The United States Antarctic Service Expedition (USASE), 1939-1941

(All Photos are Courtesy of www.USAS1939.org and the US National Archives unless otherwise stated. )

This story aims to tell a detailed account of USASE, and is based on materials extracted from Kenneth J. Bertram’s book “Americans in Antarctica, 1775 – 1948”; including from research and a paper written by Keith Holmes, modified to suit the MB website format; and was created in conjunction with the webmasters of the US Antarctic Survey Expedition website, and including the help and approval of the US National archives. The USAS1939.org website is curated by Laura Snow, (daughter of Ashley Snow – USASE Pilot), and John Dyer (son of James Glenn Dyer – USASE Surveyor/Cadastral Engineer).

In addition, the story “The Dogs of East Base”, sent in by Neil Marsden (Surveyor, Stonington, 1965 & 1966) , relates in detail the sad story of the USASE dogs at Stonington in 1941. Neil was intrigued by a paragraph in Jenny Darlington’s book, “My Antarctic Honeymoon” plus a brief sentence in Kevin Walton’s book “Two Years in the Antarctic” relating to the dogs of the USASE in 1941.

Further research by Neil Marsden unearthed the comprehensive report by Joan Bryner. This is quite a long report and worth persevering with; however the evacuation of Stonington begins on page 37 and details the fate of the dogs – Read on HERE“

Neil has continued to research some of the contradictions and additional detail for this story, using Kenneth Bertrand’s book which thankfully he had in inventory at Polar Books (shameless plug: “www.polarbooks.net” a rather good website for books on chilly places“), and these are being added to the story below. The sections below with blue text indicate additions or amendments to the originally published web page.

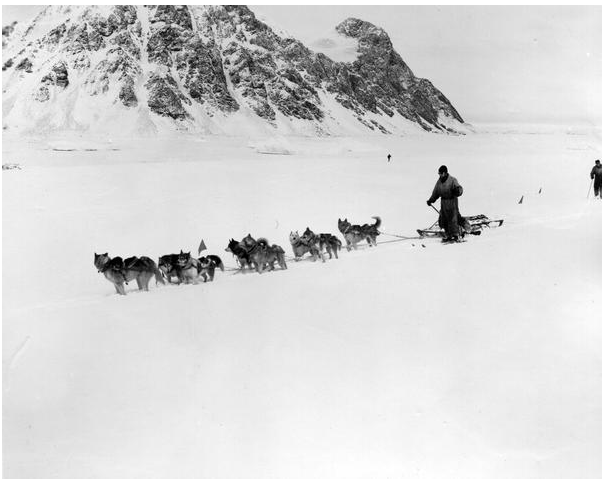

The USAS expedition (“USASE”) carried out important work in the early exploration of the Marguerite Bay and Plateau area, prior to Fids opening up Base E on Stonington. There equipment included a Curtiss-Wright “Condor” biplane, a light Army tank, a light artillery tractor, and seventy-five dogs.

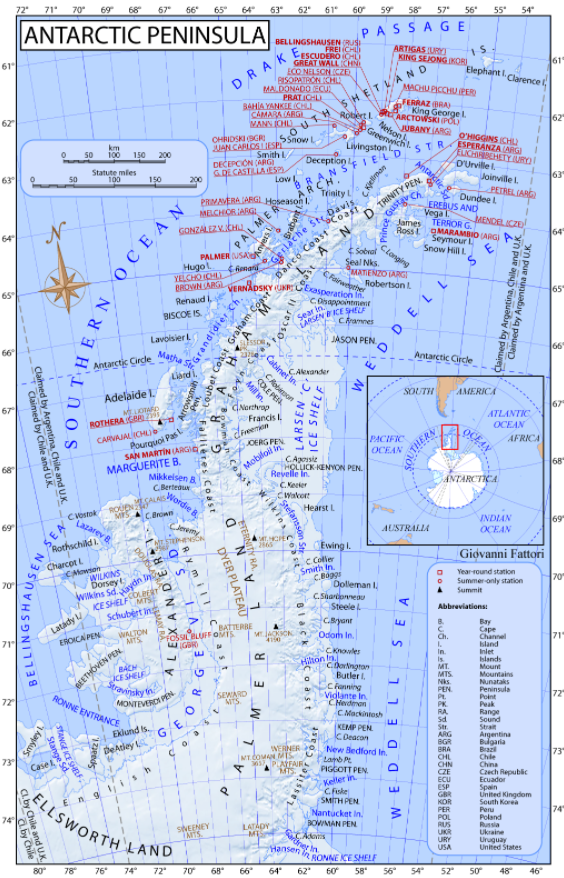

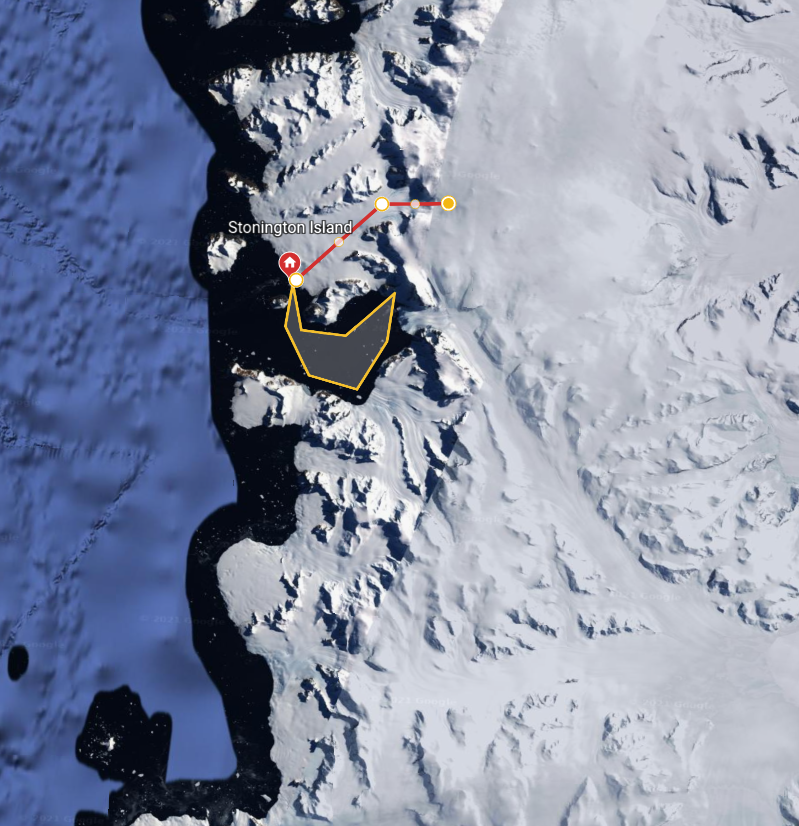

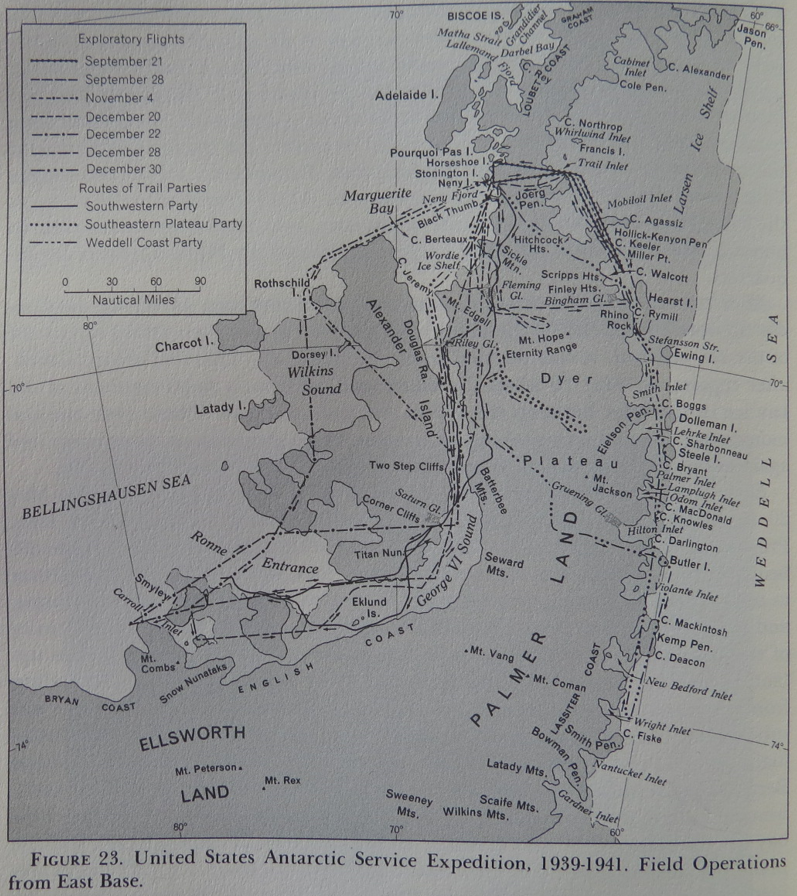

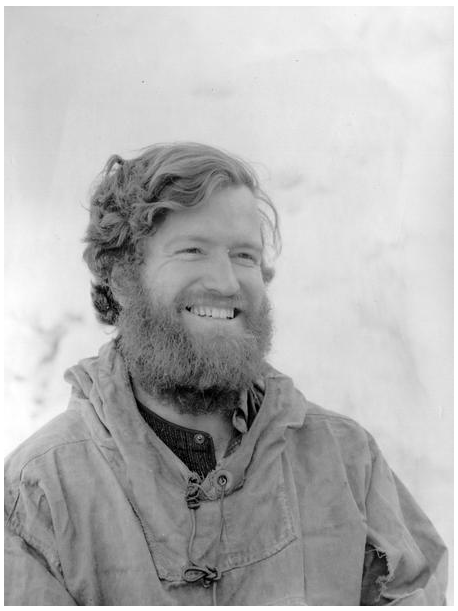

The expedition was staffed by twenty-six men, all employed, in one way or another, by the United States Government, listed below together with the place-names which commemorate their participation, most of which are shown on the map below. Also named were Cape MacDonald, after the Secretary of the Expedition, Bills Gulch, after a lead dog which died there, and (much later, in 1977) the Condor Peninsula, after the aircraft which served them so well.

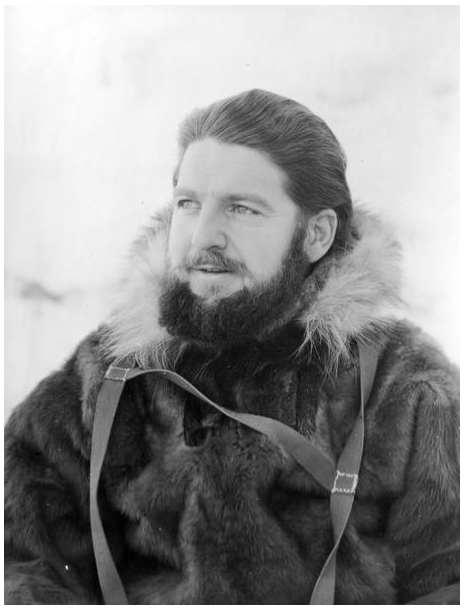

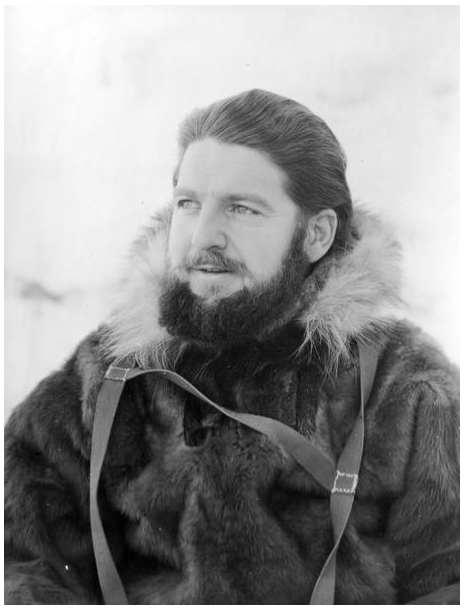

The Leader of the East Base, Commander Richard B. Black, of the United States Naval Reserve, had served as a surveyor on the second Byrd Antarctic Expedition, 1933-35, together with Finn Ronne and Joe Healy.

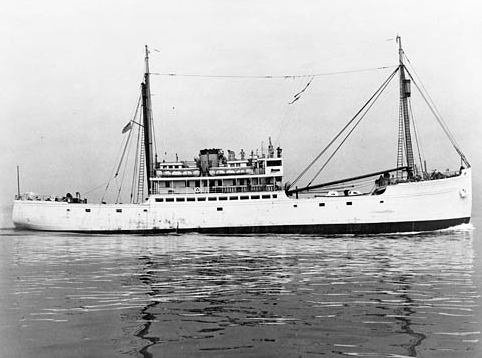

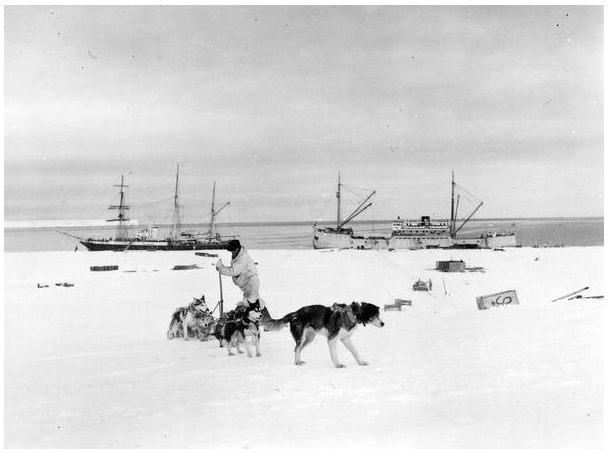

The USAS expedition (“USASE”) was commissioned in November, 1939 by U.S. President Roosevelt, designating Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd, USN, as Commanding Office of the United States Antarctic Service, with a budget of $350,000. together with two ships being made available to USASE, the USS ‘Bear’ and the USMS ‘North Star’. The commissioning letter can be read HERE

Early in 1939, a note in the Polar Record indicated that the proposed American expedition would focus on the coastal sector of Antarctica between Longitudes 75˚ and 150˚ W. The expedition began when the two ships, the US Motor Ship ‘North Star‘ under Captain Isak Lystad and the USS ‘Bear‘ commanded by Lieutenant Commander Richard H. Cruzen, USN, set out from Boston, Massachusetts, USA, on November 15th and 22nd, 1939, respectively, carrying thirty-two named men bound for a West Base near Little America and twenty-nine named men heading for an East Base in western Graham Land. Three clear objectives were scientific work, geographical exploration, and territorial occupation.

A few months later, it was reported that East Base had been established near Neny Island, that Admiral Byrd was directing operations from Washington, and that the expedition was likely to last two years. Congress later rejected appropriations for the second year on grounds that they were inappropriate during a world crisis.

(Keith Holmes – “Black introduced the results of the Expedition’s scientific and exploration programme in the first of several papers published by the American Philosophical Society in 1945. Carroll and his photographs also contributed significantly to the United States Hydrographic Office’s 1943 Sailing Directions for Antarctica. Unfortunately, the entry of the United States into the Second World War meant that very little extra information was ever published by its participants, and, apart from a thorough review by Bertrand, the expedition never received the full attention that it might otherwise have earned. Nor, alas, do any private accounts, apart from that of Finn Ronne, ever seem to have been published. Official archive material was placed in the National Archives, but personal material was generally dispersed and is mostly untraced. Jenny Darlington recalled having seen the comprehensive field diary which Don Hilton kept, but was unaware of its location. John Dyer has the diary of his father Glenn Dyer.”

In his autobiography, Finn Ronne described how his father, Martin, had sailed with Amundsen and wintered with Byrd at Little America. Ronne himself had been influenced from an early age by his father’s example, and by exposure to the achievements and personalities of expedition leaders such as Amundsen, Charcot, Wilkins and Ellsworth. As a result he was thrilled to join Byrd’s second Antarctic Expedition of 1933-35 on which he proudly followed in his father’s footsteps and learnt polar crafts such as dog-sledging.

On returning from that expedition, Ronne was determined to launch one of his own to the unexplored region east of the Little America, starting from a base to be established on Charcot Island, probably in October 1937. By May, 1935, he had already secured the use of about thirty huskies from Seeley’s Chinook Kennels in New Hampshire, and was intent on securing transport aboard Norwegian whaling vessels. He had floated the idea with Richard Black, a former colleague at Little America, who then raised the idea with Ernest Gruening in the Department of the Interior. He in turn raised it with President Roosevelt, who favoured the use of the American fleet and suggested that Byrd and Ellsworth be invited to organise the expedition under the auspices of the United States Antarctic Service Expedition.

Ronne was utterly non-plussed “Before I could discern exactly what was happening, I lost control of my own expedition.” Even worse, when Byrd “invited” him to join it, Ronne was given the choice of serving either under Paul Siple or under Richard Black.

(Keith Holmes – “Years later Ronne barely concealed his disdain for Byrd, having witnessed the fiasco of the Leader’s solo winter “stunt” at an outpost remote from Little America, his sharp-suited appearance, and his somewhat indifferent man-management skills. Nor did Ronne have a very high regard for Richard Black, his future Base Leader, whom he insolently dismissed simply as “the surveyor”. It is puzzling that Ronne had earlier floated the idea with such a man whom he seemed to dislike and distrust so much. His reflection thirty year later was that “As is so often the case when ambition outpaces ability, influence was the determinant.”)

After the event, Polar Record gave an unusually full account of the expedition (prepared under the direction of Paul Siple, the Leader at West Base) in which it recorded that the original intention of setting up East Base on Charcot or Alexander Island had been frustrated by ice conditions and that the expedition’s two vessels, Bear and North Star, had instead met in Marguerite Bay on March 3rd, 1940, to establish a base there.

The ‘Bear’ was already a wonderful old vessel which, Ronne reported, had somehow been recently refurbished at the expense of the US Navy, was now also staffed by the Navy and yet was owned by, and leased from, Byrd as his flagship (which Ronne says he used only once). Another source states that Byrd sold the ‘Bear‘ to the Navy for one dollar.

In his unofficial account of the events, Ronne described how the two ships met at Horseshoe Island (on March 5th), and “drifted aimlessly in the bay. No effort was made to locate a suitable site for East Base…. Unable to remain passive about our situation, I took the initiative and suggested that a few of us go ashore and examine a snowy plain I had spied; it might prove to be an adequate location for our base.”

By contrast, Black commented that he and Admiral Byrd chose the site during a reconnaissance flight on March 8th, with emphasis on it having access to a suitable airstrip on the Northeast Glacier. No mention was made of the earlier discoveries of the BGLE, or their South Base on the nearby Debenham Islands, and in fact Rymill and his team never seemed to have thought of this unmentioned glacier and its adjacent, but also un-named, island as being a gateway to the plateau. However, it is likely that the Americans had been able to observe the scene from a far greater height than the BGLE could reach.

A more precise, but succinct, account of the events was recorded in the logbook of the flagship, Bear. This records her arrival in Marguerite Bay first thing on Monday, March 4th, 1940. That morning the captain searched unsuccessfully for an anchorage off Red Rock Ridge, and in the afternoon moved to the safe site which the BGLE had charted at Horseshoe Island. The following day George Dufek, the ship’s navigational officer, and Arthur Carroll took off in the Barkley-Grow seaplane, first to locate the approaching cargo ship ‘North Star‘, and then to reconnoitre south of Red Rock Ridge. On March 6th, still in strong winds, Dufek took the ‘Bear‘ north to Lagotellerie Island and south to Red Rock Ridge, searching for an anchorage and landing site, and at times mooring alongside the fast ice. Early in the morning of the 7th, both vessels were anchored off Neny Island. An ice party from North Star later came aboard, and after that a motor boat set off with Black, Ronne, Knowles and others, interestingly including two of the four representatives from the Argentine and Chilean Navies. Nothing was reported of the findings and the ship spent the night back at Horseshoe Island.

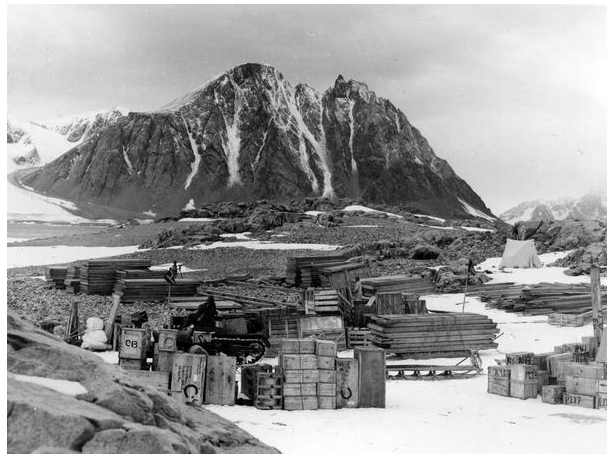

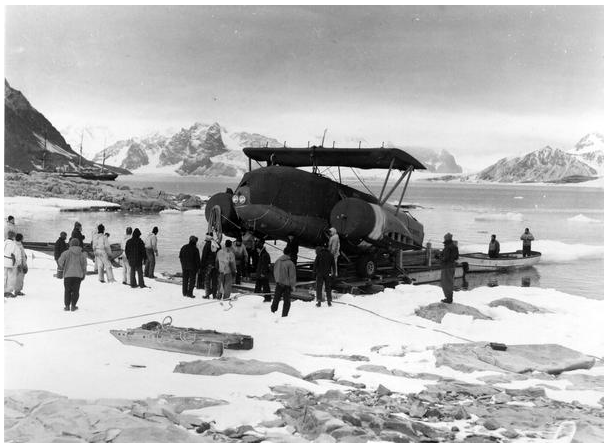

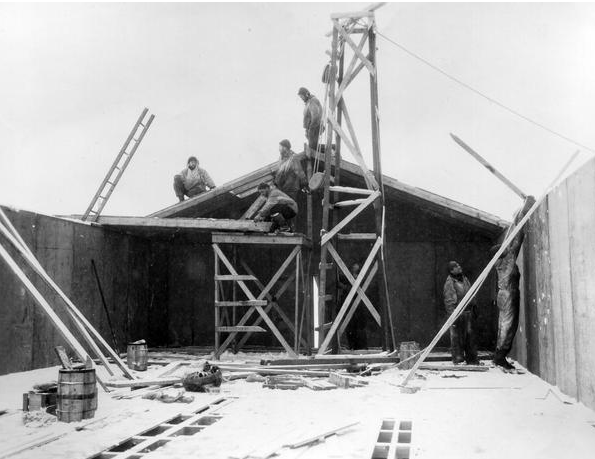

The only events reported on March 8th were the shifting of the anchorage to undertake more soundings, and a flight by Byrd in the Barkley-Grow T8P-1 sea plane specifically assigned to the ‘Bear’ for ice reconnaissance. The next day was spent even less eventfully at Horseshoe Island cove, but on the following one, before the winds rose again, the crew set marker buoys and lights in the Cove. The following day the crew landed on Horseshoe Island during a lull in the gales. ‘North Star‘ had meanwhile been anchored off Neny Island and started unloading on March 11th. At last, on March 13th, ‘Bear‘ was moved to join her, and four men were transferred to North Star and then assigned to East Base. ‘Bear’s’ cargo was unloaded the next day and men helped to take the Condor aircraft ashore from ‘North Star‘. Strong wind forced the Bear to anchor again at Horseshoe Island from the 14th to the 18th and cease unloading, but a lull allowed the crew at least two recreational visits to the penguin rookery on Lagotellerie Island. James F. Wiles, a maritime engineer aboard ‘North Star‘ also found a recreational outlet in climbing Neny Island for the first time.

Next, there was trouble with ‘Bear’s’ main engine but on the 20th, the vessel returned to Neny Island and moored alongside ‘North Star‘ to transfer fuel. The last of the shore staff were transferred on the 21st and both ships set off for Valparaiso.

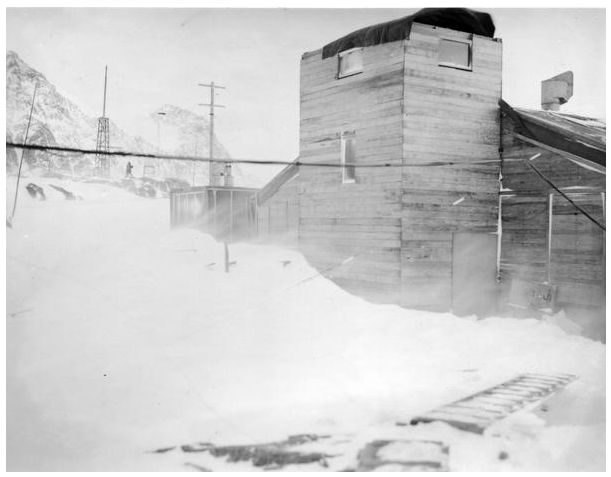

(Keith Holmes – “Finn Ronne claimed to have organised the construction of the various buildings which the expedition had brought, in prefabricated form, from America. Thanks in part to an excellent description of the site in 1976 by visiting geologist Jere Lipps, it later became an official Historical Monument under the Antarctic Treaty. The buildings, and much of the associated stores and equipment, were conscientiously documented many years later during a professional archaeological survey of the site as part of the listing process“.

Black had concluded from the BGLE’s experience that it would be unwise for any southern sledging party to expect the sea-ice to permit their easy return to Stonington during the summer, and he was thus keen to find a plausible route along the western side of the peninsula. Furthermore, he noted that Rymill had crossed the plateau in latitude 69˚ 50’ S, and “had stated that it would be impracticable, if not impossible, to cross the peninsula north of his crossing.”

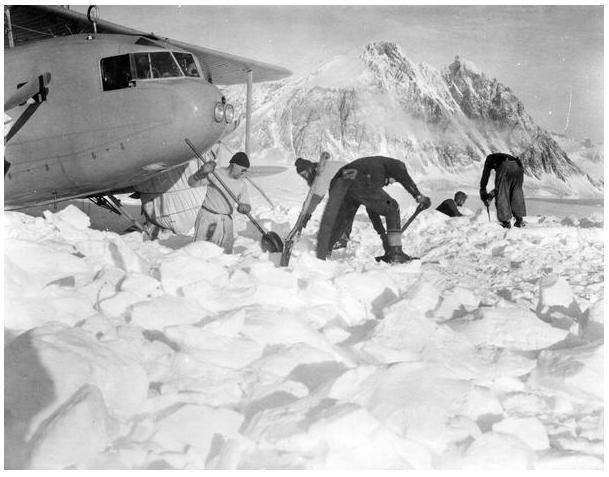

Nevertheless, Black wanted to find another route over the plateau so that he could explore the eastern coast. He started a programme of aerial and sledging reconnaissance soon after the main living hut was first occupied, on March 27th, and the aircraft had been assembled. After unsuccessful efforts to haul the latter up to the glacier by tractor, it was flown directly from the island to a landing strip marked out on the glacier a mile or so from the base. A small hut placed there at this time, made from the crate of the Condor aircraft, was still evident in 1946.

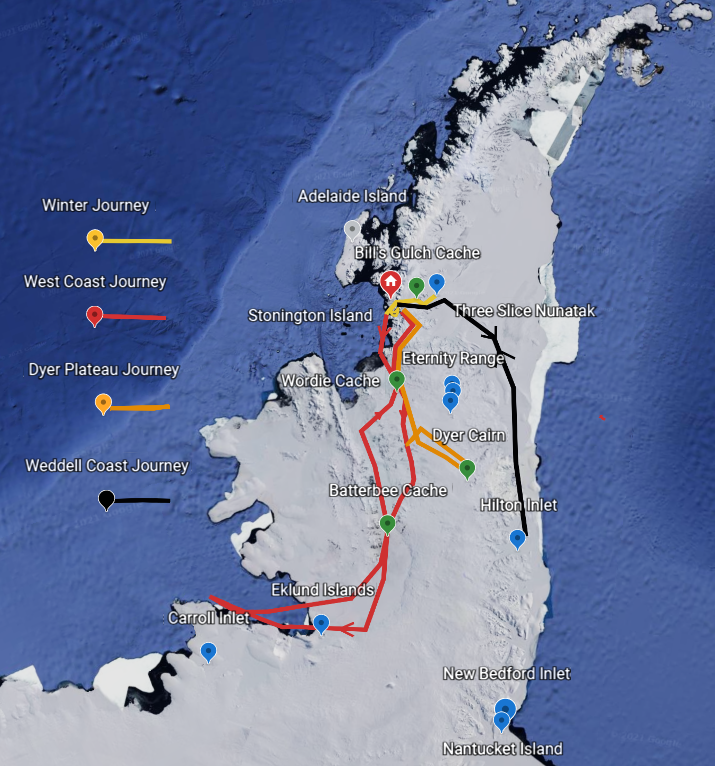

On May 20th, 1940, pilots Snow and Perce took Black, Carroll, Ronne and Dyer on their first reconnaissance flight from Stonington Island to the northern entrance of George VI Sound. This allowed the field party to take photographs of possible sledging routes and choose the site for a depot of food and supplies which Snow and Perce placed the next day with Don Hilton as observer. Black recorded that this, their Wordie Cache, was laid at a height of about 2000 feet, at a site with co-ordinates 69˚ 32’S, 66˚ 56’W. It was near the Relay Hills in a location recognised from the work of the BGLE as being suitable both for an easterly crossing of the Peninsula and a southern venture into the Sound.

On the flight back to base they scouted the feature known to them as the Neny Trough, later named the Neny Glacier and the Gibbs Glacier, which, with a trend of 140˚ true, appeared to lead easily down to Wilkins’s Mobiloil Inlet and provide a route to the East Coast. They then took a close look at the very steep and crevassed slopes of the glaciers which drained it north-westwards in the hope of finding a sledgeable route down to the sea-ice. Finally, they inspected the Northeast Glacier, which they correctly saw as a feasible, although difficult, sledging route to the plateau.

Black moved quickly, even in the depth of winter, to start exploring the hinterland and to find a way over the plateau. He also saw merit in setting up a weather station on the plateau from which to understand and forecast the weather. (Keith Holmes – “He actually wrote that a high-altitude field meteorological station had already been established before the first flight, but this was an error”.

On the ground, Bertrand recorded that; –

“During the winter, three short sledge journeys were made…. The first of these began on July 21 when Black, Ronne, Healy and Carroll set out on a scouting party up the lower slopes of [what they had by then named] Northeast Glacier, camping at the foot of the first steep icefall. At 10.00 the next morning it was light enough for Black and Ronne to proceed up the glacier to an elevation of 2184 feet, about 12 miles from East Base. A crevassed area of blue-green ice near the limit of their climb, and a 1000 feet icefall on the southeast side of the glacier, from which avalanches came crashing down every few minutes, made caution imperative, but the two men were convinced that by double teaming on the sledges, roping, and careful scouting, this route could be used to reach the peninsular upland. They re-joined Healy and Carroll and the party made a rapid descent to East Base.”

“On August 2 and 3, the same party, with one sledge and 15 dogs, made a second reconnaissance. This time it was to the southward, to investigate the possibilities of reaching the upland via one of the three glaciers that enter Neny Fjord. Ice cliffs prevented access to glaciers which had looked like possible routes on aerial photographs…. Each site was rejected. A successful route via Neny Fjord was used later…. but because of the short period of daylight, the party missed finding it on this trip. On August 3rd, it was concluded that Northeast Glacier offered the better route to the upland plateau.”

It was during a flight in September, that Ronne and Carroll spotted a possible “precarious side-hill route” which was first used, in October, by Dyer, Knowles and Eklund to get up into the Neny Glacier from the sea-ice. This was the route which the search party used in January to guide Ronne and Eklund safely home.

(Keith Holmes – “From personal experience and satellite images this is believed to have been the Snowshoe Glacier rather than the shorter, much steeper and heavily crevassed Neny Glacier“).

“The third winter sledge journey was an all-out effort to place a cache on the upland plateau…. On August 6, 1940, Black, Ronne, Healy, Dyer and Paul H. Knowles, with a supporting party of Carl R. Eklund, Hilton, Carroll, Lytton C. Musselman, and Harry Darlington III, set out with a total of 55 dogs in seven teams to ascend Northeast Glacier.”

After ten and a half miles, they camped, at 2,000 feet above sea level, but the next day they only covered only one and a quarter mile up the steep and crevassed slopes to 3,500 feet. This was the foot of what was later informally known as Sodabread. Strong winds then held them up, but they reached the plateau edge on August 9th and camped at 5,370 feet in 68˚ 08’ S, 66˚ 32’ W, having travelled about five and a half miles. Once again gale force winds returned, destroying one tent and creating havoc with their camp. When it ended on August 12th, they broke camp rather than explore further across the plateau, and returned to base the next day after a difficult return down the glacier.

The weather station, the first of its kind in Antarctica, was eventually established on October 29th at a commanding point some twelve miles east of the base at a height of 5,500 feet above sea level at 68˚ 07’S, 66˚ 30’W. A party of six men, Healy, Musselman, Darlington, Hilton, Lehrke and Palmer, had set out on October 20th with four dog teams carrying 1300 lbs of stores and equipment. They arrived at the site on the 25th, and Lehrke and Palmer made their first radio transmission on October 29th. Their last was on December 30th, 1940.

On September 12th and 20th, Knowles, Hilton and Darlington, supported by Healy and Musselmen, set out up the Northeast Glacier to cross the plateau and establish a depot of 2300 lbs at the head of the glacier later named Bills Gulch. (Keith Holmes – The position was determined as 68˚ 05’S, 65˚ 50’ W, which is probably five or six miles east of its actual location).

On September 27 Knowles, Hilton, Darlington and Musselman left on a second, and this time successful attempt to cross the Antarctic Peninsula, They visited but did not move the cache put down at the head of Bill’s Gulch. While descending Bill’s Gulch into Trail Inlet Knowles broke through a snow bridge and fell into a crevasse. “He went down fifteen feet then a bridge broke, but Darlington

and Musselman were roped to him and they were able to pull him up. While Darlington held the weight after digging in his heels and lying back on the line Musselman went up to the hole and helped Knowles up over the edge where the line had cut in. For some minutes Knowles had been looking into Eternity in the form of a hole which became too dark to see much below about three hundred feet”. This was the journey on which the lead dog Bill was killed, and the Glacier was named after him. The party continued on and travelled as far south as “Hilton Inlet”, before returning to East Base on Stonington, where they arrived on October 15. Their route is shown on the Dyer map and the schematic map below.

Knowles made his final local, and quite remarkable, journey with Dyer and Eklund, using a single dog team, between October 26th and 29th. On this occasion they travelled up the Northeast Glacier and:

“entered Neny Fjord by way of the low saddle east of Stonington Island overlooking the foot of Neny Glacier at the head of the fjord. Traversing the col, they travelled along the steep slope on the northeast side of the fjord until they were able to come down onto Neny Glacier.”

The next day they made slow progress and camped further up the glacier at a height of 1770 feet, and on the 28th they reached 2680 feet, where they left a small depot. They returned to base the following day, using a snow ramp off the Neny Glacier and on to the sea-ice. All three men had pioneered a dramatic escape route off the plateau which they thought each might have to use on their main journeys. It seems that only Bertrand has ever published these details, and not until 1971.

(Keith Holmes- “To my knowledge, the route has never been repeated, and I wonder whether the snow and ice conditions were exceptionally favourable this season for so many difficult routes to have been taken in such terribly broken country.”)

The names Armadillo, Fleming Glacier, Bill’s Gulch, Clarkson Point, Three Slice Nunatak, Mount Dudley, Billycock Hill were given.

In order to explore the area south and southwest of Alexander Island, and to delineate the coastline of the Pacific sector, Black had originally planned to fly a sledging party to the vicinity of Charcot Island, but, by the end of September, bad weather had prevented the pilots from setting up the necessary depots in George VI Sound and on Charcot Island.

Three major journeys were planned by Black after the Midwinter period:

- The West Coast Journey

- The Plateau Survey Journey

- The Weddell Coast Journey

Unable to establish the West Coast Party by air, Black despatched a party of seven men with five teams, each of eleven dogs, from East Base on November 6th, planning to achieve the objective overland. Finn Ronne was the group’s leader.

Paul Knowles and Don Hilton were to provide support to the West Coast Party as far as the Wordie Ice Shelf, and turn back within a week. Once the remaining five had gained the plateau and reached the Wordie Cache, Glenn Dyer, Lytten Musselman and Joseph Healy were to split off and explore and survey southeastwards towards the Eternity Range. After returning to Stonington, Paul Knowles, Don Hilton and Harry Darlington were to travel to the East Coast and south to 74˚ before turning north to Three Slice Nunatak and back over the Plateau to Stonington.

The West Coast Journey

The five teams made good progress past Windy Valley and Cape Berteaux and, after a few hours searching for an easy slope, gained access to the northern end of the Wordie Ice Shelf on November 10th. Ronne described the next four days of travel through the crevasses of the Wordie Ice Shelf as among the most dangerous in the Antarctic, but in good weather they made safe progress, and, on November 12th, Knowles and Hilton turned back for home, a few miles short of where the Wordie Cache had been laid on May 21st.

However, a winter storm had apparently blown down the flagstaff marker for the Wordie Cache, and despite a thorough search, Ronne and his men were unable to find it, and had to conclude that it had been buried under more than twelve feet of snow. To make matters worse, by mistake, the combined sledging parties (the West Coast and Plateau Survey Parties) had taken only one primus and one cooker, which made it even more necessary to fly in a new cache to the Wordie location as soon as possible – on such little things can such major plans fail.

The first opportunity to re-establish the Wordie Cache, allowing the parties to separate, was on November 16th, and at 1:06 a.m. Black, Snow (pilot), Perce, Sims and Sharbonneau took off with stoves, fuel and food and landed at 2:00 a.m. at 69 33 S , 66.55 W, establishing the ‘”new” Wordie Cache. Dr. Sims checked each member of the trail party, and Ronne and Dyer were each given sets of aerial photographs from a flight on November 12th, covering parts of both parties future plans.

As the men climbed slowly up to the plateau at 7,300 feet above sea level, they encountered poor visibility and deep heavy snow which reduced their daily haul to between four and eight miles. On November 21st, when the weather cleared, they recognised their position, from aerial photographs, as being at the top of a long and gentle glacier which was free from crevasses.

Here Ronne, the “West Coast Party”, released Dyer, Musselman and Healy (the “Plateau Survey Party”) to start their journey across the Plateau, southeast towards the Eternity Range.

(Keith Holmes – “It is not obvious from Ronne’s camp co-ordinates exactly where he was at this point because they place him among mountains low on the western flank of the peninsula. He described how the supporting party helped them descend the glacier to 5,100 feet, at which point they returned and Finn and Carl moved “quickly down the glacier to the valley running north and south”. It seems, however, that his campsites of November 20th and 21st were probably at a higher level”).

“Our intention was to stay at our present elevation of 5,000 feet and travel south, past the Seward Mountains, and then go westward”.

Up to December 3rd they had good surfaces and easy sledging “in the long valley with high mountains on both sides,” where they were able firmly to fix the position of mountains seen on aerial photographs.

Although Ronne had planned to stay high up on the plateau, and carried sufficient food to complete his planned journey, Black now instructed him to descend to KIng George VI Sound to collect the Batterbee Cache which had been established by air on November 12th, at 71˚ 45’ S, 67˚ 50’ W.

(Keith Holmes – “Ronne grumbled about this decision in his account, but it later turned out to be a major factor in his survival. As he and Eklund descended a long smooth glacier to the Sound they could see moraines extending out into it from the near shore.”)

On December 3rd, they easily found the Batterbee cache which had geographical co-ordinates that place it some miles south of the Batterbee Range, and by the next afternoon they had completed a photographic panorama and a round of angles. They then set off towards a “table-shaped stratified mountain” on the south-eastern side of Alexander Island. This seems to have been the feature later named Coal Nunatak, alongside which they camped after a good run of twenty-two miles. Just before it, they had run into a band of pressure ice four hundred yards wide which extended south-eastwards towards the horizon, and around the nunatak they found freshwater pools and saw snow petrels.

They then climbed up from the Sound to the foot of the Nunatak around the moraine and then sledged on land, rising up to 1600 feet. Such a route to the camp of December 6th makes the previous day’s longitude somewhat too far east. After sledging comfortably along the southern flank of Alexander Island they turned south and descended again to the Sound, crossing to its southern shore along which they started sledging, westwards, on December 10th.

After a lie-up on the 11th, Ronne and Eklund approached the “rock nunatak” which was named Eklund Island, and the following day they made camp nearby. Here, over three days, they fixed their position (the latitude was spot on, and the longitude no more than three miles out), measured the magnetic variation, observed snow petrels, and erected a stone cairn on the highest point, which Ronne believed to be about 1000 feet above sea level. In the cairn they placed a Claim Sheet issued by the State Department.

To the west, the ice was badly broken, and it took them two days to find a way through, but they made more than twenty-five miles on December 17th and came onto wavy sea-ice with its lower levels containing seawater. This must have been at or near the feature now known as DeAtley Island. Here they also saw gulls and petrels, and noted the tracks of penguins and seals. They continued north-westwards, making good mileage, apparently over sea-ice until they were stopped by a belt of seemingly impenetrable pressure ice on December 21st. They thus turned southward up a slope onto what seemed to be, in Black’s words, “a higher rim of ice-covered land” and continued westwards.

Black described how, at midnight on the 21st, Ronne spoke to him by radio from their camp “at 72˚ 32’ S, 76˚ 51.5’ W” from which they were looking northwards over open sea. Within four hours, Snow, Perce and Carroll set out towards them in the aircraft on a photographic reconnaissance. They intersected the coast about 30 miles east of Ronne’s camp, unheard by the men on the ground, flew over what became known as the Snow Nunataks, and continued westwards along the Antarctic coastline for an hour and a half.

Ronne and Eklund began their homeward return on January 22nd, heading across the sea-ice of what is now called the Ronne Entrance, and aiming for the southern coast of Alexander Island. They soon encountered large melt water pools which had frozen into vicious, glass-like fragments which severely cut the dogs feet. On December 30th, just east of Faure Inlet, they climbed up onto the slopes of the Island to get better surfaces at about 1000 feet above sea level, but the foot damage had been done, and would continue when they got back onto the similar surface of the Sound. On January 2nd, they appear to have camped near Titan Nunatak, a feature noted by Lincoln Ellsworth many years before, and the next day they reached the Sound, north of Corner Cliffs and Coal Nunatak. Although the dogs had suffered terribly, there had been no alternative but to press on. Ronne and Eklund tried to save the best dogs by carrying them on the sledges, but, in the end, they had to shoot five of the worst affected. They thus arrived at the Batterbee Cache on January 4th with only seven dogs. If the cache (which earlier “was of no value to us, except in case of an emergency”) had not been there, the two men would have been in desperate need of an aircraft rescue. But their radio transmitter had failed many days beforehand, and although they could hear the base, they couldn’t transmit.

By the evening of January 19th Ronne’s co-ordinates had him camped on the eastern side of the Sound below the Warren Ice Piedmont and at the foot of the Riley Glacier. The next day, “About twenty miles south of the Rymill Party’s route, we sighted a long and smooth glacier. We had only a few crevasses to cross in order to reach the high elevation leading to the Wordie Shelf ice cache.”

(Keith Holmes – His route at this point is unclear, but the coordinates of their camp on the 20th suggest they passed between Mounts Noel and Allen, and the camp the following day was well up on the plateau, within five miles of the Wordie Cache, which they found early on January 22nd).

On January 22nd and 23rd Ronne and Eklund made good progress down to, and across, the Wordie Ice Shelf.

The remainder of this story will be added upon receipt of the Journey Reports

The Plateau Survey Journey

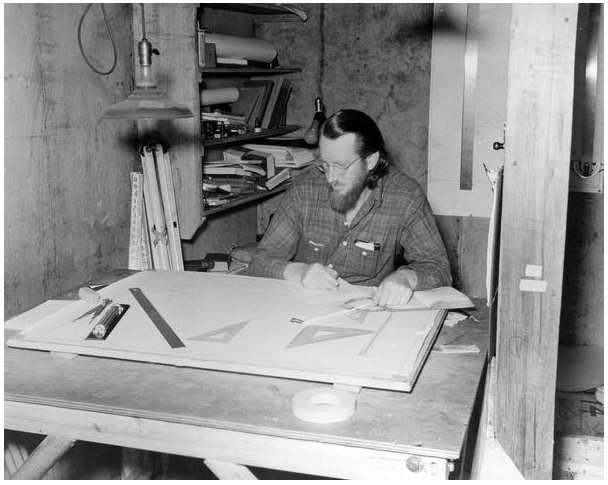

After leaving Ronne and Eklund on November 22nd, the Survey Party, comprising Glenn Dyer, Lytten Musselman and Joe Healy, with one eleven-dog team, reached what they called the Eternity Range on November 25th. From there they began extending ground control as far as 70˚ 53’S, 63˚ 38’ W, (the area subsequently named the Dyer Plateau) and collecting geological samples. They arrived back at East Base on December 12th, via the Wordie Cache.Using information in Dyer’s manuscript, Bertrand described in greater detail how the party had set off in a south-easterly direction from their campsite at 70˚ 16’S, 66˚ 59’W, with food for eighteen days. Moving around a high knoll they climbed up to 7150 feet and had a clear view of the terrain some twenty miles ahead of them, although cloud descended later in the day. On that first day, November 22nd, they camped after travelling 17.8 miles. They pushed on in cloud the next day at slightly lower elevation, and again on November 23rd. The following day was at last sunny and they were able to take survey readings and travel 19 miles. On the 25th they made another 19 miles, ending up camping in the lee of a small nunatak in strong wind which pinned them down the next day (and possibly the following also). On November 28th, they reached a small outlying peak of the northern end of a mountain range and placed a US Claim Sheet in a cairn at 70˚ 53’S, 63˚ 38’W.

The Dyer Survey Party returned to Stonington via the Plateau and probably “Sodabread” but this story will be finalized after review of “Americans in Antarctica” and Reports and Diaries held by John Dyer and www.usas1939.org.

The Weddell Coast Journey

Returning to East Base after supporting the East Coast Party, Knowles and Hilton were joined by Harry Darlington (at 19, the youngest member of the expedition). The three men then set out on November 19 for the Weddell Sea coast with two teams of 11 dogs each, and travelled South via the Northeast Glacier, Bill’s Gulch and the Larsen Ice Shelf, returning by the same route.

From this journey the many names of the USASE personnel were permanently recorded on the map above. Unfortunately, personal details about this journey, as well as details about the dogs, are not available. Scientific reports related that they travelled in a southerly direction to a latitude of 71° 57’S, to the feature they named Hilton Inlet, and were successful in collecting geological data and in determining the extension of the Weddell Sea shelf ice. Their journey lasted nearly a month, and although they met with some poor weather, for the most part the going was good. Due to the earlier pre-laid cache deposits, man and dog food was sufficient. Base leader Black noted that, upon their return, both men and dogs appeared to be in good shape, but only twenty of the twenty-two dogs came back. There was no mention of what happened to the two dogs.

In October, 1974, a BAS sledge party (comprising Surveyor Roger Scott and GA Graham Wright) found a note in a bottle left at Three Slice Nunatak by Knowles, Hilton and Darlington. It included a US Claim Form and details of a cache they had left nearby. The relevant Journey Report (E1974K12a) doesn’t mention the discovery, which was made in

The catalog of Scientific work carried out the the USASE at both East and West Bases is available below:

(Keith Holmes -“The topographic results of this work were incorporated into the 1943 issue of the United States “Sailing Directions for Antarctica” the chart of which, number 4562, was reviewed by Arthur Hinks of the Royal Geographical Society. He was very critical of the names and features assigned to the west coast of the Weddell Sea“.

An account of the Ronne and Eklund Journey published by Paul Gurling (Surveyor, Fossil Bluff – 1970 and Stonington -1971) in the Polar Record, 1979

Ashley Snow evacuated the base in two flights of the Condor aircraft to the Biscoe Islands, where the crew of the Bear had identified a landing strip on the snow dome of what they called Mikkelsen Island, and what is now formally known as Watkins Island.

(Keith Holmes – “The event is recorded in the US Sailing Directions (page 149) which labelled the location as Mikkelsen Island, and by Hattersley-Smith (page 596), who wrote that the aircraft was abandoned on the island which had by then been formally named as Watkins Island. At some stage, at least one website confusingly introduced the name Watson Island as the Condor’s final resting place”).

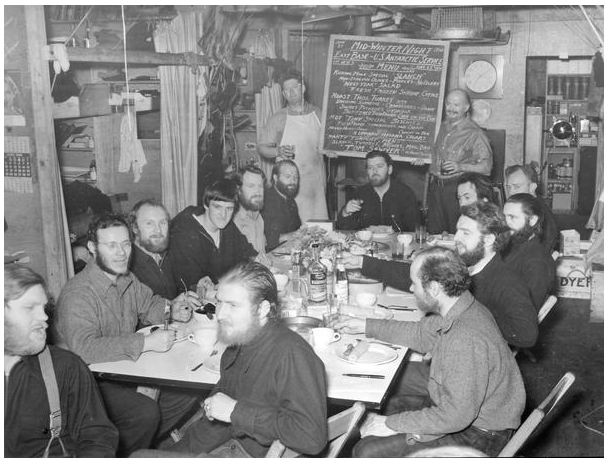

(For an interactive version of the USASE Group photo, go to www.usas1939.org)

Steve Wormald – Adelaide 1969, Stonington 1970 and 1973, Rothera 1974-1977