This is the story of our return to the Fossil Bluff base from fieldwork in June 1975

Bad light had precluded further accurate surveying and glaciological work. The sun had disappeared below the northern horizon and would not return, at our location, for two and a half months.

History of Fossil Bluff

The location for Fossil Bluff Base was first spotted in October 1936 by Bertram, Fleming, and Stephenson during their highly successful British Graham Land Expedition (Southern Lights Expedition and also on Stonington page) from 1934 to 1937. As they sledged down King George VI Sound for the first time in Antarctic exploration, they saw a tiny, narrow promontory which offered a moderate gradient on which a small base could be established. This promontory of ice-covered “moraine” was the only suitable location within hundreds of miles along the east coast of Alexander Island. There was also a smooth gentle slope leading up from the ice shelf of George VI Sound to the foot of the promontory. This would provide easy access to the firm ground for future sledging parties and logistics.

View from a few hundred metres above Fossil Bluff, shows the narrow promontory which Bertram found. The small, black square is the base.

Fossil Bluff is located on the east coast of Alexander Island approximately halfway down George VI Sound from the northern ice front. Its location is at 71deg 20min South and 68deg 17 min West.

Moving forward, in 1949, Sir Vivian Fuchs and Raymond Adie sledged the long journey down King George VI Sound. Sir Vivian noted the area for future exploration and, in 1961 instigated the establishment of the permanent Base (or field station) to be named Fossil Bluff.

In the same year, Fossil Bluff was first occupied and over-wintered by FIDS Cliff Pearce, John Smith and Brian Taylor. The hut was basically an empty box and these three gentlemen initially got to fitting out the interior (and notably the Rayburn coal burning stove!) something which future Bluff winterers have always appreciated!

View at ground level from the South towards Fossil Bluff, showing

the small promontory where the Base was established.

Fossil Bluff as a Hub for Glaciological Research

Fossil Bluff later became the hub for glaciological research over a geographical area of thousands of square kilometers. Wintering parties of four men occupied the hut all year as glaciology research, mapping and overland travel on the Sound was impossible in summer. This was due to rivers and lakes forming all across the ice surface from ice and snow melt run-off from the adjacent mountains of Alexander Island.

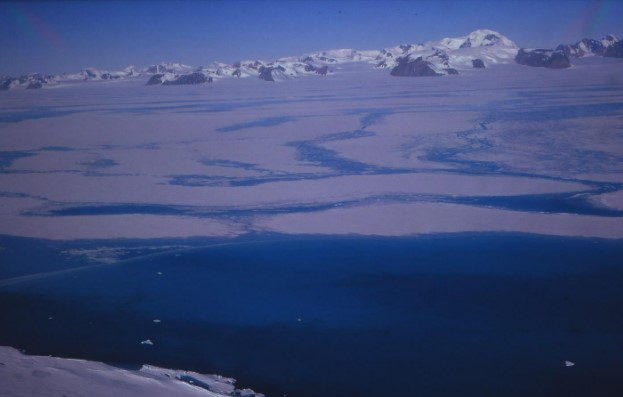

Rivers and lakes on George VI sound ice surface in the summer

The ‘Bluff’ is a one room hut measuring 19ft by 12ft (pre-metrics!) with an adjacent genny shed and sledging store. The single room has four bunk beds at one end, a coal burning Rayburn stove midway and a work bench at the other end. In the centre of the room is the dining table. This rather old and non-descript wooden four-seater table hosted many FIDS, over the summer seasons, in addition to the over wintering parties. These varied summer visits included BAS’s top brass, and up to thirteen FIDS crowded around that table in summer if grounded during poor flying weather. The old table often hosted the storied Twin Otter pilots of our era – Dave Rowley, Bert Conchie and Giles Kershaw. Fossil Bluff was the smallest BAS Base.

The Bluff hut taken from the front, just after stores were delivered

during the summer season.hoto 6: Fossil Bluff with Pyramid Mountain in the background

Lucky FIDS would come down for a few days break and R&R, during the summer season. They normally came from Adelaide Island Base and would do some weather reporting for the planes, and other odd jobs, in the thick of summer flying operations.

The eternally popular visiting cook, Big Mac, doing a few repairs before “conjuring up” some delicious scones!!

Only twenty-eight FIDS have over wintered at Fossil Bluff, of which just eleven spent two winters.

The story follows and covers the completion of field work, and then general life at BAS’s smallest Base during its last winter of occupancy over the 1975 – 76 winter period. The Base was finally closed for wintering operations in 1976. The FIDS overwintering this last year were Jonathan Walton, Graham Tourney, Peter Lennon, and Tim Stewart, and joined by our retired husky (Gerry Player). Gerry succeeded our dear old Rasmus. Rasmus was thought to be the oldest ex-sledge dog in Antarctica. Rasmus had sadly passed away in July 1974.

Completing field work before the sun disappears and Winter is upon us. As winter approaches, the sun seems to sink more quickly with each passing day, until the day it hardly rises above the northern horizon before sliding down out of sight again. We would lose 30-45 minutes of useful light as each day passed each day from undertaking or our precise surveying measurements. The sun finally disappeared in early May.

“Shadows grow so long before my eyes” (with acknowledgments to

Peter Frampton)

The winter sun just making it above the horizon in late April 1975

In late May we just managed to complete our survey network across the George VI Sound, as light faded. Two of us then headed for Spartan Cwm, another field station for final checks before winter darkness. Then on to the Bluff for winter hibernation. The sun would not rise above the horizon again for two and a half months.

Back on Base

The Bluff had been empty for over two months whilst we completed our Autumn field work as our bigger projects required all four of us (plus the dog!). So, on arriving back at the Bluff, the hut would be a big cold box at around minus 34 degrees C, about twice as cold as the inside of a domestic freezer unit. We quickly set about getting the coal burning Rayburn fired up, organising the hut inside, drilling for water, and breaking out and storing all our field equipment.

Gash Duties

The four of us overwintering did not include for a Cook, Doctor, Radio Operator or Met. man. We were ‘it’. The dog did nothing (but could be blamed for everything) !!

Enjoying a nutty block on the steps of Fossil Bluff. He slept outside

all through the Winter

Initially, we set up a routine for gash duties for periods of two full days each. During these two day stints the Gash Man was responsible for everything concerning the day to day running of the Base. Maybe the best part of this schedule is that one was not responsible for any of these activities during one’s 6 days off, and was free to do whatever. Of course, there was a bit of mixing and helping, but this was voluntary.

The gash man’s day would always begin with re-vitalizing the coal fire in the Rayburn stove. The previous evening the fire in the Rayburn would be backed-up enough such that it would not choke out if there was no wind, but also that it would not burn itself out during a blow (high wind). This could be a tricky estimate depending on the strength of the wind speed. A strong wind rising in the night and flowing across the chimney would draw the fire and it would burn hotter and may burn itself out.

During July 1975 the early morning temperature inside the hut was minus fifteen degC as there was no wall or roof insultation to speak of. It was a terrible crime if the previous gash man had “let” the fire go out overnight before the next gash man took over in the morning. This would represent a serious loss of status for that preceding gash man! Well, nothing to do but blame the dog!

Whilst all gash jobs were important, cooking was the priority. Cooking for the Gash man meant initially going to the ‘shops’ for food and water. There was no room inside the hut to store food, so it was all stored outside in the wooden freight boxes used to transport it South. The boxes were set out in rows at the rear of the hut. We made a map of the rows and lines of boxes and their contents.

Gash man Jonathan serving his Articles before becoming President

of the Antarctic Club 49 years later! (Note the primus roaring away on top of

the Rayburn, and the washing machine (pan) to the right of the kettle)

In summer, it was easy to wander out and pick up the desired supplies. But in Winter, when it was black as a hat, and maybe with a small-time blizzard blasting through, it was a different matter. Running out with Tilley lamp in one hand and ice axe in the other to search the snowed -up food lines was much slower, and more challenging. The rows of the food boxes had marker poles at each end and the deal was to memorize the map in the hut, say row 4 and 6 boxes along for baked beans, then make a dash for it, pace out 6 boxes along,

dig feverishly into the drift and pull out the goods. Oh – it’s a tin of Bird’s Custard powder – try one more box along… Incidentally, we kept an extra year’s supply of the basics in the event that the ship was unable to relieve the Peninsula Bases during the next summer should it be in a very bad sea ice year.

The food store stacked up behind the hut (summer shot before

organising and mapping). The Scottish flag flying high!

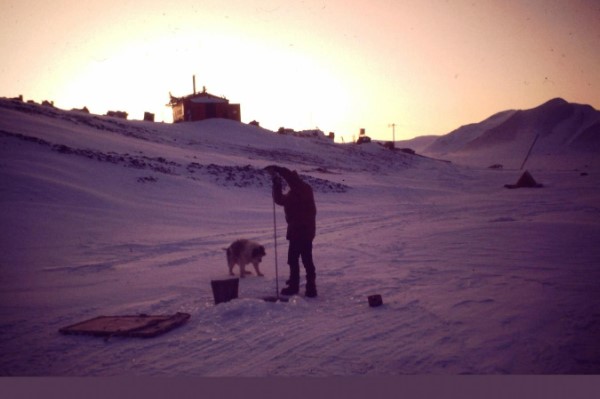

There was a permanent ice-covered lake at the foot of the hut slope, about 25 to 30 metres from the hut. For our water supply we chopped a square about a 50cm sq. and 20 to 30 cm deep “basin” out of the lake surface ice. We would drill down through the ice in the middle of this basin to the water below. When the water was reached it would bubble up into the square basin. We could then slap a couple of buckets into this little reservoir and head off back to the hut to fill the galvanized dustbin, our in-house supply.

As the winter progressed the lake ice would become thicker so that eventually we would have to drill through 2 metres thickness of ice to reach the lake water. As we neared the water level we didn’t know exactly when we would break through the ice, and great care was needed near the end because if we burst through the bottom of the ice with the cold steel drill (at around minus 30 degC), the drill bit would freeze up instantly as it entered the water. Then it would be a big job for the gash man to free the frozen-in drill. So, it was

important to go very gently on approaching the water layer and to pull up super-fast on reaching the water. Of course, this was all done in darkness and the weather conditions of the day.

We would do two or three trips to the well to fill two buckets each time in order to fill up the dustbin in the hut . A water run would be done every 2 or 3 days. On filling the buckets, the next challenge was that the slope back up to the hut, in winter and darkness, was covered in a thin layer of snow and it was just a little too steep to walk up (and not slide back down) carrying a couple of buckets of water. A bit of momentum – a run up the slope – was necessary to cover this short uphill section. Then the water would slop around and spill out

of the buckets, often down one’s trousers. By the time we reached the hut steps the buckets were often just two thirds full, but still ok!

The square hole we chipped out of the surface ice, having filled with water, would then freeze hard and a new squared-off hole (basin) and fresh drilling would be required for the next water run. We often mused in that mid-run up the slope with the sloshing buckets, that Palmer Station, which we had helped relieve on our way South, had their own desalination plant – with running water in the Base!

Drilling for water at the Bluff

Most days we would set up a mid- morning smoko (i.e. tea- break in FIDS language) making fresh baps, scones and maybe cakes. This would be a good break, especially for Tim who would mostly be working for many hours on the Muskegs ( Kegs) tractors or skidoos in the freezing garage.

Every couple of days the Gash man would bake bread. This was technical as he needed to bring the Rayburn oven to the correct and constant temperature for 45 minutes, or so. The amount of coal required to build the fire for the constant heat period would often require a run outside to assess the wind speed. A strong wind drawing the hot air out of the Rayburn chimney could have a real effect on the temperature of the oven – and the outcome of the

bake.

The Gash man would decide on the evening meal, then prepare, cook and do the washing up. Most meals and menus came from a FID-designed cook book, plus a bit of our own experimentation. Nearly all meals were prepared on a couple of primus stoves which sat on the top of Rayburn.

Besides cleaning up the plates, pans, surfaces and generally around the hut the Gash man would bring in a couple of bags of coal for the Rayburn (which had written on the bag “Specially packed for British Antarctic Survey’). After all that, he was free to relax for the rest of the evening!

Outside the Hut

Outside the conditions would be completely dark, unless the clouds allowed a glimmer of orange/pink in the northern sky for up to an hour around midday.

Weak glimmer in the northern sky for up to an hour around midday

What would the three other Fids not on gash duties do? As mentioned earlier, there were 6 free days between gash duties. There were lots of jobs to get on with. One entry in the Base diary from the infamous Malky Macrae quoted, on one occasion, “Today, I carried a box outside”. Usually though, we were not so busy!

Generally, we would occupy ourselves with:-

writing up field project data and reports,

duplicating field data and measurements,

servicing the skidoos, Kegs, sledges, and tents

planning for next season’s Projects

repairing and improving travel equipment or outdoor clothing, and

reading.

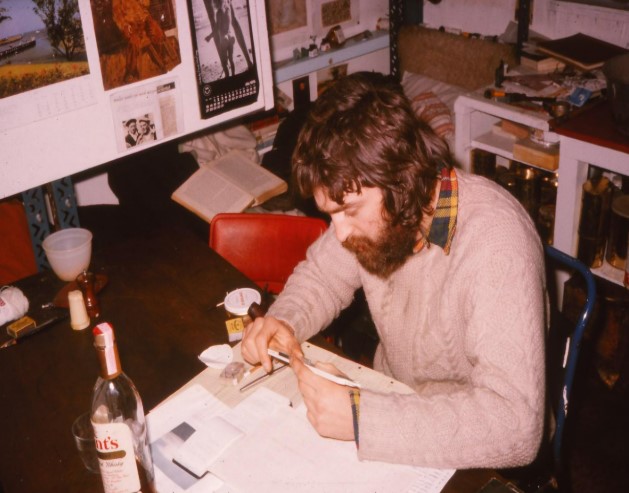

Peter Lennon working up some field observations. Note the “Slide Rule”!

One extra task we took up was re-painting of the inside of the hut. This was long overdue after many years of cooking with the Rayburn and primuses. It was a fiddly job as all the walls were lined with shelves and full of tins and other stuff. But we got the task done over a couple of weeks. The difference can be seen between the photo of gash man cooking and that of sledge building. Interestingly, the fresh paint on the wall down by the side of my bottom bunk stayed wet for four months in the cool temperatures near the floor.

Outside, as the weeks progressed, the glow in the northern sky

brightened during the mid-day period.

Midwinter comes around

Midwinter is the marker for reaching halfway through the dark period. (“It’s all downhill from here!”). It offered a nice break and party time (though partying is stretching it a bit when there are just four of you!). We looked forward to Midwinter for a bit of dressing up, party food and a wee dram. Our alcohol ration was taken from Royal Navy standards. I think it was 4 bottles of spirits per year and so many cans of beer. Stored outside, the latter froze and burst the cans, so didn’t count.

The great thing for the Bluffers was that we were delivered the same size turkey as every other Base. Back at the turkey suppliers in the UK, they had no idea that there were just 4 of us at the Bluff! So, we got the full- size job, like the other bases! We had to ram the turkey into the small Rayburn oven using a tent peg hammer to get it in!

Before our trip, whilst attending Scott Polar Research in Cambridge, a former Bluffer, Ian Rose, recounted a story to us of Rasmus nicking the turkey and hiding in an ice cave.

On midwinter’s morning he was spotted meandering his way back up the slope to the hut, with said turkey in his mouth. Unmarked and otherwise untouched, they grabbed it back from him and offered the old boy a big thank you! We were never quite sure if it was true, but it was a good story!

Mid Winter 1975. Small Base… BIG Turkey!

After Midwinter’s longest night (around 21 or 22 June) it became noticeably

lighter in the northern sky for that hour or so around our midday

Continuing Internal Jobs

Graham Tourney constructing a new sledge

As each day passed it became increasingly lighter in the northern sky and it was time to start focusing and preparing for next season’s projects. A new sledge was made up to carry the ice core samples that would be drilled and stored during our summer traverse across the Plateau. (These ice cores were subsequently sent to Denmark for detailed Isotope analysis to determine the temperature at deposition of the (snow), at the time of its deposition, from the deeper drilled cores this being from many hundreds of year’s earlier).

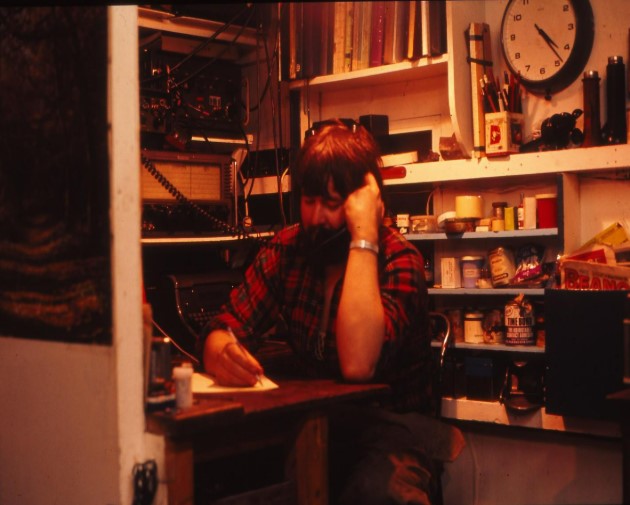

Radio Schedules

We kept up a daily radio ‘sched’ with Adelaide Island Base. This was a safety check, as well as once a month we would receive a 50 or 100 word long message from family or girlfriends. These were read out in public, as was the standard practice for the field guys during the summer sledging season. (This was all well before the Internet, PC’s, laptops, mobile phones were invented!)

Weather reporting was always on the menu and I remember (to the word) the weather report on one occasion, from Mike Harris, the Adelaide Radio Operator. He described, “Next week, the weather will be changeable, with a tendency to remain the same”. It may have sounded a bit gobbledygook but was clearly understood! Another time we had a FID’s sister’s message being relayed (through Mike) to say that that she had been learning to play golf and “had been slashing all over the green”. It took him a couple of goes to get that

one out!

“Next week the weather will be changeable with a tendency to

remain the same” (Jonathan on the radio sched.)

Winds

The late winter period produced more frequent winds, from the North. These strong late inter “blows” would lift the small chunks of mudstone off the adjacent mountain and batter them against the side and roof of the hut. They sounded like rifle shots. After some experience we could reasonably judge the windspeed from inside the hut, based on the noise and clatter of stone fragments hitting the hut. There followed unintentional consequences…

The Bog Tent

The winter blows would often be in the range of 40 to 70 knots and last for four to seven days. Nature meantime takes its toll and the urge to “spend a penny” would eventually win over the desire of waiting for calmer weather. One would try to “to wait it out” each time, but would never outlast the storm. So, a trip to the Bog tent would become inevitable.

The Bog tent was an old orange pyramid field tent equipped with a 15 gallon drum and a bog seat sat on the top. The dog was not allowed in the Bog tent, though to him this cosy tent, out of the wind, was (to him) was also the equivalent of the deli at Harrod’s!

The Bog tent was situated about 30 meters from the Hut. The trudge to it could not be taken lightly in a blow or blizzard, and a full outdoor dressing up would be warranted. I remember having to crawl, on several occasions, in strong winds, across the 30 meters to the tent as the spin drift and mudstone missiles pummeled my back. Of course, it was pitch black too.

On one occasion I reached the Bog tent in high winds, noise, and with the tent flapping crazily. As I entered the tent’s tunnel entrance, Rasmus became aware of me and made a late bolt for the door. I was pinned topside of the tunnel entrance whilst he took the low road, and we log-jammed. We were stuck for what seemed an age, but probably was no more than ten seconds,before his frantic four-legged scrabble ejected him out and I fell in onto the tent floor. The only thing to do then was to bare the bones of my arse on the

coldest bog seat in the Southern Hemisphere.

The jobs continued. It was time to check over and fix up the torn and rotting outdoor gear, along with servicing the Tilley lamps and primuses.

Look at those fingers go…

The sledge was finished and the inside of the hut looking much

brighter after the paint job. Once more the kitchen table reigns supremely

practical

Late Winter

As the window of light in the northern sky began to extend around the midday period, I would take a daily ski walk. It was of utmost importance to ski safely as an awkward fall could cause a twisted ankle or even break a leg. This would create undue and an unwelcome dependency and stress on one’s hut mates for months, as there is no chance of an air rescue in the dark winter conditions for several months.

However, with the Sun working its way back up to the horizon we were often blessed with the most beautiful skies, for an hour or so. I captured some of these on my ski-walks. This was to be the last winter for over-wintering personnel at the Bluff. These photos, therefore, are most likely, the last shots ever to be taken of late winter skies over Fossil Bluff .

Late July 1975. The sun is still below the horizon between one to

five degrees and picking out nacreous clouds (formed of ice crystals) which

form at 20 to 30km elevation up in the atmosphere. Spin drift showing at

ground level

Late winter at our isolated outpost.

Sunrise and sunset skies would be dramatic given suitable cloud

formations. The Bog tent showing up in glorious silhouette in this photo!!

As the late winter days passed, the skies turned to a pinky/ purple

glow over the mid-day period. (Taken without camera filters). The return of

the sun could not be far away

On 6 th August 1975 the sun returned, just filling the corner of South

Succession Cliffs and George VI Sound, before quickly sinking away again

After 2 ½ months of darkness, there was something deeply reassuring about the sun’s return.

The Sun Returns

After the return of the sun it quickly lifts into the sky each day opposite to the period of it sinking below the horizon. We prepare for the first field trip, but a little stretching of the legs was in order during preparations…

Young chap spent an hour waxing the bottoms of his skis. Maybe

time would have been better spent waxing the back of his anorak?

Jonathan and Gerry Player take a stroll

During the dark flat winter period we missed seeing the sparkling of

sunlight reflecting off the snow

Full light has returned and it’s time to get started on our first Project for the late winter/new spring season, August 1976.

Early Spring is the coldest period. It is minus 40degC as we are

loading up ready for our annual project work at Horse Point

Our last Winter at Fossil Bluff is over

I would like to acknowledge my fellow FID and Glaciologist, Jonathan Walton for photos 8,9,10,11,12

and my fellow FID and GA/ Mechanic Rog Tindley for photo 13.

All other photos taken by the Author, F. G Tourney (Fossil Bluff 1973-76)