Steve Wormald (continued)

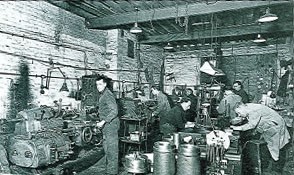

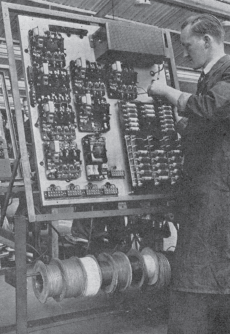

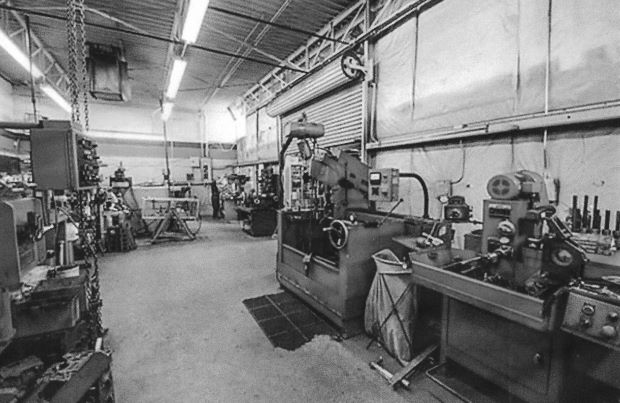

Looking back over the subsequent years, that apprenticeship gave me a superb practical grounding in most things engineering – from sweeping the floor! to the Toolroom with drill stands, lathes and milling machines of all kinds, and precision measurement; then graduating to the three factories, with assembly lines populated by hundreds of women of all ages, shapes and sizes, all building motors from wire upwards (and all out to break the monotony by catching any young passing apprentice off-guard); to control system panel assembly and wiring shops, mostly staffed by “older” apprentices with supervisors; and finally promotion to the Drawing Office, the ultimate goal! Which started work at 8:00am!

From the age of 11, my often monotonous work life was balanced by, initially, Boy Scouts, and camping, every feasible weekend around the UK; this was the time when I met my teenage friends, Rod and Paul, who later became Fids at the same time as I did. Eventually rock climbing came into play, with weekends and summer evenings in the nearby Peak District; in Snowdonia in North Wales, initially being “taught the ropes” with Geoff and Brede Arkless; and then ice climbing in Scotland, after being taught those ropes by Ian and Nikki Clough. We moved on to annual two-week alpine climbing holidays in Austria. Oh, the Freedom.

Throughout my teenage years, my heroes were Mike Banks and Angus Erskine, having read and re-read their book ‘High Arctic’. This had nothing whatsoever to do with the Antarctic, and it was only in later years that I realized that Angus Erskine had actually been Base Leader at Fids Detaille Island – Base W.

My first attempt to ‘break out’ failed miserably, when I applied for a commission in the Royal Navy (on papers signed by my Mum as my Dad refused to do so), given that all the members of the ‘High Arctic’ expedition to Greenland were Navy officers. I believe I passed all the necessary physical, intelligence exercises (crossing river full of alligators with two planks and an oil drum, etc) and written exams; but I came from Yorkshire. At the time, apparently that had vocal drawbacks.

So back to the Drawing Board, and office. By now 21, apprenticeship and technical qualifications completed, and out of parental control, the call of the outdoors called more and more often. We took a monthly climbing magazine, and there it was – The British Antarctic Survey were Recruiting Men to Work in the Antarctic. Trips to Gillingham Street, near Victoria in London, to interview with Bill Sloman and Eric Salmon, two old geezers that at the time we wondered how and why they selected people (see about that here). Eventually, after an interminable wait, Rod, an accountant, was employed as a GA (General Assistant) because of his climbing experience; Paul and I had had the same and identical experience; Paul, a plumber by trade, was employed as a Builder, and, with an Engineering education including Physics, I was hired as a Meteorologist (“Met. Man”).

(None of us realized at that time the implications of this, but Rod was the lucky one, in my eyes at least, because being a GA in Marguerite Bay really meant being a dog driver and having your own team. So my year as a Met. Man at Adelaide meant doing the Met. work (3-hourly observations for 24 hours, one day in four, and all the other Base work), but then spending as much time as possible in the field and on the sea-ice driving the Base dog team, before transferring to Stonington for my second year as a GA! As all four Met. Men at Adelaide were wannabee GA’s, arranging field trips worked out easily; two could easily cover the Met. work for such periods).

The Met. training at the Meteorological Office in Stanmore, Middlesex during the day, and enjoying living in London by night, with its myriad pubs and eventual link up with some second-time (and third and fourth in some cases) Fids, gave us some interesting background and invaluable tips – like which cameras were a “must” before reaching the Antarctic, but not to buy in London because the ship’s Stewards had endless supplies of significantly cheaper (but no doubt still profitable) supplies of Pentaxes, Nikons, Minoltas, lenses for every cause, and Rolex and Omega watches.

The final training was always at an active airport, and instead of Heathrow or Gatwick, I lucked out and drew RAF Valley on Anglesey for a month of “Night Met”, which was a great experience for both life, and acquiring Met. observation skills applied in the real world at night. A colorful and sometimes exciting place to be, as the fighter jets and also RAF Valley Search and Rescue helicopters took off and landed constantly on the brightly-lit runways, in all weathers, on training missions and sometimes for real. This came with an added bonus of some weekend rock climbing with the S & R airmen on their days off.

Then, finally, a week-long induction/brainwashing course at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge University, where we had lectures all day; met all the new Fids from all walks of life – Geologists, Geophysicists, Surveyors, Botanists, Biologists, Glaciologists, Cooks, Carpenters, Mechanics, Builders, Met. Men and GA’s (see above!), all lined up to eventually join either the Shackleton or the John Biscoe in Southampton shortly afterwards; inspected a new set of Pubs by night; and then were locked out by the College wardens; in effect, finally sampling the University experience I had so narrowly escaped, seven years earlier.