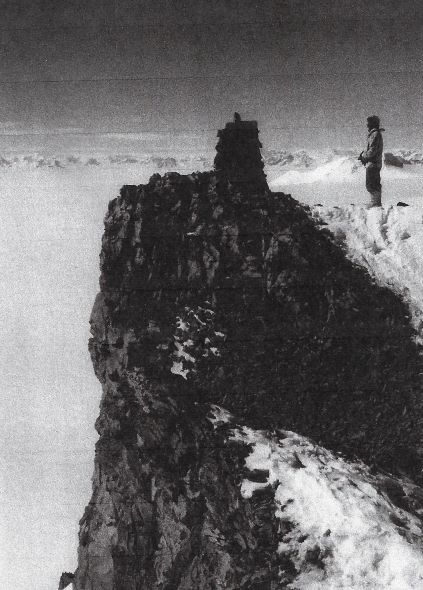

On the last morning we could even see Paul’s heliograph at Triune Peak from Edgell Spur with the naked eye — 40 miles away. It was when I was on the Edgell Spur Trig that I suddenly wondered if I could see Grandstand, the survey station we had established on Butson Ridge near Stonington the previous autumn. I wasn’t very hopeful, as I knew the trig was over 105 miles away, but when I looked through my theodolite, to my surprise I could see it. So I measured an angle to it — more or less as a joke, as I thought no one would believe that you could see a four foot wide cairn 105 miles away even through a theodolite!**

** – I was lucky that we had measured the angle to Grandstand from Edgell Spur 105 miles away, because when I was back at the DOS in London the next year computing the Stonington to Fossil Bluff traverse, the computer operator came and told me that there was an error in one of the angles that had been measured on the traverse and that although they had enough information to complete the traverse calculation if they knew where the error had been made, at the moment they had two solutions, Option 1 and Option 2. I then remembered the “joke” angle I had measured from Edgell Spur and gave him that to add to his computations. The next day he returned and told me that using Option 2, the angle I had given him was correct to one second of arc that is the width of a pencil at a mile distance. So the Stonington to Fossil Bluff traverse was saved again.

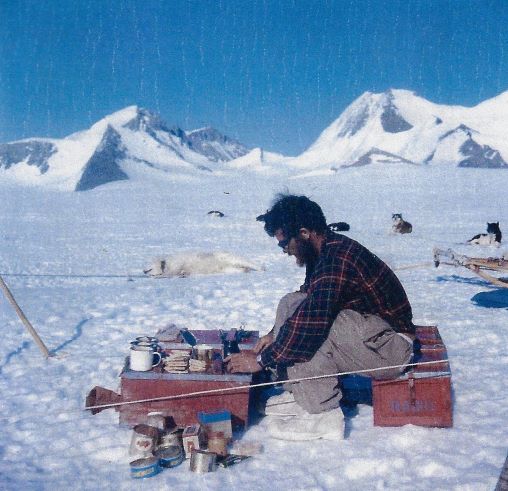

(Photo: Tim Christie)

When the calculations on the Stonington to Fossil Bluff closed-loop survey were finished, with all the corrections for latitude and earth curvature included, it was found that the 500 mile long traverse closed to within a metre.

Once the Cross-Wordie lines were measured and Sledge Charlie was back on the ice-shelf, the remaining lines on the Stonington to Fossil Bluff and Fossil Bluff and the 1964 Andrew Hackson Traverse traverses were completed by the end of the year before and we spent the remaining time before the Bransfield returned establishing survey stations high on the centre of the Palmer Land plateau (Coromandel, Pimpernel, Boomerang and Samarkand) which would allow (in future years) the existing surveys and uncharted mountains along the east coast to be connected survey-wise with our now completed Stonington to Fossil Bluff survey.

Tim Christie – Surveyor – Stonington, 1970 & 1971