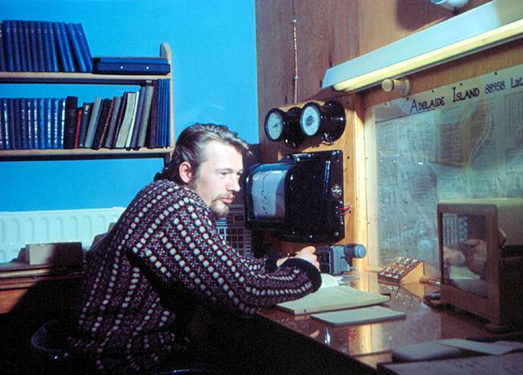

Header Photo: Bill Taylor

History

Adelaide Island was first sighted from the brig Tula in February 1832 when completing a circumnavigation of the Antarctic continent. The ship’s master, John Biscoe, named the land after Queen Adelaide, the wife of British monarch King William IV. (Other views contradict – that the name Adelaide stems from the French surveyor who originally called the island Adelie Land, after all the penguins which resided on it – and that this became corrupted to Adelaide Island after the British arrived).

It was not until the British Graham Land Expedition of 1934–37 that Adelaide was confirmed to be an island separate from the Antarctic Peninsula. The story of the establishment of Adelaide Base T as stated in Wikipedia has now been debunked and here is the actual story:

Establishment of Base T – Adelaide

Site selection, 1961 – Keith Holmes

In his book, the Silent Sound, Cliff Pearce, who was aboard RRS John Biscoe at the time, gave a full and gripping account of how the dogs and men were moved from Wordie House to the unplanned site of Base T on the south-western end of Adelaide Island.[1]

RRS John Biscoe and the site for Base T, on Adelaide Island, February 3, 1961

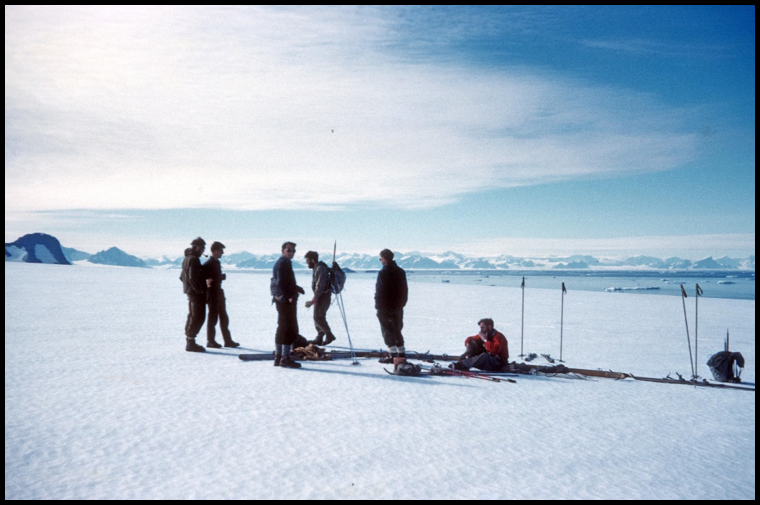

The first landing party on the piedmont of Adelaide Island, February 3, 1961

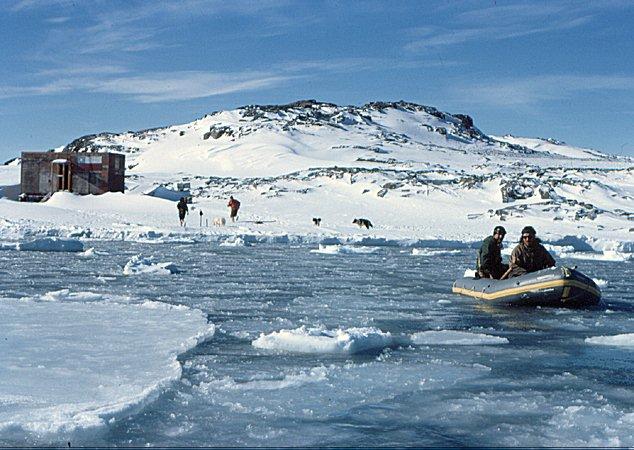

They left the Argentine Islands on January 28th, 1961, when the Survey intended to set up the new base at what was then called access point but is now known as Rothera Point, on the south-eastern side of Adelaide Island. However, Captain Johnston and his ship were unable to break through the pack ice east of Adelaide Island in northern Marguerite Bay, so he and SecFids, John Green, had to search for an alternative site on the island’s southernmost extremity. They found one a mile and a half northwest of Avian Island,[2] and, after a quick examination, Flight Lieutenant David English identified a suitable location where the two single-engined Otter aircraft could be based during the summer season. It lay three hundred feet above sea level, on the Fuchs Ice Piedmont, and could be reached fairly easily from the rocky foreshore up a moderate slope. After “full and frank discussion,” it was decided that the new hut would be built on the rocks below it. It had enough rocky space upon which to build the first huts, and, above all, it gave easy access to the Fuchs Ice Piedmont, from where the aircraft could fly.

Pack-ice in Laubeuf Fjord on February 7th, 1961

What they didn’t know at the time was whether there was a feasible route from there, through the mountain chain that runs the length of the island, and down the Shambles Glacier to Rothera Point on Anchorage Inlet. This had been identified as long ago as 1957 as a desirable site, and was the one preferred by those who would actually winter at the new base. It was hoped that men with two dog teams could soon test this route after being dropped off on the fast ice in Laubeuf Fjord, but the ship was still unable to reach a suitable point when it made the attempt on February 7th.

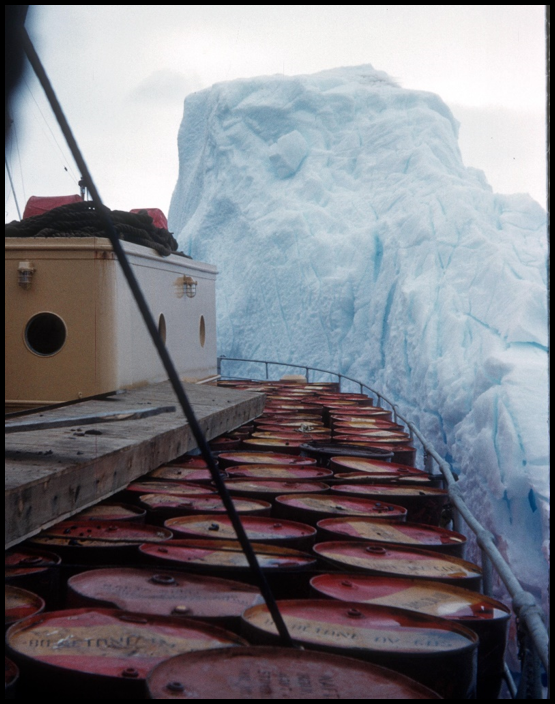

An iceberg nudging RRS John Biscoe, in “Iceberg Alley” off Base T

One major drawback to the site was the tendency of the bay to fill with brash ice and small icebergs – as predicted and shown in an aerial photograph taken soon after the dogs had been spanned.[3]

Men, materials and dogs for the new Base T were unloaded from RRS John Biscoe, in “Iceberg Alley” off Base T.

First Hut – Stephenson House – Keith Holmes

(Photo AFW61, by Alan Wright)

Men, materials, and dogs for the new Adelaide Island Base were unloaded from RRS John Biscoe between February 3rd and 10th, 1961. Alan Wright spent the austral winters of 1961 and 1962 at Base T, and some of his photographs record the building of Stephenson House, the first of a small conglomeration of huts that accumulated over the years. In his first year, there were only six men, but in his second there were eleven.

In 1964, “Black Adders” had no fewer than 21 winter Fids, overseen by the redoubtable John Cunningham.

See more of the construction of Stephenson here

Aircraft History

Over time, the website will be populated with a History of each aircraft involved in Marguerite Bay operations, starting in 1946. Most will be added as a small entry, with a lead off to what is in some cases an extensive history of some of the aircraft, for those who wish to read them.

These records are available in a BAS Archives Report supplied by Keith Holmes, which was compiled by Douglas A. Rough – in-depth researcher into Falklands Islands Civil & Military Aviation including BAS.

During the 1960s, the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) owned three single-engined de Havilland Otter aircraft, whose construction numbers were; 294, 377, and 395.

The Single-Engined Otters – Keith Holmes

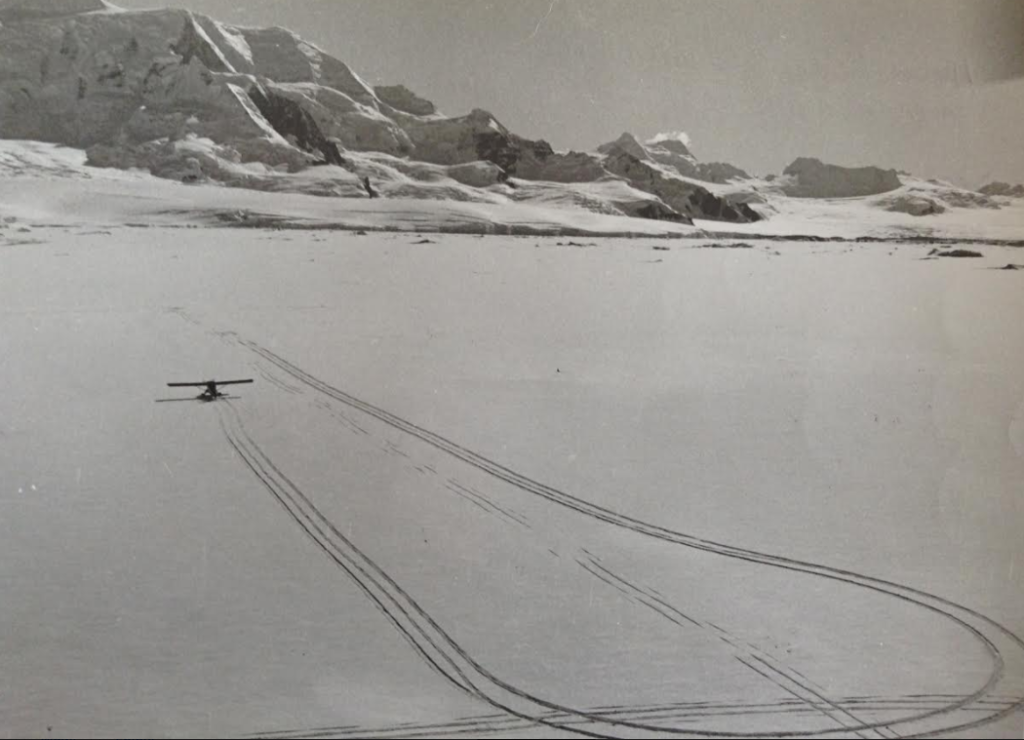

The single Otter was a fairly simple, and robust, piston-engined aircraft that could be fitted with floats, or in the Survey’s case with skis and wheels to land on both snow and land, and above all it was large enough to carry a complete twelve-foot Nansen sledge, its nine dogs, and its driver (a total payload of about 1100 or 1200 lbs) over a range of roughly 150 miles.

The type had already proved its worth in the same sector of the Antarctic. In 1957 the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition had one at Shackleton Base, on the Weddell Sea, to the east of the Antarctic Peninsula, and the United States used three of them to support its 1957 programme for the International Geophysical Year at Ellsworth base, to the west of Shackleton.

To give a Fids-oriented account of the Survey’s three specimens, I have drawn heavily on two very useful sources of information.

Firstly, a comprehensive account of all the Survey’s aircraft up to 1986 was compiled by Douglas Rough and published in an appendix to the book “Falklands – the Air War”[1]. It records, inter alia, the repeated cock-ups that bureaucrats in the Falkland Islands made when registering and painting their aircraft, the lesson being that it is best to use construction numbers rather than registrations when referring to specific aircraft.

Secondly, there is a fascinating website (dhc-3archive.com) which is dedicated to the marque and gives splendid photographs and much detail about most of the 465 examples that were manufactured between 1951 and 1967.

For the individual BAS Single Otter aircraft stories:

VP_FAJ – Reg #1342 – Landed and sank at Argentine Islands and never made it to Marguerite Bay

Read on (to Follow)

(Photo: David Bridgen)

VP-FAK – Reg # 294 aka “Bas Blue Label” See Winter 1966

VP_FAL – Reg # 377 aka “Bas Red Label”

VP-FAM – Reg # 395

VP-FAK Reg# 294 DHC-3 Single Otter

VP-FAK DHC-3 Otter #294 made its first test flight at Downsview on 17 October 1959 and was delivered to BAS on 5 November 1959 registered VP-FAK (aka “Bas Blue Label”). It was packed into a crate at Downsview, as was Beaver VP-FAJ (1342) which had been purchased at the same time. Both were shipped to Deception Island in the Antarctic on board the MV Kista Dan, arriving January 26th 1960. They were re-assembled and entered service. VP-FAK’s first flight in the Antarctic was on 3 February, 1960.

VP-FAL#377 DHC-3 Single Otter

Registered as VP-FAJ but painted and flown as VP-FAL, DHC-3 Otter, Construction No. 377. Purchased 1960. Operated in the same way as VP-FAK. Crash landed in poor visibility at Adelaide, 28 December, 1964. Written off and destroyed.

Summer 1960/1961 – Establishment of Fossil Bluff

Flying out of Adelaide from the Fuchs Ice Piedmont, VP-FAK and VP-FAL provided extraordinary service during the summer, flying over 13,000 nautical miles, in 130 flying hours, airlifting 23 tons of materials fuel and supplies, plus people, to the remote site at Fossil Bluff to build and service the hut. for the first Wintering Party. Read the story on: Fossil Bluff 1961

The need for Change

In 1973, it became increasingly apparent that the skiway and access to it at Adelaide were becoming problematical. After investigations and surveys at Rothera in 1974, work began on establishing a new base there, and operations were moved to the new Rothera Research Station (Base R) during 1975-76. Adelaide Base was transferred to the Chilean authorities in 1984, when it was renamed Teniente Luis Carvajal Villaroel Antarctic Base. The base was then used as a summer only station by the Chileans. The skiway deteriorated further, leading to the death of a Chilean air mechanic, when he fell down a crevasse; the skiway and ‘ramp’ to the base from the plateau all became so unstable that the Chilean Air Force ceased operating there. The Chilean Navy continues to visit the base during the summer to ensure it is in good order.

Winters:

1961

Base Commander – Frank Preston

| Crouch, A. (Alan) | Meteorologist |

| Dewar, G.J.A. (Graham) | Geologist |

| Fitton, G.F. (Frank) | Radio Operator |

| McCallum, H.C.G. (Gordon) | GA |

| Preston, F. (Frank) | BL, Surveyor |

| Wright, A.F. (Alan) | Surveyor |

Topographic Survey

1962-3 Preston and Wright at Adelaide Island

After the new base was established on the SW point of Adelaide Island, Frank Preston and Alan Wright began a Systematic Triangulation survey to connect and extend the work of the surveyors from Detaille and Horseshoe. An astro-fix was observed during the winter and local mapping to assist the geologists.

A Winter’s Day – Gordon McCallum

The darkness was split by a shaft of light as the door of the Antarctic base opened. A man stood outlined for a moment, sniffing the cold air, feeling it freeze on the hairs inside his nose. He looked up at the star-bright sky and muttered through the wool of this balaclava, “Temperature’s going to drop”.

He waded through the snow, which was deep and soft, almost knee high. The sealskin boots drawn tight round his calves kept his feet dry but he occasionally stepped into a bigger drift which forced him to flounder and fight his way to firmer ground, red-faced and exasperated.

After fifty yards of this hard work he started moving carefully placing his feet quietly into the snow as he gradually approached a ten-foot-high cage. In a corner of the cage a wooden kennel was almost completely covered by the snow. Creeping as near as possible he stood and listened. At first only the puttering of the diesel generator carrying from the hut broke the silence but suddenly a chorus of squeaks issued from the box. He stood for a moment, a quiet smile spreading over his face. Satisfied with the result of his expedition he turned and using the tracks of his outward journey quickly walked back to the hut.

Depot Laying on Adelaide – Gordon McCallum

Two men, 20 dogs, two sledges and one Nansen man-haul sledge – a starting load of 1,700 lb becoming 2,300 lb when we picked up 600 lb at the top of the hill three miles away. The power pack consisted of two dog teams, 11 in my team and nine in Frank Preston’s. Our task was to take the load and lay a depot north of Adelaide Island base.

There could not be a greater difference in dog teams than between the Counties driven by Frank and my team the Giants. The Counties were old, powerful, reliable and well trained. Eight of the Giants on the other hand were barely a year old and had only 200 miles sledging to their credit. When asked how I drove such a young team my standard answer was “Approximately!”

The sky that morning was overcast and we only had the gloomy light of an August winter’s day to help us load the sledges. The wind was slight but blowing from the north, and our course would eventually be upwind. The weather looked unpromising but we decided to harness up and travel as far as we could. As we ground up the first steep slope out of base we passed the other dogs on the spans and I avoided the hurt reproachful looks that were thrown at me by 20 miserable huskies temporarily confined to barracks.

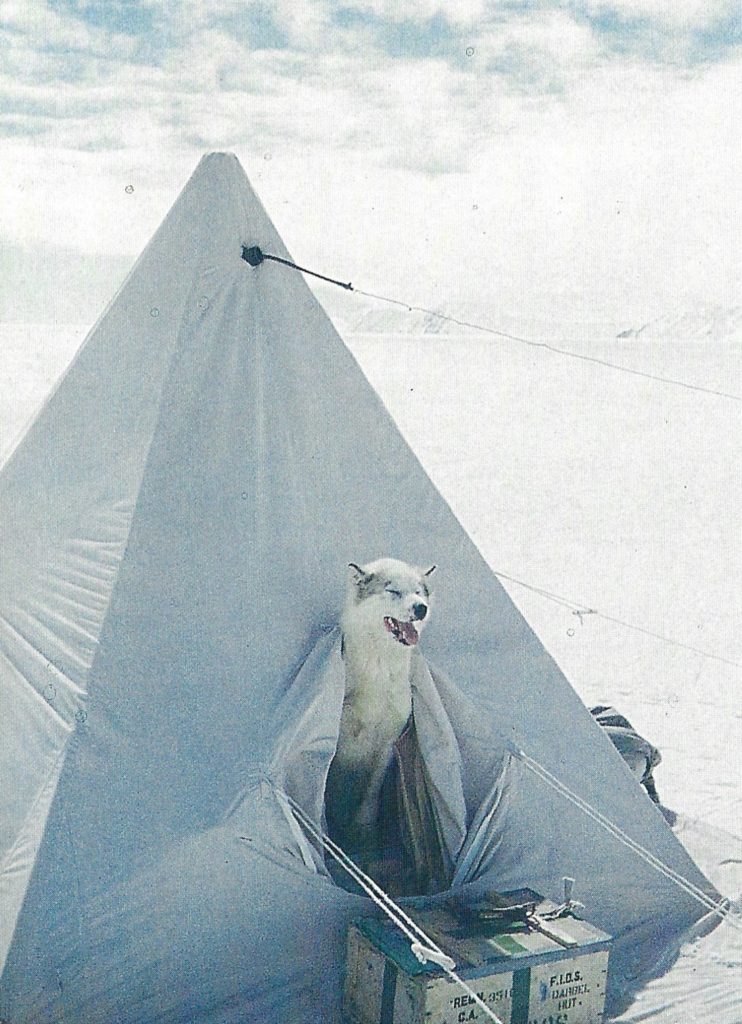

Pups – Gordon McCallum

Pups played noisily on the roof of the hut, stealing food, chewing anything they found lying around, and generally getting in everyone’s way. The were a major nuisance as well as being the biggest boost to morale any Antarctic base could have.

‘Juno’ – Gordon McCallum

On two occasions, bitch ‘Juno’ was mated at Adelaide in 1962 as part of the breeding program. She was given a comfortable kennel, fed extra rations, vitamins and cod liver oil. Her coat became glossy, her eyes maternal and she expanded appropriately. She seemed to enjoy the extra attention and the viewpoint from the top of the kennel.

Her second phantom pregnancy was however her last chance at an easy life. She was charged with “Fooling the dog man and destroying his credibility”, found guilty as charged and sentenced to a three-month survey trip on a diet of dried pemmican.

Dog slopes at Adelaide – Alan Wright

Dog Sense

It was almost uncanny the way the dogs tethered at base would sense a returning sledge party, whether it was by incredible hearing or a sixth sense I never knew. Long before us humans could know the base dogs would get very excited and would all howl – sing – in unison. The only other occasion when this happened was on a clear, very cold and calm night. To have 60 dogs singing together in tune (?) was a memorable sound; even more memorable was the way they would all stop at the same instant.

‘Fury’ – Gordon McCallum

One morning I crawled out of the tent to find that “Fury” was lying in a pool of blood on the snow. Slipping on my boots, ignoring my outer clothing, I fought my way out of the sleeve doors and ran over to the silent tableaux. I had seen huskies recover from the most dreadful wounds, but this one was bad. I moved to lift Fury’s head, taking it gently in my hands and stroking his ears. He tried to lick me but gave up after his first effort and lay still. Frank Preston helped me pick him up and we carried him into the tent. No large wounds were immediately visible, the only remarkable features being two blood icicles, about three inches long, hanging just above and behind the point of his chest bone. I hesitated to break the clotting and decided to let the icicles thaw naturally. I covered Fury with an old anorak and set about preparing the breakfast porridge.

Painfully, about half a spoonful at a time, I eased some milk down his throat but he choked frequently and after a bit I gave up. Frank went outside to dig out the sledge and tent in preparation for the time when we could travel. The temperature was rising but Frank said he thought we were in for more snow and would not be able to travel for some time.

‘Mimi’ – Gordon McCallum

In the height of summer, it is often easier to travel at night when the temperature drops and the surface freezes. The tent door is usually kept open while we sleep because because it gets very stuffy, and on this occasion I was awoken very suddenly by Mimi jumping on top of me and proceeding to give my face a wash with her large tongue.

My arms were trapped inside my sleeping bag, and I was held down by nearly 100 lbs of husky. Alan Wright woke up and tried to throw her out. She identified his actions as a game, and in her excitement peed copiously over my sleeping bag. The more he tried to push her out the more excited she became and the more she peed.

She then decided to sprint in a circle round a six-foot square tent. Pots, pans, radio and primus were all sent flying. In desperation we both dived out of the tent and left her in command….

1962

Base Commander – Graham Dewar

| Bryan, R.B. (Rorke) | Meteorologist |

| Dewar, G.J.A. (Graham) | BL, Geologist |

| Gibbs, F.J. (Fred) | GA |

| Hounsell, D.J. (David) | DEM |

| Killingbeck, J.B. (John) | GA |

| Leckie, R.H. (Harry) | Meteorologist |

| Nash, D.F. (David) | Surveyor |

| Nixon, J.B. (Brian) | GA |

| Smith, E.W. (Ted) | Radio Operator |

| Woolley, W.S.L. (Stan) | Meteorologist |

| Wright, A.F. (Alan) | Surveyor |

Topographic Survey

1962-3 Nash and Wright

The arrival of Tellurometers and the RRS John Biscoe to carry out hydrographic survey, enabled nine lines to be measured to offshore island stations. The triangulation programme was changed to a traversing scheme around the flanks of the mountains of Adelaide Island.

Based initially on RRS John Biscoe and later on HMS Protector, Dave Nash, Alan Wright, Ivor Morgan, Bob Metcalfe and Ken Blaiklock traversed west to Amiot Islands and south to Faure Islands, and later the ships provided logistic support for the final observations in the north of Adelaide Island.

1963

Base Commander – Harry Leckie

| Bryan, R.B. (Rorke) | Meteorologist |

| Cousins, M.J. (Mike) | Meteorologist |

| Geddes, W. (Bill) | Radio Operator |

| Gibbs, F.J. (Fred) | GA |

| Gill, R.V. (Ron) | Tractor Mechanic |

| Lambert, K.L. (Ken) | DEM |

| Leckie, R.H. (Harry) | BL, Meteorologist |

| Morgan, I.P. (Ivor) | Surveyor |

| Nash, D.F. (David) | Surveyor |

| Palmer, R.G. (Dick) | Tractor Mechanic |

| Shirtcliffe, L.J. (Jim) | GA, Builder |

| Woolley, W.S.L. (Stan) | Meteorologist |

Topographic Survey

1963-4 Nash and Morgan

No air support was available this season and the surveyors sledged to Fossil Bluff. From Fossil Bluff Ivor Morgan and Dave Nash sledged and recced north setting 3 stations on the east side of the Sound. A route onto the plateau at 71.5s was recced and 2 stations for a trans plateau traverse were established.

Not a Sledge Dog at All, but: – Stan Woolley

Peso was certainly not a husky. Her main likeness was to a spaniel. She was generally understood to have been acquired by FIDASE in Montevideo, for a peso, and to have come south on that expedition’s ship, the ‘Oluf Sven’.

In his book ‘Wings Over Ice’, Pete Mott, the leader of FIDASE, writes-:

FIDASE put Peso ashore at Port Lockroy in early 1957. In the 61/62 season Port Lockroy was closed and Peso came down to Base T, Adelaide Island. I believe that in those years Peso had also managed to spend some time at Base F Argentine Islands.

A pet dog can pose some problems on a base. These are best solved if the animal has a clear master to relate to. Peso was fortunate in this respect because Brian Nixon had also come to Adelaide Island from Port Lockroy and he made an efficient and unobtrusive job of looking out for Peso’s interests and needs.

I also got along well with Peso, and I enjoyed taking her on occasional walks in the general area of the base. When the sea was open she particularly enjoyed a trip in the base dinghy, across to Avian Island, where an affable amble around the perimeter of the Adelie rookery was much to her liking.

On 23rd January ’63 I left base accompanying Graham Dewar, the base geologist, and his team, the ‘Citizens’, for a short field trip from which we returned on 9th February.

1964

Base Commander – Johnny Cunningham

| Armstrong, E.B. (Barry) | Surveyor |

| Ashworth, H.D. (Harry) | Meteorologist |

| Ayling, M.E. (Mike) | Geologist |

| Back, E.K.P. (Kenn) | Meteorologist |

| Bottomley, A. (Alec) | Meteorologist |

| Common, J.H. (Jim) | GA |

| Cunningham, J.C. (Johnny) | BL |

| Darnell, K. (Ken) | Cook |

| Gardner, J.L. (Jimmy) | GA |

| Geddes, W. (Bill) | Radio Operator |

| Horne, R.R. (Ralph) | Geologist |

| Owen, R.E. (Roger) | Meteorologist |

| Pagella, J.F. (Julian) | Geologist |

| Palmer, R.G. (Dick) | Tractor Mechanic |

| Pimm-Smith, B. (Brian) | Meteorologist |

| Rice, M.H.C. (Mike) | Medical Officer |

| Rider, A.H. (Tony) | Surveyor |

| Smith, W. (Bill) | GA |

| Tait, J.E. (John) | DEM |

| Thomson, M.R.A. (Mike) | Geologist |

| Todd, D.T. (Davy) | GA |

Topographic Survey

1964-5 Armstrong and Rider at Adelaide Island

With air support Barry Armstrong and Tony Rider measured eight Tellurometer lines in a traverse running east to Mount Jackson with the final station at 2740m. Two sun-fixes helped to roughly position this isolated piece of work.

(How this piece of survey work came to be prioritised might be the result of having a famous climber as BC and Mount Jackson at 3184m thought to be the highest peak in the Antarctic Peninsula. In 2017 it was demoted into second place below Mt Hope at 3,239m. John Cunningham led a first ascent of Mount Jackson in Nov 1964, and Mt Hope was first climbed by Keith Holmes and Mike Cousins on Christmas Day 1965. This also highlights the less than perfect heighting used on some of the early surveys)

The primary task was Tellurometer traversing to link the earlier triangulation schemes from Detaille and Horseshoe, this was recced in the winter of 65 but work was held up when sea ice problems marooned the party on Detaille Island.

Mike Cousins made a “sketch” survey of the Bingham Glacier on a geological trip, heights obtained using an erratic aneroid barometer.

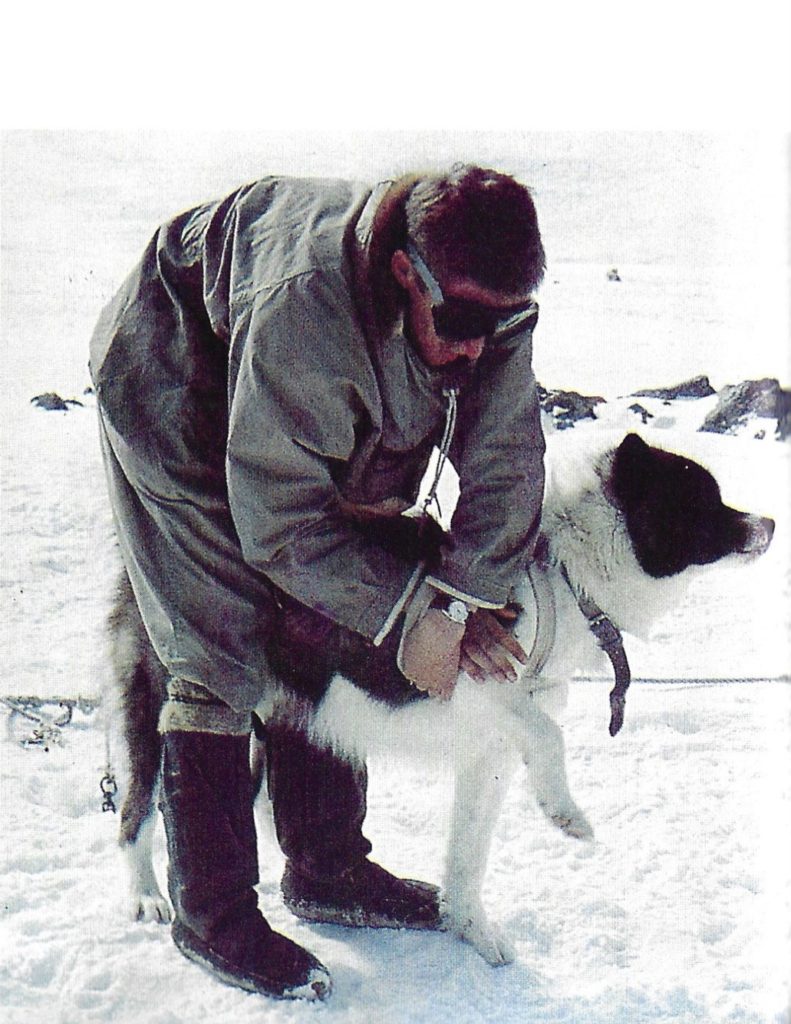

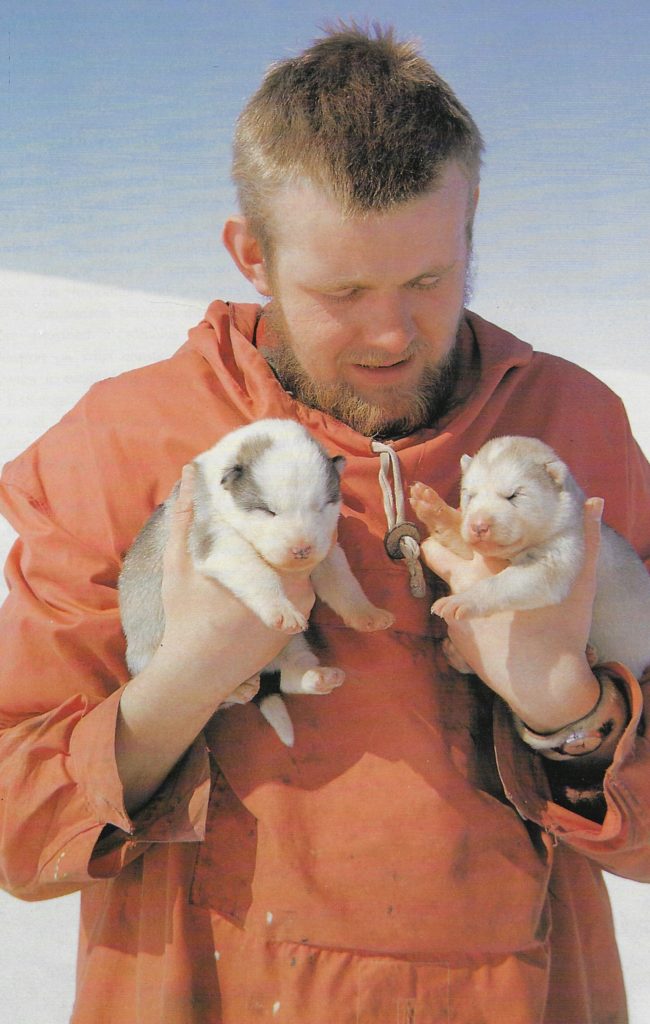

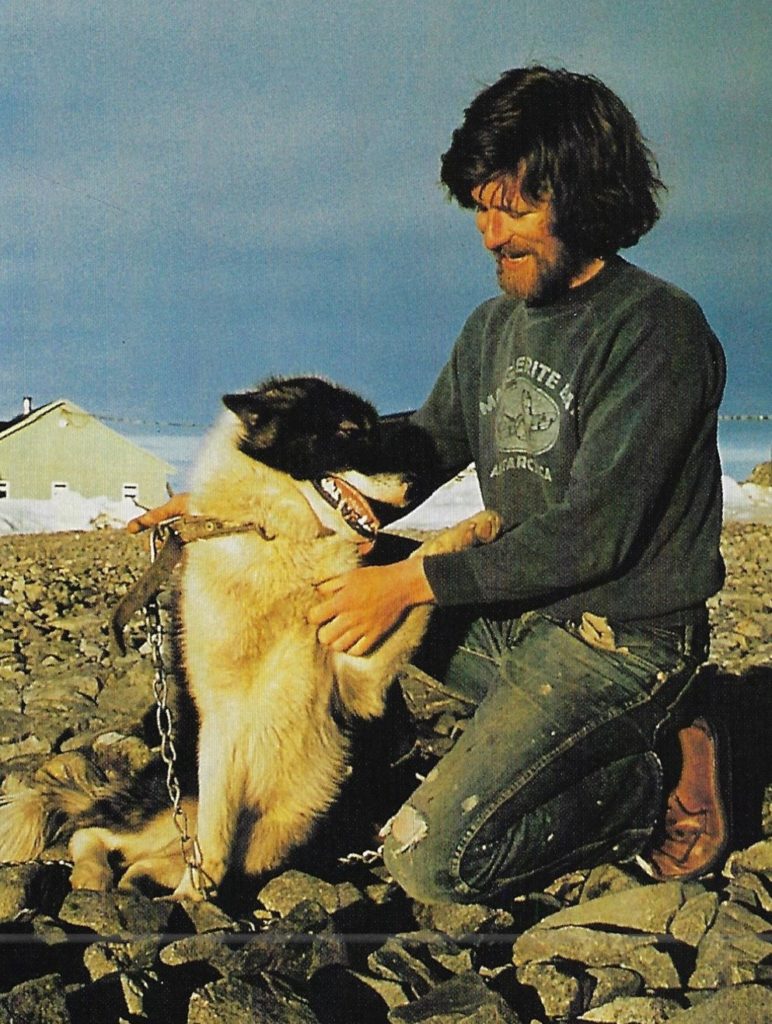

Pup Breeding at Adelaide

Adelaide was a steady breeding base for pups heading for the field from Adelaide or Stonington. Typically the pups were run in teams from the age of six months onwards, joining the teams for local runs on the sea-ice and on the Fuchs Ice Piedmont, and then they would eventually head out for field programs on Adelaide, in the fjords, and from Stonington south to the Plateau.

The gestation period for huskies is 63 days and mums were generally drawn out of the team at seven weeks. An average litter was between four and six pups, although the record was 14 pups born to a bitch named ‘Joy’. On very long journeys there were of course occasions when both mating and pupping took place in the field. Mums were happy to go back to work after a day or so’s rest, but would usually be returned, with pups, to base at the earliest opportunity.

The pups weighed about 12 ozs. at birth, but doubled this within three days. Rickets was quite common in the early days so the pups would be fed extra vitamins and cod liver oil.

Roger Owen, Adelaide Met, 1964

December

Relief By Air from Fast Ice – Keith Holmes

At the end of 1964, it was imperative to restock Base T with avgas to replace the hundred drums that had been buried under snow earlier in the year, and Captain Tom Woodfield started his approach to Adelaide Island with RRS John Biscoe during December.

(Photo: Keith Holmes)

However, difficult ice conditions persisted, and, over nearly three weeks, he was repeatedly guided by advice from the pilots of the two single-Otter aircraft, who made reconnaissance flights to determine the best route. Incidentally, this season was also, I think, the very first in which BAS headquarters had access to satellite images, and could give guidance to ships’ captains from London (which I’m sure they found a mixed blessing!).

Aircraft VP-FAL DHC-3 Otter #377 (aka “Bas Red Label”)

December 28th, 1964, the tail-ski was ripped off VP-FAL, the undercarriage struts driven up through the airframe and the rear fuselage twisted in a heavy landing accident at Adelaide. The pilot (Flt Lt E.J.Skinner) was unhurt but the aircraft, which had fallen some 30ft into a dip in the snow and ice not seen from the air, was deemed to be “beyond economical repair” and SOC (Struck off Charge).

1965

Base Commander – Len Mole

| Back, E.K.P. (Kenn) | Meteorologist |

| Common, J.H. (Jim) | GA |

| Davies, T.W. (Tom) | MO, Physiologist |

| Green, G.M. (George) | Tractor Mechanic |

| Miller, T.H. (Tom) | Cook |

| Mole, L.U. (Len) | BL, Meteorologist |

| Noel, J.F. (John) | Radio Operator |

| Owen, R.E. (Roger) | Meteorologist |

| Warr, M.E. (Mike) | Meteorologist |

Base Life

The following random excerpts describe typical activities and thoughts during the winter of 1965, with Kind Permission of Mike Warr (who spent his first winter at Deception Island Base), from his book “South of Sixty”, in which he describes his second winter at Adelaide.

“April came in with a bang when we moved some heavy metal pup-pen sections, and one six-foot piece tipped sideways onto my head. Roger’s shoulder took most of the weight. There was some blood and I received two stitches. I now displayed a finger scar from Deception Island and a small depression on top of my head from Adelaide Island. On the 3rd of April we lit magnesium flares as the Shackleton left for the year. The crew responded with rockets. We were on our own.”

“Six of us talked until 2 in the morning. The duration of the talking and the inconclusive outcomes said more about the state of our minds than our ability to solve anything; we talked to bolster ourselves against the upcoming winter isolation. The ships should return in nine or ten month’s time. The nine of us on base would have to depend on each other; there would be no Argentinean or Chilean winter distractions. For Roger, Kenn, and Jim their base had shrunk from twenty-one people to nine; there would be fewer people to interact with”

1966

Base Commander – George Green

| Bird, P.G. (Peter) | Meteorologist |

| Chappel, B.M. (Bernard) | Meteorologist |

| Green, G.M. (George) | BL, Tractor Mechanic |

| Hay, P.R. (Peter) | Meteorologist |

| McLaren, N.O.S. (Nick) | Radio Operator |

| Miller, T.H. (Tom) | Cook |

| Wilkinson, F.W.A. (Eric) | Meteorologist |

A Few Recollections From My Time Spent with the BAS Huskies – Bernard Chappel

Having read the article penned by A.C. Palmer (Veterinary History Vol. 18 No. 2 pp 184-195), it was suggested by the Editor, John Clewlow, that as a follow-up, I should recount some of my experiences with Huskies during my time spent with the British Antarctic Survey (B.A.S.) from 1964 through to 1967.

The majority of my time spent with B.A.S. for the first summer was employed as Cook at Base ‘B’ on Deception Island, after which I took on the role of Meteorologist for the remainder of my time, wintering also at Base ‘T’ on Adelaide Island during my second year.

The role of Dog Handler was presented to me virtually from the time I set foot on land at Deception Island. The outgoing Dog Handler, Mike Warr, was on his way to Adelaide Island within a few days and it was paramount for him to hand over to an unsuspecting individual as quickly as possible.

1967

Base Commander – Alec Bottomley

| Barlow, J. (John) | Meteorologist |

| Beard, J.D.G. (John) | Tractor Mechanic |

| Bottomley, A. (Alec) | BC |

| Bowen, D. (David) | Builder |

| Darroch, D.W. (David) | Radio Operator |

| Gibson, B. (Bryan) | Cook |

| Ledingham, R.B. (Rod) | Meteorologist |

| Meeds, F.G. (Francis) | DEM, Tractor Mechanic |

| Salter, D.F. (David) | Meteorologist |

| Wilkinson, F.W.A. (Eric) | Meteorologist |

Aircraft VP-FAM – DHC-3 Otter, c/n 60-395

Purchased 1967, second-hand, from Royal Norwegian Air Force, to replace VP-FAK. Arrived crated at Deception Island, December 1967. Removed when volcano erupted in same month and shipped to South Georgia. Returned to Deception Island for assembly, December 1968. Operated from Adelaide Island. On 3rd March 1969 Otter VP-FAM took off from Stonington with five souls on board.

The object of the flight was to survey the sledging route to Armadillo depot and to place a supply of fuel and food at the depot. Sixteen minutes after take off, at a height of 5,200 feet, there was a sudden loss of power. The nose of the aircraft was lowered to try to maintain speed, but due to the proximity of high ground, there was no other choice but to attempt a forced landing. There was little time to chose a suitable landing site and the Otter was force landed in the only available area, at an indicated altitude of 4,800 feet. The ground run was fairly short due to the landing being made in an uphill direction, but the surface was extremely rough and the undercarriage collapsed almost immediately after landing. The personnel on board were unhurt, but the Otter was wrecked. It had total airframe hours of 2,335 at the time of its destruction.

Read more about VP-FAM here….

Read more about the forced landing here….(to follow)

Aircraft VP-FAN – Pilatus Porter (” Establishing Porter Depot”)

On 26th February 1968, the BAS single-engine Pilatus Porter piloted by RAF pilot John Ayers landed on the Grahamland Plateau at the junction of the Millet and Meikeljohn glaciers in order to pick up a geological field party consisting of Rod Ledingham and Graham Smith with their team of 8 dogs.

During the subsequent take-off, an under-carriage weld failed, causing a ski to turn outwards, and in bringing the slewing aircraft under control, the tail ski was torn off – damage that could not be repaired in the field.

However, John Ayers assessed that with skis removed, the crusted surface might allow a take-off on wheels, and this nearly succeeded until a wheel broke through the crust, tipping the plane onto its nose and bending all three propellor blades.

The location where the Turbo-Porter crashed was named “Porter Nunatak” by Flt Lt Ayers and is still referred to by that title but is not listed as such in G. Hattersley-Smith’s 1991 definitive publication on British Antarctic Territory (BAT) Place-Names.

The crashed aircraft from thereon became to permanent marker for Porter Depot.

Read more….about VP-FAN…

The full story of that journey and winter is told by Rod Ledingham in his book “Abandoned at Fossil Bluff” (available online to purchase for download) : https://www.timbowden.com.au/2016/03/30/abandoned-at-fossil-bluff-a-remarkable-account-of-antarctic-survival/

1968

Base Commander – Don Parnell

| Bowen, D. (David) | Builder |

| Collings, O.J. (Owen) | Carpenter |

| Elliott, M.H. (Mike) | Geologist |

| Gibson, B. (Bryan) | Cook |

| McKeith, A.D. (Ali ‘Bugs’) | GA |

| Meeds, F.G. (Frank) | DEM |

| Parnell, D.S. (Don) | BC, Radio Operator |

| Rinning, D.J.D.Y. (Dave) | Tractor Mechanic |

| Sheldon, E.B. (Brian) | Meteorologist |

| Willey, I.M. (Ian) | Meteorologist |

October 8th – Mt. Bouvier

By Dave Rinning and Ian Willey, based on an article published in the Scottish Mountaineering Club Journal by Alistair “Bugs” McKeith

(Photo: Dave Rinning)

The long dark Antarctic winter on Adelaide. Ten dismal faces. Ten conflicting personalities. And one of the worst winters recorded on the island, exposed as it is to the first onslaught of hoolies (note 1) from the open ocean. Grey skies and winds gusting to 140 m.p.h. Freak low temperatures, cracked pipes, frostbitten toes. Freak high temperatures, driving rain and feet of slush, flooded huts. Freak high tides, 40-foot waves, huge blocks of ice exploding on the rocks, the water sucking at the very foundations of the huts. And with each new hoolie, the blinding drifting snow, accumulating and lying 30 feet deep on the deck, engulfing the huts. And for a brief instant the sun shines, the temperature drops, the og (note 2) freezes and imprisons the drifting bergs; then just as suddenly the sky blackens, the wind howls, the ice cracks and disappears and the ironical rain lashes down. ‘What are we doing here?’

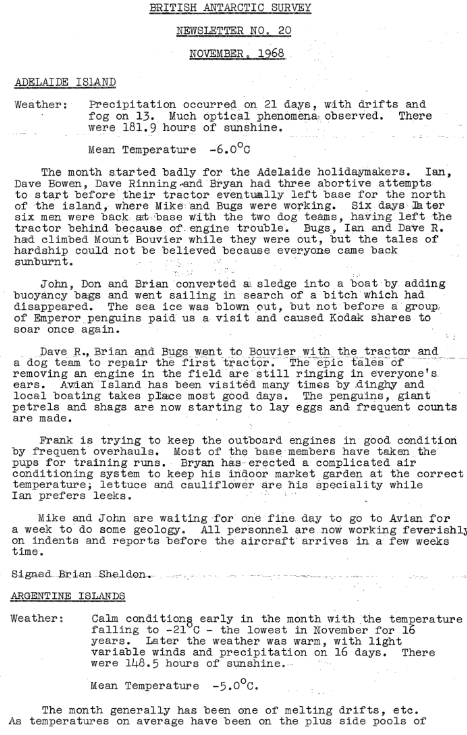

BAS Newsletter – November 1968

Read More November Newsletter here

Summer Flight Operations

VP-FAM – Marking Beehive Depot

During 68/69 summer flying season, the piston Single Otter VP-FAM became a depot marker at Beehive on the Plateau above Stonington, .

and VP-FAO – “The Larsen Ice Shelf Incident“

This story was compiled by Bill Taylor, in cooperation with Ian Willey, Dave Rinning and others, and including extracts from multiple Base Reports, at Adelaide, Stonington and Fossil Bluff

On 10th December 1968 (Austral mid-summer with 24 hours of daylight) a brand-new, BAS de Havilland Twin Otter field-support aircraft with 6 men on board, set off from “Base T”, Adelaide Island (Latitude 6746S, Longitude 6855W) bound for Fossil Bluff (Latitude 7120S 6817W) on what should have been a routine flight. Having failed to get below the cloud and find Fossil Bluff, the plane tried to return to Base T, but this too was a failure. Five-and-a-half hours later, flying blind with only half an hour’s fuel in the tanks, the aircraft made a spiralling, slow descent and a forced landing in whiteout conditions. The pilot believed he had landed on the Wordie Ice Shelf, on the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula. In reality he had landed on the Larsen Ice Shelf – on the east coast. How could this have happened? Without fuel, how would the aircraft get back to Adelaide? The answers to these questions make for an interesting tale …

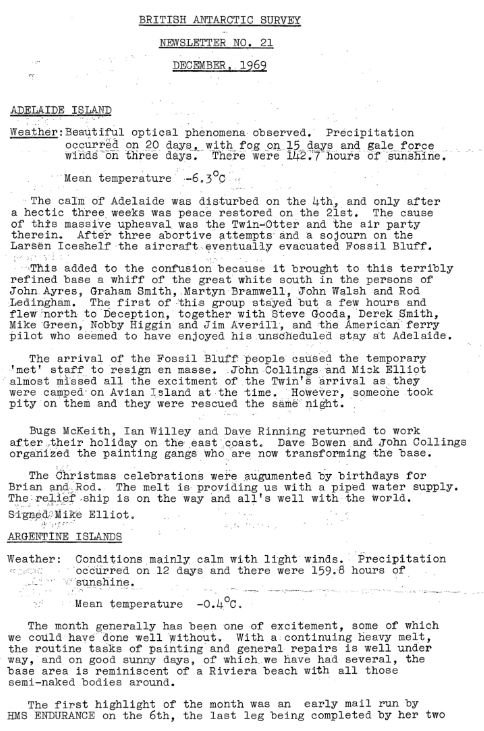

BAS Newsletter – December 1968

Read More December Newsletter here

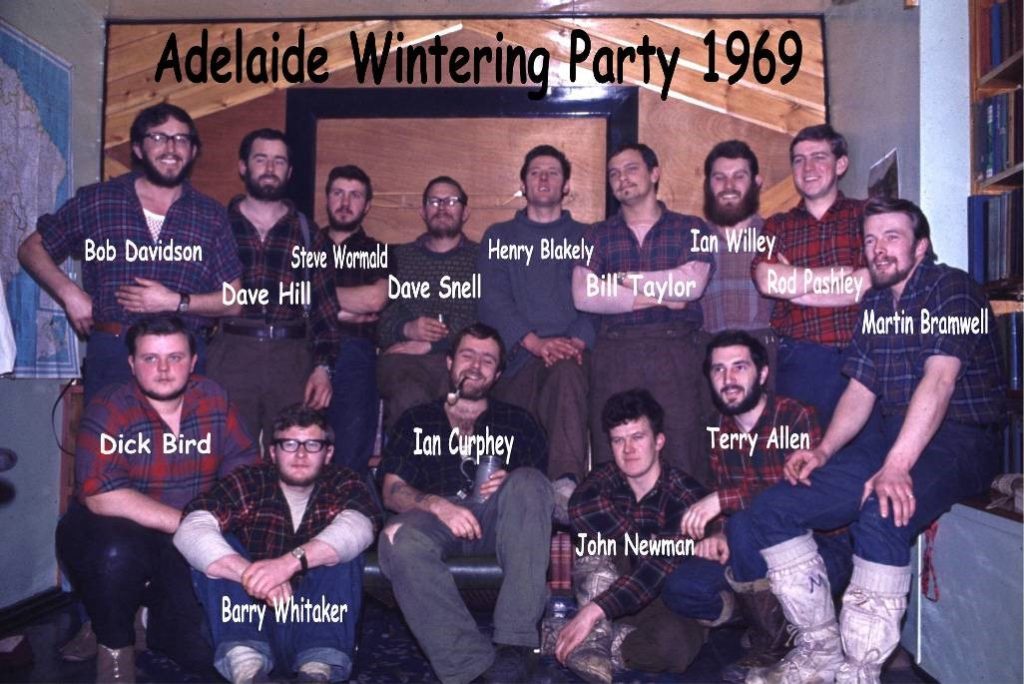

1969

Base Commander – Ian Willey

| Allen, T.R. (Terry) | MO, Physiologist |

| Bird, R.J. (Dick) | Cook |

| Blakley, H.J. (Henry) | Builder |

| Bramwell, M.J. (Martin) | Meteorologist |

| Curphey, I. (Ian) | GA |

| Davidson, R.W. (Bob) | Radio Operator |

| Hill, D.J. (Dave) | Builder |

| Newman, J. (John) | Tractor Mechanic |

| Pashley, R.C. (Rod) | GA |

| Snell, B.D. (Dave) | Radio Operator |

| Taylor, W. (Bill) | Meteorologist |

| Whittaker, B. (Barry) | DEM |

| Willey, I.M. (Ian) | BC |

| Wormald, S. (Steve) | Meteorologist |

FIT AS FIDS

Review of Medical Problems MB, Base T, 1969 – Terry Allen

FIDS tend to be fit, but that does not stop a range of medical problems, usually minor, but occasionally major, being encountered by an MO.

My year was certainly less traumatic than that experienced by my predecessor, Mike Holmes, MO Stonington, who had to deal with the saga at Argentine Island Base, which, in effect, turned the base into a hospital laboratory and nursing station. But, that is another story.

For me, medical input started soon after arriving at Adelaide.

A crewmember from one of the ships developed appendicitis and was deposited on the base. The medical room was converted into a mini-hospital. I elected to treat the man with intravenous antibiotics, despite my experience in operating for such problems in the UK. This was to the dismay of the gathered FIDS, who would have much appreciated the instructional and photographic opportunities of observing abdominal surgery at first hand, as it were.

Things went well, and the crewmember was eventually dispatched back to the ship, with instructions to get it all checked out in London.

Autumn Journeys on Adelaide – Ian Curphey

While we had been away, life at Adelaide had been hectic. One of the men had broken his leg and the second cook off the ‘Biscoe’ had developed appendicitis. Terry Allen, our base doctor, was all for operating and had even arranged for Mike Holmes, the outgoing doctor from Stonington to help him, but in the end, decided on a less drastic and non-invasive stratagem. I think Mike Holmes was disappointed so as a sort of compensation, they decided to perform vasectomies on our dogs. (This wasn’t really a flippant whim; our dogs had inbreeding problems and a program of neutering most of our huskies was in progress). New breeding stock was to be introduced the following year. Vasectomies were preferred to normal neutering, as no one wanted to interfere with the personality of our magnificent working dogs.

From my diary:

‘During the afternoon I helped in the ‘surgery’ (the carpenter’s workshop). Amazingly simple. Just make the dogs dopey, then knock them out with pentathol. Two cuts, one on each ball, then fish out the spermal cord and tie it off in two places before cutting out a small section in between. We did five all told, leaving five more for tomorrow. This procedure was much approved of by dog men, as it meant that if a dog got off the span when a bitch was on heat – and they were very good at this – then they could ‘turk away all they liked and not do any damage.’

Field party gets advice from Doc – Terry Allen

Jack Donaldson, based at Stonington Island, was out in the field with his sledge and huskies in 1969. On a radio schedule he asked to speak to the Doc.

He described the problem suffered by one of the dogs, and after some discussion we decided that the condition was rather like scurvy, due to lack of vitamin C.

I told him to give the dog fresh oranges and that would do the trick.

The subsequent stream of invective was so bad that there were complaints from Port Stanley Radio about it being broadcast over the airwaves.

There was a satisfactory result in the end, whatever the diagnosis.

Jack gave the dog his Marmite ration.

Cure. Job done!

The Complete Dog Sledging Manual – Ian Curphey

Ian spent a huge amount of time creating a record for future generations of dog sledge drivers, mainly arising from his own experiences having taken over a team with little to no handover. Ian’s document below is included with the express permission of Ian Curphey (Curf), and you can download it to read at your leisure:

12th May – Lincoln Depot Run – Bill Taylor

Curph had picked up a serious skin allergy that was still causing him problems as we approached the middle of May, but there was still another depot journey to be completed, this time to re-site Lincoln depot. I was both thrilled and proud to be told that Curf was happy for me to take over the Huns for the next run, scheduled to take place as soon as the opportunity arose. Running a 9-dog team on a full field trip was not just a dream come true; it was the fulfilment of a long-held ambition. And it started on 12th May…

“-20C, with a nasty 15-20 knot wind, but a beautiful, clear morning…and it was decided we would travel…Rod to run the Picts with Bob Davidson and me to run the Huns with Steve. We were just about ready to get away for 1145, but then there was a brief pause in the action which resulted in a major dog-fight within the Huns, started between the brothers Nasr and Hamad. Kelly then took the opportunity to duff Tuva, and when Steve waded in to prise them apart, he took a slash-bite in his leg requiring Terry to put in six stitches, thus putting Steve out of action.

My Southern Journey – Ian (“Curf”) Curphey

I am writing this as I approach my seventy-fifth year, using the journal I kept at that time. I knew then, as I know now, that the events that would unfold over the next few months would be the highlight of my life, irrespective of how much I should strive to undertake anything more memorable.

The opportunity to travel by dog sledge on a potential thousand mile journey in the relatively unknown vastness of Antarctica, was a privilege I was determined to make the best of. The tale I tell may well be of no great shakes in the big scheme of things, but to me the experiences that arose during these exciting months were to define me physically, mentally and socially. Travelling with the “Huns”, using techniques and equipment that had not significantly changed since the days of Nansen, and Amundsen, was then and remains so now, the most significant experience of my doubtless insignificant life.

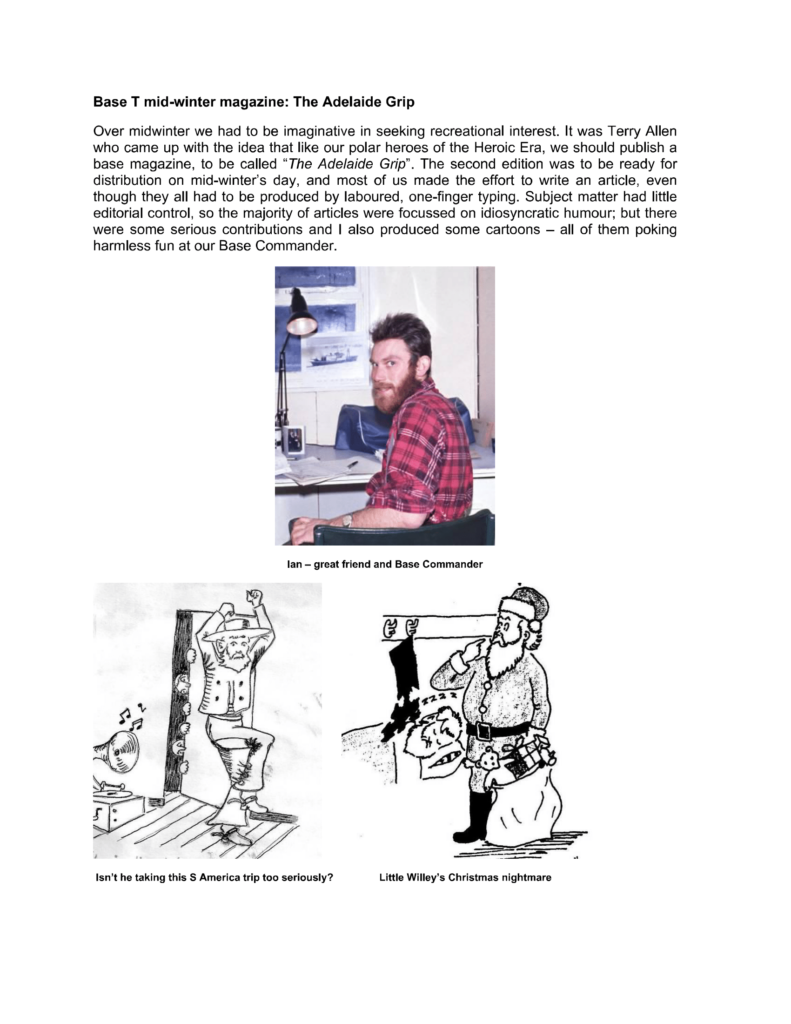

Midwinter – Bill Taylor

Midwinter Magazine – “The Adelaide Grip”

Read More “Adelaide Grip” here

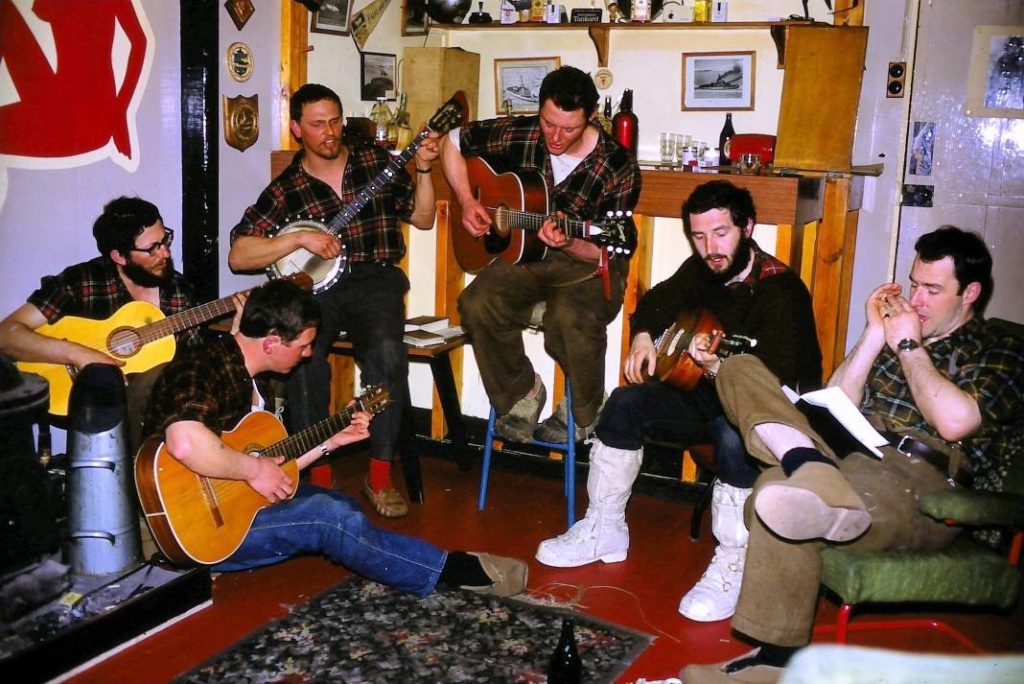

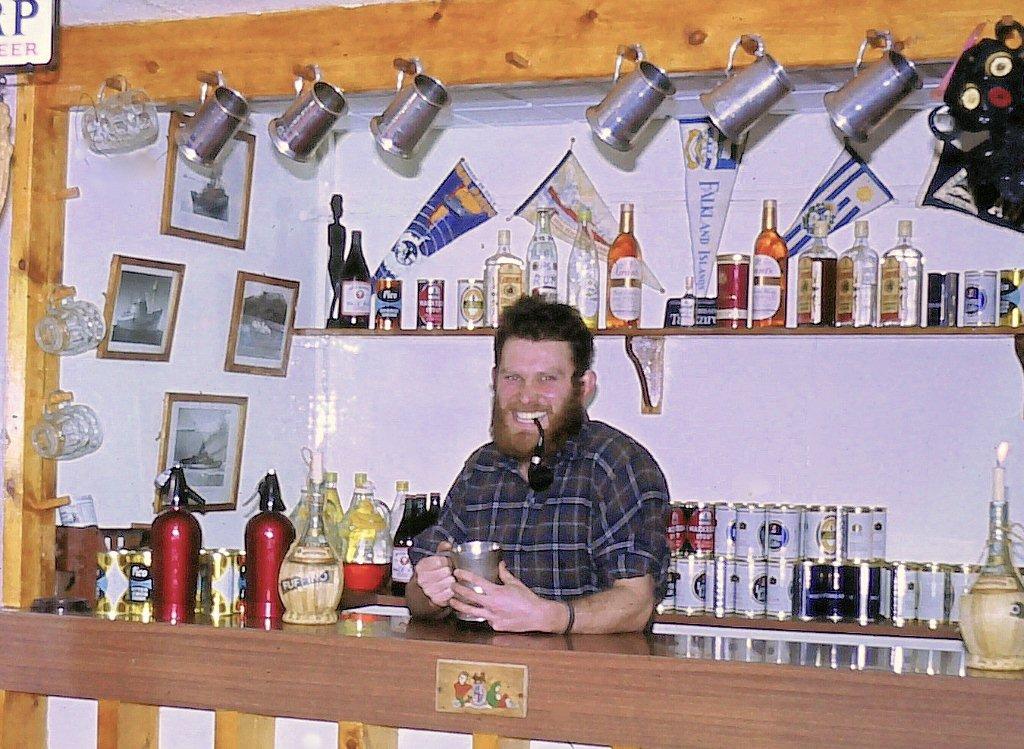

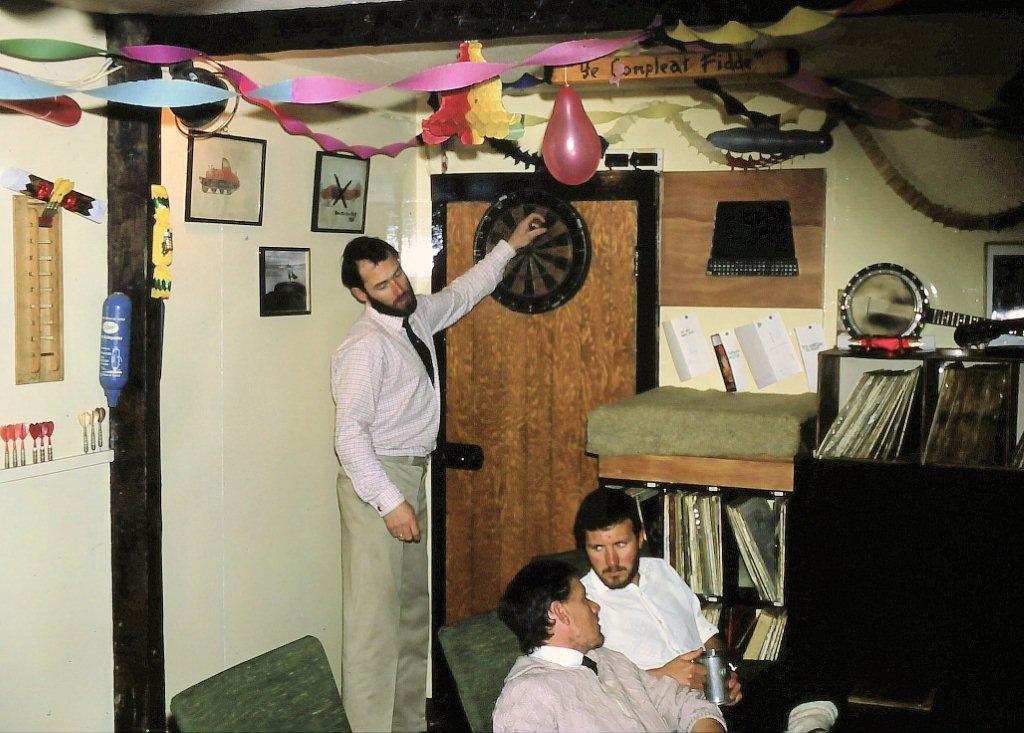

Saturday Nights – Bill Taylor

Winter Parties – Bill Taylor

Saturday night was always a special occasion. It was “fresh meat night” when the Cook took a large piece of quality-meat out of the ice cave and made a special effort to prepare a special meal, reciprocated by the rest of the base by dressing in smart clothes – in those days, most commonly including jacket-and-tie and commonly a suit. This was also the night when the base booze ration went into the bar, always supplemented by additional bottles from the private stashes of alcohol that stretched the drinking into the early hours.

Over the winter of 1969, in the true traditions of the Heroic Era, every opportunity (excuse?) to celebrate birthdays and national holidays was taken up with enthusiasm. Read on…

Met at Base T – Bill Taylor

The original Met hut at Base T was a good place for making observations in reasonable weather and on a fine day it was quite common to have “perfect” visibility that extended to the mountains of Alexander Island, over a hundred miles to the south. But the siting of the hut and instruments was not without its issues during, or shortly after, a hooly – when simply getting to the met station could be problematic, and earned rocky outcrop on which it stood the nick-name “the Eiger”.

My diary from the autumn of 1969 includes a short passage that illustrates the harsh realities of stationing the met hut on the Eiger. The context is that I had just returned to Base T from a prolonged stay at Fossil Bluff and was still feeling my way into a winter routine, considering myself a new boy on base, in spite of my previous winter on Signy. I was on met duty, and about to make a very dangerous call. ..

(Photo: Bill Taylor)

“After an evening slide show, I retired to the met hut on the Eiger with a view to staying there between the midnight and 0300 obs. But I did not bother to take my wind-proofs.

Just after midnight, the weather took a sudden turn for the worse. It was soon blowing up to 65 knots and with all the deep snow lying about, it was a full-on blizzard – the air just a mass of driving snow with almost zero visibility and with the wind-chill it was very cold. I had no choice but to stay put, intending to descend the Eiger in the morning, when I had to get the coded Met-obs to the Radio Shack for the 0900 transmission to Stanley. As time moved on, there was still no let-up in the weather, so without appropriate clothing, I floundered down the Eiger in drifts over my waste, for there was no sign of what until then had been a well-trodden path.

When I got into the main building, there was no-one about. Several windows had not been secured properly, so the kitchen, dining room and lounge were all under snow and required a full mop-out.

This was learning the hard way.”

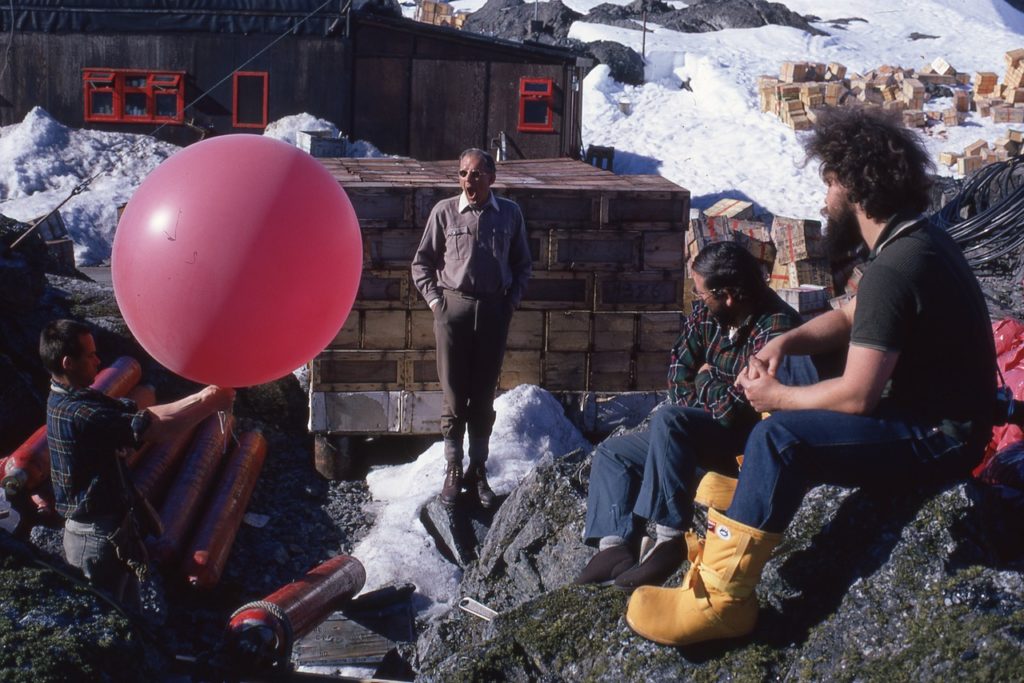

During the summer season 68-69, Base T underwent a major building programme that included a major stores building that could be accessed without venturing outside, and during the following winter, Martyn Bramwell fitted out a new met office within the new building.

There would be no more Eiger epics.

Bill Taylor – Met. Signy, 1968, Met Adelaide, 1968

The Rabble – Winter Sea Ice Sledging – Bill Taylor

With the exception of the rocks providing a stable site for the various huts making up Base T (where a glacial ramp provided easy access our airstrip on the Fuchs Ice Piedmont) the south and west coast of Adelaide presented as extended ice-cliffs, sometimes vertical and in excess of 100 feet in height.

Seen from seaward when training dogs on the sea-ice, they were very photogenic. See all….

5th July – Rabble Graduation – Bill Taylor

After managing a circumnavigation of Avian Island, the Rabble got the go-ahead to leave with the other two teams, with a departure date set for 4th July, so Steve Wormald and I now had to create a third camping unit, working against the clock. Fortunately, the weather had never agreed to let us away for 4th, and departure was put off until Saturday 5th.

The whole base was up early and breakfasted to help get us away with minimum fuss. As we loaded the 3 sledges in mid-winter darkness, Adelaide had not seen such levels of dog sledding activity for many years. The Picts and Huns, with their 9-dog teams, were carrying full loads. Read On…..

July 25th – Dion Islands – Bill Taylor

Thursday 25th turned out to be a very special day – among the very best in my term of Antarctic service. It dawned bright, clear, calm and around -23C. Steve Wormald and I were to sledge Dick Bird to the static camp on Avian Island, then bring Ian Willey back to base with a detour to the Henkes Islands, about 5 miles off-shore to the SW. This being a more serious undertaking than most of our training runs, apart from Dick and his personal bag, we loaded the sledge with an extra personal bag, a rope, skis and survival kit, and we knew that Ian would have his personal bag to be brought back with him. So much for the plan; but that is not how it turned out. The official BAS Journey Report that I subsequently wrote takes up what happened:

The Window

Base T 1969 had more than its fair share of those that thought of themselves as mountaineers and climbers, most of whom harboured ambitious plans to summit one of Adelaide Island’s alpine summits of what is now the Princess Royal Range, the big prize being Mount Gaudry, at 2565m, first climbed by a party of Royal Marines from HMS Protector in February 1963.

There were a couple of recces of the dog-sledging approaches to Gaudry via the col to Mount Barre during the Autumn depot journeys, but a proper assault never came to fruition and was not logistically viable once the Huns and Picts had left base on 5th July to support the Stonington sledging programme.

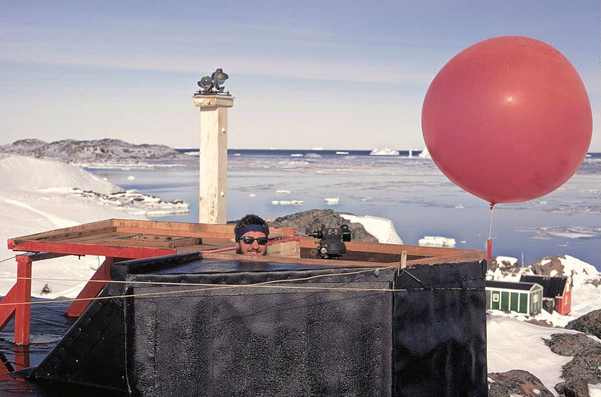

October 20th – Avian Island – Barrie Whittaker

Dick Bird, Martin Bramwell and I thought it would be a good idea to have a few days break. We arrived on Avian Island by boat early in the morning. This was not just a ‘holiday’, we had been sent to complete a survey on the the population of Adelie Penguins, that migrated here to breed every year.

Aircraft VP- FAM (Mk. 2!) – DHC-2 Turbo-Beaver

The Turbo Beaver was purchased by BAS to replace the Otter VP-FAM which met its end on the Plateau above Stonington (see story here…-to follow), and was graced with the same VP-FAM call sign.

VP-FAM was ferried from de Haviland, Downsville ON, Canada, piloted by Ferry Pilot Jim Averill together with RAF Pilot Flt. Lt. Bert Conchie, through the USA and South America to Chile. On December 7th, 1969 leaving Punta Arenas, Chile, with the Twin Otter VP-FAO piloted by Dave Rowley, VP-FAM was piloted by Bert Conchie, and Jim Averill was dropped at Anvers Island, to return to the USA, and on the same day, VP-FAM flew on to Adelaide.

December 7th – B.O. & Seal Stink – Dave Rowley

We (me, Flight Lieutenant Bert Conchie, Sergeant Dave Brown and Sergeant Ron Ward), the latter being helicopter engineers seconded from Middle Wallop Army Airbase near Salisbury, ferried the Twin Otter and Turbo Beaver aircraft from Toronto (De Havilland’s factory) through North and South America to Adelaide .

Bert Conchie and myself joined BAS together. He was the last RAF pilot to be seconded to BAS and as the first civilian commercial pilot, HQ put me in charge of the Air Unit with strict instructions that Adelaide Base Commander, Ian Willey, would determine which flights took priority, and would have the last say on whether met. conditions where safe for flight operations . After a disastrous loss of aircraft in previous seasons, HQ were keen to curb any excess of “Gung Ho” enthusiasm on the part of the Pilots . Read on…

Thoughts on Being at Adelaide as a Pilot – Dave Rowley

We used to get these parcels from home, thanks to the Bransfield and the Biscoe and this…big heavy parcel arrived for me, and ‘What could this be?’ Opened it up and it was all these curry spices and a curry kit, as I say with a book of instructions and recipes, and this became the hit of the base when I was Duty Cook, well not only when I was duty cook, Allan Wearden who was one of the cooks we had down south. I think he had a go with this, but of course we only had dehydrated and canned meat and that kind of thing, but we did used to supplement it with the odd seal steak when we took seal for the dogs! And it’s a shame not to have a choice bit of steak off the back, you know, and at it was gorgeous, and the occasional penguin.

Again, I think if I was still working for the Survey it would have been a bit, not political really to mention it to anybody in the Survey, but the occasional penguin would get the baseball bat treatment, and end up as a curry!! And so we did, yeah, we had Seal Curry and Penguin Curry and the odd Skua Curry and it was all very nice, but yes, this Curry kit went down, it went down a bomb!

Talking about seal, actually I was almost physically sick on my first seal chop, but at the end of my service with BAS I could single handed skin a seal in about quarter of an hour, very easy once you’ve got the technique and slit it down middle and get all the steaming guts out, and skin it and chop it up! And we used to feed the dogs as a matter of interest, not that I was a doggy man, I didn’t know a lot about it but we used to feed them two kilos of seal every two days in one meal, a big chunk! And that stopped them getting too fat and while they were spanned out up on the piedmont above the base, when they weren’t working. And yeah, I got pretty good at that.

Bert Conchie – BAS Air Unit Pilot – 1969 to 1974

Bert flew six seasons with BAS, starting in 1969 with Dave Rowley. Very little is written by Bert, other than the necessary Reports and logs. Here’s why…

A Very Private Person – Dave Rowley

I was as close to Flight Lieutenant Conchie as anybody could be. During five years of operating with BAS together, we shared close quarter contact, sharing accommodation on ferry flights, and the cockpit on many occasions. He knew my story from day one on our flight to Toronto in November 1969 for our Twin Otter convention course at the DeHavilland factory at Downsview Toronto

31st December – Doggy Swan Song – Bill Taylor

Ian Willey was covering the met at Fossil Bluff, but in a radio sched with Adelaide, he sanctioned a dog journey to cover as much of the Piedmont as possible and inspect a depot at Bond Nunatak that had not been visited since 1966. Curf’s BAS Journey Report states the purpose of the run as follows:

“1. As the relief driver for the Huns arrived on base early this year (i.e. Richie Hesbrook on the Twin-Otter from Anvers on 7th December) it was felt that a short field trip would be a good way to start the team handover. The depot put in at Lincoln Nunatak last April had not been seen in the last two visits, so a checking was in order.

2. According to the Depot Book, a depot still exists at Bond Nunatak and it was hoped that this could be checked as well.”

The teams to undertake the trip were to be the Huns (driven by Curf but accompanied by Richie as part of his induction as their driver for next season), and the Rabble (driven by me and reinforced by the Stonington dogs Dai, Polly and Castro). Much of the journey I describe in a letter written during a lie-up on 10th January. Read on…

The Endless Learning Curve – Dave Rowley

I have always eulogised about my wonderful paid summer holidays down south, but thought that I should balance the picture with some of the dodgier times.

Polar aviation is a pilot’s dream. No rules (other than those imposed by BAS HQ ), which we, the air unit, took lightly. We had complete freedom of the skies. After the restrictions of flying in Europe as a Professional pilot, the Antarctic was a dream, but the pot holes were there in abundance. And I attribute. no blame for the following other than my own.

A routine resupply flight to KG included 6 X 45 gallon drums of aviation fuel. It was about the third resupply trip of the day, so after loading, I left the base Fids to tie down the cargo while I went down to the base for a quick crap and cup o tea.

It had been a long day, so I was keen to get the 4 hour round trip out of the way, so that I could get back to my bunk at Base T.

After arriving back at the Twotter, all the hard working “loaders” saw me off, and I taxied down the strip and took off. As I got airborne there was a scraping noise and nose up pitch of the aircraft, which required a push forward on the control column.

I had taken off with the usual flap setting, but something told me to leave it as it was until I sorted out the problem, all under control at the moment. I called base to say that I might return, but no reply…..

Jollies with Bunny Fuchs

Landing on Icebergs – Richy Hesbrook

From my Diary:

“The Biscoe seemed to have been stuck in dense pack some way north of Adders and FAM and FAO did several ice reccies whilst ferrying stores and personnel down to T.

I think these helped to identify a suitable iceberg My diary says that on March 2nd, the Biscoe only made 12 ft. All the other mentions of aircraft flights relate to movement of personnel and stores between Anvers, Stonners and the Bluff.

Had Ted Clapp on the RT from Stanley this morning about getting this load of FIDS and Admirals etc flow down. He really didn’t say anything we didn’t already know.

Got the Beaver loaded up with the rest of the gear for Quintin and the Twin for a Bluff run but both missions were aborted due to bad weather towards the Sound. I was on the Beaver and we got to Point Charlie and still couldn’t see Alexander Is’ so we came back. The Twin did an ice recce’ for the Biscoe before landing. Burt did a hairy landing too. It was a bit bumpy coming in and we touched down a fair way down the runway. For some reason he gave the throttle a tweak and we nearly took off again. Did a really tight speedy turn to get back. Thought we were bound for the ice cliffs.

Cooking again and did a bread bake tonight.

Heard Endurance on the Goon show and also John Cole talking to Fuchs and trying to dissuade him from coming to Adelaide thought without much success. Biscoe still anchored off Cone Island

Four Fids on a Float

Fids will usually agree that the friendships they established during BAS service have a special quality that withstands the test of time. Meeting up at Marguerite Bay reunions reinforce this reality, but most of us pick up on conversations from one year to the next as if we had never been parted. So it was that in 2017, four Marguerite Bay veterans that had served together in 1969, prompted by several glasses of wine and the demolition of a bottle of Laphroaig, agreed to share one more great adventure before retiring to the dog spans in the sky. This is what happened next …

1970

Base Commander – Richy Hesbrook

| Back, E.K.P. (Kenn) | Meteorologist |

| Bell, C.M. (Mike) | Geologist |

| Bird, R.J. (Dick) | Cook |

| Chambers, R.M. (Robin) | Meteorologist |

| Hesbrook, R.S. (Richy) | BC |

| Mickleburgh, E.J. (Mick) | Meteorologist |

| Milne, A.H. (Alan) | MO, Physiologist |

| Pashley, R.C. (Rod) | GA |

| Scoffom, R.C. (Dick) | Meteorologist |

| Walker, C.R. (Twiggy) | Radio Operator |

| Walker, R.S. (Dick | DEM |

Seven Happy Years – Mike Bell (written October 2009)

I worked as a geologist on the Antarctic Peninsula, Alexander Island and South Georgia during seven years between 1968 and 1975. My mother died recently, and carefully filed amongst her papers I found some of the letters I had sent 40 years ago. Here are a few unedited snippets from those letters together with some reminiscences to try to paint a simple picture of our fun and adventure during those happy years.

First Winter Ascent – Mt. Liotard – June 2nd

First Winter ascent by Rod Pashley and Robin Chambers

Piloto Pardo’ Visit to Adelaide – Rob Campbell-Lent

(Photo: Rob-Campbell Lent)

Steve Wormald kindly brought my attention to Richard Barrett’s new story “The Falkland Islands and Dependencies Aerial Survey Expedition 1955 – 57 (FIDASE)”, that he had published in MB website (here’s a LINK ), as he thought it might be suitable for my weekend reading. He was right.

The story can greatly expand and support the basic entry in the MBW Aircraft database for CF-IJJ & CF-IGJ, the two Canadian Consolidated PBY5A Cansos flying boats operated by FIDASE. The story also contains two photographs and some interesting text detailing the use and demise of a Bell 47D helicopter, which was shipped to Deception in, and operated from, the expedition’s ship, the Oluf Sven. Seeing a Bell 47 operating from a ship in the Antarctic reminded me of some long-forgotten photos that I had of two Bell 47 helicopters visiting Base T sometime while I was there.

1971

| Apps, A.L. (Adrian) | Meteorologist |

| Back, E.K.P. (Kenn) | Meteorologist |

| Burton, P. (Paul) | Builder |

| Cook, R.J. (Robert) | Cook |

| Scoffom, R.C. (Dick) | BC, Meteorologist |

| Smith, R.P. (Ron) | Radio Operator |

| Williams, D. (David) | DEM |

Doc Mike Holmes, Mavis and Rasmus – Dave Rowley

Mavis and Rasmus are dogs that stick in my mind. As a newcomer to the land of dogs, shit buckets, seal piles, scrub outs, dog feeds of rancid seal on the dog spans, gash runs to the jetty, seal culls, Saturday scrubouts et al,

I can’ t believe how easily I took to the Fid way of life. I was never a dog lover however, and although happy to throw a putrid Seal head to the favourite on the dog spans, I was nevertheless impressed with the reverence bestowed on the beasts!

Mavis didn’t warm me to the darlings after collecting her from sledge (?), to take her to Base T to be spayed. En route, she broke loose and wrecked the Twotter cabin, leaving bloody (Read on)

Twin Otter VP-FAP Engine Change – at Fossil Bluff

Rob Campbell-Lent. BAS Air Unit Aircraft Engineer. Adelaide 1970-1972

My first awareness of the Marguerite Bay “By Fids for Fids” website was in January 2020, when I received an email from Dave Rowley (Twin-Otter Pilot, Adelaide 1969-1974) suggesting I might like to take a look at it. I had a look, enjoyed what I saw and read, but my two summer seasons there were so long ago now, and my job at the time seemed so technical and mundane in comparison to what the “Real Fids” were doing, that I could not imagine that any contribution from me would be of any interest.

However, a few months later in April I had another email from Dave saying he was about to write an account of the 1972 engine change we did on the Twin Otter VP-FAP at Fossil Bluff, and suggested it would be interesting to read an airmech’s view of the event.

So, I read the introductory “About” notes on the website encouraging contributions, and then the extract from Mike Warr’s Book ‘South of Sixty” where he explains “How It All Began for one Fid”. Mike’s account of his 1963 interview with Bill Sloman, and subsequent events sounded very similar to my own interview and induction into BAS by Bill in 1970. I had a copy of Charles Swithinbank’s “Forty Years on Ice”, and read his chapter 10 “Our Propeller Stops (with a clunk)”, to get some long-forgotten details on the story.

But it was the Stonington “Ching Stick Party” story by Ian Sykes in his book “In the Shadow of Ben Nevis” that made me finally decide to write this story.

February 22nd

The intermittent ski marks down the middle were laid down by the chopper pilot to indicate the best area and direction of landing (perfect).

The location was Hooke Point, Grahamland, 30 mins North of Base T. There then followed a 1hr 15min. seal recce of the Arrowsmith and the Fjords for John Biscoe, landing back at T, 2145. Another lovely trip by myself.

Dave Rowley in VP-FAM entertaining the Fids with a Gully Run

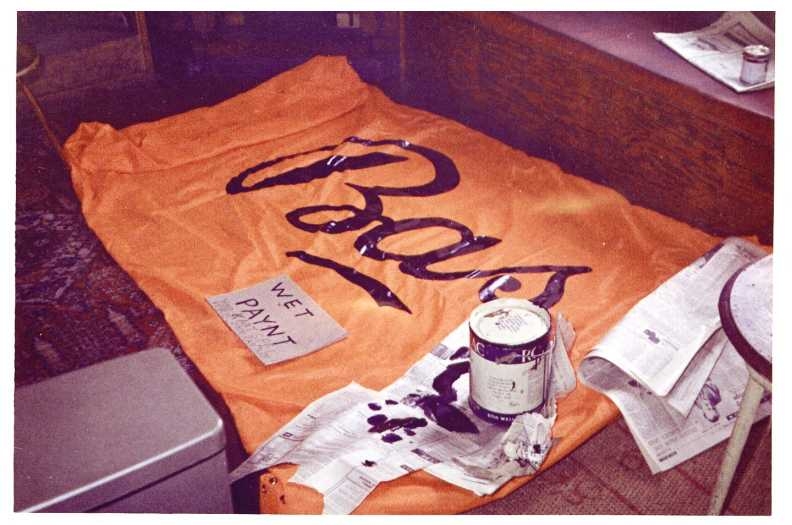

Navy Chopper Incoming – Rob Campbell-Lent

Up early to see Twiggy and Mike Bell arrive by Whirlwind on the dog spans, from Endurance. They landed the helicopter on the beach in Boat Bay and said it was ok, but would like a wind sock! I spent the rest of the day making one and it on some scaffolding on the pup pen by Stephenson House. Mike and Twiggy brought back 1 gallon of French Brandy for £2, and 6 bottles of wine at 2 shillings each from the Endurance.

1972

Base Commander – Frank Lines

| James, R.V. (Ronald) | Builder |

| Jozefiak, M. (Mike) | Radio Operator |

| Kynaston, C.M. (Colin) | Meteorologist |

| Lines, F.E. (Frank) | BC, DEM |

| Merson, J.M. (James) | Meteorologist |

| Vallance, S. (Steve) | MO, Physiologist |

| Wearden, A.J. (Al) | Cook |

| Wilkins, R.W H. (Roger) | Meteorologist |

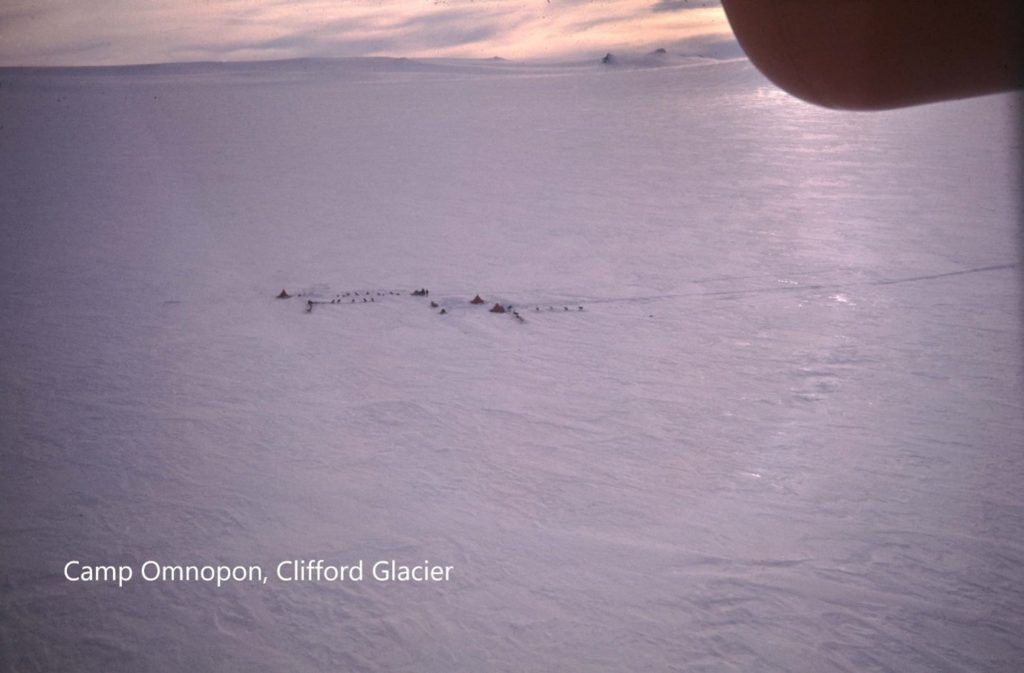

Rock Hudson’s Evacuation – Steve Vallance

On the morning Sunday October 1st 1972 Graham (Genghis) Wright contacted Base T concerning John (Rock) Hudson. For 2 days he had been suffering increasing symptoms and signs of a small bowel obstruction. He had severe abdominal pain not helped by 100mg of oral pethidine. Genghis felt, correctly, that an Omnopon injection was needed but wanted medical approval. Rock had suffered intermittent stomach pains since his appendicectomy before leaving the UK.

A Tale of Rasmus – Roger Wilkins

Those of us who remember Marguerite Bay some 50 years ago may be classified by the younger FIDS as a bunch of Old Farts, reminiscing about a mythical, bygone, Golden Age, when men and dogs faced the Rugged South with some 2000km between us and the Edge of Civilization (aka Stanley). There is at least a little truth to this – remember Steve Vallance’s recounting of the evacuation of Rocky Hudson – but what you are about to read is not a tale of the normal kind, for this is a tale of a husky Old Fart, a Tale of Rasmus.

Those who remember him may also remember that, in a moment of compassion, to spare Rasmus from the lead tablet that would have dispatched him to the Great Span in the Sky, given his age and inability to continue as a useful work dog, Bert Conchie smuggled him onto his plane and flew him down to Fossil Bluff, for a peaceful retirement amongst the glaciologists.

1973

Base Commander – Jim Roberts

| Andrews, C.J.H. (Chris) | MO, Physiologist |

| Avery, K.F. (Keith) | Meteorologist |

| Barker, R.C. (Roger) | Cook |

| Jozefiak, M. (Mike) | Radio Operator |

| Ramage, G.H.P. (Gordon) | Tractor Mechanic |

| Roberts, K.J. (Jim) | BC |

| Taylor, I.G. (Ian) | Meteorologist |

| Wilkins, R.W.H. (Roger) | Meteorologist |

The Rabble – Roger Wilkins

We have probably all heard of transitioning to retirement. In fact, in Australia, there is a separate set of rules for those who want to Transition to Retirement using access to their Superannuation whilst still working Part Time. This need for a transition is, of course, a need largely imagined by those still working. Rather as a person offered water after being lost in a desert or someone offered food after a period of starvation, apparently the excesses of retirement are too intense to be gorged all at once. Strangely, for most of us the reality of the freedom and joy of no longer working is easy to handle. As we are likely to say, how did we ever fit work in?

Most huskies, on the other hand, had only a brief transition to retirement, which lasted for approximately the time it took to load and cock a Webley service revolver, before they transitioned further to the Great Span in the Sky. A few experienced full retirement – Rasmus at Fossil Bluff comes to mind – but the semi-retired state was rare, I think, except for The Rabble at Adelaide. I am not sure of the history of this team but I do know that they gave great enjoyment to those of us privileged to work with them in the early ‘70’s and I do believe they enjoyed the experience as much as we did.

The Uti-Lurker – Gordon Ramage

As many of you already know the “Uti-Lurker” was the mainstay of the hard work that was required in maintaining the constant supply of Men, Materials and Fuel, whether it was unloading the ships workboats, or restocking the aircraft for onward support of field parties all over Marguerite Bay and beyond.

In Awe of Fids – Captain Dave Rowley

Since leaving the Survey in April 1974, I have always wondered how the lads on base and in the field viewed the Pilots. I stipulate Pilots , because they were usually RAF officers, where the mechanics were NCO’s .

When I arrived at Adelaide (Base T) for the first time , it was a moment of revelation. I imagined beautiful clean odourless, pure, pristine air, but the induction course at Cambridge didn’t include smells!

After a shower and breakfast in the Cabo De Hornos Hotel in Punta Arenas, Chile, eighteen hours previously, we touched down at Base T. I have previously written about my first couple of days on base impressions, and remember a great welcome. From my point of view (as a 32 year old) everybody looked very young, despite the copious facial hair (in some cases bum fluff! ).

My day of revelation arrived on the evening of 10th Dec. 1969 . One FID flown to Anvers 2115 to 2315 (who was he?), return Adelaide 2330 to 0115 GMT, with 2000 kilos of freight. No ferry tanks, no air traffic control, complete freedom to dive down and look around, or go up and look at the Peninsula bathed in the midnight sun. How many pilots have had such freedom?

The following day was awe-inspiring:

L to R: Ali Skinner, Steve Wormald, Captain Dave Rowley , Brian Hill, Gwynn Davies, Dick Scoffam (Photo: Rod Pashley)

What a day, dingle clear and in awe of shaking hands with instant friends, standing in this paradise of tranquility (when dingle!), with a mug of tea.

But how did FIDS think of us?

(If Fids care to comment (good or bad!), send by email to [email protected] and we’ll add some here (the good ones!) and pass the bad ones on to Dave!)

And finally, can anyone remember being the Fids helping lay the Davis Top Depot in 1973/74 Summer season?

Here’s the answer:

In January/February 1973 (can’t remember which as I didn’t keep a detailed diary when on base) I flew with Dave to Davies Top, probably on a depot laying trip. As he was going there anyway, I took the chance to do a gravity measurement between Stonington and Davies Top to strengthen the network measurements.

I can’t remember who else was on the flight, and strangely I took no photos on the way out. I have a few fine scenery shots taken on the way home to Stonners.

(Malcolm McArthur, Geophysicist, Stonington 1971 & 1972) (see also “The Ptolomy Incident”, Stonington 1972/3)

In Awe of Army Engineers

They are always in the background, but these guys kept the aircraft flying, and in the six or seven years of our service, everything was done in the open. In the Deception years they had a hanger, and of course Rothera has the ultimate.

Can you imagine changing a component on the engine or recesses of the fuselage in often gloomy none flying days, probably windy and awfully cold.

Ron Ward told me that while changing a component on one of the engines that his screw drivers kept breaking. He eventually found one that he bought in a DIY shop in Toronto that did the job!

And then, there is the epic engine change at KG. What brilliant technicians they were. As a Junior Technician in the RAF, I cannot ever remember any of us being trained up to the standards of those chaps. Nothing gave them doubt or “not doable”.

Those last few years of Base T were unique, and I am aware that all the air unit between 1969 and 75 know it.

Dave Rowley – BAS Air Unit, Adelaide, Pilot – 1969-1975

Ice Depth Sounding Program

In this grip, Dr. Charles Swithinbank was probably recovering from flying me into the ground (almost literally) after one of our usual six hour ice depth sounding runs at 30 feet contour flying over the Peninsula. He was a brilliant navigator though, all I had to do was fly and follow his directions.

If we had come to grief, I wouldn’t have had a clue where we were!

Dave Rowley, Pilot – Adelaide Air Unit – 1969 to 1974

The Theron Mountains Trip – February 1974

Me and Bert did the first flights to Halley Bay and back from Adelaide in order to pick up Sir Vivian (“Bunny”) in his last year as Director, and Derek Gipps, for a tour of the Peninsula bases.

During our stay at Halley, I flew Bunny, and Captain Tom Woodfield up to the Theron Mountains and beyond. We were only a breath from the Pole, but Bunny decided that it wouldn’t be etiquette to ‘drop’ in unannounced, so we headed North with a sinking heart .

The next day, Capt. Woodfield invited me and Bert to join them for a trip to Shackleton Base***. I leaped at it, but Bert declined, he told me that he wanted to live the life of base. Typical of the person.

*** – Shackleton Base was established on the Weddell Sea Coast, as one end of the Trans-Antarctic Expedition by Vivian Fuchs, with Scott Base being established on the Ross Sea by Sir Edmund Hilary. You can read more HERE

1974

Base Commander – Kevin Roberts

| Almond, A.A.J. (Adrian) | Geophysicist |

| Bury, I.T. (Ian) | Cook |

| Carter, J.F. (John) | DEM |

| Dikstra, B.J. (Barry) | Geophysicist |

| Harris, M.R. (Mike) | Radio Operator |

| Henderson, I.E. (Ian) | GA |

| Hobbs, S.A. (Simon) | GA |

| Jackman, C.W. (Clive) | Meteorologist |

| Killick, J.S. (John) | Meteorologist |

| MacLeod, A.D. (David) | Medical Officer |

| Roberts, K.J. (Kevin) | BC |

| Taylor, I.G. (Ian) | Meteorologist |

| Wroe, S.C. (Steve) | Builder |

Oh Well, Back to the Fid-built Version

Because of the large amount of aviation fuel incoming to Adelaide, the use of the Muskeg fitted with a Tico crane, which had been stored at South Georgia all winter, was requested and approved by London H.Q. This vehicle was intended to serve the purpose of sitting on the jetty to offload the Avtur drums from the scow, thus releasing the “Uti” Muskeg for work on the Piedmont enabling fuel to be moved direct to the airstrip having been lifted to the top of the ramp.

(Photo: Rob Collister, 1971)

In addition, the crane on the “Uti” was a Fid-built version, albeit excellent. It had been pointed out that the survey were placing the success or failure of this year’s field programme, and also the airborne radio echo sounding programme, entirely on this home made crane.

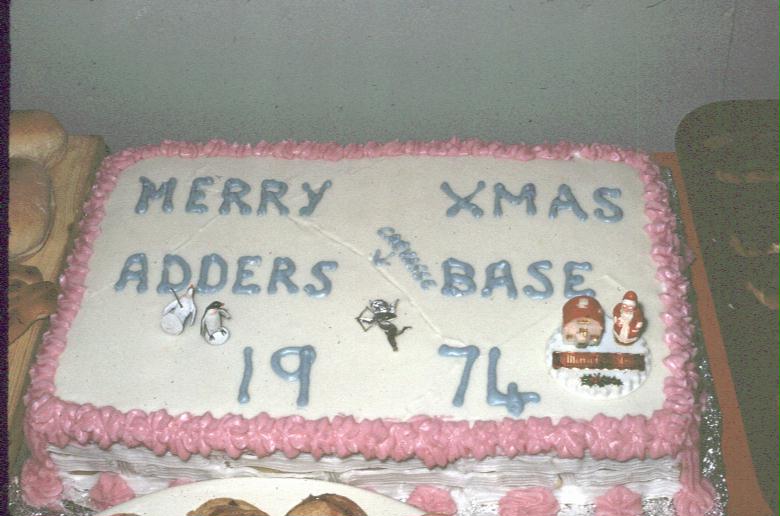

Christmas Dinner (Photos: Steve Wroe)

1975

Base Commander – Brian Sheldon

| Bravington, D.N. (Dave) | DM |

| Davies, R.A. (Rob) | Tractor Mechanic |

| Harris, M.R. (Mike) | Radio Operator |

| Henderson, I.E. (Ian) | GA |

| Holden, G.A. (Dog) | GA |

| Jackman, C.W. (Clive) | Meteorologist, Physicist |

| Knott, C.E. (Chris) | GA |

| Lipscomb, A. (Tony) | Medical Officer |

| McManus, A.J. (Alan) | Cook |

| Sheldon, E.B. (Brian) | BC |

1976

Base Commander – Rob Davies

| Airey, R.F. (Rick) | Radio Operator |

| Atkinson, Richard (Rick) | GA |

| Ball, D.A. (David) | Cook |

| Chantrey, M.F. (Mike) | GA |

| Davies, R.A. (Rob) | BC, Mechanic |

| Hadley, M.D.M (Don) | Medical Officer |

| Park, W. G. (William) | DM |

| Phillips, T.R. (Trevor) | GA |

| Salmon, T.W. (Tony) | Tractor Mechanic |

My First Seal Feed – Rick Atkinson

I arrived at Adelaide at the tender age of 21. I was probably a little too arrogant for some people’s liking and definitely very vulnerable to the merciless banter and leg-pulling skilfully practised by the “Fids” in residence there.

Ian Henderson, a self-assured, lively character from the wilds of Northumberland suggested that I help him feed the dogs. Ian had spent the previous two and a half years sledging with the dogs and obviously considered himself to be an old hand. I had happened to mention to him that I was keen to do some dog sledging and probably implied I thought there would be nothing to mastering the techniques required.

Feeding the dogs was apparently a messy business and so we dressed up in Ventile outer garments that were used for no other purpose; they were so impregnated with rancid seal blubber they would have competed with the best oilskins. Once dressed we collected the hamesses and set off for the dog spans where the sledge we used for seal carcasses had become half-buried in drifted snow.

The dogs were frantically running round in circles on their chains by this time, knowing full well it was feeding time. Ian showed me how to lay out the traces and prepare the sledge, casually suggesting that we would need nine dogs to pull the fully loaded sledge back up from the seal pile. This seemed a little excessive, I thought. We quickly harnessed up the dogs and then clipped them into their respective places on the gang line. They were facing the ice ramp towards the air strip, and, above the noise of the dogs, Ian shouted to “run the dogs up it before turning them so as to take the wind out of their sails before coming down to base.” He told me the commands, then released the anchor and the dogs took off at full pelt up the hill, with me holding on for dear life.

Suddenly, to my horror, lead dog “Sue” changed her mind about where she wanted to go and turned the team towards base. Our speed increased as we started to descend. The small braking device on the back of the sledge proved totally ineffective on the hard icy surface of the ramp. I began screaming at the dogs, begging them to slow down. This only seemed to make them go faster. Unfortunately for me they also veered one hundred yards or so left of the course we had walked up. Ahead of me now, instead of the gradual slope of the ramp, there was an ice cliff dropping some ten feet to the sea shore below. The dogs were going too fast to do anything except jump off the edge. They landed surprisingly gracefully. The same could not be said for me or the sledge as we hit the stones below with an almighty crash. Amazingly I managed to hold on to the sledge as the dogs continued running as if nothing had happened. Ahead of us, strategically placed, lay numerous empty oil drums. The dogs negotiated a course between them; the sledge however bounced off one to the next, creating a noise similar to war drums in darkest Africa.

Emerging on the other side of the drums the cause of all the urgency was plain to see. The seal pile! A considerable number of partially decomposed seal carcasses lay piled up between the walls of a rocky gully. Once amongst the seals the dogs had no desire to leave but my troubles were far from over. As is unfortunately the way with huskies, they became most uncivilised when it came to sharing food and began to fight. By the time I had gathered my wits together, all nine dogs were engaged in deadly combat. I lay into the dogs in a futile attempt to disentangle them, only to find myself becoming plastered in putrid seal flesh.

A feeling of frustration and embarrassment overwhelmed me as I noticed that most of the base members had assembled above me on either side of the gully. They were all having a good laugh at my expense. I had been well and truly set up. They all knew the outcome of my attempts to feed the dogs was likely to produce some first class entertainment and were occupying the ringside seats. My ego had been totally deflated.

Rick Atkinson, GA – Adelaide 1976, Rothera, 1977

Wind and Rain – Rick Atkinson

We had spent 2 days pinned down by a storm camped on Horseshoe Island. On the second night one of the dog spans came adrift with 5 dogs attached to it. They had spent the night in combat and had become utterly entangled. Tom, one of the less dominant dogs, had taken the brunt of it but all five were very much the worse for wear. There must have been a hell of a noise but the wind was so strong that we heard nothing. The first that we knew of the goings on was being furtively greeted by Tiger who had managed to free himself and he sheepishly approached us as we walked to the sledges in the morning.

None of the dogs appeared seriously injured though they were obviously sore and bruised. The weather had enormously improved and, just as were about to leave, Penny, a particularly nervous bitch from the Huns, managed to slip her harness and refused to be caught. After wasting a precious hour of travelling time trying to entice her back we gave up and set off without her. As expected she followed, trailing behind at a distance but as the dogs slowed down to a steady trot she annoyingly started to prance alongside Sue, my leader.

Treading on Thin Ice – Rick Atkinson

About seven miles out to sea from Adelaide base there was a cluster of rocky skerries known to us as the Dion Islands where the only Emperor Penguins to be nesting on the Antarctic Peninsula are to be found I was keen to see the penguins but the sea was somewhat reluctant to freeze sufficiently to permit our crossing to the islands. Finally about three weeks after mid-winters day the ice seemed to have frozen all the way across. Without mentioning our plan to any other base member for fear of being warmed against such a reckless notion two us departed from base with two dog teams intending secretly to visit the islands. We made good progress as we headed out, the weather was fine and there was no wind. The sea ice seemed solid and had a covering of an inch or so of soft new snow and the sledges were running splendidly.

Closing Base T, Adelaide Island 1977

The story of how Base T, Adelaide island came to be opened in 1961 has already been told and of course the base was originally supposed to have been located at what became Rothera Point.

So, it seemed natural that when Rothera Base was finally established in the mid-1970s that Base T would close. In any case, the ski-way/airstrip and ramp to access it were deteriorating, as has been well documented.

I had already spent a winter at the then Adelaide Base in 1975. This was originally was supposed to have been my second winter at Stonington Island but since that base was closed at the end of the 1974/1975 season, those few of us due for a second year were transferred, with our dog teams (or what was left of them!) to Adelaide Island.

In 1976 I was back in the UK and preparing for a winter at Halley and a summer season in the Shackleton Mountains. However, late in the day, plans were changed, and I was asked to go to Rothera as Base Commander for winter 1977. Before that was to happen, I was assigned the task of closing Base T.

Some items and equipment had been taken overland to Rothera Point during the previous winter, including an eventful trip for the International Harvester tractor, “Mary” (see Alec Hurley’s account in Rothera Section). There were still however vast quantities of contents and material needing to be packed and catalogued, ready for shipping. An accurate list of all cargo was as necessary for the ship’s manifest whether its destination was a few miles round to Rothera Point or to other BAS bases or even back to the U.K!