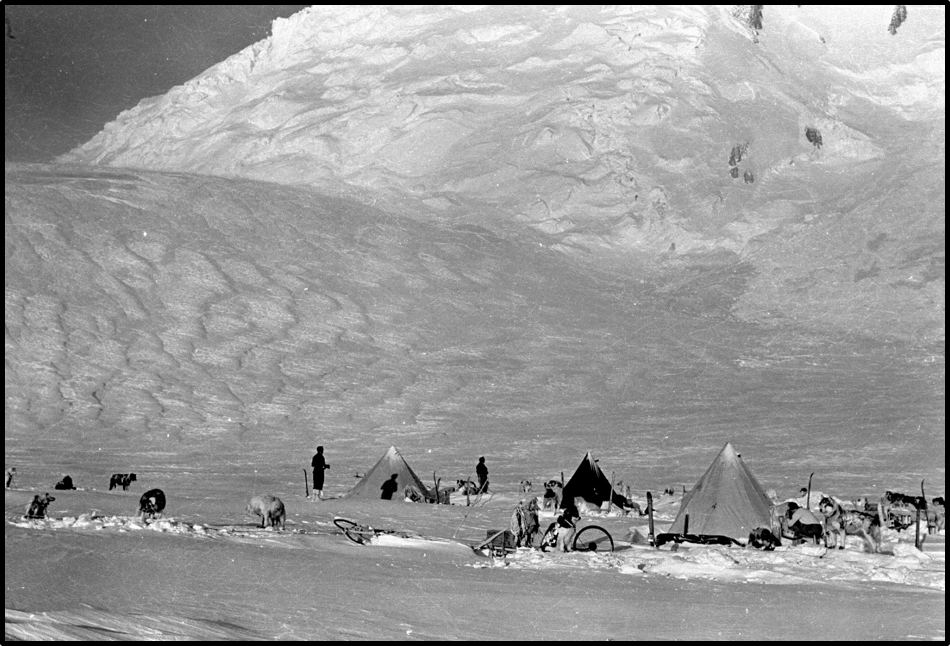

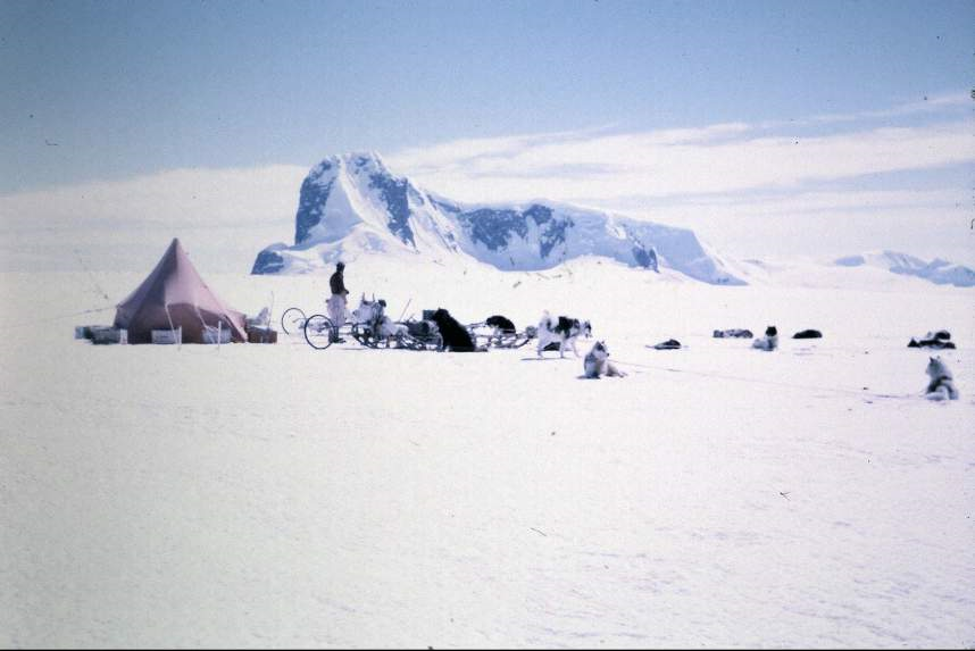

Header Photo: The Most Beautiful Place on Earth (Photo: Keith Holmes)

Marguerite Bay and Stonington Island – Jonathan Walton

British Graham Land Expedition – 1934-37

The story of BGLE is fully recounted in John Rymill’s book “Southern Lights” (recently republished by UKAHT). It is very much a bridge between the “Heroic” era of Antarctic exploration, up to about 1922 and the modern age (from 1939 onwards).

BGLE was both an exploratory and a scientific expedition and was the first expedition to make use of modern communication, having radio communication with the rest of the world throughout its 2 year duration. It set a pattern of living and working in the Antarctic which influenced all the expeditions that followed, especially Operation Tabarin and FIDS. Indeed, many aspects of their field work are still followed today by BAS, more than 80 years after BGLE returned home.

Transportation to the Antarctic was in an elderly three-masted sailing ship christened the Penola, which had an unreliable auxiliary engine. The expedition spent 2 winters in Antarctica. The first was in the Argentine Islands, further North on the West coast of the Peninsula.

When they realised it was impractical to dismantle this hut and re-erect it for their second winter they quietly nipped up to the abandoned whaling station in Deception Island and “borrowed” some timber that had been left in neat piles on the foreshore. They then sailed South and built the base for their second winter in Marguerite Bay – on the Debenham Islands, about 5 miles North of Stonington Island.

USASE – Stonington Island “US East Base” – 1939-41

Tiny Stonington Island has played an important role in the exploration of the Antarctic Peninsula since the early 1940s. It was named after the small port of Stonington in Connecticut, the home of Nathaniel Palmer who was a very influential early Antarctic sealing captain in the early 1820s.

In 1939, America built “East Base” on the island which was occupied until early 1941 and was commanded by Captain Richard Black. This was the sister base of “West Base” on the Ross Ice Shelf, commanded by Admiral Richard E Byrd. Both Bases were established as a part of the United States Antarctic Service Expedition.

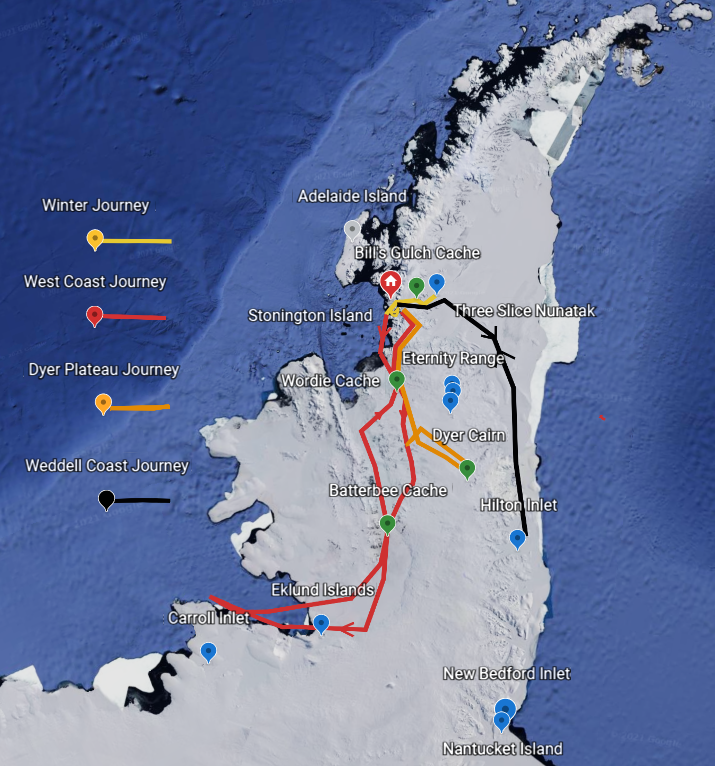

They carried out a lot of interesting work and two of their number. Finn Ronne and Carl Eklund achieved a massive unsupported sledging journey across Marguerite Bay’s sea-ice to George VI Sound’s ice shelf, discovered a few years earlier by BGLE. They also recce’d a route inland from their base and across to the East Coast of the peninsula. They sledged the whole length of this Ice shelf as far as what is now known ad “Eklund Island” at nearly 73deg South. They were the first to prove conclusively that Alexander I land, named after a Russian Czar by Thaddeus Von Bellingshausen in the early 1820’s should be correctly named Alexander Island.

The base was abandoned in a hurry in 1941. The firsts FIDs appeared in this area in February 1946 having been given firm instructions to build another building on this tiny island. While it seemed crazy to have two bases only a few hundred yards apart, Stonington had the unique distinction of being the only location along this stretch of coast from which one could travel straight on to the mainland without requiring any sea ice. When FIDs arrived it was clear that East base had been “gone over” by various visitors since it had been abandoned – they had left doors open and generally created quite a mess. This meant that East base in January 1946 was full of snow and ice and totally uninhabitable.

See the full story of USASE HERE

In addition, the story “The Dogs of East Base”, sent in by Neil Marsden, relates in detail the sad story of the USASE dogs at Stonington in 1941. Neil was intrigued by a paragraph in Jenny Darlington’s book, “My Antarctic Honeymoon” plus a brief sentence in Kevin Walton’s book “Two Years in the Antarctic” relating to the dogs of the USASE in 1941.

Further research unearthed the comprehensive report by Joan Bryner. This is quite a long report and worth persevering with; however the evacuation of Stonington begins on page 37 and details the fate of the dogs – Read on HERE“

FIDS – Stonington – “Base E” – Winter 1946 and 1947

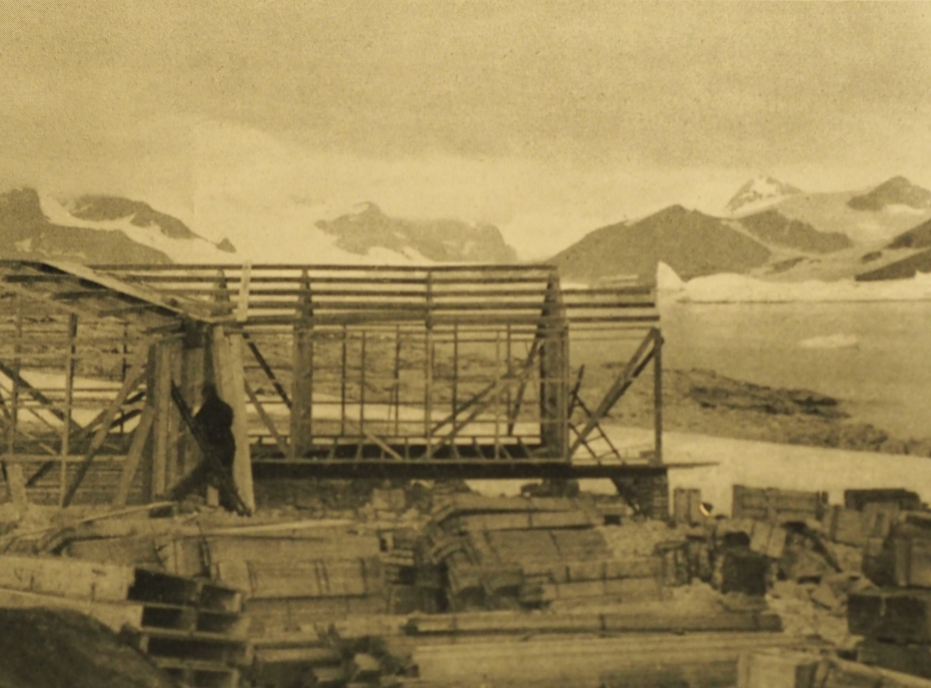

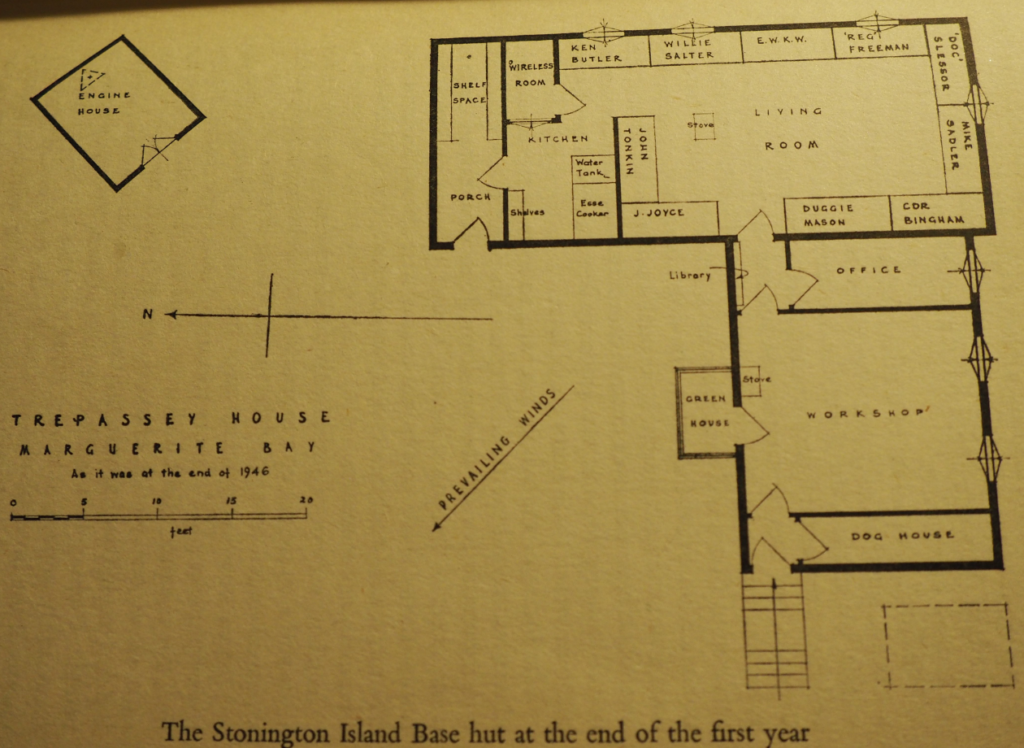

The ship Trepassey arrived at Stonington Island on 22nd February 1946. The small vessel was grossly overloaded and in due course everything was delivered ashore. First task was to de-ice and clean up the American huts so that all the FIDs could shelter there while they were building their own base. At this stage it was still “Operation Tabarin”.

This temporary occupation meant that Trepassey could be released for work elsewhere as soon as possible – it also meant that building work could progress despite the vagaries of wind and weather. It was sited about 200 yards from the American buildings and “moving-in” day was in late March. They continued to make good use of the spacious American building as a sledge building and tent repair workshop making sure it was kept in good order.

Sadly in early 1947 warships belonging to both Chile and Argentina visited base E, the crews were let ashore and “The American huts were reduced to a state far worse than that in which we had found them a year before” (Walton, Two years in the Antarctic).

Ronne Antarctic Expedition – Winter 1947

This expedition arrived at Stonington in March 1947, expecting to occupy East Base. This group included 2 women, married to the leader and deputy leader respectively, who were to be the first females to spend a winter in Antarctica. Their Leader Finn Ronne refused to believe that it was not the British that had created havoc in the base and life became rather difficult with a “no fraternization” order applied by Ronne. When he visited the British hut, he stated that their base was so clean and tidy that it was clear that they hadn’t lived in it for the last year but had been occupying the East Base – an observation that the FIDs accepted as a great compliment. However, harmony resumed and the Americans with their considerable air support and the FIDs with their well established overland travel capability worked together very effectively for the year.

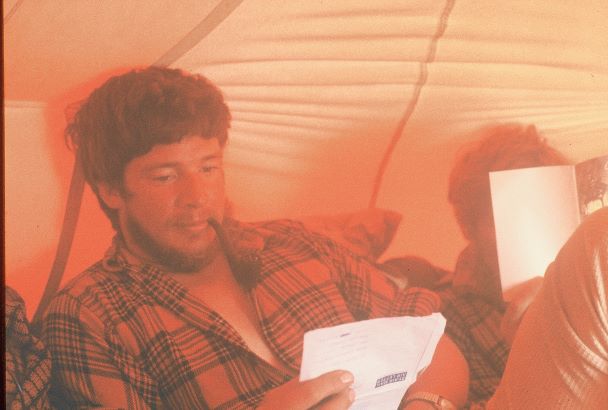

US – UK Cooperation – Picture Post Magazine, 1948 – Kevin Walton

“The most difficult part of one’s return from Antarctica is to convince people that life down South, with its very generous allowance of cold and snow, is not now full of the hardship and discomfort connected so rightly with such names as Scott and Shackleton. And the purpose of this article is to pay tribute to men of all nations who were there before us, whose carefully recorded experience has laid the foundations of modern Polar life.

Two and a half years of life cannot be compressed into a few paragraphs, so I intend to try and answer several questions typical of many that I have been asked. We were eleven men in a base, in a hut that we built ourselves in the Antarctic, and the answers can come from there. How was it, people say, that the cold and rigour of the climate did not affect you as much as it did others in days gone by?

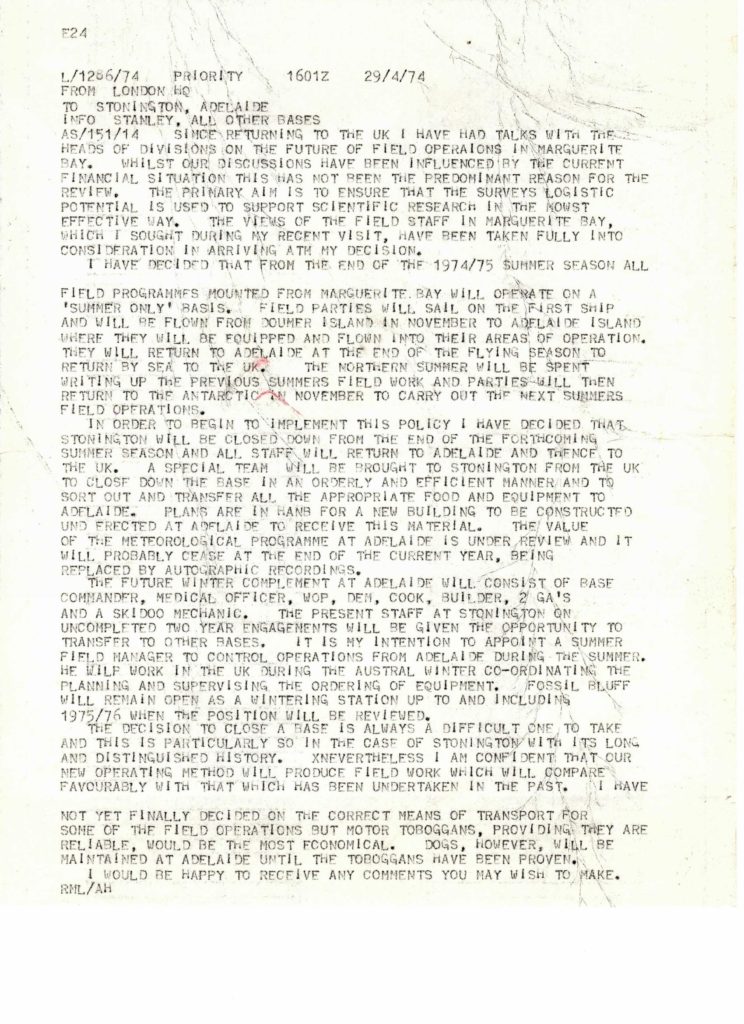

Stonington – FIDS – Winters 1948, 1949

These 2 winters were under the leadership of Vivian Fuchs, the new Director of FIDS. Unfortunately the sea ice meant that in 1948 it was impossible for the relief ship to reach the base so the FIDs were stuck for an additional winter – this meant that for some of them they were in the Antarctic for 3 successive winters. Because of the vagaries of the sea ice and the uncertainty of being able to relieve the base each year it was considered inadvisable to keep Stonington open any longer so in 1949 the base was closed.

1961: Base re-opens

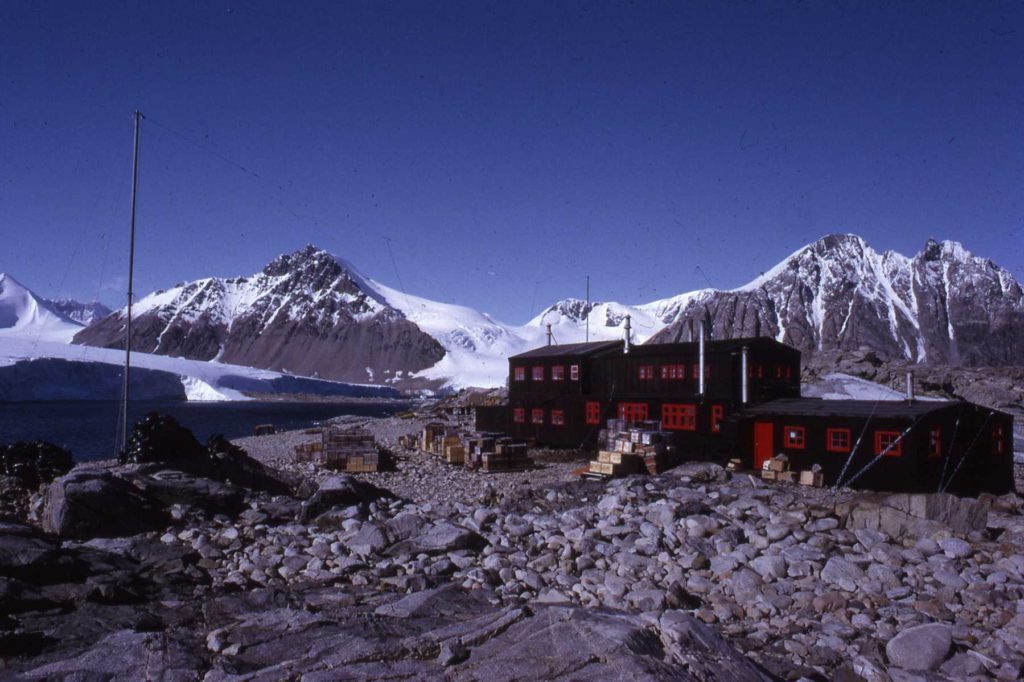

The station was re-sited when a new main hut was erected in March 1961. The new hut was the first two-storey building to be erected by FIDS. Two single-storey extensions were added, one in 1965, and another begun on 27 Jan 1972. Buildings from East Base were also used as workshops and stores. These were known as Passion Flower Hotel, Jenny’s Roost and Finn Ronne. The Base hut was cleaned up and repaired in 1992, and apparently the UKAHT counted the paperbacks there!!

Historic sites

A protected area on the island consists of the buildings and artifacts at East Base (with their immediate environs) that were erected and used during the two US wintering expeditions. The size of the area is about 1,100 yards (1,000 m)north-south, from the beach to Northeast Glacier adjacent to Back Bay, and 550 yards (500 m) east-west. It has been designated a Historic Site or Monument (HSM 55) following a proposal by the US to the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM). Base E is also considered to be of historical importance in relating to both the early period of exploration and the later BAS history of the 1960s and 1970s, and it has been similarly designated a Historic Site or Monument (HSM 64) following a proposal by the United Kingdom to the ATCM.

1960s and 1970s

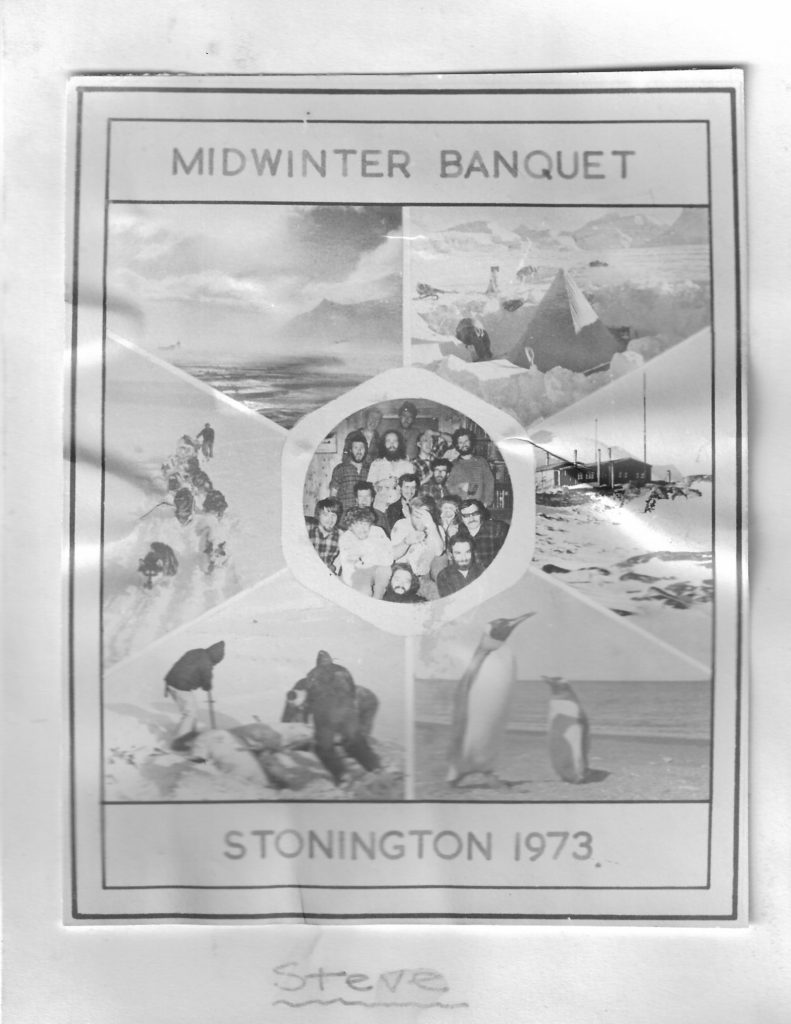

The Story of Sodabread

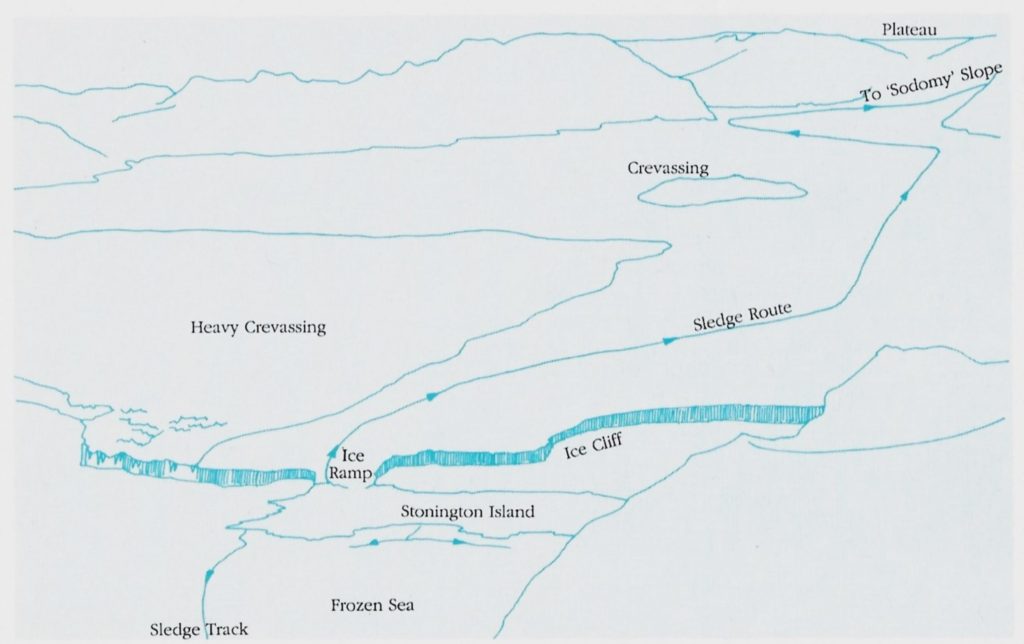

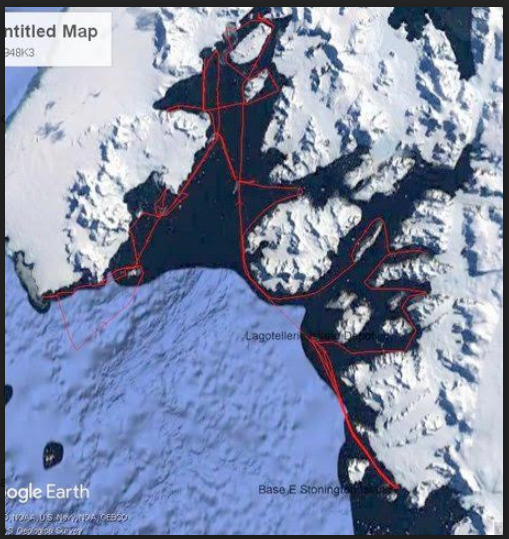

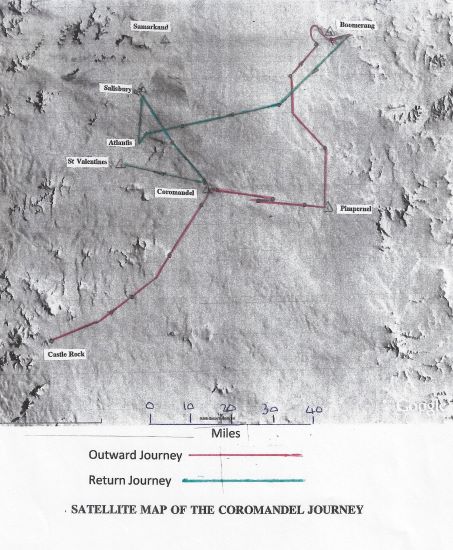

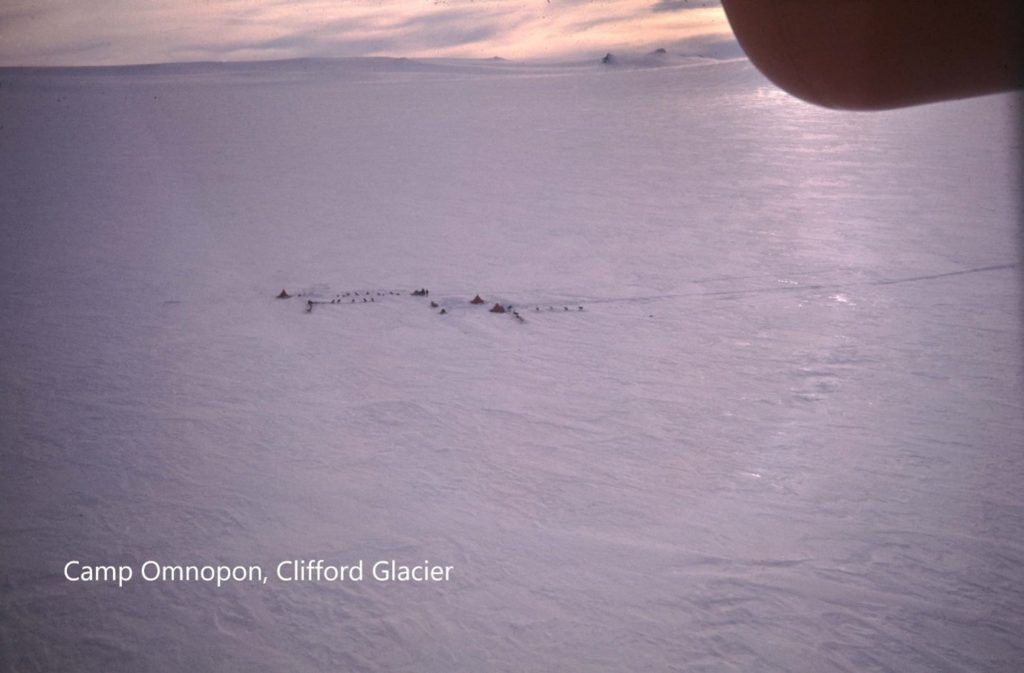

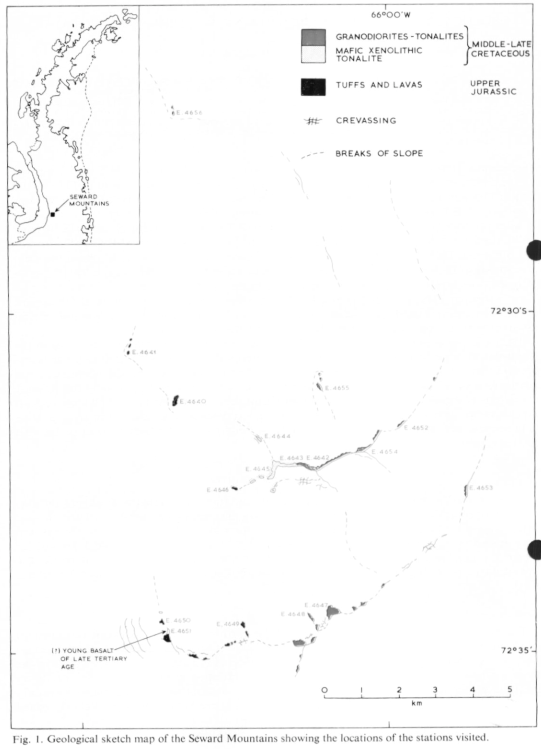

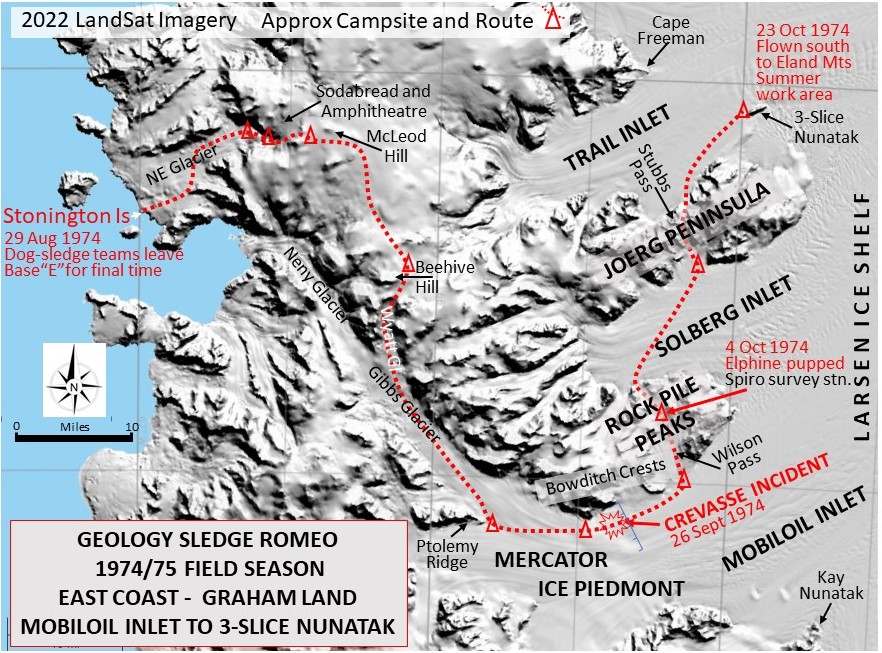

Stonington during the 1960s and 1970s was the base for exploration to the South, and two routes existed to reach the geological, geophysical and topographic survey areas – over the sea ice, or via the Antarctic Plateau.

The route to the Plateau from Stonington was via the Northeast Glacier, and up the glacier icefall commonly known as Sodabread.

In Sir Viv’s book (“Of Ice and Men”) he wrote that Sodabread Slope was a name used by BGLE in 1946, substituted from “Sodomy Slope”, and that Sodomy Slope was a pseudonym for “an even ruder name”.

However, Keith Holmes (Stonington, 1965 and 1966) writes:

For some reason, Sodabread remains an unofficial name, despite its huge significance in the exploration of the Antarctic Peninsula, but, in his definitive account of Antarctic Place-names,[1] Geoffrey Hattersley-Smith did quote Kevin Walton’s retrospective use[2] of Sodabread Slope. Dick Butson also used it the published version of his 1947 diary[3]. Sodabread, (and Soda Slope[4]) were, in fact, euphemisms for the colloquial expression Sodomy Slope,[5],[6]. Read on….

And, Roger Scott (Stonington, 1973 and 1974) writes:

The name always seemed a bit odd for what is a very steep slope for access to the plateau. What has a steep snow slope to do with bread made without yeast?

As far as I can remember I was told the ‘potential’ origin of the name from Kevin Walton on Bingham’s BGLE in the winter of 1936. I say ‘potential’ as I cannot think of anyone else of my acquaintance who would have had any knowledge of the slope and its name. I used to visit Kevin regularly during the time he was putting together the words and photographs for “Dogs and Men”.

Winters:

1946

| Bingham, E.W. (Ted) | Base Commander |

| Freeman, R.L. (Reg) | Surveyor |

| Joyce, J.R.F. (John) | Geologist |

| Mason, D.P. (Douglas) | Surveyor |

| Pierce-Butler, K.S. (Ken) | WOM |

| Sadler, W.M. (Mike) | GA |

| Salter, W. de C. (Willoughby) | Meteorologist |

| Slessor, R.S. (Stewart) | Medical Officer |

| Tonkin, J.E. (John) | GA |

| Walton, E.W.K. (Kevin) | GA |

Topograhic Survey

Freeman and Mason

The surveyors established a 17 star position line fix at Stonington, mapped the island at 1:2,000 and carried out sledge wheel and compass survey of adjacent mainland coast and peaks. Nov 1946 Doug Mason travelled north on Plateau to 66.5S and concluded Plateau weather and topography was unsuitable for triangulation and air photo control. March 1947 a route over the plateau to the Larsen Ice Shelf was proved and mapped at 1:250,000

From a baseline on the sea-ice, Reg Freeman observed and beaconed a triangulation scheme for a local map at 1:20,000 scale, including soundings through the sea-ice.

Richard Barrett – Survey Stonington 1974

“Arrivals and Departures” – Kevin Walton

It was March 25, 1946 and midday, the sun was high in the northern sky for we were well South of the Antarctic Circle. It was stllly calm and in actual fact not very cold. Our expedition ship MV Trepassey sounded her farewell on the foghorn and nosed her way out of her sheltered anchorage, headed for the open sea, passed behind the point of Neny Island and was gone.

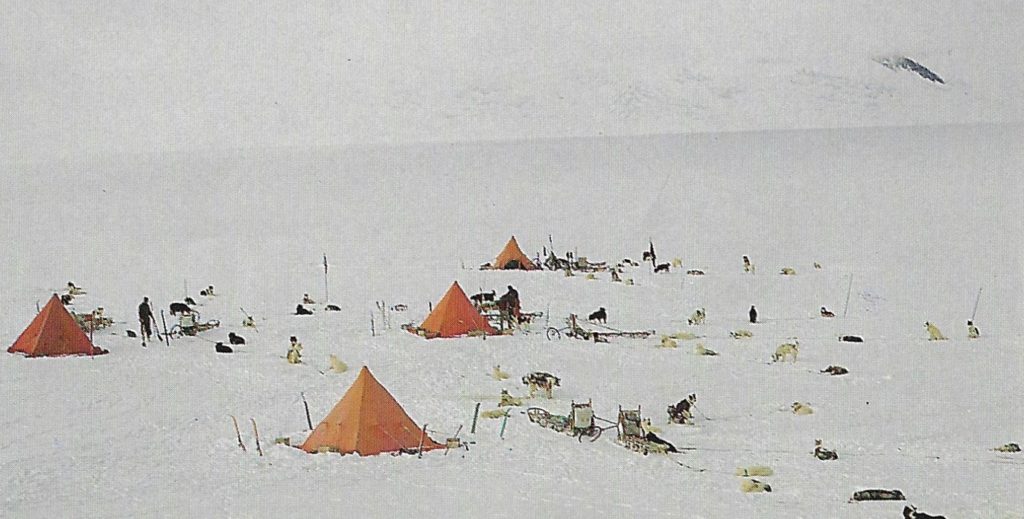

There we were, 10 men and 35 dogs – now entirely on our own. We were truly and utterly isolated.

In fact, in that year we were the only people planning to overwinter South of the Antarctic Circle and on the continent itself. In our area on the West side of the Antarctic Peninsula we did not have the same sense of vastness as those parts of the continent connected with the historic names of Amundsen, Scott and Shackleton. We had no huge glaciers stretching into the distance with a hint of high mountains on the far horizon; we had no miles and miles of floating ice shelf thousands of feet thick with 100ft ice cliffs that made getting ashore almost impossible.

In spite of this the sheer scale of things was for me as great as I have ever experienced in the world before or since.

It was austere, it looked very cold and to my eyes, very wonderful. 12 miles to the East was the main spine of the Antarctic Peninsula; a plateau some 6,000ft high filled the horizon from North to South. From our island base we had our own glacier that appeared to provide a smooth easy highway right up to the plateau. (How wrong we were in fact about the easiness of the route to the plateau for the glacier was a treacherous highway full of crevasses and it formed a funnel for hurricane force winds that would rise in minutes out of a clear blue sky lifting snow and drift, making life impossible and then depart just as quickly). To the West it was all open water flecked with white specks that were floating icebergs and the dark underside of the clouds indicated that this open water stretched many miles beyond the visible horizon.

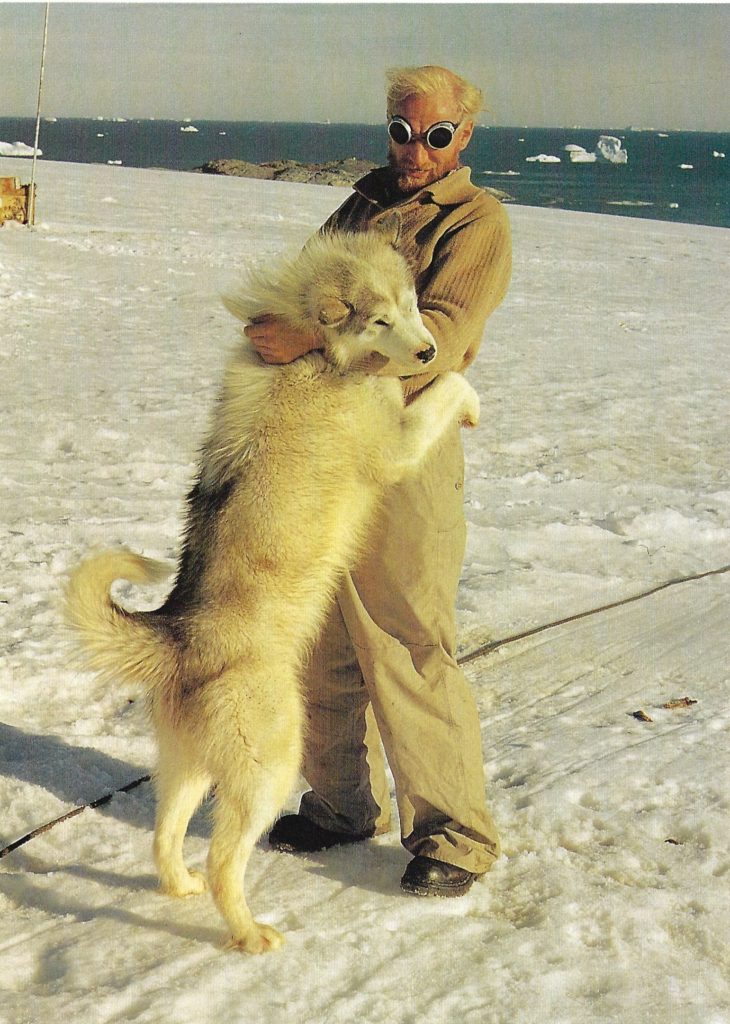

We were a group of men who were voluntarily isolating ourselves on this small island connected rather precariously to the Antarctic mainland; alone that is to say apart from the 35 huskies that we had brought with us; a motley collection, largely untrained and often misfits that had been picked up in ones and twos from the Inuit or trappers of Labrador who, in many cases were glad to be rid of them for reasons of their own.

‘Rover’ and the ‘Orange Bastards’ – Kevin Walton

Under Ted Bingham’s guidance, I chose ‘Rover’ as my lead dog for the ‘Orange Bastards’ and took him out regularly with ‘Darkie’ so that he became familiar with the sound of the commands and what they meant. Learning to steer a compass course was a vital stage in the training procedure: while shouting “Irra” (left), I would flick a 40 foot whip out a few feet to his right, and this made him instinctively veer to the left. With care and constant practice he learnt to hold a course with only occasional prompting, for miles and hours on end.

Lessons from Accidents – Kevin Walton

Some days in Antarctica were especially memorable and such days invariably involved the dogs. These two stories are brief records of two accidents, both of which could easily have been fatal, which taught us lessons we never forgot. One must never walk ahead of a dog team on a glacier and the other was one in which the training of the dogs to drive on a bearing was the reason for the successful outcome of what normally would have had a bad ending.

On August 27th 1946 we were ferrying loads up the Northeast Glacier from Stonington Island to a dump four miles away. Loads were not heavy, there was new snow heavily cut about by the wind, crevasses were well covered and there was no track to follow.

We were only a few hundred yards up the ramp that took us from the Island on to the glacier. The usual line skirted the heavy crevassing on the left and passed about 100yards above the 50ft ice cliff in “Back Bay”. There were 3 teams, with John Tonkin and Ted Bingham in the lead and the day was fine. John’s dogs heard the howling of the dogs on base and as there was no track to follow they decided it would be more fun to bear to the right and take the direct route home.

Early Days at Stonington Island, “Base E”- Kevin Walton (in 1996)

It must be remembered that Stonington Island was only named in 1941 and the term “Base E” was only used from 1946 onwards when FIDS built their base on the island. In the text of “Of Dogs and Men” the chapter on the use of huskies on earlier Antarctic expeditions ended in 1937 with the BGLE. No mention was made of the United States Antarctic Service Expeditions of 1941-42. This omission was intentional for in 1945 when the first of the FIDS expeditions went South there were no records available about what the Americans had achieved. All we knew was that 2 bases had been established, one on the Ross Ice Shelf on the other side of the Continent, near to their 1928/34 bases of “Little America” and one on Stonington Island, on the Antarctic Peninsula, 6 miles South of the Southern base of the BGLE.

When we headed South in Trepassey in 1946 we found the 1941 huts on Stonington still standing

and, apart from being filled with blue ice where doors had been left open, they were in a remarkable

state of preservation. Much of the American equipment was lying around and it was clear that the

place had been “gone over” by visiting ships before we arrived – which explained why the doors had

been left open.

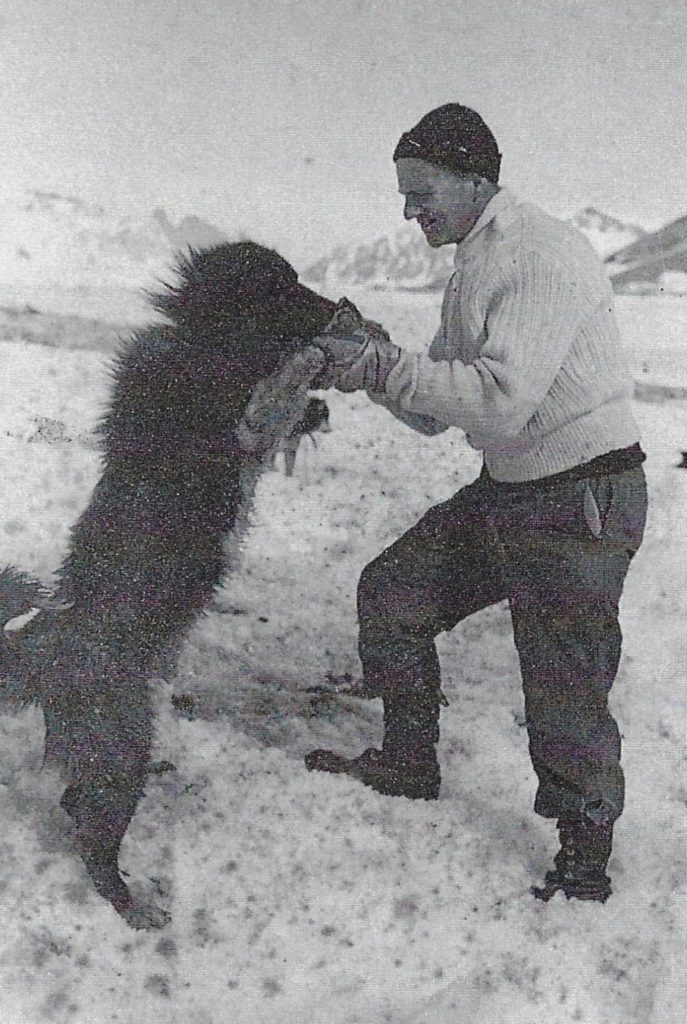

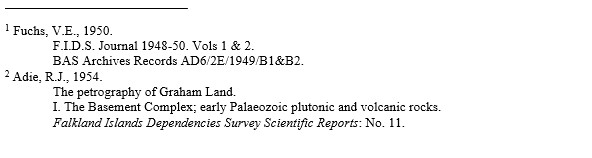

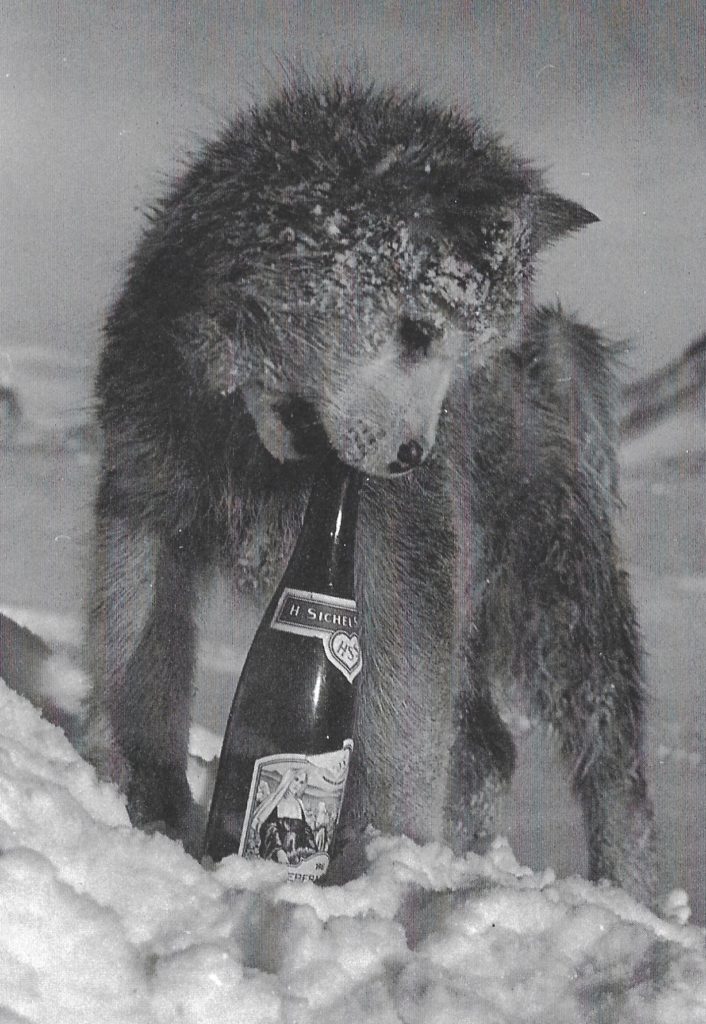

‘Darkie’ – Kevin Walton

(Photo: Kevin Walton)

Trained by Ted Bingham, ‘Darkie’ was the very first team leader at Stonington. He was a ruffian of a dog to look at, with a torn ear, and must have seen a lot of fighting in his youth. But it soon became very apparent that he had excellent eyesight, was very sensitive, and very, very intelligent. Once he was trained to Bingham’s satisfaction, it was relatively easy to use him to teach other leaders. He set a remarkably high standard for them to follow. In 1949 Vivian Fuchs inherited him as a leader. He wrote in his journal that year:

“It was interesting to observe Darkie’s technique when he sensed danger. He advanced cautiously, somewhat in the fashion of a heraldic lion or leopard, each paw each paw extended as far as possible to test the surface in front of him. In this way he found every crevasse and successfully crossed the majority, whereas those behind went blundering into them in spite of the obvious holes he had made. Others would suddenly dash sideways to avoid an imaginary crevasse which was no more than a surface marking in the snow, which Darkie had ignored. Indeed with him ahead, whether be it on glacier on thin sea-ice, I can move forward with the greatest of confidence….”

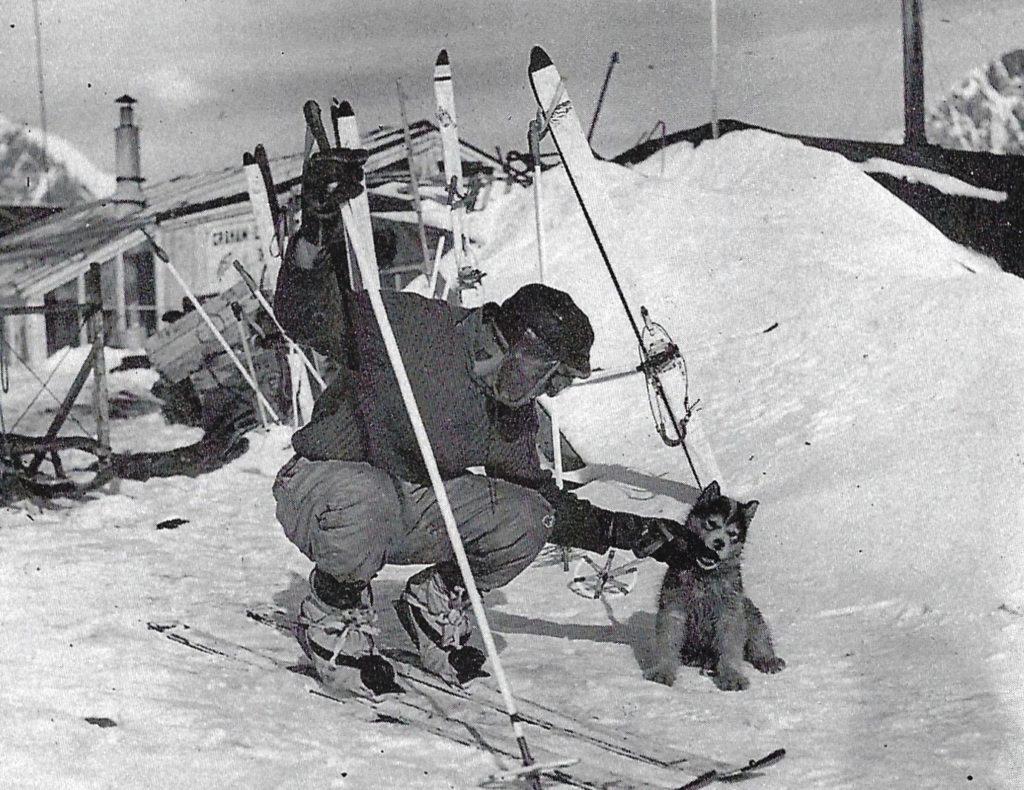

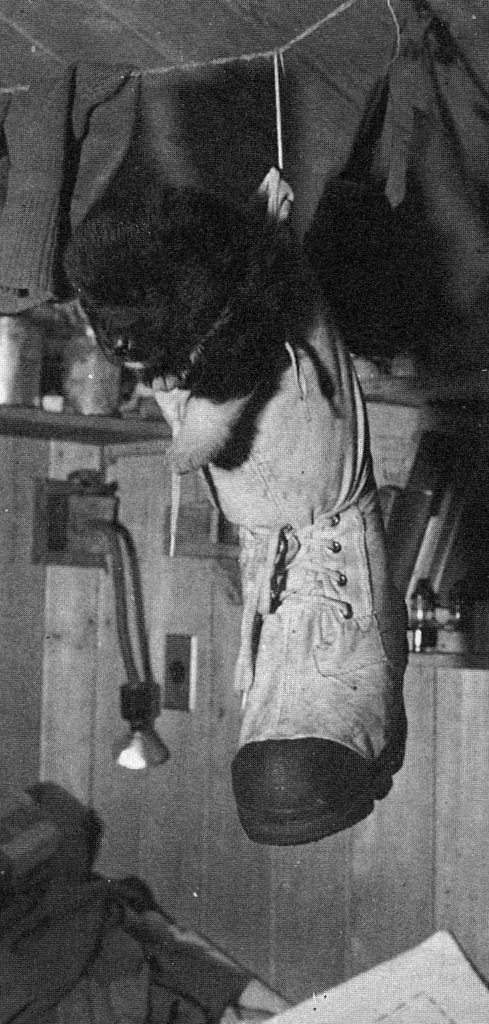

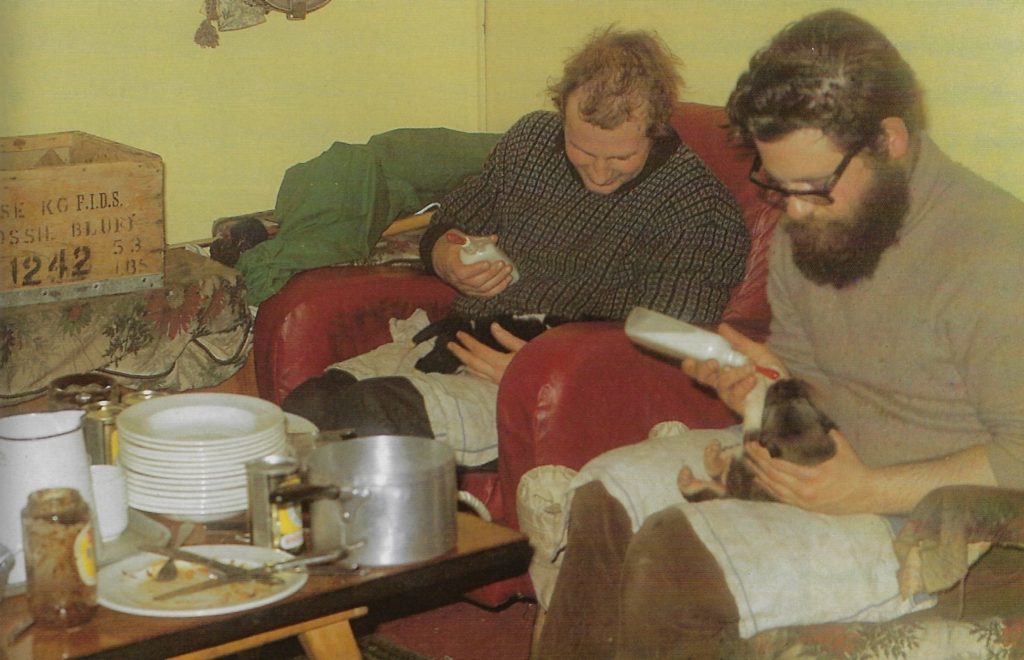

‘Mukluk‘ – Kevin Walton

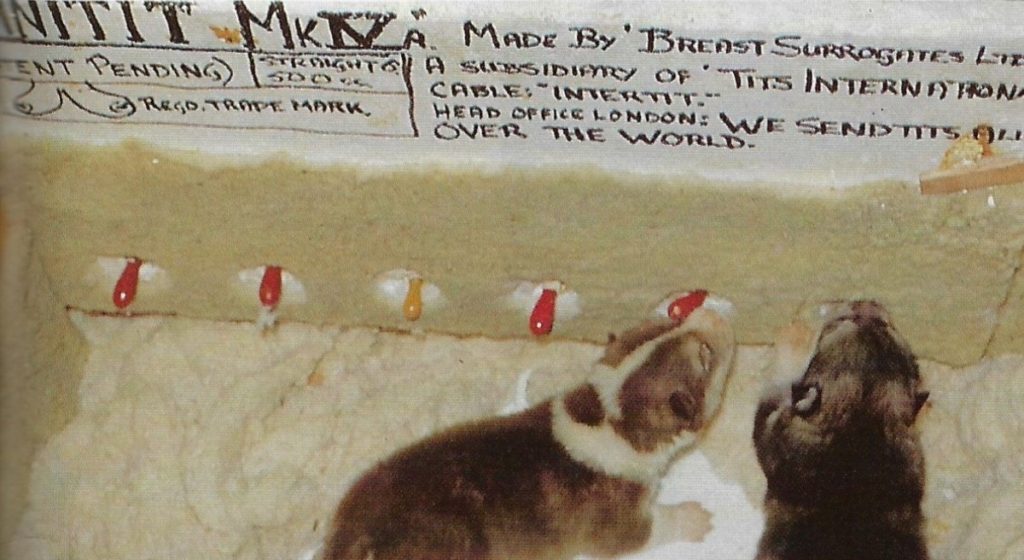

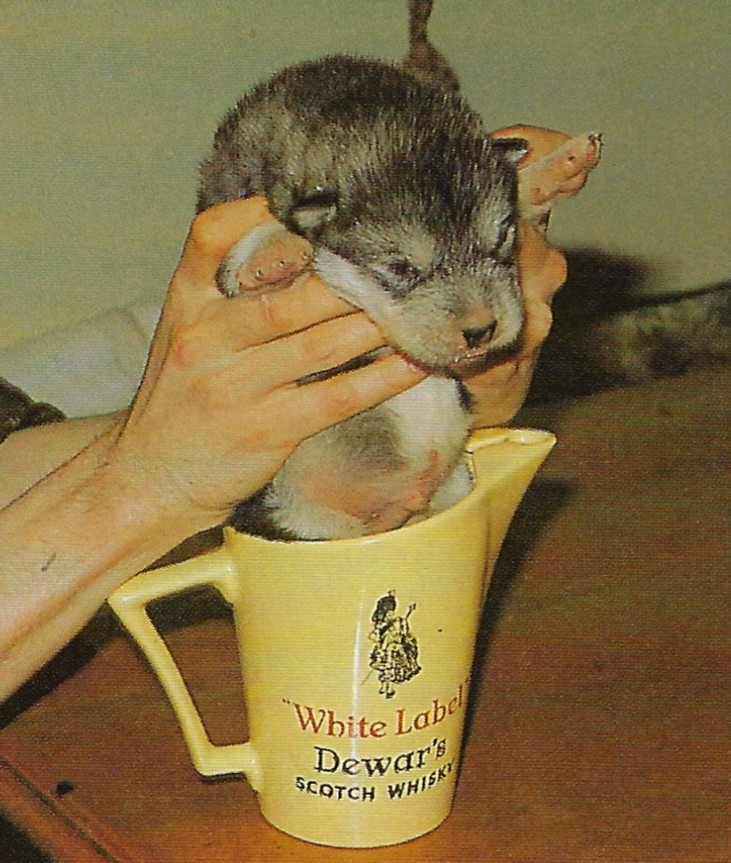

Naming as many as 30 puppies a year was a difficult task and frequently became the cause of fierce arguments.

This one was easy enough, though! She was born unexpectedly in a blizzard, and when we found her she was very cold. We popped her into one of our mukluk boots and hung it above the stove.

“Mukluk” grew up to be a splendid, though timid, breeding bitch.

Kevin Walton, GA – Stonington, 1946 & 1947

1947

Base Commander – K.S. Pierce-Butler

| Butson, A.R.C. (Dick) | Medical Officer |

| Freeman, R.L. (Reg) | Surveyor |

| Jones, H.D. (David) | Air Fitter |

| Mason, D.P. (Douglas) | Surveyor |

| McLeod, K.A. (Ken) | Handyman |

| Pierce-Butler, K.S. (Ken) | Base Commander |

| Randall, T.M. (Terry) | WOM |

| Stonehouse, B. (Bernard) ** | Meteorologist |

| Thomson, W.H. (Tommy) | Pilot |

| Tonkin, J.E. (John) | GA |

| Walton, E.W.K. (Kevin) | GA |

Topographical Survey

Freeman and Mason with RARE

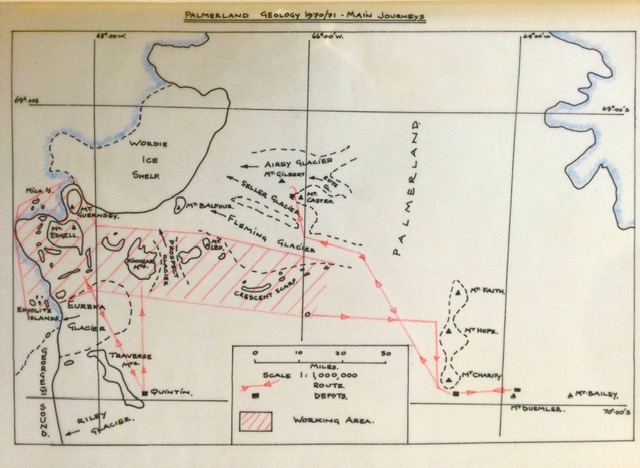

In March 1947, the private US Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition under Finn Ronne reoccupied the old USASE buildings at Stonington and after some discussion instigated a RARE/FIDS survey party under Doug Mason.

The 4 man party supported by RARE planes sledged down the east coast from 68s to nearly 75s where the Bowman Peninsula meets the edge of the Ronne Ice Shelf, travelling 1930km in 105 days. Exploratory surveying by sledge wheel and compass with sun azimuths at camp sites and minor details fixed by compass bearings. Aneroid heights were supplemented by sea level reading in rifts in the ice shelf. Panoramic photographs were taken at survey stations which proved invaluable when plotting the maps back in the UK. Features on the existing maps were found to be up to 80km in error.

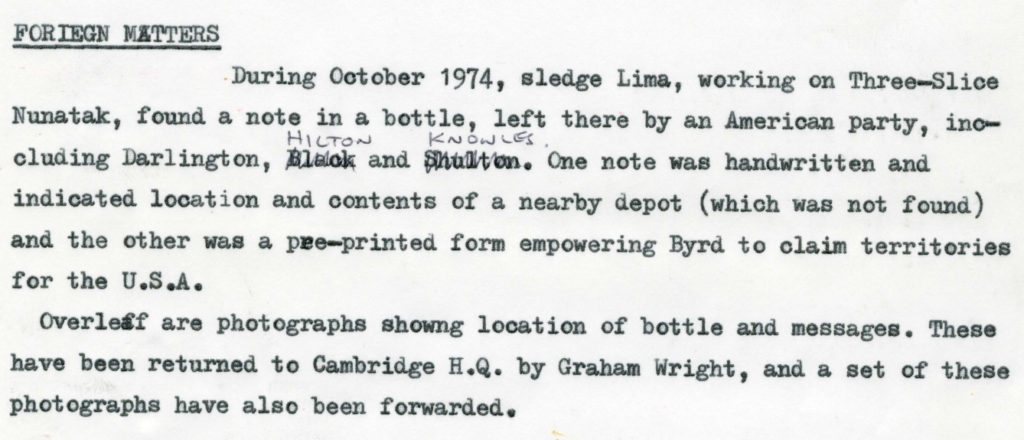

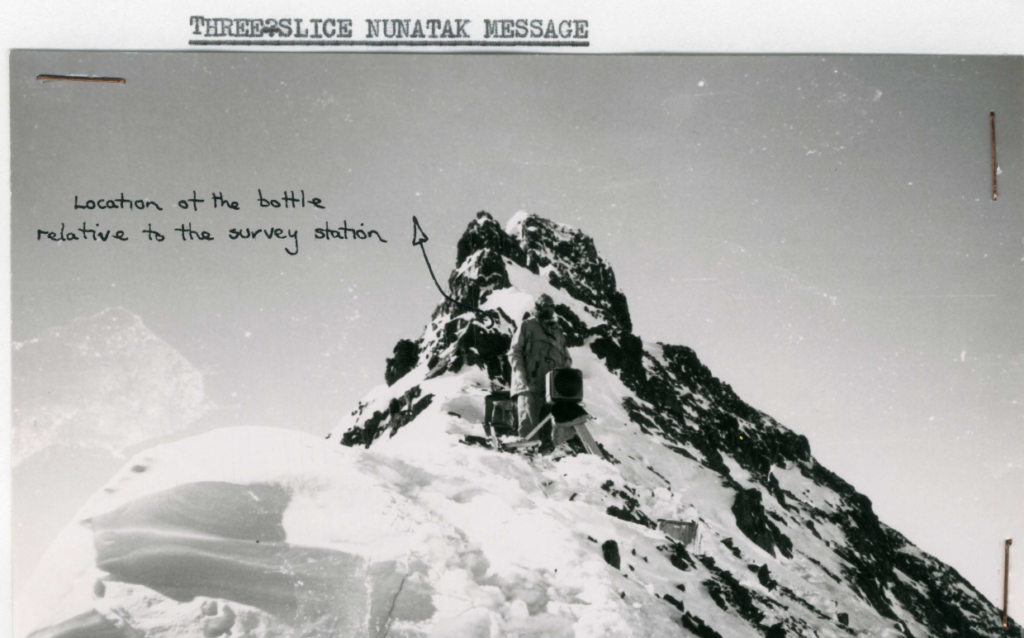

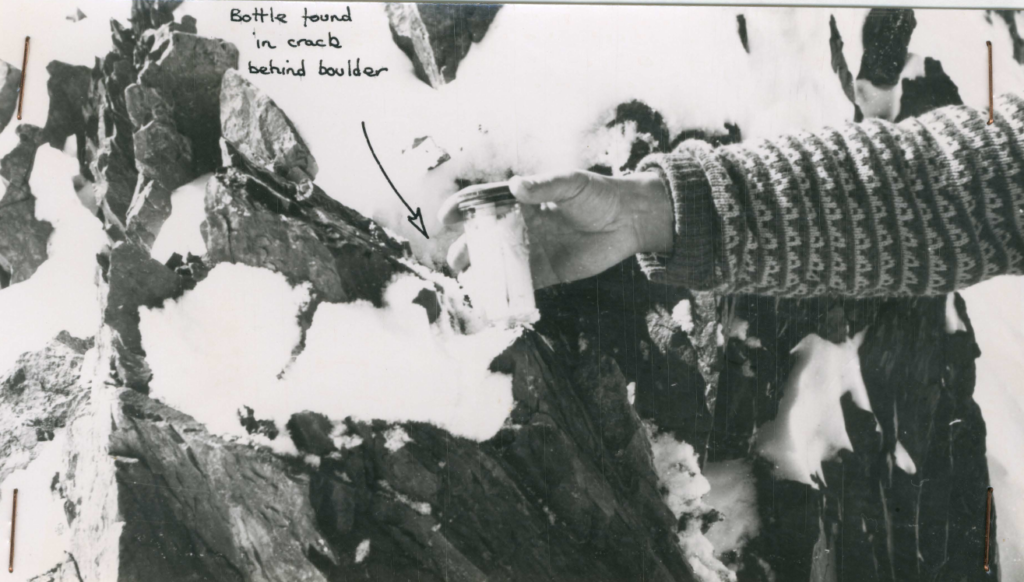

Dec 1947 Reg Freeman led a party to Three Slice Nunatak to meet the Francis party, sledging and surveying south from Hope Bay, and led them back to Stonington.

(The RARE aerial photography was not made available to BAS until 1957.)

Richard Barrett – Surveyor, Stonington 1974

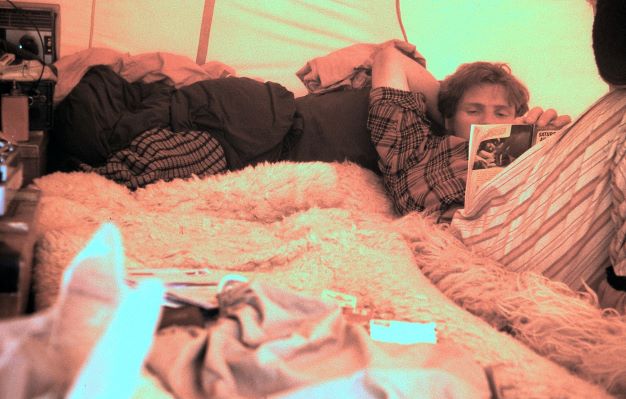

A typical day at Base E, 1946/7 – Kevin Walton

The relationship between dogs and men in the Antarctic is inextricably linked with the quality of life that exists at the base. The closeness of living, particularly with only the wooden walls of the hut separating the men from the dogs outside is part of life.

The Stonington Island base was typical of any of the other FIDS bases. The island was perhaps 200 yards long and in area about 8 acres; there was very little flat ground and the highest point of “Flagstaff Hill” was about 30ft above high water.

The first hut was build downwind of a rounded ridge where it was hoped it would not cover too deeply with drift snow or blow away in the Katabatic wind from the glacier. The hut was 18ft by 30ft and apart from an entrance porch was open plan with 10 bunks set against the walls and a kitchen space at one end. Under the same roof was a small workshop with a separate outside door and a lean to extension reserved for dog equipment.

There was no personal privacy, a feature of all the earlier FIDS huts, no private cabins or indeed anywhere where one could go to get away from the others. Until the base covered up with drift snow most of the dogs tethered outside were in sight from the hut windows. All clean activities from eating, writing up notes, plotting out survey records, sewing or splicing ropes centred around the table which served as a dining table for all meals. The hut was warmed by a single anthracite burning stove and lit at night by paraffin pressure lamps.

Bernard Stonehouse was born in Hull on May 1, 1926. Joining the Fleet Air Arm in 1944, he trained as a pilot, and in 1946 joined FIDS, travelling to Stonington Island on the ‘Trepassey’, as a naval pilot seconded to the Falkland Islands Dependency Survey (FIDS). He also served as a meteorologist, dog driver and, ultimately, biologist.

On September 15, 1947 Stonehouse was deputy pilot when the base’s Auster aircraft took off to mark out a safe landing spot for a larger American twin-engined aircraft which was about to undertake an extensive aerial survey. On the return flight, however, bad weather forced themto make an emergency landing on the sea ice, and the aircraft turned on its back after one of its skis hit an ice hummock. The three men emerged unscathed but were forced to pitch camp on the ice. They had only a small “pup” (two-man) tent, Read on

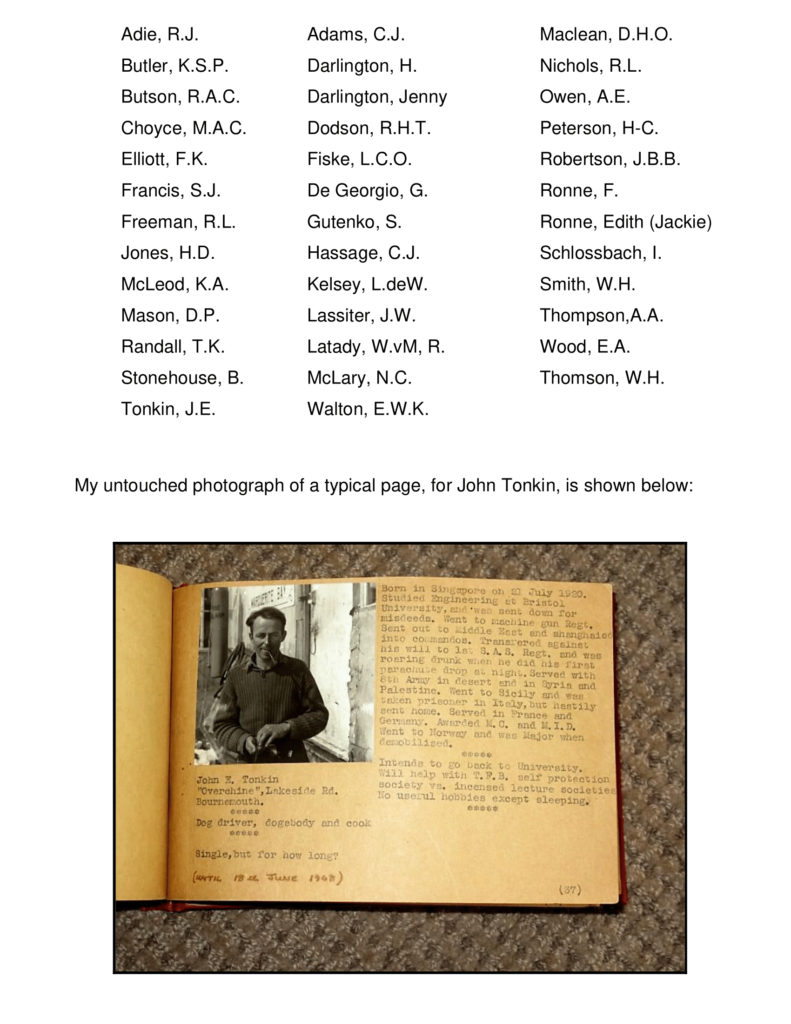

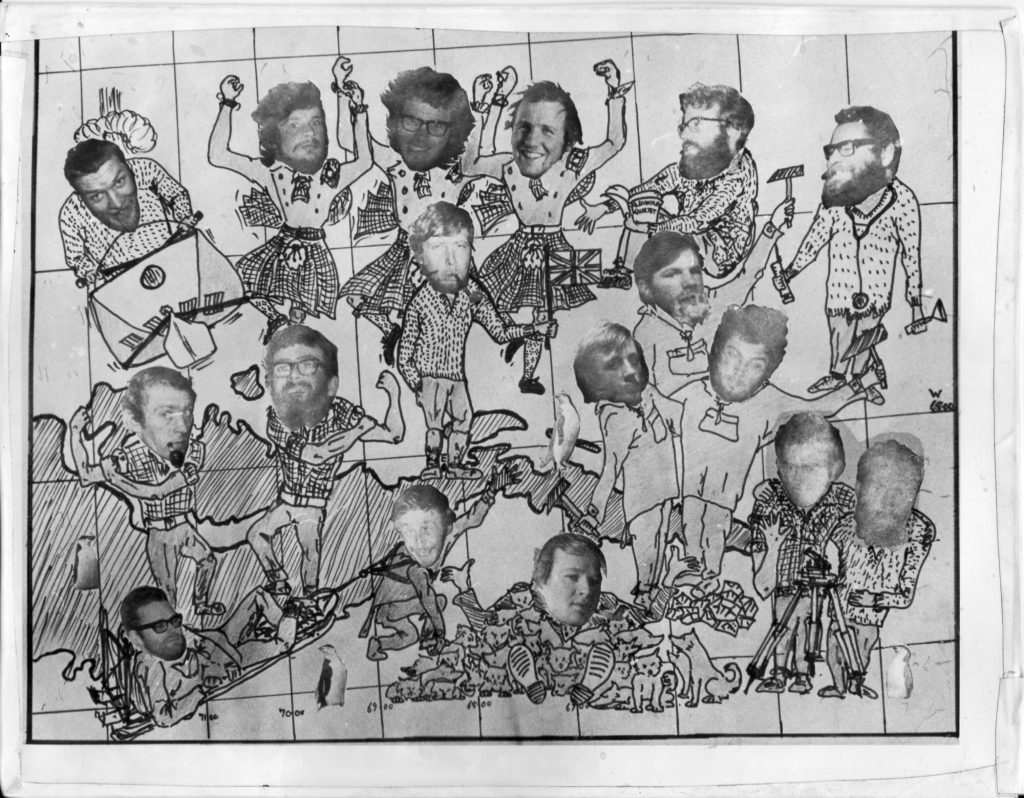

Who’s Who – Keith Holmes

In 2011, I visited Heather Tonkin, in Melbourne, Australia, and she allowed me to photograph a remarkable document that her late husand, John, had compiled on Stonington Island when FIDS found themselves sharing it with the American Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition.

It is a light-hearted vignette of the men and women who were at FIDS Base E, and at the former USASE East Base, probably in early-1948 as it includes the FIDS party from Hope Bay. I don’t recall any reference to it in the published accounts of Kevin Walton, Jenny Darlington, Finne Ronne, Jackie Ronne, or Tommy Thomson, and this is probably the only surviving version of it.

John’s daughter, Jane Storey, most kindly donated it to BAS Archives last year, along with a lot of other excellent archive material.

The booklet comprises 41 pages of faded brown paper, stiff-bound in red material, with a title page bearing a photograph of the two bases, two summary pages recording how long the formal parties spent on the island, and typescript entries for 38 individuals as follows:

For the edited photos of all the pages, see here:

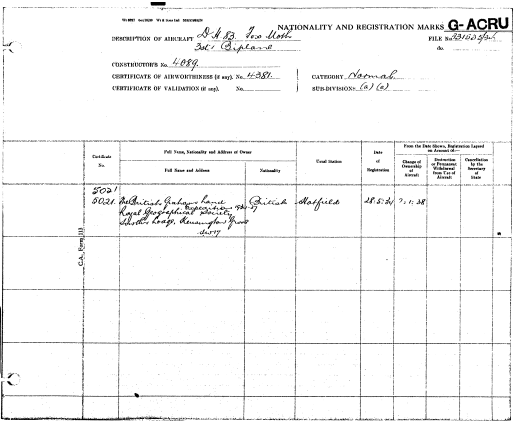

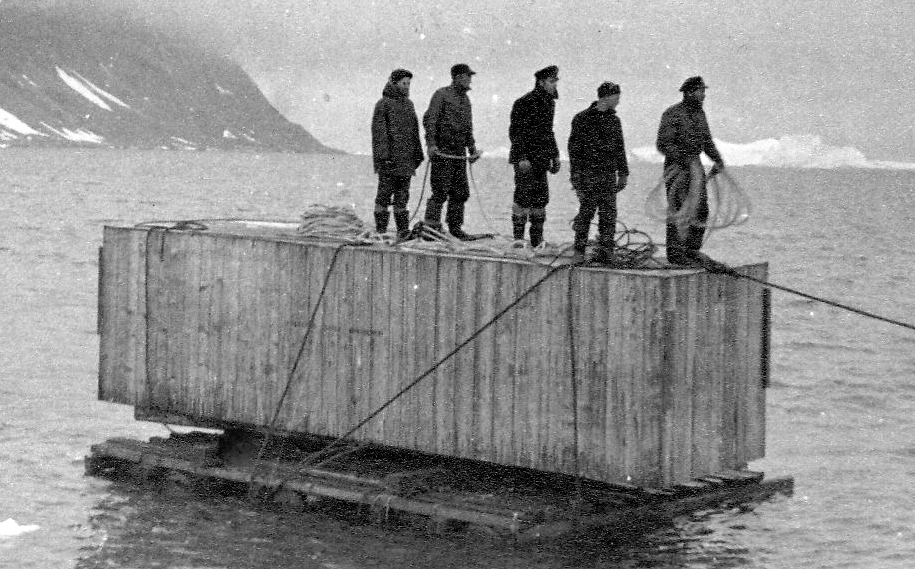

Aircraft G-AIBI – Auster Autocrat (“Ice Cold Katy”) – Keith Holmes

GA-AIBI was purchased in 1946 by FIDS, and fitted with skis, but for some reason the tail skid was replaced, in England, by a tail wheel. Better known as ‘Ice Cold Katy’, the aircraft was shipped from Stanley to Stonington. The new Auster J/1 Autocrat aircraft, which had been registered in Britain as G-AIBI, arrived off Stonington Island, in a crate, aboard MV Trepassey on February 5th. John Tonkin photographed it being rafted ashore the following day, and noted that it weighed thirty hundredweight[1].

The aircraft had been accompanied by a pilot, Bill ‘Tommy’ Thomson, and by David Jones, an Aircraft Engineer. ‘Tommy’ kept a diary of what he did with the aircraft [2] and later published an autobiography which looked back on his experience[3]. David also wrote a formal report on the aircraft’s performance. In retrospect, both men were, by and large, satisfied with how it performed. There were, however, early set-backs. Read more here.

MV Trepassey’s Newfoundland Crew – Brian Hill

The m/v Trepassey was out of St. John’s, Newfoundland on her 2nd Antarctic trip. Newfoundlanders are quite adept at towing things around on rafts. Read more about the Newfoundland Crew here….

Operations & Incidents with ‘Ice Cold Katy’ – Reg Freeman

Reproduced by Permission of BAS Club – Newsletters 23 and 24

(Photo: Kevin Walton)

The story as experienced by the party later in the winter, working to lay depots for the winter journeys. It became an epic incident, resulting in the journey by the three crew to return to Stonington, with no dog teams or other transport, rivalling some of the more well-known and publicised epic journeys. It is an enthralling read of Reg Freeman’s journal, with photos added from the book by Kevin Walton “Two Years in the Antarctic”.

Grab a dram and settle down to read.

Mount Tricorn at approximately latitude 74°S, longitude 62°W, was anticipated as being the most southerly point which would be reached by the proposed sledging party. (Later it was proven that the estimated position of Mount Tricorn was 50 miles in error!).

Journey to the East Coast and Bill’s Gulch – Dick Butson

Starting March 2nd, 1947, Dick Butson took part in a 40 day trip up North East Glacier, up Sodabread slope and over the Plateau to the cliffs overlooking Bill’s Gulch.

This description taken partly from his diary and partly written from memory 40 years later describes a very frightening episode which was part of the autumn reconnaissance. The camp from which the story starts was on the plateau about 4 miles from the cliffs overlooking Bill’s Gulch 60 miles from home on the East coast.

8th April

A wonderfully clear day. Set off with Dougie and John with his team to recce the route leading towards Bill’s Gulch. Horizon after horizon appeared deceptively near. After about six miles we had a wonderful view of the glacier, the lower half from about 3,000 feet being in cloud. We were at about 5000 feet having travelled down a narrowing valley which we identified as the start of Bill’s Gulch. As we climbed back out of the shelter of the valley we realised that in travelling down wind we had not realised just how much the wind had increased. The drift was intense coming full in our faces. Using both our prismatic compasses we went back on the reverse of our outward journey. The wind had completely obliterated our outward tracks and was so strong that the dogs would not face it by themselves. With John and Dougie in front on snowshoes, each with a prismatic compass, and me on the sledge with the sledge compass as an extra check we kept reasonable course with the dogs following the men in front and me following the dogs. As the wind and drift increased I could barely see the dogs and only very occasionally the two men ahead. We stopped and conferred on two occasions..

Reminiscences – Dick Butson

Friday April 25

It had been noticed that Hugh was in trouble with diarrhoea for some days and I noticed this morning that he had not even touched his meat from yesterday. He was definitely ill and listless. I dosed him with castor oil at 1130. By 1800 he was distinctly worse and he made no attempt to resist examination. We brought him into the workshop, he had 168 pulse and rectal temperature around 100.7. His intestines were rock hard and there was evidence of peristalsis. He had only managed one small watery stool since his dose of castor oil. We decided that he had probably got a piece of bone stuck in his intestines and laparotomy was decided upon as he was going down hill very fast. We started to prepare to operate at 2030 and started at 2130. Ken Butler administered the anaesthetic, ethyl chloride followed by ether.

The rectus, linea alba and peritoneum were divided with no bleeding. The gut was found to be hyperaemic and a 9 inch long intussusception was found in the small gut and this was reduced by gentle traction and there were no signs of adhesions. The invaginated portion of the gut was back to its normal colour except for a small segment about 1/4 inch long. I warmed this with a pad soaked in warm water and it quickly recovered colour. I closed up the abdomen with continuous catgut and the skin with silk sutures. The whole operation lasted 45 minutes. He came round about midnight, and passed a watery stool in the coal bucket and remiained indoors for two days and recovered in about ten days. (Hugh did very well and worked for the next two years and sadly had to be put down when Stonington Island Base was abandoned in 1950).

Dick Butson – Medical Officer – Stonington 1947

1948

Base Commander – Vivian Fuchs

| Adie, R.J. (Ray) | Geologist |

| Blaiklock, K.V. (Ken) | Surveyor |

| Brown, C.C. (Colin) | Surveyor |

| Dalgliesh, D.G. (David) | Medical Officer |

| Fuchs, V.E. (Vivian) | Geologist |

| Huckle, J.S.R. (John) | GA |

| Jones, H.D. (David) | Air Fitter |

| Randall, T.M. (Terry) | WOM |

| Spivey, R.E. (Bob) | GA |

| Stonehouse, B. (Bernard) | Meteorologist |

| Toynbee, P.A. (Pat) | Pilot |

Earth Sciences

Vivian Fuchs applied for a position as Geologist, was interviewed and offered the job of overall Field Commander of all the Antarctic activities, based at Stonington.

Fuchs and Ray Adie were the Geologists on the expedition, two of 27 Fids to travel to the Antarctic in December 1947, and they were given the freedom to plan the scientific programme for the duration of their stay. At Stonington, eleven men lived in cramped quarters and Fuchs quickly became the natural, as well as the appointed, leader of the group. Between 1948 and 1950 the men made a series of expeditions south from their base on the Peninsula. Read on

Topographic Survey

Brown and Blaiklock

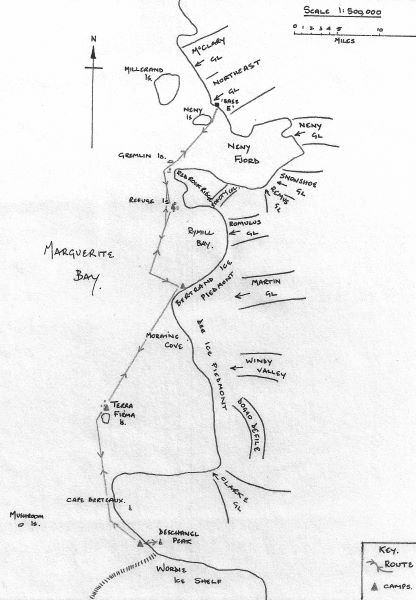

Colin Brown carried out exploratory survey of the coast south from base to Cape Jeremy, positioned the islands in southern Marguerite Bay and the NE coast of Alexander Island.

Ken Blaiklock surveyed the islands in northern Marguerite Bay and the east coast of Adelaide Island as far as The Gullet where there was open water and discovered the emperor penguin rookery on the Dion Islands. He surveyed the fjord area running closed traverses around the major islands.

In mid-winter 1949 Blaiklock visited the Faure Islands and carried out an astro-fix but the sight of open water brought a hasty conclusion to the work.

Between major journeys the surveyors continued the local triangulation started by Reg Freeman.

From 1952 to 1954 Ken Blaiklock was employed as a surveyor at Base D, Hope Bay. In 1955 he served on the MV Norsel as a surveyor and helped to set up two bases on the Peninsula.

Later, Ken was part of Fuchs’s Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition in 1956-1958 that completed the first overland crossing of Antarctica. He was leader of the advance party which set up Shackleton and then he was part of the crossing party during which, with Jon Stephenson, drove dog teams to the South Pole for the first time since Amundsen. Ken completed the Antarctic crossing by reaching Scott Base aboard the Sno-Cat “County of Kent”. Read more about Ken and TAE here….

From 1959 to 1961, Ken joined the second Belgian Antarctic Expedition with Captain Bastin which failed to reach the South Pole. In 1965 he worked for BAS on Adelaide Island and on the Peninsula. He did more survey work in the Antarctic and for Decca in the North Sea before retiring in 1996.

Ken Blaiklock was awarded the Polar Medal with three bars along with many other awards.

Richard Barrett – Surveyor, Stonington 1974

Heading Home with the Choristers – Bernard Stonehouse

Over fifty days after leaving base, we were on our way home. Three nights and two days of gale had held us down, giving us the lie-up we needed after a week’s hard running. Now we were ready to move on. That morning the wind had dropped, tent canvas no longer flapped, drifting snow was stilled, and the sun shone warmly through the peak of the tent. We emerged to a glorious day — calm, clear and brilliant.

Alert to our movements, the dogs rose as we did, popping up from the snowdrifts that had built up around them, stretching, yawning, shaking ice from their matted fur, greeting us with warmth and wagging tails. They watched as we dug out tents, boxes, sledges and traces, growling sotto voce to each other, from time to time setting up the chorus of song that bonded them as a community — three teams of nine, offering friendship without question to the four men who moved among them. Harnessing brought them to a crescendo of excitement. As the first team moved off, those remaining leapt in their traces. I had often wished I could raise even half their blessed enthusiasm at the start of the hard day’s sledging.

My team was the Choristers, a nickname earned by their penchant for bursting into song. From time to time I sang to them, and during the ten-minute breaks they sang to me and to each other. I sang Hymns Ancient and Modern, Handel, Gilbert and Sullivan, Schubert, and a Bing Crosby-Andrews Sisters medley.

Arrivals and Departures – David Dalgleish

Our ship lay at the edge of the unbroken sea-ice, 4 to 6 feet thick, too much for our small vessel. We gazed to the East at a steep sided 2000ft high island which lay between us and our destination, a mere 30 miles away. It was surrounded by this flat unbroken white plain, behind which stretched the 6000ft high Graham Land Plateau. It was a sunlit scene on indescribable beauty, silent and awesome. Absorbing all this we waited for the ice breaker that would lead us in and then saw distant specks which materialised into two sledges with a man apiece, each pulled by nine dogs. They skimmed over the white plain – such energy, such control and such assurance. Mutual greetings were shouted upon their arrival.

Later on we were near the shore of our future home and for the next hours we accompanied these men and their teams landing many tons of stores until late into the night – although of course the sun was still shining! How could one possibly learn to control 9 dogs with such assurance – the suddenly I heard “just take my team back please” and we had to learn the hard way.

At last all was complete, goodbyes and emotional departures for the outgoing dog-drivers – but what a wonderful legacy they left us.

Aircraft VP-FAE – de Havilland DH.87B Hornet Moth

Purchased by FIDS as a readily-available, urgent replacement for their Auster J/1N Autocrat G-AIBI ‘Ice Cold Katy‘ destroyed in an accident September 15th, 1949 (see ‘Ice Cold Katy’ above). Re-registered as G-ADMO on November 26th 1947, it was crated and shipped from Southampton on ‘John Biscoe‘ to Deception Island, arriving there on February 2nd, 1948. Although unloaded onto the beach there was no point unpacking it because, due to a loading oversight, no skis had been sent with the aircraft!!

And so, for some, their third consecutive winter!

1949

| Adie, R.J. (Ray) | Geologist |

| Blaiklock, K.V. (Ken) | Surveyor |

| Brown, C.C. (Colin) | Surveyor |

| Dalgliesh, D.G. (David) | Medical Officer |

| Fuchs, V.E. (Vivian) | Cdr FIDS, Geologist |

| Huckle, J.S.R. (John) | GA |

| Jones, H.D. (David Jones) | Air Fitter |

| Randall, T.M. (Terry Randall) | WOM |

| Spivey, R.E. (Bob) | GA |

| Stonehouse, B. (Bernard) | Meteorologist, Zoologist |

| Toynbee, P.A. (Pat) | Pilot |

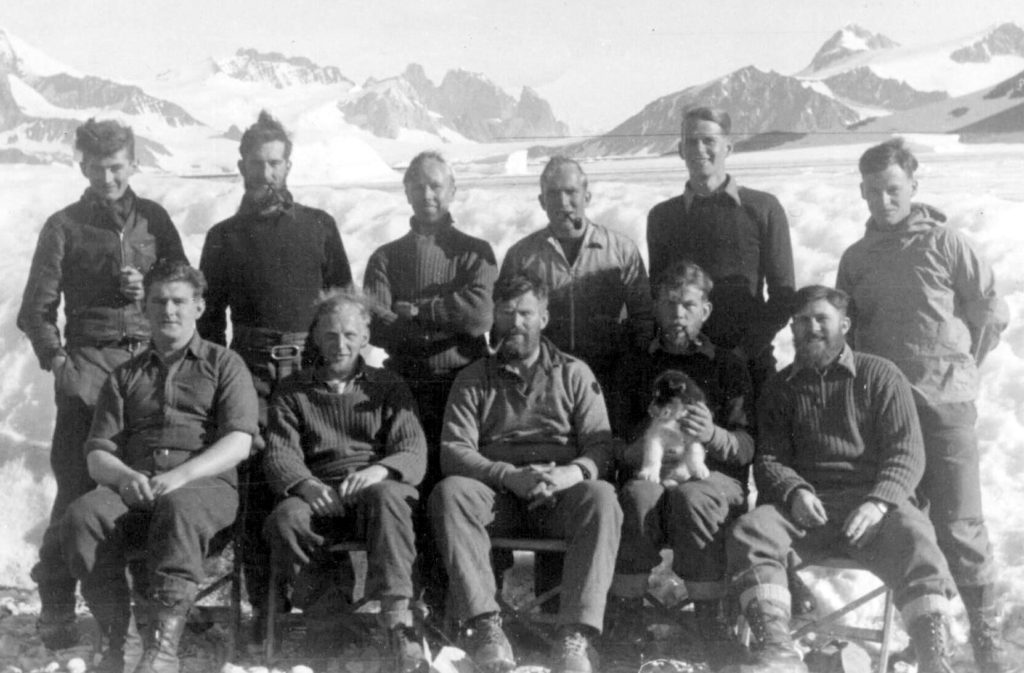

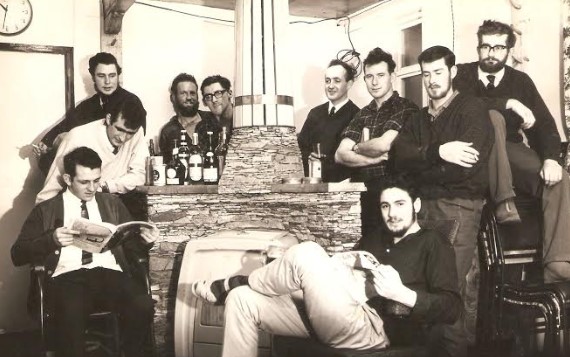

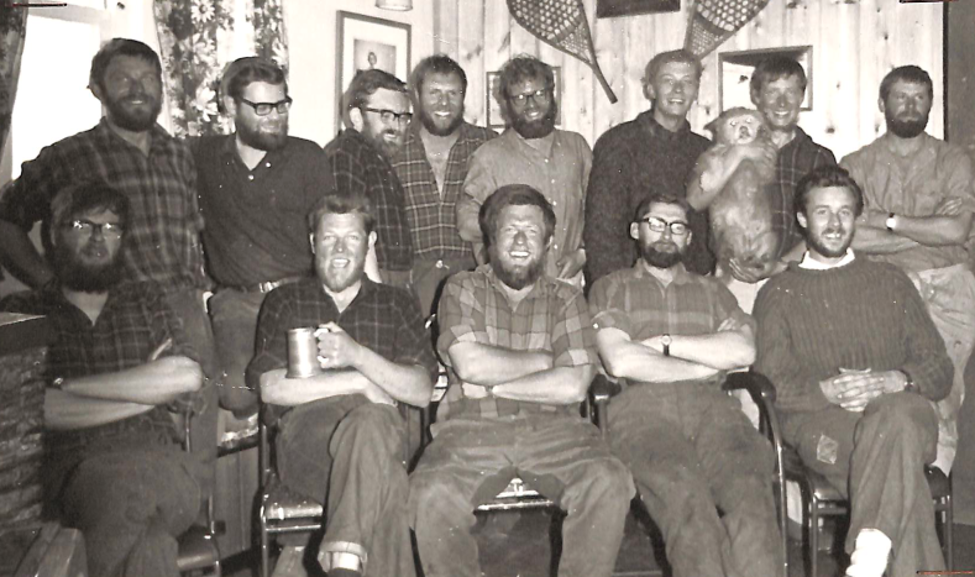

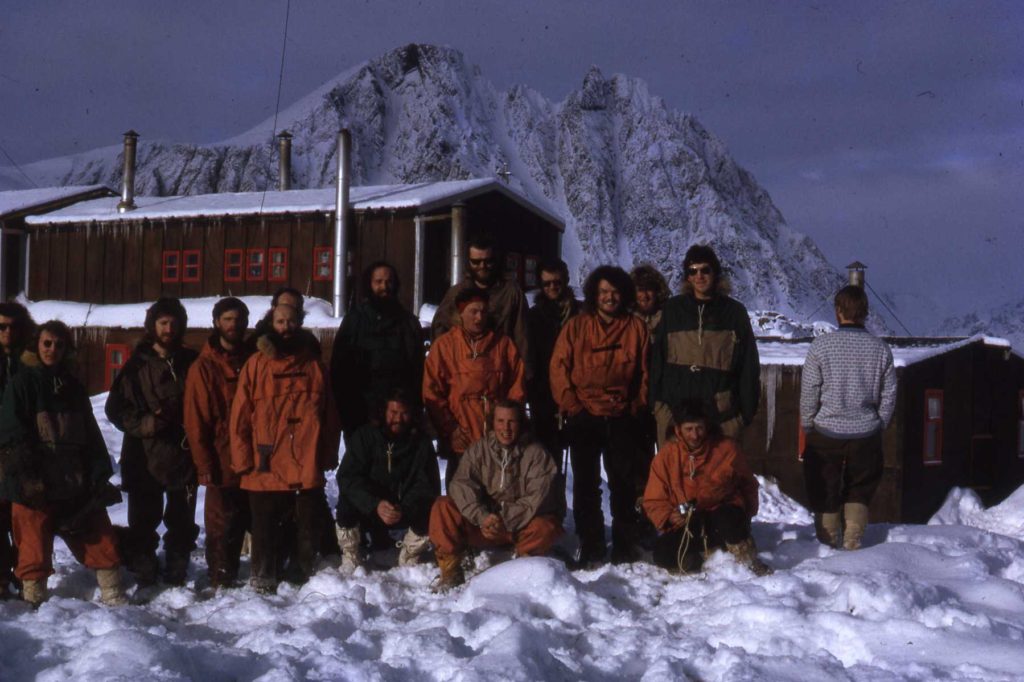

Back Row from L to R: Bernard Stonehouse, John Huckle, Bob Spivey, David Jones, David Dalgliesh, Colin Brown

Seated from L to R: Terry Randall, Ken Blaiklock, Vivian Fuchs, Pat Toynbee, Ray Adie

(Photos By Bob Spivey via Una Spivey to Keith Holmes)

Topograhic Survey

Brown and Blaiklock

The good sea ice of 1949 which had allowed the surveyors to complete historic journeys displayed on the maps for a generation of Marguerite Bay Fids, now failed to go out and allow the relief. The Stonington Fids became “The Lost Eleven” of news headlines.

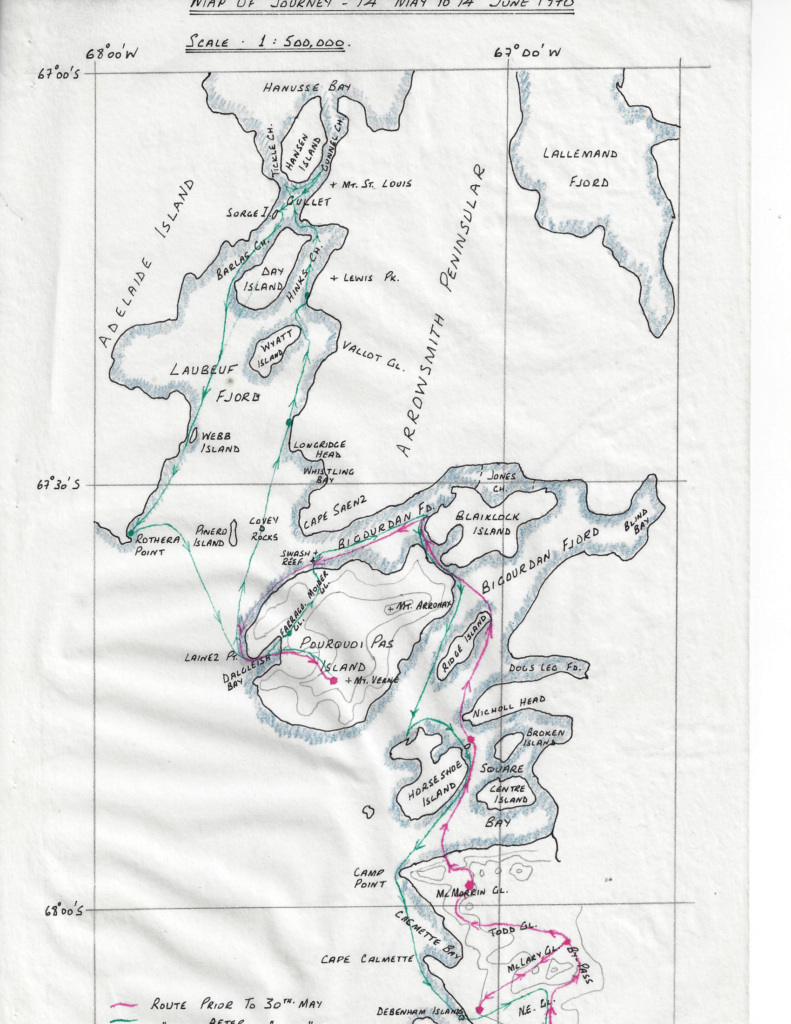

The powers that be allowed some amateur surveyors, geologists Fuchs and Adie, to survey the southern coast of Alexander Island and in the area of Buttress Nunataks on their journey to Eklund Island. Brown accompanied this party down the King George VI Sound to Ablation Point to link up his 1949 work with BGLE surveys. Blaiklock went north and surveyed Bourgeois and Bigourdan Fjords.

The decision was taken to close Stonington and the RRS John Biscoe arrived and closed the base in Feb 1950.

Stonington and Many Other Occasions Since – Ken Blaiklock

I was looking up at the stars one clear winter’s night and could see Sinus, the brightest star in the constellation of Canis Major. Sinus the Dog Star. One word suggested another and brought a new train of images. Sirius the Dog Star – alpha Canis Major – a Husky dog called Major – and then dog sledging down South.

All sledgers will have their memories of dog sledging days in Antarctica. Days of drama, such as the rescue of an American in a crevasse in North-East Glacier by the 1947 FIDS at Stonington Island base; or arriving by dog-team at the Amundsen-Scott base at the Pole. Days of danger and fear – a sledge breaking through thin sea ice and floundering in the slushy ice; or dogs down a crevasse and you hope you can haul them up before they wriggle out of their harnesses and fall to their death. Days of discomfort such as on a late autumn depot-laying trip with heavy loads, short hours of daylight, the wind blowing drift snow into your face, and you are cold and tired and miserable.

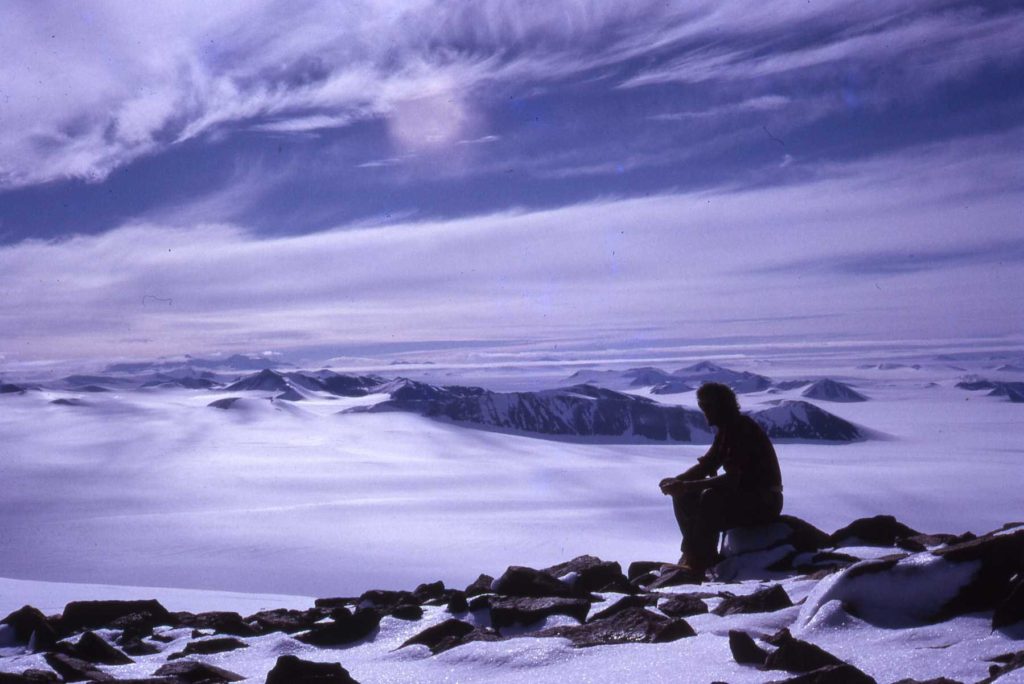

But the days always remembered best are the days of delight, when everything seems perfect and you are exhilarated with joy, contentment and achievement.

It was such a day’s sledging I recall with David Stratton. A couple of weeks beforehand we had been flown from the base in the Otter aircraft to the western end of the Shackleton Mountains. We had been sledging eastwards and that morning looking out of the tent we found a brilliant clear sky, an absolutely calm and crisp feel in the air although the sun was already warming the tent. The dogs stirred and gave us an early welcome and soon we had the tent down and the sledge loaded and lashed. Off we went up a long smooth gentle slope with low flat-topped hill on either side. It was an excellent surface for sledging on firm hard snow with no sastrugi and crevasse-free, and a lightly loaded sledge. The miles ticked by on the sledge wheel counter and we had almost made the rest of the pass by lunchtime. As we later approached the pass summit, the tops of mountain peaks began to appear, and then a whole new range came into view. Peak after peak ahead stretching to the horizon and all uncharted and unvisited. Down we sledged in a glorious run to a bluff some miles away. We camped after a run of 27 miles. Not the longest distance achieved on one day by any means, but very satisfying.

Sitting on a ration box outside, tired but happy, I could look at all the mountains ahead, while waiting for the inside man to cook dinner. To cap the end of a memorable day, we went out after our meal to watch a total eclipse of the sun. The moon moved over the sun’s disc and when the sun was totally covered, the sun’s corona was visible for a few minutes. The dogs all raised their heads and started to bay in unison, with their haunting moan.

Many sledgers will have such Dog-Day memories of 10,20,30 and even 40 years ago. But it all seems like yesterday.

Ken Blaiklock – September 1995

Aircraft VP-FAC AUSTER MK. 5

VP-FAC departed (crated) on ‘John Biscoe‘ from Southampton on October 12th, 1949, for Deception, where it was unloaded, assembled and then air-tested on December 18th, 1949. Flown as a floatplane from there to the Argentine Islands to rendezvous with (and be based on) ‘John Biscoe‘. Piloted by Flt. Lt. John Lewis, it reconnoitred open sea routes around ice floes and clear water areas close to Stonington Island in Marguerite Bay, Graham Land before the 11 Fids marooned on Stonington were rescued in three groups by the Norseman VP-FAD (see below) and ‘John Biscoe‘ between January 30th, 1950 and February 2nd, 1950.

Aircraft VP-FAD NORSEMAN MK.5

VP-FAD was the last Norseman ever built. Purchased in 1949 by Fids, it was configured as a Seaplane and fitted with floats. It was shipped to Deception Island for assembly and then joined VP-FAC in operating from ‘John Biscoe’ during the relief (rescue mission) of Stonington, arriving there on January 30th, 1950. Hired to Falkland Islands Government in 1951 prior to sale to them.

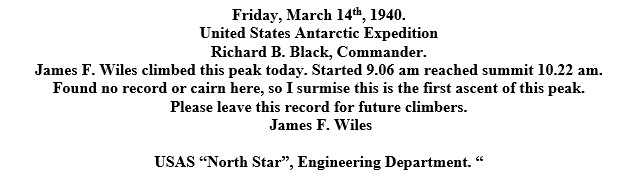

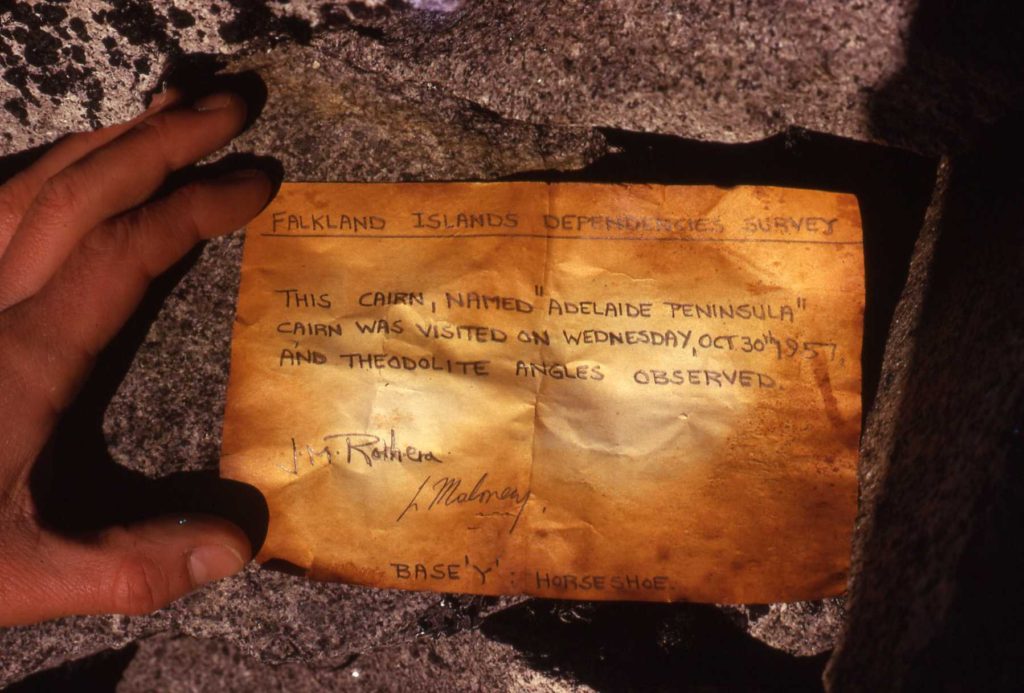

The First and Second Ascents of Neny Island – Keith Holmes

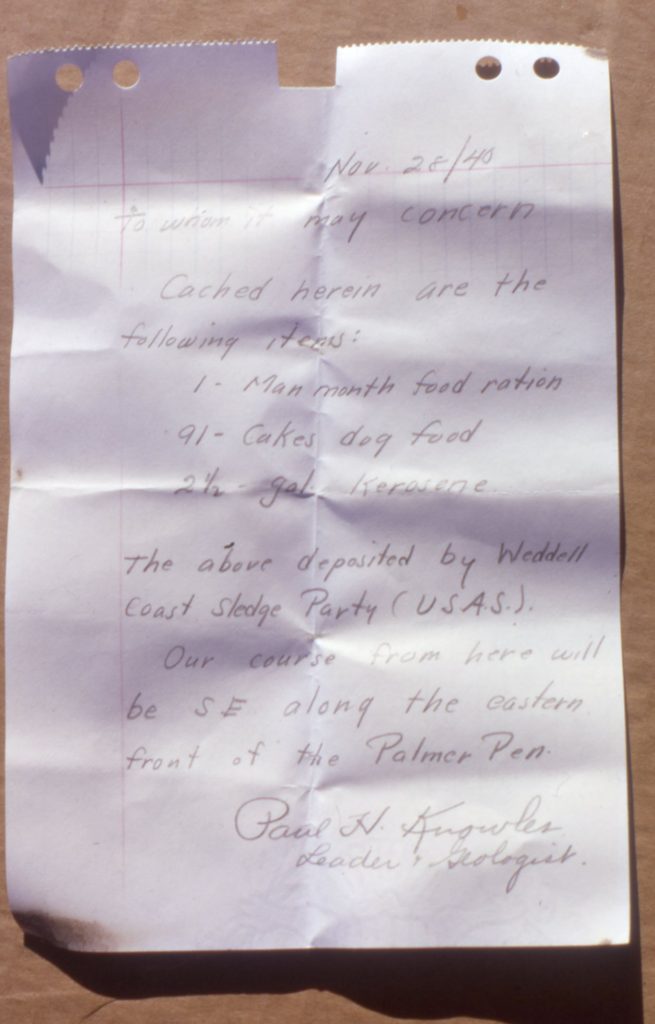

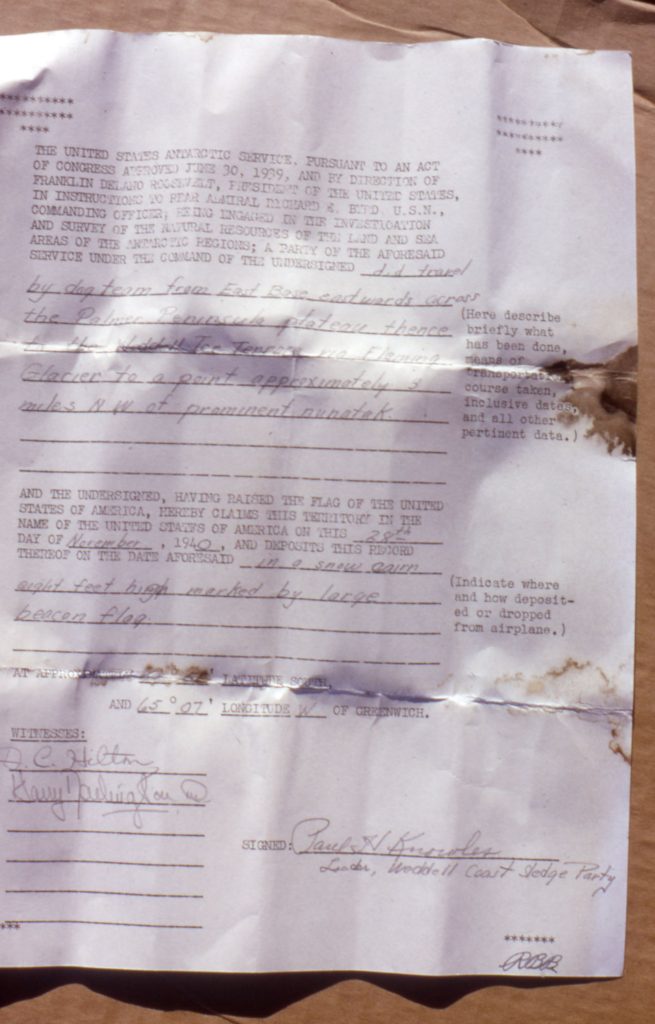

On January 24th, 1950, the F.I.D.S Journal recorded [1] that John Huckle and Vivian Fuchs climbed Neny Island, and at the summit found a glass jar containing the following message:

From the top, Fuchs drew a sketch of the Northeast Glacier, showing its snout extending to the shore of Neny Island, as seen also in an aerial photograph later published by Ray Adie.[2]

1958

Base Commander – Peter Gibbs

| Forster, P. D. (Peter) | Surveyor |

| Gibbs, P.McC. (Peter) | BL, Surveyor |

| Hoskins, A.K. (Keith) | Geologist |

| Procter, N.A.A. (Nigel) | Geologist |

| Roberts, B.R. (Brin) | Radio Operator |

| Wyatt, H.T. (Henry) | MO, Physiologist |

Stonington Reoccupied – (8 March 58 to 7 March 59) – Peter Gibbs

When the Biscoe landed the 6 of us and 3 dog teams (from Horseshoe Island) on the 8th March ’58 we were a little dismayed to find up to 2’6″ of ice throughout the floor of the old British hut and a dead dog in the American huts abandoned about 10 years before. But we set to with a will as we had an ambitious program of survey, geology, human physiology and dog-feed trials to do. Apart from the last which was planned for mid June to mid July we intended to be in the field the year round.

We had the hut habitable within 2 weeks, built 3 sledges and made up traces and harnesses by the 3rd week and set out on the first journey up the Northeast Glacier on the 10th April.

There were six of us, four with the previous year’s experience. Henry Wyatt (doctor from Base W), Nigel Proctor, (geologist from Horseshoe), Bryn Roberts, (radio from Horseshoe) and myself. Two newcomers in their first year were Pete Forster (surveyor), and Keith Hoskins (geology). We had three 9 – dog teams, the Admirals (mine). Churchmen (Nigel) and Spartans (Bryn). This had left two teams at Horseshoe for breeding and local running as they had a static program. But I had planned with John Paisley the new base leader at Horseshoe, that they would assist us in the spring with depot laying journeys to the Wordie Ice Shelf. In the event most of these dogs did join us later, thanks to miraculous survival, as I shall tell; and for the spring work we made up a fourth team, the Moomins, driven by Henry.

It was a year in which the Admirals took me some 1240 miles sledging on 243 days and I expect the figures for the Churchmen may have been similar. We travelled through the midwinter period again, as events turned out. It was a year when all the events revolved around the dogs and their drivers, the successful inland journeys, the smell of dehydrating dog turds in the cause of dog nutrition studies, the returning dogs from the lost Dion Party and their untold story of the actual events, and the final evacuation of Stonington with four teams pulling six sledges one year to the day after the Biscoe had landed us.

Peter Gibbs – Surveyor – Horseshoe 1957; Surveyor/BC – Stonington – 1958

Topographic Survey

Gibbs and Forster

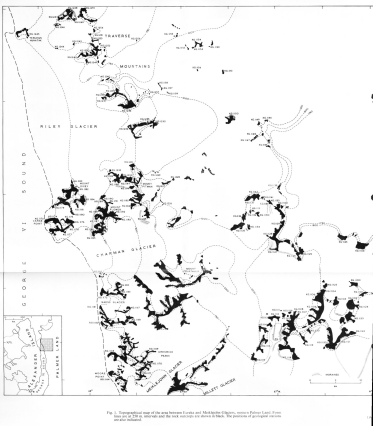

The Stonington base was reopened in March 1958 but no sea ice meant the work was confined to mainland areas accessible from base. Sledge wheel and compass surveys fixed by sun-fixes every 50-60km enable the pair to survey the area between the base south to the Wordie Ice Shelf and across the plateau to Mobiloil Inlet.

In March 1959 severe ice conditions prevented the relief of the base and it was again closed. Fids sledged north to Horseshoe Island where they were picked up by US Navy helicopters.

In January 1959 the first Tellurometers were introduced into the Antarctic at Deception Island, supported by HMS Protector and its helicopters. The MRA1 instruments weighed 60kg and took an hour to warm up and measured the transit time of the measurement. From 1961-71 the MRA2 instruments were fitted with stormproof muffs and an oven and only took only 5-10 minutes to warm up. From 1973 the MRA3 instruments were used which gave a readout of distance in metres.

Autumn Plateau Journey – Peter Gibbs

My first objective that autumn was to find a route ino the Neny trough by which we could return from the planned summer inland journey and carry out survey in the process. Henry and I with the Admirals were supported to the Amphitheatre, the head of the Northeast glacier by Nigel and Bryn with their teams who then continued with Pete and Keith to do some infilling of survey and geology towards Square Bay. The Plateau between the head of the Northeast and Neny trough in autumn is probably most years inhospitable and certainly was so then. The trip achieved its route-finding objective thanks to some memorable breaks in the weather. We named the narrow glacier down which we found a route, the ‘Flaming Peaks’ on account of the tinted summits in the low midday sun.

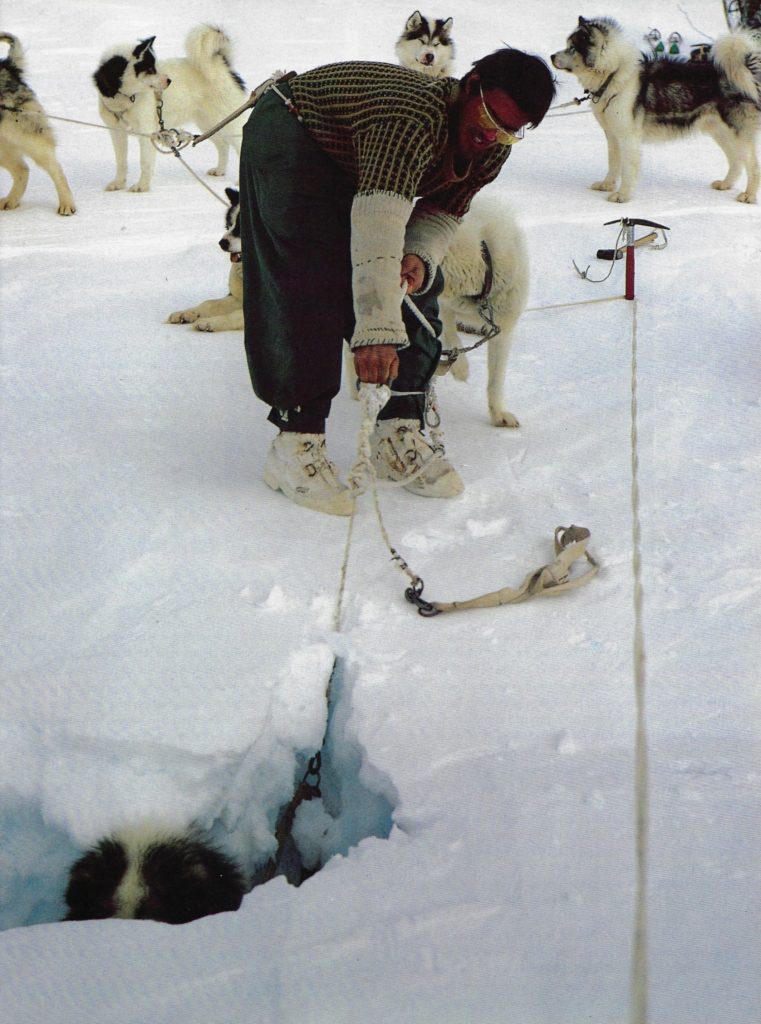

Sea Ice -Peter Forster

The scene is typical of Marguerite Bay in early spring. The old ice, although still many feet thick, begins to break up and to move, due to the wind, tide and movement of the glacier foot. Pressure ridges rise up in fantastic shapes and provide interesting sledging which the dogs love. Cracks open up and refreeze with black ice, and areas of melt water collect on top. This provides an assault course for gymnastic sledging but without the arch dangers of the crevasse. In this case, with all the dogs on the other side, it was necessary to nose the sledge to the ice edge and get the dogs to jerk it across.

Peter Forster, Surveyor, Stonington – 1958, Horseshoe – 1961

Search Journeys – If Dogs Could Talk – Peter Gibbs

We were on the summit anxious to descend (from the Autumn Plateau Journey) but for the final gale which blew from 27th May to 3rd June at force 8 with heavy drift. On the ’68 set we were in contact with Paddy McGowan of Horseshoe island and heard that they had had no contact with their Dion Island party that left on the 27th morning. When the visibility cleared to reveal open water the radio silence sounded deep concern. Geoff Stride, Dave Statham and Stan Black with two 7-dog teams had left Horseshoe island to visit the Dion Islands and collect some specimens requested by Bernard Stonehouse. The ice had been fast I believe over the past 6 weeks during which time it had withstood some gales.

Dog Feed Trials – Peter Gibbs

Our return to Stonington from these search journeys of over 400 miles on the 22nd July heralded the first opportunity to be static on base for a while and give Henry Wyatt an opportunity to do his dog-feed trials. He selected 18 dogs from the Admirals, Spartans and Moomins (survivors from Horseshoe) and left the Churchmen free for Nigel to lay a depot to the Terra Firmas.

We were well aware of the inadequacy of the Nutrican block and I believe a purpose was to investigate the absorption characteristics through analysis of the dehydrated stools. In the cause of science we others tolerated the stink with brave humour but Peter Forster and I preferred to go off on a manhaul trip ostensibly to look for Neny Fjord approaches to the Neny trough as well as to get away from the stink. The story of our fight to save the tent (and us) over a 3-day force ten storm on Postillion Rock is another story as we did not have dogs. I am glad they were spared it as there was no snow left on the rock.

Peter Gibbs – Surveyor – Horseshoe 1957; Surveyor/BC – Stonington – 1958

Spring and Summer Journeys – Peter Gibbs

These were days without air support so in order to support a geology journey south of Cape Jeremy and survey journey from the southern end of the Wordie Ice Shelf and back via the Northeast Glacier, we made several quick trips down to the Terra Firma islands. It was my view that sledge weights should never exceed 850 lbs for efficient travel. Often on sea-ice there was a breakable crust. A lighter sledge made all the difference for progress.

But at the same time for 60 days in the field the minimum dog food weighed 540 Ibs for one 9-dog team. For the summer survey journey, thanks to the brilliance of Caesar as a lead dog, we adopted the most economical sledging outfit having 3 sledges to 3 men with one 3-man tent and a pup tent, thus spreading the fixed weight of 437 Ibs (survey gear, radio, tent shovels, ice axes, ropes etc.).

In addition Pete and I sledged a depot of 2-weeks supplies down to the Wordie Ice Shelf, so that from there we could start with 8 weeks supplies. The addition of the Moomins from Horseshoe was now of great help and Pete drove this team.

Of War And Peace (The Dog Fight) – Peter Forster

In 1961, after 10 years, the base reopened as the centre for fieldwork in the southern Antarctic Peninsula, when Horseshoe Island (Base Y) was closed, and continued until the Base finally closed in February 1975.

The Antarctic huskies appeared to fight at every opportunity. Particularly, after a long period of separations on the spans at base, it seemed necessary that they re- established a pecking order in the traditional manner. Perhaps, the parallel of the Arctic wolf has some relevance in as far as the wolf pack are free to iron out their differences as they arise and can maintain a working hierarchy appropriate for the job in hand – survival, in contrast the spanned husky can harbour the residual grudges of a previous encounter. The start of a sledge journey provided a golden opportunity to state their differences if not to settle them.

Picture this scene – Read on….

Evacuation of Stonington – Peter Gibbs

Like our return from the Autumn journey this one was also overshadowed by the prospect of having to pack all we could and leave Stonington by sledge. On the 4th January, 1959 in contrast to the previous year there was no sign of any ice break-up and snow was accumulating on the island. The ice was fast over Marguerite Bay to the Avian isle as far as we could see. SecFids was in touch with the US icebreaker, the Nadir, in early January and put us on alert to sledge up to Horseshoe. However this remained unconfirmed so we were able to spend the rest of January and February on reports and survey compilation. On the 10th February I noted that the minimum temperature had been +1F and contrasted this with +20F for the same date in 1950, the stars were visible again and the ice as fast as ever without any melt pools. On the 15th a gale left a drift up to the roof of the hut and there was 8 feet of snow and ice depth on the beach where Bryn dug out the 12′ dinghy. An ice cap was forming over Stonington.

Extracted with his Kind Permission from Cliff Pearce’s book “The Silent Sound”

Cliff Pearce:

My own arrival at Stonington was by way of the Muskeg. The trip was exhilarating as the Muskeg trundled over the thick sea-ice, passing to the south of Neny Island, before making a run northwards to the base. The loaded sledges, each capable of carrying two tons of stores, slid easily over the ice as the wide tracks of the vehicle sped along. When we reached the tide crack, the loose ice creaked unwillingly, and the Muskeg hauled its cargo rapidly up the slope towards the growing pile of equipment, building materials and other stores.

Under a rapidly encroaching snow drift, I found the door and entered. In the small habitable portion of the hut, Peter Forster and Peter Grimley had already prepared a welcome brew of tea. They, with Charlie LeFeuvre and Dr. Tony Davies, had been flown into Horseshoe Island in March of 1960. After wintering at the more comfortable base to the north, in August they had sledged down to Stonington Island, from where their field work could be centered. During the part of the year that was left to them, they had ben able to carry out considerable geology and survey work on the eastern flank of Graham Land. S the summer advanced, and the ship drew near, they spent more time at the base, or what remained of it. The thirtenn-year old hut was in a poor state of repair. During the years when it had been unoccupied, snow and ice had filled the majority of the rooms. However, one small room had been triumphantly reclaimed, in which the four men had lived, almost on top of one another. It was in this room that we sipped tea, and had a meal cooked from the last remnants of food taken in when the base had last been relieved in March of 1958.

Topographic Survey

Forster – (Stonington Island and Horseshoe Island)

Heavy sea ice prevented access to Stonington but in Feb 1960 a party of 4 was flown into Horseshoe Island. Peter Forster mapped areas of Bourgeois Fjord and Square Bay not covered by air photography. The party then moved south to Stonington. Exploratory surveys were carried out between 68.5s and 69.5s the survey linked to work by BGLE 1936 and down the Lurabee Glacier to work by Mason 1947

1961

Base Commander – Johnny Cunningham

| Bowler, B.A. (Bryan) | Tractor Mechanic |

| Chapman, H.E. (Howard) | Surveyor |

| Cunningham, J.C. (Johnny) | BL |

| Fraser, A.G. (Arthur) | Geologist |

| Matthews, R.P. (Roger) | Meteorologist |

| Metcalfe, R.J. (Bob) | Surveyor |

| Quinn, J.A. (Tony) | Radio Operator |

| Sparke, B.R. (Brian) | Medical Officer |

| Tracy, W.O. (Bill) | GA |

| Tween, M.H. (Mike) | DEM |

| Wigglesworth, J.B. (Brian) | Meteorologist |

Topographic Survey

Chapman and Metcalfe

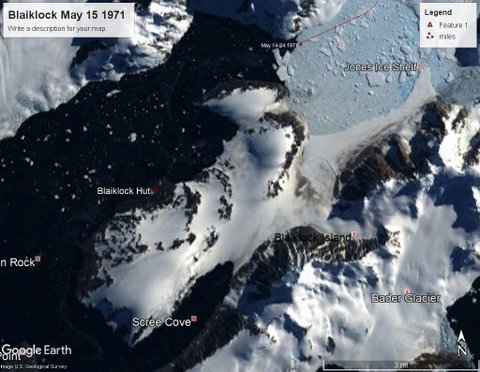

In Aug 61 Howard Chapman and Bob Metcalfe set of from Stonington in two Muskeg tractors to travel across the sea ice and south down King George VI Sound to Fossil Bluff. One Muskeg was lost at sea and with the aid of dogs 5 traverse stations were recced south of Fossil Bluff but meltwater on the Sound stopped work in January and the surveyors were withdrawn by air. In March 62 Metcalfe flew back to Fossil Bluff to observe a 16 star astro-fix.

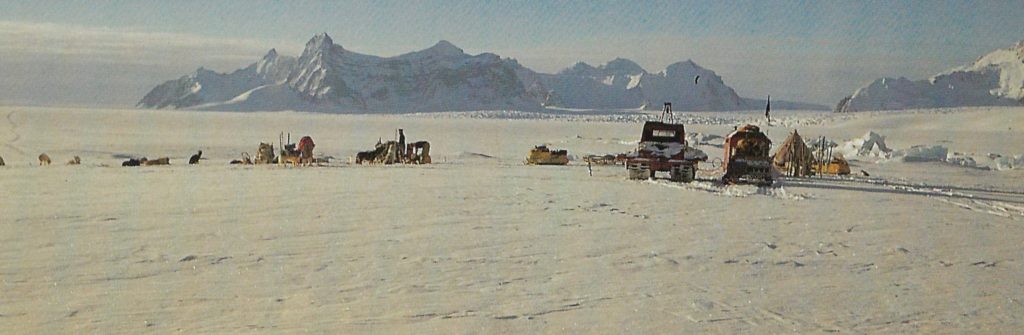

August 23rd – From Stonington to Fossil Bluff – Dog Teams and Muskegs (as seen from Fossil Bluff)

(Extracted from Cliff Pearce’s book “the Silent Sound”)

The prime objective of establishing Fossil Bluff as a forward base was that it should make possible geological and survey work on Alexander Island and eventually in areas further afield. It was therefore of paramount importance that men and materials and equipment should get to Fossil Bluff as early as possible, preferably during September or October, when at least three or four months of field work could be carried out.

John Cunningham, Base Leader, was an outstanding mountaineer who had climbed extensively in the Himalayas and elsewhere. He was serving the second of three consecutive years down south, all as base leader, the first at Port Lockroy, the latter two at Stonington Island. (Later still, in 1964 he returned to Adelaide Island and led the first ascent of Mount Andrew Jackson, the highest mountain in Graham Land at over 11,700 feet.)

Mike Tween and Tony Quinn spent almost the entire year at the base, apart from short local trips, in order to provide power and to maintain radio communications with other bases and with the various Read on…..

1962

Base Commander – Johnny Cunningham

| Bowler, B.A. (Bryan) | Tractor Mechanic |

| Clennell, J.J.O. (Jon) | GA |

| Cunningham, J.C. (Johnny) | BL |

| Gilchrist, W. (William) | Radio Operator |

| Gill, R.V. (Ron) | Tractor Mechanic |

| Hodges, B.A. (Ben) | GA |

| McMorrin, I. (Ian) | GA |

| Metcalfe, R.J. (Bob) | Surveyor |

| Morgan, I.P. (Ivor) | Surveyor |

| Wilson, J.M. (Jim) | DEM |

Topographic Survey

Metcalfe and Morgan

In August 1962 Bob Metcalfe and Howard Morgan mapped the area between North East Glacier and Square Bay.

In October Metcalfe and Morgan were flown from Stonington south to Fossil Bluff, travelling by muskeg and dog sledge and with air support 13 new stations were established and 15 lines measured extending from Fossil Bluff to Buttress Nunataks.

1963

Base Commander – Jon Clenell

| Beynon, A.D.G. (David) | Dentist |

| Blake, S.C.B. (Sam) | Radio Operator |

| Clennell, J.J.O. (Jon) | BL, GA |

| Fleet, M. (Mike) | Geologist |

| Hodges, B.A. (Ben) | GA |

| Horne, R.R. (Ralph) | Geologist |

| Kennett, P. (Peter) | Geologist |

| Marsh, A.F. (Tony) | Geologist |

| McLeod, G.K. (George) | GA |

| McMorrin, I. (Ian) | GA |

| Tindal, R. (Ron) | GA |

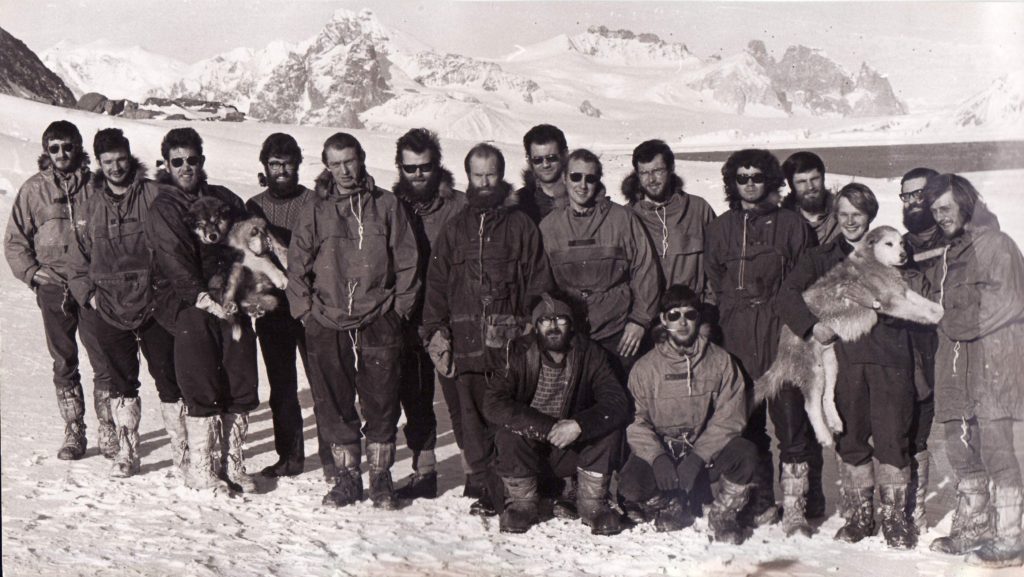

Front row Left to Right: Dick Palmer; Mike Fleet (green anorak); Tony Marsh (in pink); Ben Hodges (squatting); George McLeod, also squatting). Temp that day was Minus 35.5 F!

(Photo: Peter Kennett)

Dogs In Rough Ice – George McLeod

Prancing Pup

One story I have is waking up and seeing in the distance one of my pups up amongst the crevasses, so nipping out of bed I called him back, but he just pranced around and stayed where he was. Putting skis on, I skied up thinking he’s scared of the holes. I got there to find one of his brothers in a crevasse and he would not leave him. After a rope rescue, we brought both pups down to their great delight. They were such good friends, we ran them together when they got older.

Three men, two sledges and 250 miles to go

The temp was 37 deg F. Snow had turned to slush and we had to get home. In three days we ran 153 miles, through inches of water on the ice. The dogs were soaking wet and miserable, so bad in fact, they wouldn’t even fight.

When we reached Prince Gustav Channel it was all buckled ice and water to three feet deep. The dogs were wonderful, none of them balked. With me in the lead, crampons and ice axe and tied into the dog-trace, I’d sometimes be into my chest pulling, and the dogs would all swim to the solid ice beyond. We did this for two days, until forced ashore, the ice ahead had broken up and we could see water shadow on the icebergs up the Channel. You’d better believe I was good to my dogs after that.

(Written by George while at Hope Bay)

A Terrible Beating

John, Ben Hodges and I were sitting at the base of Sodomy Slope (Sodabread), in a screaming blizzard, with 3 dog teams, safely dug into the snow, we hoped. Ben and I with everything on and roped to John inside the tent, we crawled out to feed the dogs. God! What a mess, dead dogs on top of hard packed snow, most dogs buried underneath. If we dug them out they would freeze and if we left them under they would die.

Ben loved his dogs and took the time to bury two of his next to a rock buttress, while John and I downed tent, dug out our dogs and tottered back to Base.

It took us a day’s work to remove all the snow from inside the coats of the dogs. I’d never seen that before. The snow was packed inside the dogs thick coat, right to the skin and one had to push fingers right inside to get the snow out. You know how a husky’s tail curls, well, their tails hung straight down, solid with snow.

Ben lost two dogs, and John one. We took a terrible beating, yet in a couple of days, the dogs were back, bright eyed and bushy tailed.

Scrummaging Dogs and Sea-ice – George McLeod

Three of us and three teams had been out of base for several days on bad sea ice. It was short]y after the lads from Horseshoe Island had gone missing, and we were all a bit nervous. Well, it happened. Ken and his team broke through into the water. We managed to drag him and the dogs out but it took us two hours, running all the way, before we reached firmer ice and were able to stop. By that time Ken’s legs and feet had really frozen up and he was in a bad way. The tent erected, we thawed him out and he immediately lost the skin off both legs and feet. In our haste we had just picketed the dogs, and all of a sudden we heart a big fight erupting outside.

A couple of us rushed outside and found the 30 dogs had pulled the pickets and were all scrummaging down. Once we got them sorted out, we found “Ruthie’s” stomach so torn that her insides were hanging out. I pushed everything back in, roughly stitched her up and got ready to head home.That was a hell of a journey, still on poor sea ice and with three days back to base. I led out front with two dog teams (18 dogs), two sledges, two men – Ken could just about walk – and then Ruthie following the sorry caravan procession behind me.

That night when we pitched camp, there was no sign of Ruthie. Ken was in agony and none of us could sleep. Suddenly the dogs began barking. I jumped out of my sleeping bag to investigate. It was Ruthie. dragging herself into camp. I thought I ought to put her out of her misery. But no, she’d made it this far, blood loss and all. We got back to base two days later and it took Ruthie almost another full day – but she made it. In time her belly healed and she was back to work as if nothing had happened.

George McLeod, Stonington, 1963; Adelaide and Fossil Bluff, 1965/68

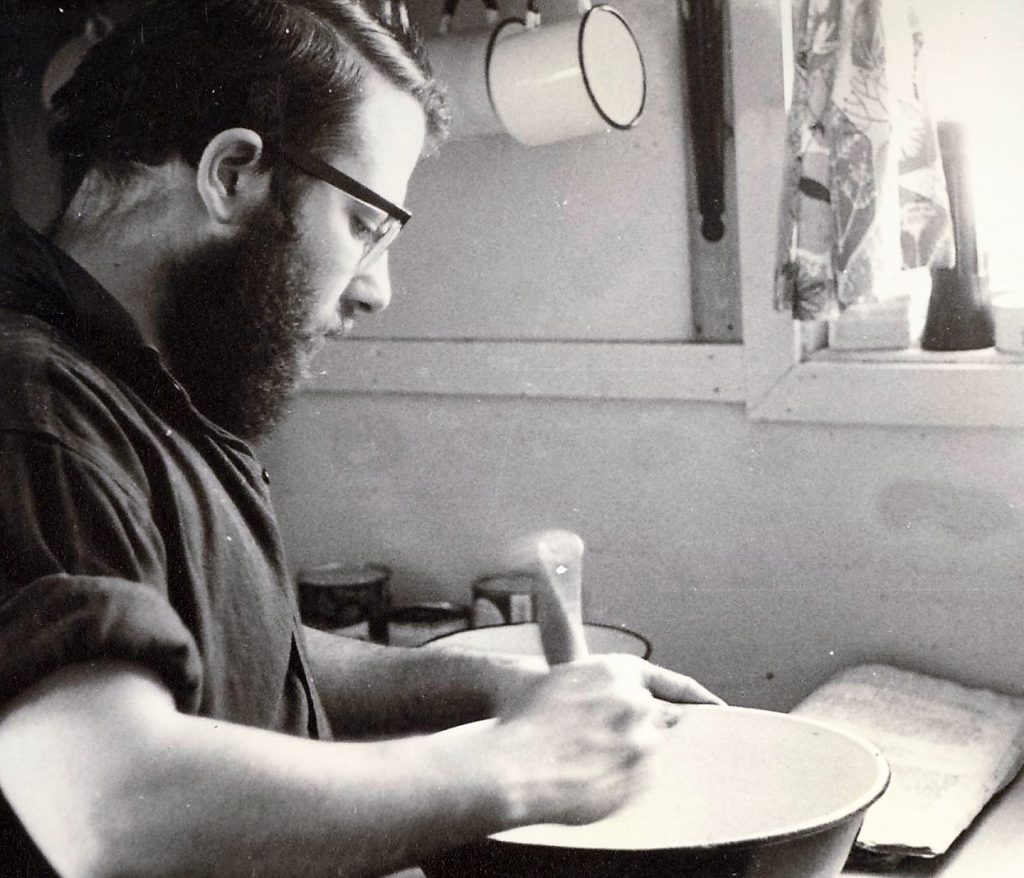

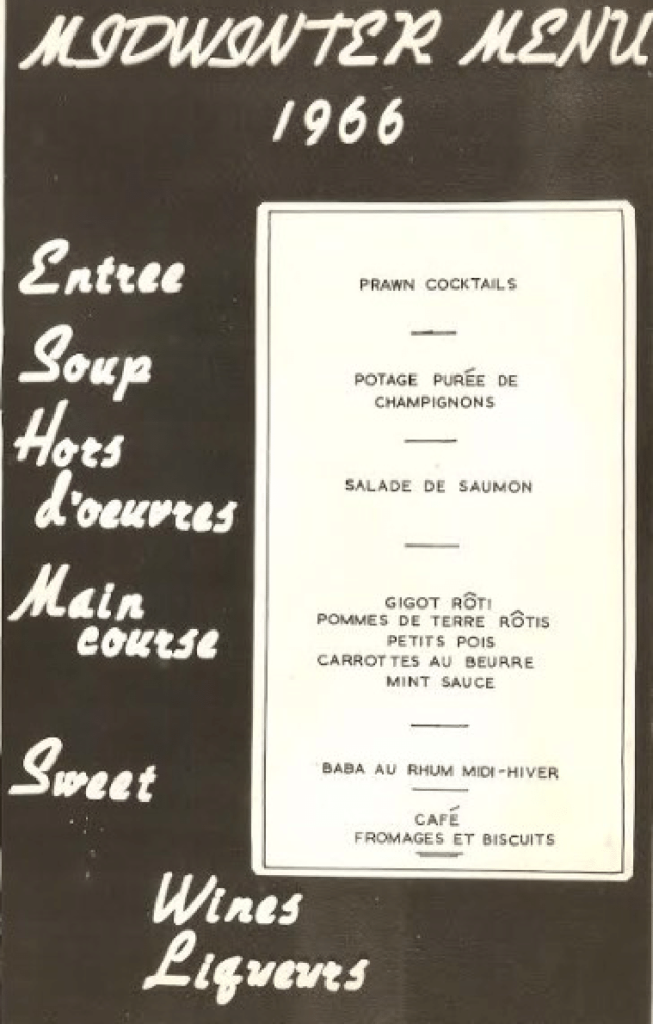

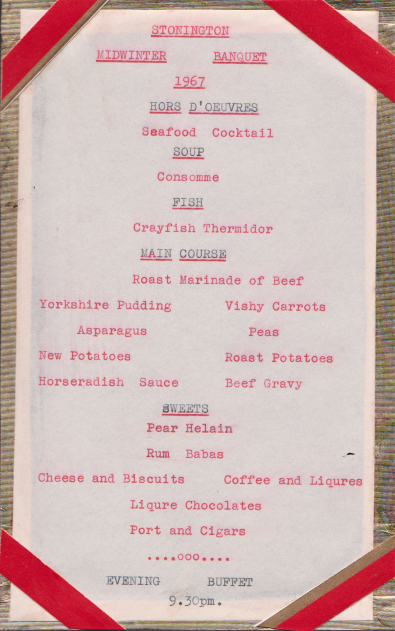

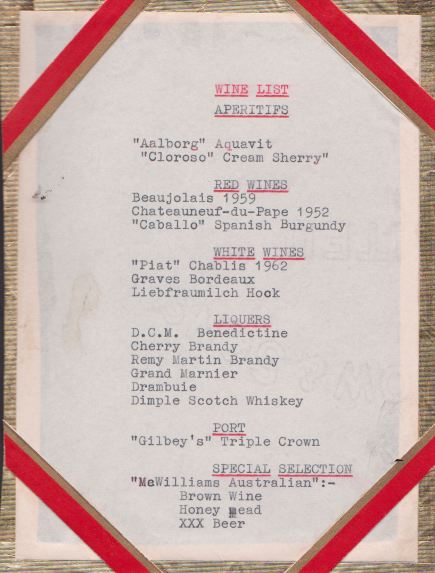

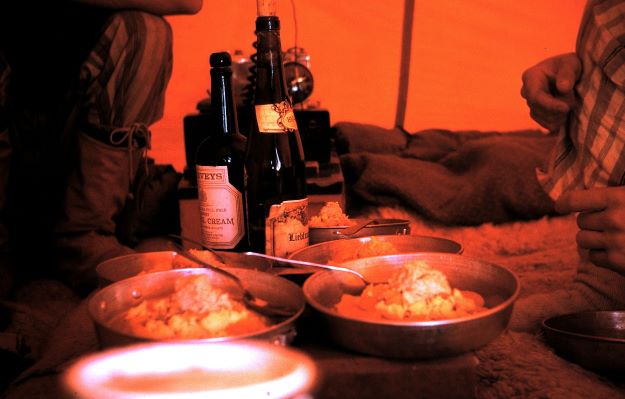

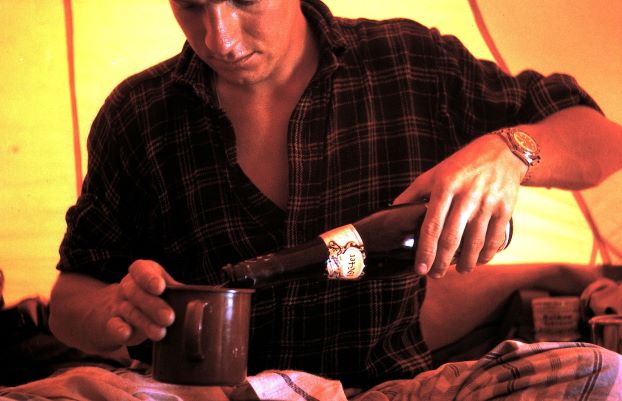

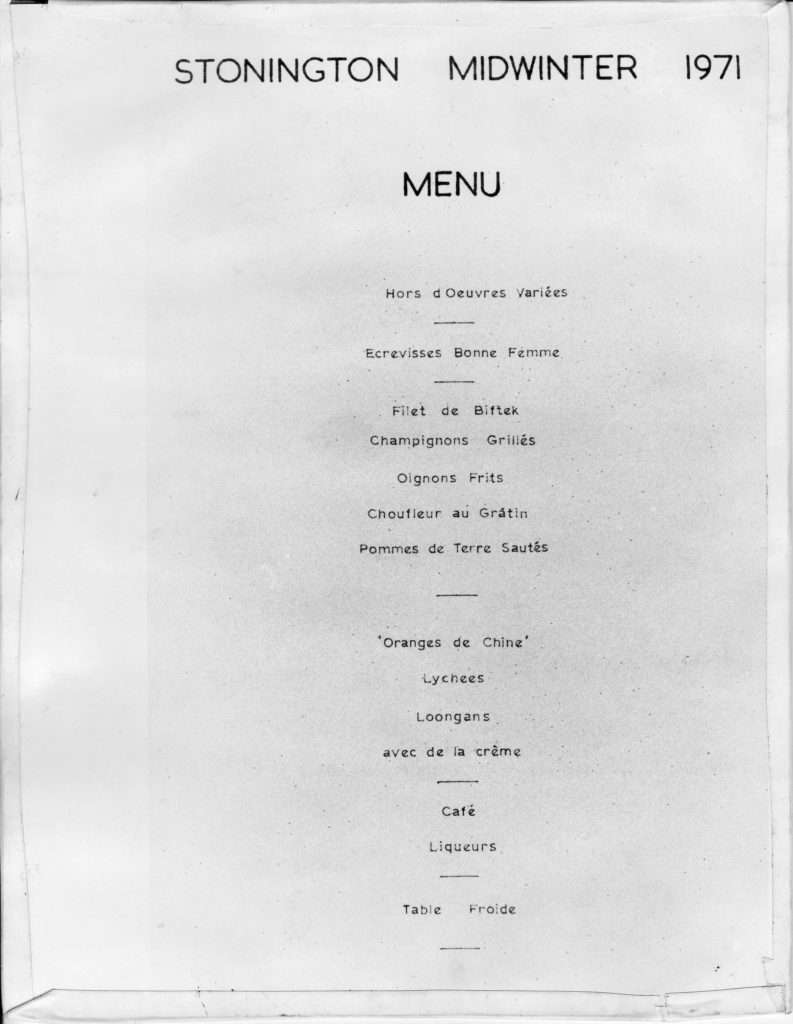

Culinary arts at Stonington – Peter Kennett

The ways in which most bases organised their cooking will be familiar to old Fids, but it might be of interest to the younger generation to know how we coped at Stonington in the 1960s, which was probably typical. Like most bases, we had no professional cook, but took it in turns to provide for the members, numbering up to 12 when nobody was out sledging. Our method was for the cook to serve a three day stint.

Having largely had my food provided for in my student days, my only experience of cooking was at Scout camps, where one could often get away with murder! Catering for 11 others, from whom one could not escape if things went wrong, was rather different. Some cooks were so well organised that they could relax in between meal times or carry out other jobs, but for me it became almost a full time occupation for those three days, even allowing for the help of the “gash hand” rota, where there was always somebody else to top up the melt tank with snow blocks, bring in more anthracite for the Esse stove and assist with washing up.

Night Noise on the Spans

Ralph and I were up on Uranus Glacier, a hundred miles or so from the sea. It’s night time and everyone has settled down, when there’s a curious little bark from Signy my lead dog. I said “It’s just the dogs messing around”. I went outside to find a penguin peering at the dogs. I turned Signy loose and she quickly caught and killed the penguin, which Ralph and I cooked and ate, whilst Signy enjoyed what was left. A curious little tale, because what’s a penguin doing up at 1,000 feet anyway?

George McLeod – GA/BC – N (Anvers Island) 1957; J (Prospect Point) 1958; D (Hope Bay) 1962; and E (Stonington) 1963 and 1967

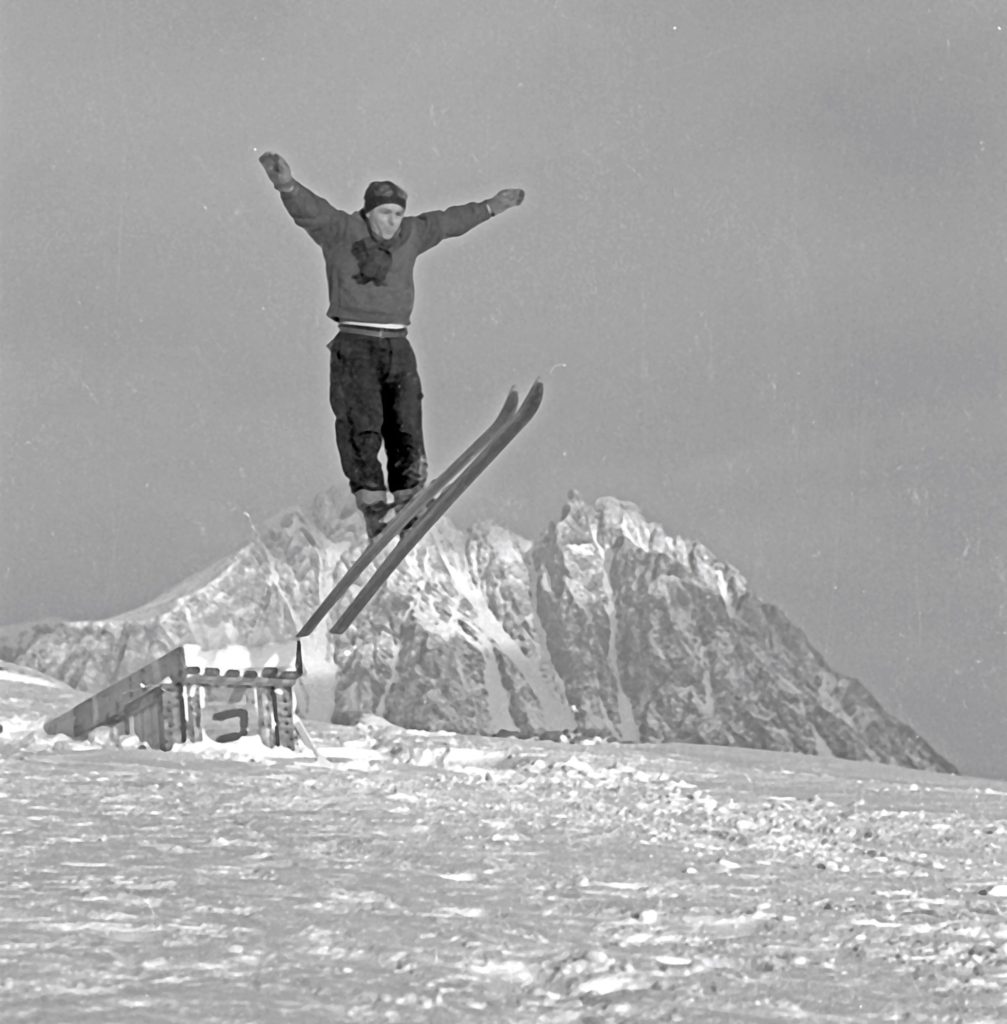

The Ski Slope – Mike Fleet

Skiing on Stonington Island was very limited. With a maximum elevation of 25m (Anemometer Hill) and only some of this height was available for skiing. So skiing was very limited, but it was just outside our back door and popular. The alternative was a long trudge up Northeast Glacier.

Eliasoneering – in theory and in practice! – Peter Kennett

Photographs are by Peter Kennett, unless otherwise stated, or unless inadvertently mixed up with the communal photographic processing on base!

The current generation of Fids (2020), accustomed to whizzing about effortlessly on Skidoos or quad bikes, may not be aware of the trials and tribulations endured by those of us in the 1960s, faced with the introduction of the first mechanical transport by BAS. If memory serves correctly, there was a choice of small motor sledges between an early version of the Skidoo and the Eliason. For some reason, the powers-that-be decided to buy the Eliason, and several were sent to Marguerite Bay, with two of them (Nos: 2000 and 2001) destined for Base E at Stonington Island, as was I.

When the changeover of personnel took place at Stonington, in late February 1963, the usual responsibilities for different areas of base life were allocated. Having once helped John Mansfield (Hope Bay 1963/4), strip and reassemble a 1932 MG car, and then having maintained a 1949 Singer 10 saloon myself, I was optimistically regarded as being a mechanic, and was therefore assigned the job of looking after the Eliasons. Thanks initially to considerable help from Ron Tindal, and later, professional expertise from Dick Palmer, we were able to keep the machines running for much of the season, but not before much sweat, tears and even a bit of blood had been shed.

The Eliason consisted of a steel frame, powered by a 4-stroke Briggs and Stratton lawn mower engine, which drove a track belt consisting of steel lugs attached to a pair of motor bike chains.

See more of Peter’s photos around Stonington HERE

See some more of Peter’s photos around Stonington HERE

The Depot Journey to Three-Slice Nunatak – Mike Fleet

Click below to Start Mike’s Gripshow:

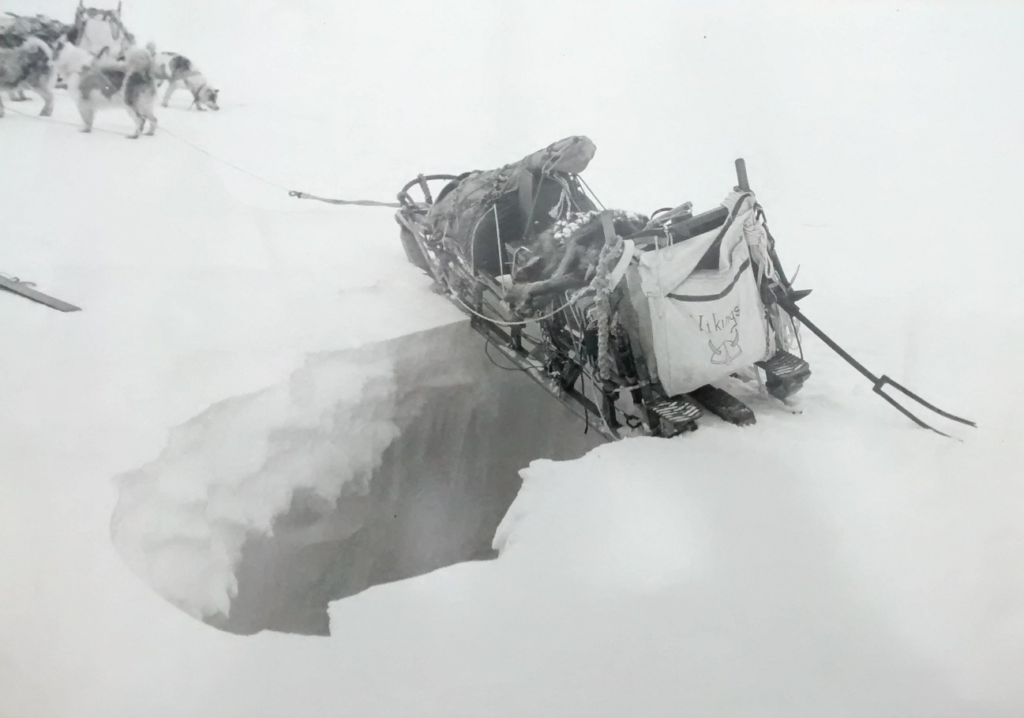

Sodabread Crevasses – Ben Hodges

We were nearing the end of a four-month, 1,000-mile sledge trip, and one final hurdle awaited us — the terrifying 5,000 foot descent of “Sodabread”. Though the ascent had taken us ten long days at the beginning of the trip, the descent would, in theory, take only half an hour. Visibility was poor that day and Mike Fleet, myself and the two other teams took a break to discuss the whereabouts of the survey pole we had left to mark the only safe route down.

(Photo: Peter Kennett)

We finally agreed on the direction and I called “Pull away, dogs!” My team, the Moomins, surged forward, out of my control, and for a moment I feared that we might plunge over the glacier; then I realised that the lead dog had spotted the survey pole: she was heading for home. A long drawn out “Aaahh now” brought them under control and we came to a halt at the top of the descent.

Controlling our rate of descent was a major problem and we wrapped as many chains and ropes as we could around the sledge runners to try to prevent them front over-running the dogs. I put “Harvey” and “Eccles”, the strongest and slowest dogs, on a long trace and fastened them to each side of the sledge to provide extra braking power. With a cry of “Up Dogs! Huit!” my team and I began the terrifying descent, the two other teams following behind at five-minute intervals. The rushing nightmare lasted for two long minutes before the brakes took any noticeable effect and we began to slow down.

We had nearly reached the end of the traverse when “Dot”, my lead dog, quite suddenly vanished. The pair behind her also disappeared, and it was then I saw the faint line of the crevasse. The other three pairs of dogs dropped from view in quick succession.

Handing over Dog Teams

When the time came, handing over a team to an incoming new driver (and sometimes a driver who had previously driven a team) was an emotional affair. Most Fids were sick at the thought of leaving their team at all, most of all to a stranger who surely would not understand them; and so they tried to give the new driver some ideas, in the form of a Team Report – a set of notes on the dogs, and how they had been driven for the last year or two, while in many cases, being utterly convinced that the new driver would never be able to handle or understand the team properly. There are several other Team Reports on this website (Noel Downham – The Terrors – E-1964, Neil Marsden – The Komats – E-1966).

Here’s the first one:

The Spartans – March 1962 to March 1964 – Ian McMorrin

The Spartans comprised:

3 Dogs born at Horseshoe (Epsilon, Nu, Iota),

2 Dogs from Hope Bay (Steve and Ruth),

2 from Deception (Olaf and Sven),

2 from Stonington (Athos and Angus),

2 from Adelaide (Faerie and Brownie)

General Notes – 1962/63 Season

I took over the Spartans from J.B.Wigglesworth in March 1962 by which time they comprised, Epsilon, Steve, Iota and Nu. The strength of the team had been greatly reduced by the loss of Vicar, Moose and Tess during the 1961/62 summer season. This deficiency in power was partly made up by the addition of Athos and Faerie though the overall strength of the team still remained fairly low.

A simple way to get to Stonington – Sandy Muir

December 1963! This is the tale of two medical officers’ trip to Marguerite Bay. Mike Rice was going to Adelaide base and I was to go to Stonington. We had been delayed by our research preparations in the MRC unit and were therefore to ship south in a somewhat complicated way. The plan was for us to sail south on a chartered Danish ship, the Kista Dan, which was doing the trip to Halley Bay. We were to meet up with the John Biscoe in South Georgia which was scheduled to relieve Adelaide and Stonington. It did not go quite to plan.

Mike and I were just settling in and meeting up with the Fidlets going to Halley Bay when we added another late-comer to our trip. It was Garrick Grikurov a Russian Geologist who was going to see how our geologists worked and had been assigned to Stonington. Russian!! This was 1963 and joint working with the Soviets just did not happen! However Garrick was a great chap to have around and he had a great sense of humour and provided us with a valuable insight of life in the USSR.

1964

Base Commander – Noel Downham

| Cheek, J.E. (John) | Radio Operator |

| Downham, N.Y. (Noel) | BL |

| Grikurov, G.E. (Garrick) | Geologist |

| Marsh, A.F. (Tony) | Geologist |

| Muir, A.L. (Sandy) | Medical Officer |

| Renner, R.G.B. (Geoff) | Geophysicist |

| Schärer, A.J. (Tony) | GA |

| Steen, J.W. (Jim) | GA |

| Stubbs, G.M. (Guy) | Geologist |

| Thornton, E. (Edwin) | GA |

| Vaughan, D.N. (David) | Tractor Mechanic |

“Man Meets Dog” – Noel Downham

On one trip we took along a book called “Man Meets Dog” by Konrad Lorentz, the animal behaviourist. One of his suggestions for keeping dogs in line was to mimic the bullying actions of the big dogs. It sounded logical enough and the dogs being an unruly bunch, I was anxious to put it into practice. I watched them for a while and noticed how the big dogs took hold of the smaller ones by the ears and shook them. It seemed to work effectively enough, so I tried it out on “Princess”. Never again!

(Photo: Geoff Renner)

Remembering too late that dogs are copraphagic – they eat each other’s faeces I came away with a mouthful. It would appear that “Jet” had earlier had a snack around Princess’s rear end, before trotting round to the front to indulge in a bit of courting. Re-cycled Nutrican isn’t tasty and I don’t recommend it.

Noel Downham – Met. Admiralty Bay – 1960; GA – Hope Bay – 1961 & 1963; GA/BC – Stonington – 1964

“Flush” – Geoff Renner

(Photo: Geoff Renner)

Had she been a horse her coat might have been defined as mealy bay or skewbald. As an Antarctic husky bitch she was favourably described as “golden tan on white”, less literally as “ginger”. That her colouring was unusual was as unsurprising as she was exceptional. In 1964 she celebrated her seventh birthday, scaled in at a sledging weight of 78 lbs and moved her residence. Her name was “Flush”, though because of an engaging arrogance she was also known as “The Duchess”.

Flush had been raised at Hope Bay, a FIDS base bred with sledging legends. Field trips out of there, whether reconnaissance, survey or scientific discipline epitomised the early days of oversnow travelling. Theirs was a heroic period but because of strategic and logistic reasons Hope Bay was scheduled for closure in 1964. An era had come to an end and with it the inevitable disbandment of the dog unit. However, five hundred miles to the South lay Marguerite Bay where a new order of field travel was establishing. Where better to relocate the dog teams?

Sledging Notes & Tales – Noel Downham

Biographical Notes

On a strictly personal basis my dog sledging history started at Admiralty Bay (King George Island). After a three weeks training trip, 3 of us started on a six-month geological trip. The weather was atrocious, but our desperate inexperience did not help much as a lot of our time was spent ‘lying up’ on the Island’s Plateau. So often we had to wait for visibility to lift so that we could find the ridges down to the outcrops.

There had been 2 fatalities directly attributable to running in front of the dogs and, in general, poor team discipline, so much time was subsequently spent in training. The dog discipline was excellent.

I then went to Hope Bay in 1961 and took over the Terrors from Neil Orr who had started the team. Hope Bay, in the previous two years, seeing the folly of running in front of dogs, had been developing far better lead dogs and team discipline.

Ian Fothergill was BL. that year and had two geologists, 2 surveyors, 1 geophysicist and often, with one or two depot-laying parties thrown in, we would have 7 sledge parties in the field at once.

Brevity in sledge reports became the cool and intrepid thing to write and so there was limited passing on of information. This in hindsight was stupid, considering some very impressive trips that were made. And this could have been of great help to later parties.

Effectively from the late 1950’s to the closure of Hope Bay in early 1964 the Trinity Peninsula was thoroughly mapped, geologised, gravity and magnetically surveyed from the northern tip down to Jason Peninsula and the dogs were our sole means of transport. South of Jason the work was continued from Stonington.

In the summer of 1963/64 I took the bulk of the Hope Bay dogs to Marguerite Bay, though two teams went to Halley. The ones that went to Stonington were fit, hardened and very well trained which was imperative for taking the 5 ton loads over The Amphitheatre, Sodabread and Bill‘s Gulch and down to the East coast. The East coast project then tied up many geological loose ends and the dogs were our sole means of travel and depot-laying with minimal use of an air-laid depot at 3-Slice Nunatak and another at Cape Robinson.

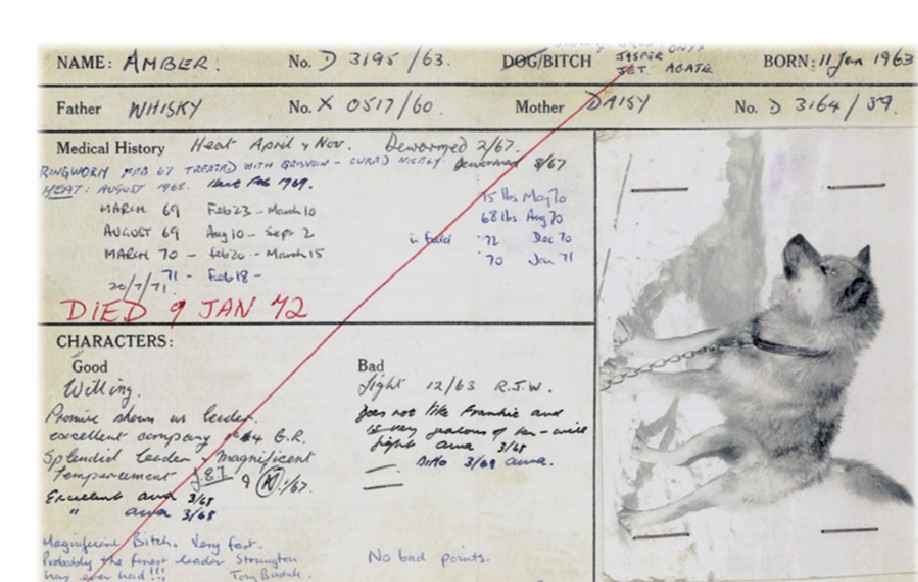

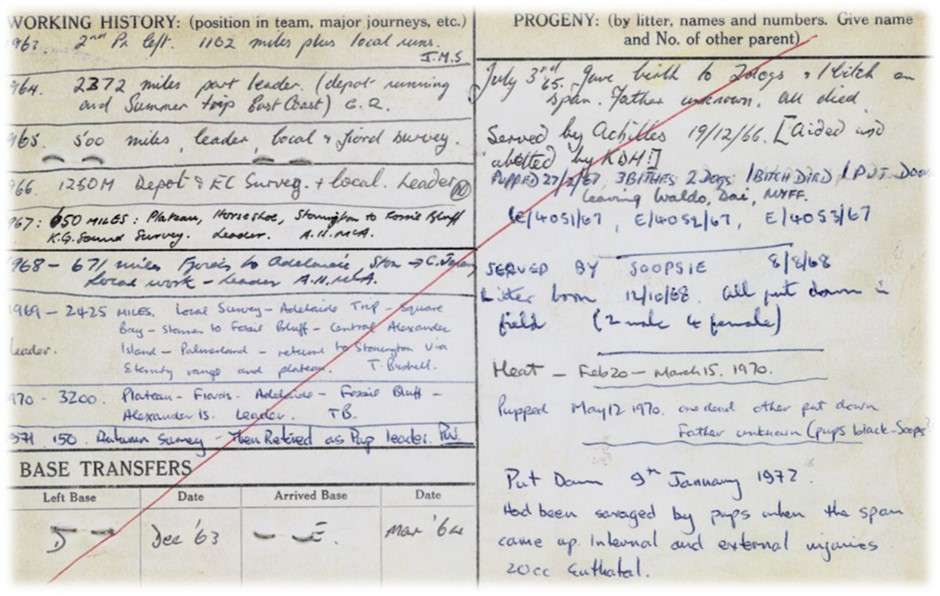

Amber and the Komats – Geoff Renner

Amber could not have long been in the Komats when I took over in mid-1964 at Stonington. Her previous driver was John Cheek at Hope Bay. John was the radio-operator at Stonington in 1964 having come down from Hope Bay with Noel Downham. It was warming to see Tony B’s comments regarding Amber “Magnificent Bitch. Very fast. Probably the finest leader Stonington has ever had”.

(Photo: Geoff Renner)

(Photo: Geoff Renner)

Geoff Renner, Geophysicist, Stonington 1964

More Tales – Noel Downham

Two of us were sledging off the Jason Peninsula with two teams. Because of the pending ship survey we were ordered to get back to base immediately. There was a steady wind and ground drift blowing off the plateau and l was the second team. We were heading north and my partner‘s team kept veering to, the east, away from the wind. The wind was so strong that he was having great difficulty using his whip to get them back on course. Then in desperation he stopped, tied the end of the whip onto the handlebars of the sledge and started hurling the heavy handle to leeward to try and get the team to turn up wind.

From my viewpoint the vision of a bloody great whip handle, (we were still using the 40 ft. Bingham style whips) hurtling through the air and the string of unrepeatable expletives that followed it made my day.

We were sledging off Cape Lachman on the Gustav Channel side of James Ross Island. It was an area where seals often congregated and sun-bathed. There were inevitably many seal breathing holes and you can imagine the pandemonium when a seal shot right up in the middle of my team, smack hang in the middle of the centre trace.

Drama and Death in Bill’s Gulch – Geoff Renner

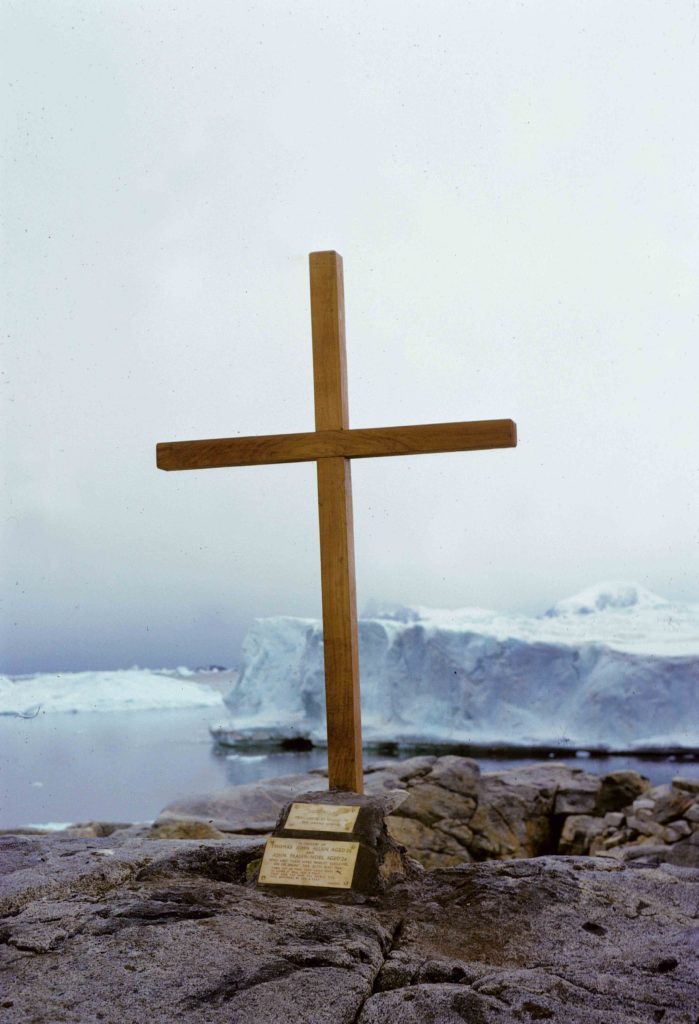

The Terrors and the Komats shared much. They had originated at Hope Bay, trained and travelled many miles in one another’s company, moved to Stonington by ship then returned oversnow to Hope Bay. They also shared a family – a litter of five ‘semi-precious stones’. Whilst Amber, Jasper and Agate ran with the Komats, Jade and her brother Onyx pulled with the Terrors. Cain was a leader of the Terrors backed by the centre-trace pairings of Jade and Nick, Kelly and Jet, Onyx and Bryn, then nearest the ‘cowcatcher’ the powerhouse duo of Mac and Coll. Where Coll lacked in IQ he made up for in grit and spirit. He was also one of the first Antarctic huskies to undergo major surgery. This was to remove a seal bone critically lodged in his intestine. The operation was successfully completed during his sea passage from Hope Bay to Stonington Island in early February 1964 – on board the RRS John Biscoe. Unfortunately, Jade was never able to realise her full potential as a sledge dog for she was killed in a harrowing accident during her maiden journey out of Stonington Island.