Footsteps in the Snow – to Antarctica and Beyond

This experience led me to take a rock climbing course in the Cuillins of Skye the following year and I joined up with clubs such as the Edinburgh Mountaineering Club and The Junior Mountaineering Club of Scotland (JMCS) and eventually with the Scottish Mountaineering Club (SMC) itself. My main passion was for winter climbing, either up the gullies and ridges, or just a hike over the tops, and perhaps it was making those footsteps through the snow and ice that always gave me the feeling you were breaking new ground. It was about this time in the mid / late 60s that I became aware of BAS as ex-Fid John Winham (Met., Hope Bay 1960 & ’61) joined us in the JMCS. He was a great storyteller and kept us rapt for ages in the pubs and long car trips. And another ex-Fid joined us briefly a little time later, Jim Westwood (Geophysicist, Halley, 1963 & ’64). Another fine fellow but lacked the dog stories.

In 1968, SMC member Graham Tiso, and the only mountain equipment outfitter and retailer in the area at the time, asked four of us to join him on a climbing expedition to the Stauning Alps in eastern Greenland. For me the experience there was a real game changer. I was fascinated by the glaciers, and the ice cap which we could see in the distance from atop the mountain peaks, and even the clear Arctic scenery, air and lighting. Bringing the experience home with me I now saw the Highlands in different light. Everywhere around I could now see the lateral and terminal moraines and drumlins and could imagine the glaciers of an era ago filling the corries and valleys shaping the landscape.

At that time I was working in a laboratory for the Medical Research Council in Edinburgh while studying for an HNC in chemistry which I would gain the following year. Since I spent all my weekends and holidays climbing it was becoming more difficult to reconcile the two and I was beginning to regret the choice of chemistry as a career, something like geology would have been more appropriate, but chemistry was about the only subject I had any aptitude for. Meanwhile, Alistair “Bugs” McKeith went South as GA to Adelaide for 1968. I didn’t know him that well; as a climber he was in a totally different league but like many climbers we gathered in the pub of a night during the week. I’m not even sure what inspired him to go south except as member of the elite Edinburgh climbing group, “The Squirrels” he would have known of the climbing exploits of the rival Glaswegian group, “Creagh Dhu” at various bases in previous years. While down south he sent home Super 8 mm movies of his exploits and his folks would invite us over for a screening.

As soon as my exams were over I applied to BAS. I don’t remember much about the interview. I don’t even remember anything of the trip down. I don’t recall staying anywhere so I assume I made the round trip from home in a 24 hour period give or take but I do remember London as a humid, sticky and smelly place. It’s possible there was someone else with Bill Sloman but I only remember him. Nor do I remember any of his questions but I don’t remember it as an unpleasant experience so it must have been OK. I seem to remember going off for a medical also. Perhaps it was at the time of the interview or perhaps it was sometime later that I knew that I was being considered for a position at Signy Island. Although I was happy to be considered for a position at all I was a bit disappointed in not being assigned to a sledging base and I assumed that my lab experience was being considered more of an asset than my outdoor experience. However, even by the time of the Cambridge briefing, HQ had realized their error and had assigned me to Stonington and I quickly made buddies with others heading for the southern peninsula bases like Jim Woodhouse, Neil MacAllister and Dick Scoffom.

On the voyage south three young husky dogs, Kernek, Konga & Kovik, were also shipped down and joined us on the Biscoe when at Stanley to improve the gene pool in the breeding program at the sledging bases. I volunteered to look after them. Konga was the typical loveable husky but Kovik ( a half brother of Kernek) looked half wolf and was just as lurky as one and later proved to be quite a handful. During the journey south it was decided that a GA was needed at Fossil Bluff for the winter to aid in the glaciology program there. It’s hard to recall details 50 years later so I am not sure whether this was an oversight or a change of plan. I also think HQ had suggested or volunteered Neil for the position, something he was not overly happy about so he approached me to see if I would like to go instead. I wasn’t particularly enthusiastic about it either as I had been looking after the new dogs and was looking forward to the next two years dog sledging. Still, it was an opportunity to experience different activities and different modes of travel and I would still be promised a dog team at Stonington for my second year. With some misgivings I agreed to toss for it and but for the face of the queen I was on my way to the Bluff.

It was an interesting year and was spent with the Officer-in-Charge and glaciologist, George Kistruck, in his 2nd year, Malky Macrae, tractor mechanic also in his 2nd year from Halley Bay, and Paul Gurling, surveyor. We had several trips in the fall and spring doing glaciological work in the Sound and in a nearby glacier, and laid depots for the northern sledging parties for their upcoming season. But, being further south and darker than the northern bases, the winter was long with not that much to do. While on base we were required to take regular weather observations, code them up and transmit them. The little radio shack/met office walls were covered in copious useful hints from meteorologist, Kenn Back on a previous visit. Bedtime reading was George’s two volumes of Quaternary Geology. The grass is always greener on the other side, and somewhat naively, I was a becoming a little envious of the wide ranging dog sledging parties from Adelaide and Stonington. It was some years later before I recognized the value of my experience particularly in the fields of glaciology and meteorology at the Bluff, and that proved to be of much more worth than another thousand sledge miles.

I joined the dog teams in early November working (and training) with Steve Wormald, GA. and Ali Skinner, Geol., eventually taking over Steve’s team, The Admirals, on his departure home. I was loving every minute of it and in fall requested BAS for a third year at Stonners since I had ‘missed out’ on my first. I eventually got quite a terse reply saying that it was BAS policy, except in most unusual circumstances, that I must come out at the end of the 2nd year before being considered for a 3rd and that BAS dictates who should go where and not the other way round. Fine, and it was a great last year geologising with Nick Culshaw in the Arrowsmith Peninsula in the fall and with Bob (Rocky) Wyeth in the spring and summer. The summer work took us into uncharted territory, just a few dashed lines on the topo map. Plane table mapping in such an area was a very rewarding experience. We were back at base by the end of January ’72 with me packing for the voyage home.

Both the Biscoe and the Bransfield came down for the relief with Bill Sloman onboard. When we met he addressed me by first name. The last time we met was 2 ½ years go so either he had a really good memory or had done his homework and either impressed me. I was called into the BC’s office and I cannot recall who it was I met with, either Bill or Phil Wainwright, BC., but the message was clear; if I still wanted it I could have a 3rd year, and someone else would go home. Wow! What a gobsmacker! If I had been asked even just a few weeks ago I would have jumped at it. But now, having resigned to the fact that I would be going home I was now kind of looking forward to it, and then there were my folks. I knew from their letters just how much they were looking forward to my homecoming and how they were planning for it just a few weeks away. I just couldn’t disappointment them. From my later understanding the guy who was not now going home was read the riot act and, in fact, appears to have had quite a successful 2nd year.

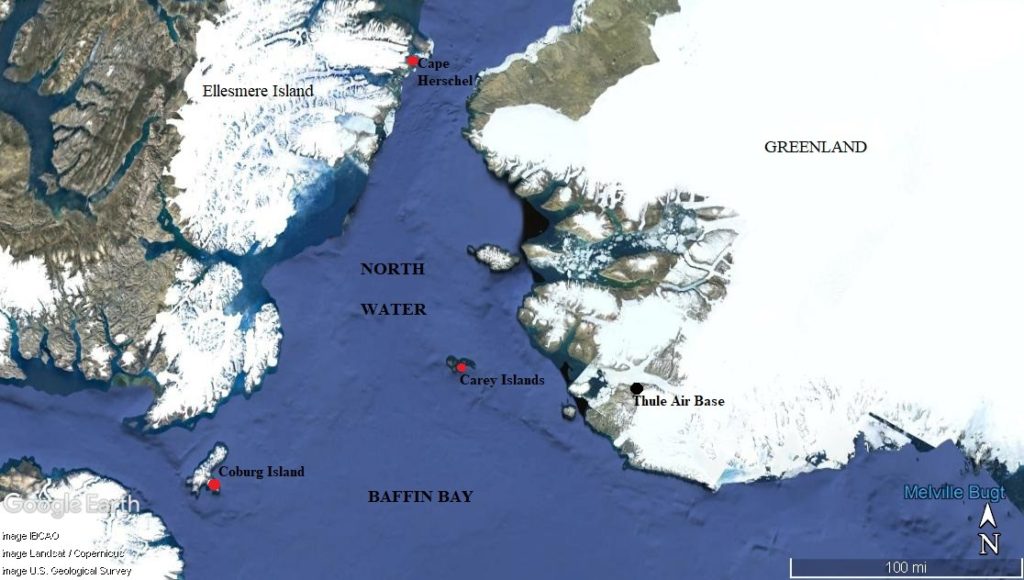

Now at home I had to decide what to do next. To have stayed down south for a 3rd year was one thing but I wasn’t sure I wanted to go down again. There was no question I loved what I was doing but it was how to make a career out of it and I’m not sure that repetitive trips with BAS would do that. So I went to Canada. In fact, I had my immigration papers issued when I found out about the Baffin Bay North Water Project, a glacio-climate study coordinated by The Arctic Institute of North America (AINA) with participation from McGill University, Montreal, and the technical university, ETH, Zurich, under the leadership of glaciologist Fritz Müller. Two small manned bases had already been set up in the first year, one on the Carey Is., off Greenland and one on Coburg Is., just south of Ellesmere Island. At least two ex-Fids had already been involved in the first year of the bases, Kenn Back and Phil Wainwright whom I knew, and Norris Riley (G.A. Halley Bay 1968-69)while Ralph Lenton, (ex-TAE, ex-Fid Signy, Admiralty Bay, Deception, Port Lockroy, Faraday, 1948-54) was logistics officer with AINA. Ex-Fids were everywhere and I recall bumping into Alan Weardon in Resolute a couple of times.

As it turned out, Phil & Kenn had had an unfortunate and pretty rough time of it. Funding was yet to come through so they were trying to set things up with a limited budget and little materials for the things they were supposed to do, and even worse, no wages. They left, dispirited. Fortunately, by the time I joined things were looking up. Fritz had quite a reputation as a scrounger, for aircraft hours and everything else. Only later, did I find out that much of our canned and dry foods had come from the beyond date scrap food pile at the U.S. Forces Base at not so far way Thule, Greenland. One of our guys had sent a letter to one of the manufactures of dehydrated pork cutlets complaining that they tasted a bit off only to be told by the manufactures that they were not surprised as they had stopped making them years ago. So, in the eyes of some, food evidently not suitable for the typical grunt was still good enough for us.

Anyhow, I joined in 1973 in the 2nd year of operation, setting up a 3rd base at Cape Herschel, Ellesmere Island and working with a glaciologist set up an array of glacio-poles and strain-rosettes on the sea ice across Smith Sound towards Greenland doing almost identical work I had done with George a couple of years earlier except with a bit more modern equipment. We even did a jolly over to Greenland but never told anyone about it as we didn’t go through customs. Along with regular weather reporting we also set up automatic recording weather stations. I wintered on Coburg Island where we also launched radio-sonde balloons for upper air soundings and also did regular sea ice thickness measurements. A RCAF Hercules even gave us a parachute drop at Xmas in complete darkness and at height because of the surrounding mountains, and it was spot on. In summer we also had a short stay at the McGill field research station on Axel Heiberg Island doing glacier measurements including drilling through the glacier using a recently developed hot water thermal drill.

The project came to an end in fall 1974. It was a great time, similar to Fids in many aspects (and sorry for Kenn and Phil’s darker days), with many new experiences, skills and techniques. It was with a great bunch of people, too, with personnel including women from six different nations all with similar interests, and some of whom I am still in contact with today. The climate was much more amenable than the Antarctic but one still had to maintain one’s guard as some of the storms were every bit as vicious as down south. Since little of the work was on glaciers we did not have crevasses to worry about, but much of the work was on sea ice which had its own dangers and we had no wish to emulate even part of Capt. Tyson’s 1,600 mile drift on an ice floe from these shores to off Labrador in 1872/73. We had many beautiful days and I recall one in particular when I had to get back to base from a camp several miles away. The trip involved part Skidoo and then part ski to traverse the slopes above a narrow but by then open water channel through the rugged coastline. It was absolutely gorgeous in the warm sun with the bright blue waters below, baby blue skies above, and surrounded by snow covered hill and peaks. I stopped for a smoke and to admire the scenery thinking how lucky I was and that I actually got paid to do this. Not very much, mind, 250 bucks a month after coercing Fritz to give me a bit more, for which I don’t think he actually ever forgave me. In contrast, the Twotter pilots were getting that every few days.

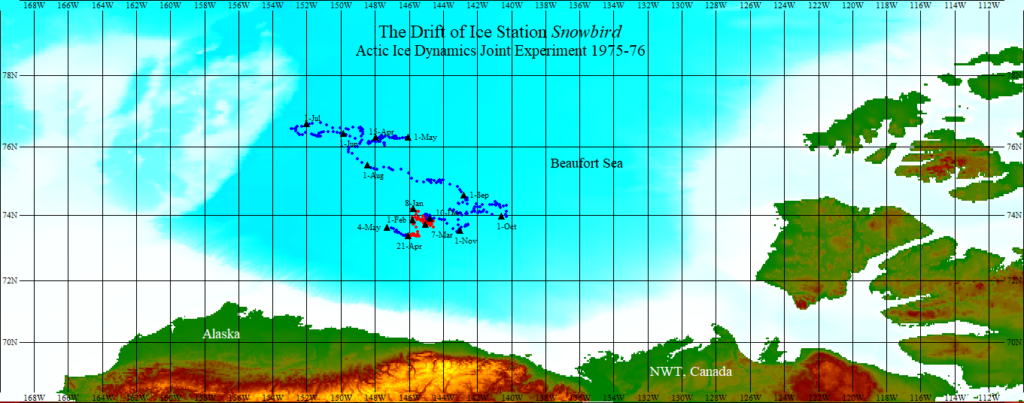

At the end of the project we were picked up by the new and currently still operational icebreaker Louis St. Laurent. We did some oceanographic stations on the way south. It was my first exposure to oceanography and Nansen Bottles and for my next project I was hired by McGill University as an oceanographic technician in 1975 and sent packing to Snowbird, an ice island in the middle of the Beaufort Sea. The Arctic Ice Dynamics Joint Experiment (AIDJEX), managed principally by the University of Washington, was in its main phase with one large camp and three satellite stations, of which Snowbird was one, on the sea ice to study how the ice moved and changed in response to weather and ocean. Enter another ex-Fid, Alan Gill, ex Admiralty and Hope Bay, 1958-59, and, of course, with Wally Herbert and others ex-Trans-Arctic Expedition, 1968-69. Alan had already been in the earlier pilot experiment and his experience and stoic personality were welcomed by many as the camps experienced upheaval in the splitting of the ice floes.

Two parts of Snowbird ended up three miles apart. He and I were part of the five man team on Snowbird and became good friends even joining up again later in Calgary for further adventures. As a further aside, I just missed one of Alan’s other companions on the Trans-Arctic Expedition and ex-Fid. Roy “Fritz” Koerner was then working for the Canadian Polar Continental Shelf Project (which also provided logistical support for the North Water Project) and during the field season he and his team where studying the ice caps of the Arctic Islands and one day Skidooed into our Cape Herschel station. They were greeted by the couple of guys left on base but unfortunately at the time myself and companion glaciologist were off doing our own field work.

AIDJEX ended in 1976 and I joined Dick Scoffam for a while on his farm near Edmonton. While with the North Water Project I was surprised to hear his voice passing traffic on one of the radio frequencies. At that time he was a radio operator for Panarctic Oils during their years of oil and gas exploration in the western Canadian Arctic; boom years for science and engineering in the Arctic. He was familiar with several of the consultant companies providing services for Panarctic and following one of his leads I then found myself working for Innovative Ventures Ltd. (IVL) in Calgary owned by Dr. Ron Goodman, previously of the federal department of Glaciology. As it turned out IVL was a blind company of the seismic company Phoenix Ventures Ltd, and as I have just found out, I just missed Steve Wormald by about a year as he was previously employed by them. The owner of Phoenix Ventures was Siegfried Bucher who did much of his earlier work in the Arctic by dog sledge.

I spent the next eight years with IVL or its affiliates with continual field trips ranging from oceanographic work in Davis Strait in the east to the coast of the Beaufort Sea on the west, and sea ice measurements and weather station installations throughout. One of my primary duties was as an “ice checker” utilizing a towed impulse radar sled to reconnoitre a safe route over thesea ice for the heavy Panarctic construction vehicles or the seismic convoys. On one of my trips with Dome Petroleum in the Beaufort I met ex-Fid, Jim Steen, (GA, Stonners, 1964-65). However, working in the “oil patch” was in sharp contrast to BAS or other projects I had worked on. Gone were the days of “I actually get paid to do this”. While the oil patch workers were no doubt experts in their own jobs few, if any, had any interest in where they were. In fact, most had no idea where they were, they could just as easily have been in the middle of the jungle, all they knew was they were on Rig or Camp such and such. There were good times, for sure, but much of it was ‘rush & wait”. No sooner would I be back from one trip when there would be a phone call to be on the next plane with scarcely enough time to do the laundry. Then I would sit for days at a time in the main base at Rae Point because they were actually not quite ready for you. Bored to death, having read all my books and seen all the movies, all I could think of was “They don’t pay me enough for all this shit”, and the only solace was to think about the wages building up in the pay cheque. Not that we were paid that much, and it was only after my bosses introduced a field allowance that I could see much difference.

There were a few older generation ex-Fids in the Calgary area. There was an attempt to get everyone together once in a while but I remember only one such event, at Ken Pawson’s (Port Lockroy, Admiralty Bay, 1948-40) home, and that would have been around 1977 or so. Alan Gill joined in for one or two field jobs with IVL about that time. I can’t remember now all the course of events at that time but he & Wally Herbert were also preparing for their circumnavigation of Greenland expedition by sledge and umiak. They had also been looking for a 3rd man and Alan, at some point, had suggested me. But, there had been another fellow on AIDJEX, whose name I can no longer remember, who had met up with Wally at some stage and Wally was super impressed with him. Alan also asked if I would like to take the dog teams over the Greenland plateau from east to west in preparation for their departure. That was another heck of a decision. It was something I dreamed of years ago, but now I had new home, a relatively new wife, a brand new son, and for the first time in many years, a regular salary, and in addition, my wife was never in the best of health and already found my absences on field trips quite demanding. It was hard to contemplate a long absence with no income so the answer had to be no. As it was, the Greenland venture was unsuccessful in its goal. The burly third man turned out not to be the ideal companion that Wally had anticipated and indeed may have contributed to the expedition’s premature conclusion.

Recession hit Canada in the early 1980s and the 20 year golden era of scientific exploration in the Artic dwindled as too did the oil & gas exploration. Companies closed their doors and I was out of a job. I did some field work for the company, Geotech, which under its remarkable leadership, had led the way in Arctic ice engineering. They had no permanent positions available but promised me as much field work as was possible. Then, one day I noticed an ad for a new ice testing facility in St. John’s, Newfoundland, for the National Research Council of Canada (NRC). They wanted Naval Architects and PhDs with a knowledge of ice so I was prepared to ignore it. “Go for it”, my wife said, “You never know where it might lead”. So, I wrote, “Dear Sirs, while I am not a Naval Architect and don’t have a PhD, I do know a little about ice.” I was interviewed in Calgary and in late summer 1984 relocated to St. Johns. The Director never forgot my mention of 2,300 miles by dog sledge. But I had also done my homework. When at the interview, I happened to mention I had already seen the plans and artistic impressions of the new institute, I knew from their reaction that I had just got myself a job.

The next 25 years were a wonderful experience with a great bunch of people. My main role was looking after the Ice Model Test Basin, or just the Ice Tank as it was called. Grown men playing with toy boats in ice, but we tested everything and anything from submarine conning towers to oil rigs, dam fuse gates to oil transfer hoses, ferries, trawlers, cargo ships and even the odd icebreaker or two. Too bad we never had the chance to do the model tests for Boaty McBoatface. I had retired by the time the plans for the new ship were announced but it would have been a fitting ending to a career that essentially started with BAS, over 50 years ago now. Some modeling was in fact done at HSVA, The Hamburg Shipbuilding Research Institute, in Germany of course, the same but very different nation that inspired Operation Tabarin, and the birth of BAS. As a further trivia, at the end of WWII the allies removed the cavitation tunnel (a hefty apparatus used for testing scaled model propellers to improve efficiency and quietness – useful for U-Boats) from Hamburg and brought it to NRC Ottawa. It was then brought to St. John’s when the new facility was opened and with some modernisation is still in use today.

There was field work with NRC too but mostly related to full scale trials of new vessels. My last trip was in 1985 shortly after joining. For 18 years I had spent at least part of every year in the polar regions, and with a young family I was more or less ready to hand off the field work to the younger guys. However, work in sub-zero temperatures continued and work in the Ice Tank and labs was probably colder at times that the guys were experiencing out in the field! I’ve always had a passion for research and working for NRC felt like a natural extension and culmination of those footsteps in the snow that led to BAS and then beyond.